Phoenix's Popular Urban Wilderness

IN PHOENIX YOU CAN HEAD FOR THE MOUNTAINS WITHOUT LEAVING THE CITY

IF YOU LIVE IN OR VISIT PHOENIX, there may come that time when things get to be a bit much. The weather's great, but Phoenix is now a city of a million-plus and the traffic, the noise, the pressures well, the magic word on occasion is “escape.” What you do is, you head for the mountains. And you do it without ever leaving town. For Phoenix has what exists nowhere else: well within its municipal borders lies a great preserve of mountains and virgin desert. It's the largest urban park in the world. But it's more than that. It's an oasis in the midst of the hurly-burly of urban life. Its official name is the Phoenix Mountains Preserve. It encompasses more than 23,500 acres of scenic getaway located almost literally at every Phoenician's back door. It's to Phoenix what the harbor and beaches are to San Diego and the lake is to Lake Tahoe.

John Driggs, who as mayor in the early 1970s helped get the preserve going, considers it “a unique preserve-park system.” Ruth Hamilton, who fought for years to get the preserve and then keep it inviolate, calls it “the last vestige” of the Old West.

City parks officials estimate that the preserve is used by nearly 3.5 million people a year. (Total annual attendance at the Grand Canyon is about 5 million.) One segment of the preserve, the most recently acquired portion, spreads across more than 7,000 acres of the city's uppermiddle reaches. It anchors on an eminence known as North Mountain and takes in such other rises as Squaw Peak, Shaw Butte, and Lookout and Shadow mountains. Homes flow right up to its periphery, but there they stop cold. There are points of access at many places around that periphery. All you have to do is park and go in to hike, jog, mountain bike, ride horseback, picnic, ogle the desert flowers in spring, whatever.

The other segment of the preserve is along the southern edge of the city, and it is larger and older in formal park years. It's the 16,500-acre South Mountain Park, of and by itself the largest municipal park in the U.S. It embraces a range rising to an elevation of 2,660 feet.

South Mountain Park was put together back in the 1920s and '30s. You're aware of that when you see the more-than-halfcentury-old native stone and adobe structures park headquarters and ramadas built by the Civilian Conservation Corps of Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal, conceived to give jobs and healthful outdoor living to the nation's jobless youth. The south and north segments were brought together as a single entity in 1978

PHOENIX MOUNTAINS PRESERVE

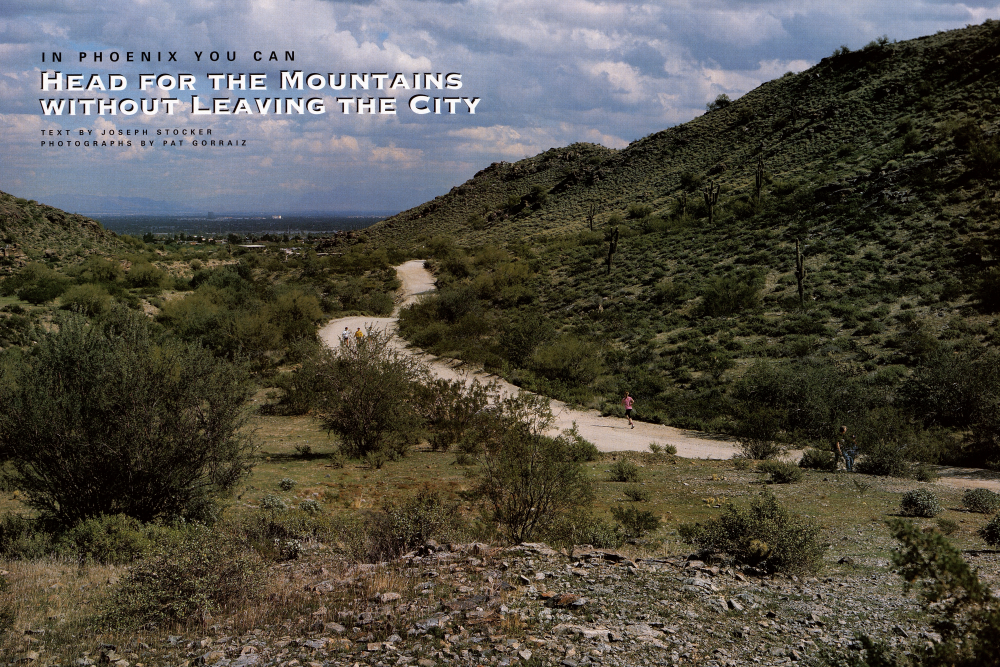

(PRECEDING PANEL, PAGES 10 AND 11) The Phoenix Mountains Preserve will forever remain one of the city's most magical and unexpected treats: a "remote" mountain wilderness nestled within an urban sprawl. Here runners and hikers find both relaxation andarecreation along Pima Canyon Trail, which runs through South Mountain Park in the southernmost and oldest section of the preserve. (FAR LEFT) A horseback rider heads up Squaw Peak Summit Trail in the upper part of the preserve. (ABOVE) After a long climb, Ann Gorraiz savors a cool drink while Fred Griffin surveys Squaw Peak. (LEFT) Mary Halfman, a founding board member of Mountain Bike Association of Arizona, takes a break on a ride on the Dreamy Draw. and have existed as the Phoenix Mountains Preserve ever since.

There are 50 miles of designated trails in the north segment; 58 in the south (plus 26 miles of paved roadway). In the South Mountain portion of the preserve, you can go nearly 14 miles from almost the easternmost edge to almost the westernmost along the National Trail.

In the northern segment, you can pick up the Charles Christiansen Memorial Trail at either northwest or southeast access points and hike, mountain-bike, or ride horseback across the whole preserve. Distance: 10.7 miles.

The most popular trail is the one that climbs Squaw Peak. It's only 1.2 miles, but it's very much up from 1,400 to 2,608 feet, a 19 percent grade. Squaw Peak is the climb of choice for the city's exercise enthusiasts. In all, about 10,000 a week onthe average climb the peak. Most walk. Some, the super-fit, run. A few persist in doing it in the formidable heat of August. And there are those who climb it at night.

They're a diverse bunch, those climbers. Ruth Finn, a lawyer in her 70s who climbs for the health of it, says she's seen four year olds and couples in their 80s clambering up Squaw Peak. "I've seen jocks running up the mountain in 17 minutes," she says. "I saw two women, obviously newly divorced, banging on the rocks, apparently venting their anger at their husbands, one exclaiming, 'My husband is worse than your husband!' " A real catharsis, Squaw Peak.

If you really want to get away from the city, west of Squaw Peak there's a valley, a kind of a bowl, in which - just minutes from where you parked your car - you're completely out of sight of the city. I hikedin there recently with photographer Pat Gorraiz. The mountains around us shut out not only the sight but the sounds of the city. No shoosh of traffic. No nothing. Just quiet. Now that's an escape!

But then if you want thrilling panoramic views of the city and its skyscrapers, they're to be had from the crest of any of those stark desert mountains.

So protected is the preserve that wildlife abounds. Walk quietly. Look closely. You just might spot coyotes, Gila monsters, horned lizards, chuckwallas, jackrabbits, cottontails, ground squirrels, kit foxes. And more than 50 species of birds have been sighted in the preserve: bluebirds, cardinals, mockingbirds, hummingbirds, owls, hawks, turkey vultures, and on and on.

When it comes to flora, the preserve embraces many of the plants native to the Sonoran Desert: that Arizona trademark,

PHOENIX MOUNTAINS PRESERVE

(RIGHT) Watching wildlife is another popular pastime in the pristine reaches of the mountains preserve. Here a Gambel's quail rests in a snag above a patch of sunny brittlebush. (BELOW, RIGHT) Our photographer came across this desert tortoise walking along a hiking trail. (FAR RIGHT) In South Mountain Park, saguaros flank the National Trail, which is part of a statewide trail system.

the tall, tubular saguaro cactus, and its cousins, the barrel cactus, hedgehog, pincushion, prickly pear, ocotillo, jumping cholla. The trees: mesquite, paloverde, ironwood. And the flowers that bloom in spring (assuming a reasonably beneficent winter rainfall): vividly orange desert poppies, bluish-lavender lupine, yellow brittlebush, and a baker's half-dozen of other little beauties. How did all this come about? How do you get a fast-growing city to pony up $71 million to keep a lot of land from being built on so folks can go back to Nature? Many people have been involved over the years. But there's a kind of consensus that three women - Dorothy V. Gilbert, Ruth Hamilton, and Maxine Lakin - have perhaps done more to make the preserve a reality than anyone. All have chaired the city parks board and presided over the principal champion of the preserve, the Phoenix Mountains Preservation Council. All are in their upper years (they like to call themselves the "grandmothers of the Phoenix Mountains Preserve"). All love horses and the out-of-doors. And all have devoted much of the past quarter-century to forging and protecting - those 23,500-plus acres of mountains and desert. (Accordingly, and appropriately, the city has acknowledged its debt to the three women by naming a trio of trails after them.) Penny Howe, presently on the city parks board, thinks Dorothy Gilbert (she prefers "Dottie," actually) had the "original vision" of the preserve. She lived - and still lives - in the northern part of the city and often rode horseback into the nearby mountains with her children. She saw homes creeping up not so distant hillsides and roads scarring the mountain slopes. She and her husband, Gil, a local businessman, sensed that something ought to be done, and quickly. "We just knew how wonderful it was to have this open space," she says. Dottie Gilbert did what came naturally. She organized a horseback breakfast ride up to a high pass behind Squaw Peak for Mayor John Driggs and the city council. The year was 1971. As the riders approached the pass, they smelled bacon cooking, and Mayor Driggs' five-year-old son, Andy, spied a coyote. The idea of salvaging an out-ofdoors adjacent (at least figuratively) to everybody's indoors took hold among the politicos. Charles Christiansen, newly ensconced as the city parks director, had taken a horseback ride, also. And he, too, had come back impressed. He persuaded the city fathers to hire Paul Van Cleve, a planner and also a horseman, to study the mountains and see what might be done to get them. Van Cleve spent a year at it, came back and said, in effect, go for it.

"The grand scale and rugged character of these mountains," wrote Van Cleve in his report, "have set our life-style, broadened our perspective, given us space to breathe, and freshened our outlook."

In 1973 a bond issue was approved by the voters, and the city started buying land. There were six more bond elections. Two failed but four passed, and with that money and funds from federal revenue-sharing, the city bought more land.

Important people began casting covetous eyes on all that pretty desert. A golf course was proposed here, a rodeo grounds there. Somebody suggested that two percent of the preserves be set aside for hotel and resort development.

The Phoenix Mountains Preservation Council fought every attempted land grab. Finally legislation was passed requiring a public vote be held on preserve developAmendment proposals (except possibly for the addition of a freeway loop through a corner of South Mountain Park).

As of this writing, the city's desert-andmountain escape hatch was less than 70 acres shy of being complete.

Says parks Director James Colley: "When people began this program in the early 1970s, I doubted seriously if they ever dreamed we would spend the kind of money we've spent, or that a local government would make that kind of commitment. In my opinion, it's probably one of the major accomplishments of this city indeed, of any city that I know."

Ruth Hamilton puts it like this: "It just shows what a bunch of little old ladies can do."

Author's Note: Trail maps of the North and South Mountain preserves and descriptive literature can be obtained at public libraries, district offices of the Phoenix Parks, Recreation and Library Department, and ranger stations in the two preserves. Call ahead to make sure the location offers the kinds of activities and recreation you are looking for. For information on South Mountain Park, telephone (602) 495-0222; to ask about the Phoenix Mountains Preserve, call (602) 262-7901.

Already a member? Login ».