Legends of the Lost

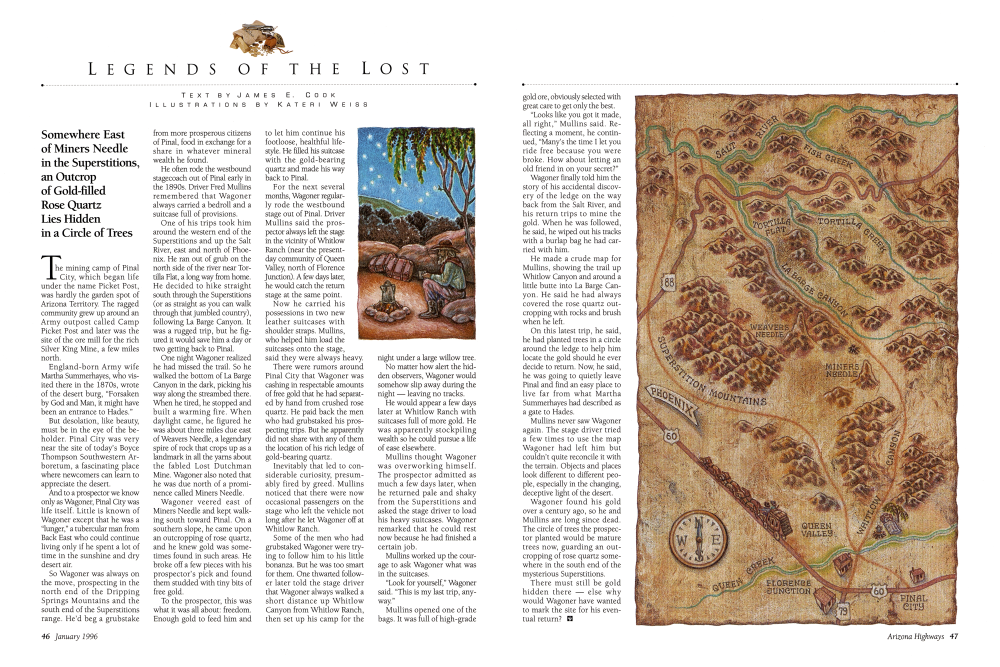

LEGENDS OF THE LOST Somewhere East of Miners Needle in the Superstitions, an Outcrop of Gold-filled Rose Quartz Lies Hidden in a Circle of Trees

The mining camp of Pinal City, which began life under the name Picket Post, was hardly the garden spot of Arizona Territory. The ragged community grew up around an Army outpost called Camp Picket Post and later was the site of the ore mill for the rich Silver King Mine, a few miles north.

England-born Army wife Martha Summerhayes, who visited there in the 1870s, wrote of the desert burg, "Forsaken by God and Man, it might have been an entrance to Hades."

But desolation, like beauty, must be in the eye of the beholder. Pinal City was very near the site of today's Boyce Thompson Southwestern Arboretum, a fascinating place where newcomers can learn to appreciate the desert.

And to a prospector we know only as Wagoner, Pinal City was life itself. Little is known of Wagoner except that he was a "lunger," a tubercular man from Back East who could continue living only if he spent a lot of time in the sunshine and dry desert air.

So Wagoner was always on the move, prospecting in the north end of the Dripping Springs Mountains and the south end of the Superstitions range. He'd beg a grubstake From more prosperous citizens of Pinal, food in exchange for a share in whatever mineral wealth he found.

He often rode the westbound stagecoach out of Pinal early in the 1890s. Driver Fred Mullins remembered that Wagoner always carried a bedroll and a suitcase full of provisions.

One of his trips took him around the western end of the Superstitions and up the Salt River, east and north of Phoenix. He ran out of grub on the north side of the river near Tortilla Flat, a long way from home. He decided to hike straight south through the Superstitions (or as straight as you can walk through that jumbled country), following La Barge Canyon. It was a rugged trip, but he figured it would save him a day or two getting back to Pinal.

One night Wagoner realized he had missed the trail. So he walked the bottom of La Barge Canyon in the dark, picking his way along the streambed there. When he tired, he stopped and built a warming fire. When daylight came, he figured he was about three miles due east of Weavers Needle, a legendary spire of rock that crops up as a landmark in all the yarns about the fabled Lost Dutchman Mine. Wagoner also noted that he was due north of a prominence called Miners Needle.

Wagoner veered east of Miners Needle and kept walking south toward Pinal. On a southern slope, he came upon an outcropping of rose quartz, and he knew gold was sometimes found in such areas. He broke off a few pieces with his prospector's pick and found them studded with tiny bits of free gold.

To the prospector, this was what it was all about: freedom. Enough gold to feed him and to let him continue his footloose, healthful lifestyle. He filled his suitcase with the gold-bearing quartz and made his way back to Pinal.

For the next several months, Wagoner regularly rode the westbound stage out of Pinal. Driver Mullins said the prospector always left the stage in the vicinity of Whitlow Ranch (near the presentday community of Queen Valley, north of Florence Junction). A few days later, he would catch the return stage at the same point.

Now he carried his possessions in two new leather suitcases with shoulder straps. Mullins, who helped him load the suitcases onto the stage, said they were always heavy.

There were rumors around Pinal City that Wagoner was cashing in respectable amounts of free gold that he had separated by hand from crushed rose quartz. He paid back the men who had grubstaked his prospecting trips. But he apparently did not share with any of them the location of his rich ledge of gold-bearing quartz.

Inevitably that led to considerable curiosity, presumably fired by greed. Mullins noticed that there were now occasional passengers on the stage who left the vehicle not long after he let Wagoner off at Whitlow Ranch. Some of the men who had grubstaked Wagoner were trying to follow him to his little bonanza. But he was too smart for them. One thwarted follower later told the stage driver that Wagoner always walked a short distance up Whitlow Canyon from Whitlow Ranch, then set up his camp for the night under a large willow tree. No matter how alert the hidden observers, Wagoner would somehow slip away during the night - leaving no tracks.

He would appear a few days later at Whitlow Ranch with suitcases full of more gold. He was apparently stockpiling wealth so he could pursue a life of ease elsewhere.

Mullins thought Wagoner was overworking himself. The prospector admitted as much a few days later, when he returned pale and shaky from the Superstitions and asked the stage driver to load his heavy suitcases. Wagoner remarked that he could rest now because he had finished a certain job.

Mullins worked up the courage to ask Wagoner what was in the suitcases.

"Look for yourself," Wagoner said. "This is my last trip, anyway."

Mullins opened one of the bags. It was full of high-grade gold ore, obviously selected with great care to get only the best.

"Looks like you got it made, all right," Mullins said. Reflecting a moment, he continued, "Many's the time I let you ride free because you were broke. How about letting an old friend in on your secret?"

Wagoner finally told him the story of his accidental discovery of the ledge on the way back from the Salt River, and his return trips to mine the gold. When he was followed, he said, he wiped out his tracks with a burlap bag he had carried with him.

He made a crude map for Mullins, showing the trail up Whitlow Canyon and around a little butte into La Barge Canyon. He said he had always covered the rose quartz outcropping with rocks and brush when he left.

On this latest trip, he said, he had planted trees in a circle around the ledge to help him locate the gold should he ever decide to return. Now, he said, he was going to quietly leave Pinal and find an easy place to live far from what Martha Summerhayes had described as a gate to Hades.

Mullins never saw Wagoner again. The stage driver tried a few times to use the map Wagoner had left him but couldn't quite reconcile it with the terrain. Objects and places look different to different people, especially in the changing, deceptive light of the desert.

Wagoner found his gold over a century ago, so he and Mullins are long since dead. The circle of trees the prospector planted would be mature trees now, guarding an outcropping of rose quartz somewhere in the south end of the mysterious Superstitions. There must still be gold hidden there else why would Wagoner have wanted to mark the site for his eventual return?

Already a member? Login ».