Ben Johnson, Top Hand

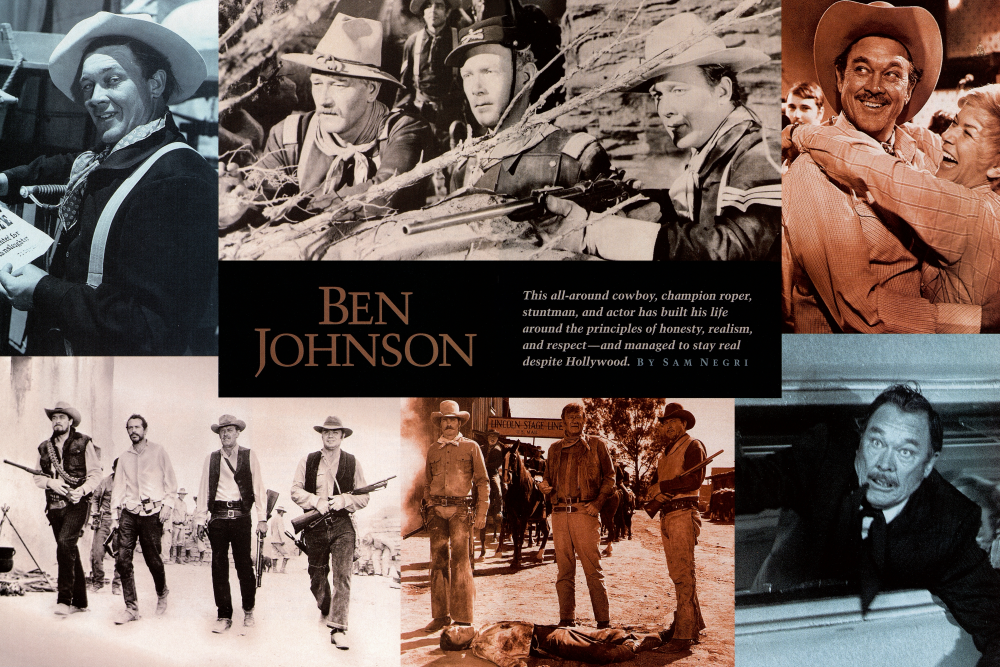

This all-around cowboy, champion roper, stuntman, and actor has built his life around the principles of honesty, realism, and respect—and managed to stay real despite Hollywood. BY SAM NEGRI

BEN JOHNSON

In 1972 when Ben Johnson walked to the stage to accept an Academy Award for best supporting actor in The Last Picture Show, he carried with him a fairly predictable though unfinished speech which would at least have saved him the trouble of having to think in front of so many people. Johnson, a cowboy who had performed in numerous Western movies filmed in Arizona, was in real life a lot like the people he usually portrayed, not particularly at ease in a big crowd.

Hollywood critics later said Johnson stole the show that night by putting away his unfinished speech. He decided against reading it, he told the glittering assemblage, because “... the longer I worked on it, the phonier it got.” Then, holding his shining Oscar in his right hand, he declared, “What I'm about to say will start a controversy around the world:

“This couldn't have happened to a nicer fellow!”

Just a little quip, of course, but there are many who would agree in an instant. The circumstances that brought Johnson his first Oscar show clearly why so many have found him not only “a nicer fellow” but a breath of fresh air in a world where garish pretentiousness is widespread.

Johnson won the Oscar for his role as Sam the Lion, the philosophical owner of a pool hall in a dreary Texas town. The director, Peter Bogdanovich, had sent Johnson a copy of the script and asked him to play the part of Sam.

“It was the worst thing I ever read,” Johnson said. “Every other word that I had was a dirty word, so I turned it down. I don't do dirty movies, and I don't have to say four-letter words around women and kids to make myself a name.” At Bogdanovich's request, John Ford, one of the pioneer directors in the film industry and the man who converted Johnson from a wrangler to an actor, called him and asked him to take the role as a personal favor to him.

“So,” Johnson recalled, “I said to Bogdanovich, okay, I'll do it if you let me rewrite my lines and get rid of all that dirty language. He agreed. I won an Oscar from the American Academy Awards, I won an English Academy Award, a Golden Globe Award, and The New York Film Critics Award — and I didn't have to say one dirty word.” Johnson, who lives in the Phoenix area a few blocks from his 95-year-old mother, has been working in movies as a stuntman or actor since the 1940s. He never became a “star,” and it probably would have surprised him if he had. Johnson was, literally, a cowboy who got into pictures. If you see him as the young Trooper Tyree riding with John Wayne in the classic She Wore a Yellow Ribbon or later in life as the sympathetic rural sheriff in Sugarland Express, it's easy to get the impression he isn't acting at all. Johnson made several movies with John Wayne and also spent time with him at his various cattle operations.

“That's how I know that John Wayne was an honest man. I watched a lot of deals being made, watched him doing swaps, and he was always honest. But he could get pretty mad, too. If somebody tried to beat him out of something or act dishonestly, he'd get mad. I've seen him get into fights when he was pretty mad about something.” On the set, Wayne was an amiable coworker, Johnson said.

“I just returned from the Cannes Film Festival, and all those people over there were asking me about John Wayne John Ford. I told them all the same thing. John Wayne was very professional and a good fellow to work around. If you were willing to work, he was easy to get along with.

(OPPOSITE PAGE, CLOCKWISE FROM TOP, LEFT) Johnson's collection of memorabilia covers 50 years in rodeo and films.

A poster advertises Johnson's Pro-Celebrity Ropin' for Kids charity rodeo.

“With me, I was much better with horses than with acting, but watching John Wayne and watching Ford directing him made it easier for me. It's a shame there aren't more people around today like John Wayne. A lot of the younger people don't even know what honesty means.” Johnson is at home in the culture of the West. Now 77, he continues to compete in rodeo events, and he still lights up a bit when he recalls that in 1953 he won the world championship in team roping.

“That big silver buckle they gave me means more to me than that Oscar,” he said, though he acknowledged the Oscar had a much greater impact on his income than his rodeo award did.

J.P.S. Brown of Tucson, author of a forthcoming biography of Johnson, remarked, “You have to understand that Ben is a very humble person. He was a top hand meaning a cowboy who could handle anything that might come up on a ranch long before he ever became a movie actor. His father was a foreman for Chapman Barnard, a big rancher in Oklahoma who ran about 20,000 mother cows, an enormous operation, and Ben was unique in the movie business because he'd been working on a ranch as a cowboy since the time he was a little kid.” In fact, it was Johnson's skill with horses that turned out to be his admission ticket to the movie business. The late Howard Hughes bought some horses from the ranch where Johnson's father worked for use in a movie he was making in Monument Valley. He needed a wrangler to get the horses from Oklahoma to northern Arizona, and he hired Johnson.

“He wanted me to get those horses from Oklahoma to Arizona and then take them on to Hollywood,” Johnson said. “I loaded them on a boxcar in Tulsa and took them by train to Flagstaff, where they had trucks meet me for the rest of the way to Monument Valley. You might say that's how I got to Hollywood, in a carload of horses.” Johnson's ability with a horse and rope led to a warm friendship with Hughes.

“That movie Hughes was making in Monument Valley, The Outlaws, had a scene where the government had rounded up something like 4,000 horses. Well, Hughes owned this palomino stud named Cherokee Charlie, which he also used in that movie. He had an enormous insurance policy on that horse, and he said to me, 'When they start moving that herd, whatever you do, do not let Cherokee Charlie get into the middle of that bunch of horses.' Well, Hughes owned this palomino stud named Cherokee Charlie, which he also used in that movie. He had an enormous insurance policy on that horse, and he said to me, 'When they start moving that herd, whatever you do, do not let Cherokee Charlie get into the middle of that bunch of horses.' Well, of course, as 'When I left Oklahoma I wasn't even sure which direction Hollywood was, but I could ride a horse pretty good. I was a cowboy from the time I hit the ground.'

Ben Johnson's PRO - CELEBRITY ROPIN FOR KIDS MAR.31-APR.2 1995 RAWHIDE Scottsdale

'I was doubling for John Wayne, Jimmy Stewart, and Joel McCrea, and I would watch the way they did things, but I never really had a desire to be an actor. I could always make a living working on a ranch or in a rodeo.' soon as the herd starts to run, the first thing that palomino does is start running toward the bunch, so I took off after it and roped it real fast. I'd been doing that all my life, but it imprinted on Hughes' mind so much that he became a pretty good friend of mine. He liked to come out and go riding with me all the time, and he'd roll up a hundred dollar bill and tuck it in my shirt pocket. I thought that was pretty good

BEN JOHNSON

Johnson spent his first few years as a stuntman and wrangler, doubling for such famous actors as John Wayne, Gary Cooper, Henry Fonda, Jimmy Stewart, Alan Ladd, and Joel McCrea.

"You know," he said, "when I left Oklahoma I wasn't even sure which direction Hollywood was, but I could ride a horse pretty good. I had no formal education to speak of. I was a cowboy from the time I hit the ground. I knew if a cow weighed 1,000 pounds and brought $10 a hundred, I knew how much that was. But I was fortunate because people accepted my character. I ran my life a certain way. I didn't hobnob with the elites because I didn't do drugs and I didn't drink a lot of whiskey - oh, I might take a drink now and then, but you know what I mean. I think I got a lot of respect from people in the business because of my honesty. Honesty is like a good horse, you know it'll work anyplace you hook it."

When Hughes hired him to bring the horses to Monument Valley, Johnson had been working as a cowboy for $40 a month. Hughes, already a multimillionaire in 1939, gave him $175 a week. "It didn't take me long to figure out this was a good deal," Johnson said.

After working as a wrangler and stuntman, Johnson got his first speaking part around 1943 in a movie called Red Riders. His role called for him to ride up on his horse, dismount, and run into an office and declare, "I have a telegram for you from the United States Treasury Department."

He studied the line eight days and eight nights, he said, and then muffed it.

"I messed up the shot about three times before I could remember my line."

Johnson never had any training as an actor. He was a classic case of on the job training.

"I was doubling for people like John Wayne, Jimmy Stewart, and Joel McCrea, and I would watch the way they did things, but you know, I never really had a desire to be an actor. I always had something else to do. I didn't sit around waiting for the phone to ring. I could always make a living working on a ranch or in a rodeo."

Johnson's acting ability also benefited from exposure to some of the most talented directors of the last 50 years. After he left Howard Hughes, the legendary John Ford hired him as he was embarking on his series of epic cavalry movies in northern Arizona.

"I worked with Ford, Steven Spielberg [He was in Sugarland Express, the first movie Spielberg directed], Peter Bogdanovich, and Sam Peckinpah [in the classic Western, The Wild Bunch], and I listened to what they had to say. That John Ford, I worked for him for six years. I mean, he was a mean old b d, but if you listened to him, you could learn something. He was a real educator. The last words Ford ever said to me was, 'Ben, don't forget to stay real.' I think that's pretty good advice anywhere."

In 1953 Johnson took a year off from the movie business to compete full-time in rodeos.

"My dad was a world champion three or four times, so I wanted to be. Fortunately I won the world championship in team roping, but that year I didn't have $3. All I had was a wore-out automobile and a mad wife. But, you know, I am the only cowboy that ever won an Oscar in the movies and a world championship in rodeoing."

In later years, Johnson started sponsoring the Ben Johnson celebrity rodeos in major cities throughout the country, including the Phoenix area, to raise money for sick or deprived children.

Johnson eventually had roles in approximately 300 movies, most of them Westerns. At least a dozen of them were shot amid the spectacular buttes and mesas of Monument Valley or along the bottom of Canyon de Chelly in the heart of the Navajo reservation, and some at the Old Tucson movie set, which was partially destroyed by fire in 1995. Johnson remained obscure, however, until he was hired for a supporting role in Sam Peckinpah's 1969 bloodfest, The Wild Bunch, starring William Holden.

Peckinpah, who had a reputation as a wild man, was, in fact, a near lunatic, Johnson said.

"The first time I met him was in 1965 when he asked me to appear in Major Dundee, with Charlton Heston. I went to his office to meet him, and I was sitting across the desk from Sam when a stuntman comes in. Well, Sam abused him something terrible, yelling at him. He did it there, in front of me, and when the man walked out, I just said, 'I can't work for you.' He said, 'Why not?' "I said, 'If you did to me what you did to that man there, I'd hit you right in the d.n nose and you'd run me out of the business, and I'm not ready to leave.' 'Well,' he said, 'I'm not that bad. I was just trying to scare him a little.' "

Peckinpah evidently enjoyed scary encounters of any kind. As Johnson recalled: "Sam was a fatalist. He was a pretty talented guy, but he didn't care much about life, and some of what he did, he didn't care much about the outcome as long as the movie had blood and guts and thunder. He was pretty nuts. I saved his life about a dozen times, I guess. He'd start drinking whiskey and taking pills, and he'd go crazy. He'd go into a bar, walk through the place, find the biggest guy there, and pick a fight with him. He was crazy."

Ben Johnson, on the other hand, was eminently sane, which is why, some say, he never became a big celebrity in Hollywood.

"Ben was a very good businessman and invested the money he made in movies very wisely, and in a way that was why he never learned to be a great actor," a friend said. "He didn't have to. The fact is he was doing so well that he didn't need Hollywood. And his ego definitely didn't need Hollywood, either."

I asked Johnson about that statement before I left his home in Mesa.

"Well," he said, "I can't handle phony people, and there are a lot of them in Hollywood. I've built my life around the principles of honesty, realism, and respect, and if the people in Hollywood are so pumped up on themselves they can't deal with that, I say the h.. I with 'em. I think I've won the respect of some people over there, and I think I managed to stay real.'"

Author's Note: This year's Ben Johnson's Pro and Celebrity Ropin' for Kids event will take place March 29-31, at Rawhide Western Town & Steakhouse, 23023 N. Scottsdale Road, Scottsdale; (602) 502-5600.

Tucson-based Sam Negri watched several Ben Johnson movies before interviewing him, and afterward concluded it was clear that Johnson was usually playing himself: a disarming and straight-forward man of the Old West.

Already a member? Login ».