Wickenburg: Where the Dudes Went

WICKENBURG'S Dude Ranch Yesterday

AFTER A SUMMER THUNDERstorm in 1946, the Hassayampa, almost always so bone dry that it's called the "upside-down river," became a raging torrent. Harry Sydney, sometime guest and then a hired hand at Remuda Ranch, took an air mattress called the Snoozer Cruiser and kept a long-standing promise. Friends and doubters gathered at the bridge and waited, myself among them. We looked dubiously at the boiling mudbrown water. Minutes passed. Upriver a bit of flotsam caught in the flood gradually materialized into Harry. As he sped past in the heaving water, he looked as relaxed as if he had been floating in the swimming pool back at Remuda. A great cheer from the gallery followed him as he swept on by and disappeared downstream.

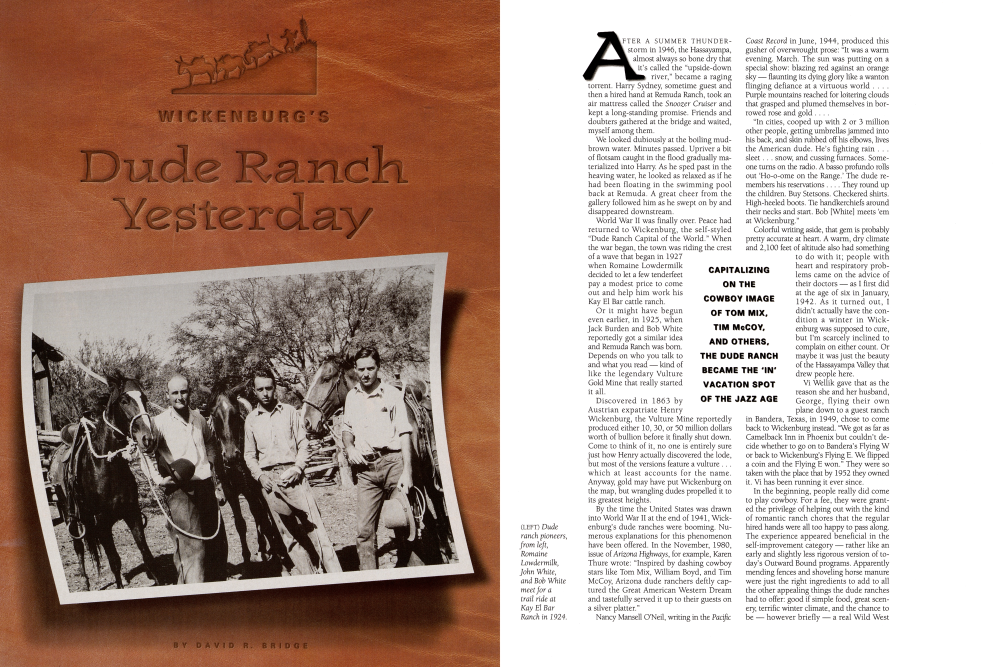

World War II was finally over. Peace had returned to Wickenburg, the self-styled "Dude Ranch Capital of the World." When the war began, the town was riding the crest of a wave that began in 1927 when Romaine Lowdermilk decided to let a few tenderfeet pay a modest price to come out and help him work his Kay El Bar cattle ranch. Or it might have begun even earlier, in 1925, when Jack Burden and Bob White reportedly got a similar idea and Remuda Ranch was born. Depends on who you talk to and what you read - kind of like the legendary Vulture Gold Mine that really started it all.

Discovered in 1863 by Austrian expatriate Henry Wickenburg, the Vulture Mine reportedly produced either 10, 30, or 50 million dollars worth of bullion before it finally shut down. Come to think of it, no one is entirely sure just how Henry actually discovered the lode, but most of the versions feature a vulture. which at least accounts for the name. Anyway, gold may have put Wickenburg on the map, but wrangling dudes propelled it to its greatest heights.

By the time the United States was drawn into World War II at the end of 1941, Wickenburg's dude ranches were booming. Numerous explanations for this phenomenon have been offered. In the November, 1980, issue of Arizona Highways, for example, Karen Thure wrote: "Inspired by dashing cowboy stars like Tom Mix, William Boyd, and Tim McCoy, Arizona dude ranchers deftly captured the Great American Western Dream and tastefully served it up to their guests on a silver platter."

"In cities, cooped up with 2 or 3 million other people, getting umbrellas jammed into his back, and skin rubbed off his elbows, lives the American dude. He's fighting rain sleet. snow, and cussing furnaces. Someone turns on the radio. A basso profundo rolls out 'Ho-o-ome on the Range.' The dude remembers his reservations They round up the children. Buy Stetsons. Checkered shirts. High-heeled boots. Tie handkerchiefs around their necks and start. Bob [White] meets 'em at Wickenburg."

CAPITALIZING ON THE COWBOY IMAGE OF TOM MIX, TIM MCCOY, AND OTHERS, THE DUDE RANCH BECAME THE 'IN' VACATION SPOT OF THE JAZZ AGE

Colorful writing aside, that gem is probably pretty accurate at heart. A warm, dry climate and 2,100 feet of altitude also had something to do with it; people with heart and respiratory problems came on the advice of their doctors - as I first did at the age of six in January, 1942. As it turned out, I didn't actually have the condition a winter in Wickenburg was supposed to cure, but I'm scarcely inclined to complain on either count. Or maybe it was just the beauty of the Hassayampa Valley that drew people here.

Vi Wellik gave that as the reason she and her husband, George, flying their own plane down to a guest ranch in Bandera, Texas, in 1949, chose to come back to Wickenburg instead. "We got as far as Camelback Inn in Phoenix but couldn't decide whether to go on to Bandera's Flying W or back to Wickenburg's Flying E. We flipped a coin and the Flying E won." They were so taken with the place that by 1952 they owned it. Vi has been running it ever since.

In the beginning, people really did come to play cowboy. For a fee, they were granted the privilege of helping out with the kind of romantic ranch chores that the regular hired hands were all too happy to pass along. The experience appeared beneficial in the self-improvement category - rather like an early and slightly less rigorous version of today's Outward Bound programs. Apparently mending fences and shoveling horse manure were just the right ingredients to add to all the other appealing things the dude ranches had to offer: good if simple food, great scenery, terrific winter climate, and the chance to be however briefly a real Wild West Coast Record in June, 1944, produced this gusher of overwrought prose: "It was a warm evening. March. The sun was putting on a special show: blazing red against an orange sky-flaunting its dying glory like a wanton flinging defiance at a virtuous world Purple mountains reached for loitering clouds that grasped and plumed themselves in borrowed rose and gold."

WICKENBURG

Cowboy, the only uniquely American hero. According to author Karen Thure, some ranches even furnished their guests with toy six-shooters to make the illusion complete. "A month or even an entire winter at a guest ranch was becoming the 'in' holiday of the Jazz Age," she reported.

It took more time to get to Wickenburg from distant points like Ohio or New Jersey in those days. Many arrived, accompanied by heavy trunks, on the Santa Fe Railroad. (When the trains stopped running years later, the company with regrettable corporate myopia scheduled the historic old depot for destruction. Thanks largely to the efforts of Vi and George Wellik, however, it was faithfully restored instead and now houses the town's chamber of commerce.) Wickenburg also enjoyed the good fortune of being on the main route to the Grand Canyon. In fact, it was difficult to cross Arizona in any direction without passing through the town. Since it took so long and so much effort to get there from dude country, it made sense to stay longer Wickenburg's Mayor Harold P. Sullivan, in response to entreaties from an "Annex Phoenix" committee, had declared the town council's willingness to do just that. Facetious or not, things had never looked rosier than they did on the eve of Pearl Harbor.

At first, little notice of the war that engulfed the world appeared in the pages of the Sun. The regular column titled "At The Ranches" continued to report social notes on who came and went and did what as though nothing had changed. I even found strangely haunting records there of my own performance in Remuda's weekly rodeos. Western troubadour Powder River Jack (a huge man made even more gigantic by what looked to my six-year-old eyes like a 50-gallon hat) and his associate, Kitty Lee, kept on singing Western ballads and telling tall tales around Remuda's after-dinner fire. Browsing through the paper's pages until well into 1942, you wouldn't have guessed what was happening in the rest of the world. By 1943, however, that had changed, Than just a week or two. To encourage that very trend, Remuda Ranch operated its own fully accredited school. Guests' children could continue their education without interruption while they themselves went out on breakfast rides or lollygagged around the pool. When school was out, there were trusty wranglers to take the little darlings off on trail rides of their own. On the American Plan (lodging and meals included), rates were $5 to $11 per day!

Dude ranches began popping up everywhere, eventually numbering more than 30. By April, 1940, the town was so full of itself that the local paper, the Wickenburg Sun, trumpeted the possibly tongue-in-cheek headline: "Wickenburg will absorb city of Phoenix."

And the stories mostly concerned rationing, scrap paper and metal drives, war bond campaigns, and local citizens who were caught up in the conflict. According to a little book with the garbled title The Right Side Up Town on the Upside Down River, Army Capt. Harry Claiborne selected Wickenburg as the ideal place to set up a glider pilot training school. The ever-present vultures lazily circling in the sky could be used to spot thermal updrafts that would keep the gliders aloft for hours. While waiting for barracks to be built, Claiborne rented Remuda for the school headquarters. Only a clairvoyant could have known then that the forces set in motion by the war would eventually number the dude ranch boom among the casualties.

The main activity fueling that boom was, of course, horseback riding. You could take breakfast, picnic, cookout, moonlight, chuckwagon, or just plain ride rides. Threading your way among giant saguaros; snaking up steep, rocky trails on your surefooted steed; hearing the sudden buzz of an alarmed rattlesnake in the brush, and waiting while the wrangler dispatched the hapless creature with his lariat (with real luck, you might get the severed rattle as a trophy); savoring the rich aromas of bacon frying and coffee brewing in the sharp, clean air all this exerted a powerful appeal.

On more than one such outing, I brought consternation to a wrangler tracking down an agitated rattler by getting off my horse and following the reptile. In those days, the cowboy simply picked me up and put me back on my horse. It's unlikely that he ever thought about the lawsuits that might follow if I had been bitten or fallen on my head while dismounting. But the age of litigation put an end to such carefree attitudes, and the concomitant rising cost of liability insurance halted guest participation in ranch work.

Abandoning the rails in the postwar years, Americans took to automobiles and jet planes in everincreasing numbers as their travel habits shifted from relative stasis to high-speed mobility. The kind of leisurely and extended holiday fostered by the dude ranches became incompatible with the new urgency to pack expanded activity into diminished time.

During the 1950s, the interstate highway system came into being. Was it mere coincidence that by the end of that decade the Western once so dominant on television and at the movies had almost vanished from the American scene? Cowboys gave way to cops as our entertainment fare. When the so-called Brenda Cutoff a part of Interstate 10 that bypassed Wickenburg went through in 1973, the town was expected to "shrivel up and blow away," as Kenneth Arline wrote in The Phoenix Gazette. By then many of the dude ranches had already bitten the dust. Remuda gradually suffocated under the weight of trying to support too many family members on staff, according to Jack Burden's sons, John and Dana. Today the place is a clinic for women with eating disorders. Evidently there is some therapeutic connection between horses, horseback riding, and these disorders so it is still a love affair with the horse that makes Remuda go. Vi Wellik, who agreed with John and Dana's analysis of the Remuda's metamorphosis, surprised me when she added that the guest ranch business had always been a marginal moneymaker anyway. "To get good employees these days you have to pay good salaries. We maintain a ratio of one employee for every two and a half guests. When you add the cost of upkeep and improvements, liability insurance, and the fact that the business is both seasonal and unpredictable, your profit margin becomes pretty thin. I only stay in the business because I love it, and I'm lucky enough to have the personal resources to carry it." Edie Hayman shed more light on this at lunch one day. She and her late husband, Dallas Gant, opened Rancho de los Caballeros in 1948. She stunned me by revealing how much it costs every year just to reopen the place. Largest and ostensibly the most successful of the five survivors, Los Cab with its 18-hole championship golf course evolved over the years into a true resort. The business conferees who frequently gather there these days may be a far cry from the dudes of yesteryear, but the ranch itself never looked better. Arizona has many ghost towns. Some, like Jerome and Crown King, are quite celebrated as such despite pite the fact that they are undeniably inhabited by live populations. Wickenburg might easily Have joined their ranks as a curiosity of the past when the dude boom began to fade like the gold rush that preceded it. Instead the town moved resolutely into the future. In many ways little has changed since the 1940s, Wickenburg remains a magnet for those still drawn by the allure that first gave it the title "Dude Ranch Capital of the World."

WHEN YOU GO

Getting there: Wickenburg is 58 miles northwest of Phoenix. All phone numbers are area code 520. Things to see and do: Local attractions include the excellent Desert Caballeros Western Museum, 684-2272; the lush Hassayampa River Preserve, 684-2772, with its Nature trails and rich birdlife; and Robson's Mining World, 685-2609, a reconstructed mining town 16 miles north of Wickenburg. Accommodations: Guest ranches in the area include: Rancho Casitas, six miles north of Wickenburg off State 89/93, P.O. Box A-3, Wickenburg, AZ 85358; 684-2628. Wickenburg Inn Tennis & Guest Ranch, seven miles northwest of Wickenburg on State 89, P.O. Box P, Wickenburg, AZ 85358; 684-7811. Flying E Ranch, four miles west of Wickenburg and one mile south of U.S. 60, 2801 W. Wickenburg Way, P.O. Box EEE, Wickenburg, AZ 85258; 684-2690. Kay El Bar Ranch, three miles north of Wickenburg off State 89/93 on Rincon Road, P.O. Box 2480, Wickenburg, AZ 85358; 684-7593. Rancho de los Caballeros, five miles west of Wickenburg and two miles south of U.S. 60 on Vulture Mine Road, 1551 S. Vulture Mine Road, Wickenburg, AZ 85390; 684-5484. For more information, contact the Wickenburg Chamber of Commerce, P.O. Drawer CC, Wickenburg, AZ 85358; 684-5479.

Already a member? Login ».