Bonita Creek Birding

Something

omething important must have been happening.

Maybe it was the arrival of a couple of two-legged creatures in a white vehicle. You don't see much of that during the week at the mouth of Bonita Creek; the birds, evidently, were determined to spread the word, or maybe just comment. Not being fluent in bird-speak, I couldn't tell you for sure, but whatever was being communicated in those towering cotCottonwood trees was loud and urgent, maybe even a bit gossipy.

"We've got our own little symphony here," said Diane Drobka, my guide from the Bureau of Land Management. "I just can't identify all of the instruments."

Diane and I had traveled a mere 20 miles north of Safford, 75 percent of that on a paved road and the rest on an excellent dirt road, to spend some time at one of the best-kept secrets in southeastern Arizona: a bird-watchers' paradise at the southern end of the federally protected Gila Box. But "secret" is really stretching things a bit. No one is trying to hide the splendors of the Bonita Creek watershed. It's relatively unknown because it is removed from any well-traveled tourist route.

A 15-mile segment of Bonita Creek and 23 miles of the Gila River are included in the Gila Box Riparian National Conservation Area, which means the area is federally protected, ecologically valuable and unusual, and open to the public. Rivers and streams that actually carry water year-round are rare in Arizona. Any bird could tell you that if it could learn the lingo. Water in this country is mesmerizing, which is why - even before we started scouring the trees and cliffs for birds we had to get our fill of the spectacle of moving water, even rushing water, tumbling out of Bonita Creek into the wide and muddy stream of the Gila River. In a land where summer temperatures frequently top 100° F. and rainfall is scarce, moving water is a revered phenomenon.

It also is the ingredient that nourishes the abundant diversity of wildlife in Bonita Creek. Hundreds of birds, as well as mountain lions, bears, javelinas, and deer, flourish in the vast thickets thatflank the creek, mainly because of the nu-tritious flora and fauna made possible by dependable water.

THE BIRDS OF BONITA CREEK BY SAM NEGRI

THE BIRDS OF BONITA CREEK

(LEFT) Bonita Creek's permanent water flow supports a wide variety of desert flora and fauna. Here, a grove of cottonwoods frames the streambed. (ABOVE) Wildlife viewing platforms provide a treetop vista of the Gila Box and Bonita Creek riparian area. BOTH BY DAVID H. SMITH Some of the birds in this area are rare, and that was one of the main attractions for me. A few years earlier, I had crossed another portion of Bonita Creek in search of an isolated cliff dwelling known as Pueblo Devol. (See Arizona Highways, Feb. '97.) Just as BLM archaeologist Gay Kinkade drove our pickup into the creek on that day in February, I looked up and saw a bald eagle flying north above the stream. Cliffs 60 and 70 feet high rose from the creek bed in that area, prime real estate for an eagle's nest. That brief encounter convinced me I would return to see what other riches were to be found in this isolated country.

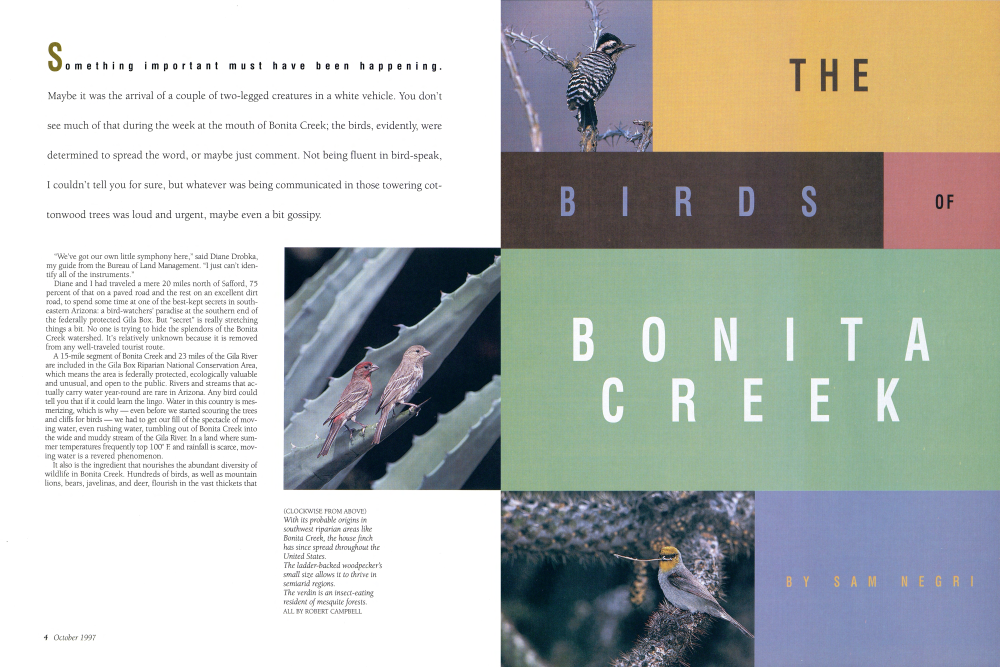

It seemed presumptuous, I thought, to expect to encounter another bald eagle, so I'd set my hopes on seeing the rare and stately black hawks. There are roughly 250 pairs of black hawks in the United States, and the federal government has categorized them as a threatened species. Black hawks average 20 inches in length and have a wingspan of four feet. They tend to populate canyons in the northern portion of Arizona, and there are only two places they can be found in the southern half of the state: Aravaipa Canyon, where a day-use permit is required, and Bonita Creek, where permits are not necessary. Diane kept scanning the tall cottonwood trees above Bonita Creek, searching for black hawk nests. During the next hour, we encountered a small army of birdlife that included a goldfinch, two ladder-backed woodpeckers happily mating on a dead tree limb, a white-crowned sparrow, a couple of rough-winged swallows, a canyon wren, a yellow-rumped warbler, a Bell's vireo, a solitary vireo, a house finch, a common virden, a black-chinned hummingbird, a couple of phainopeplas, and a turkey vulture. I've excluded those birds we could hear but not see.

I began to wonder whether the black hawks were going to remain elusive (though admittedly a bird that large would have trouble hiding), when I heard Diane calling me in a hushed voice from a dry spot above the creek about 200 feet away.

"The cliff on your left. Look!"

Just below the rim of the cliff, two black hawks glided around each other, riding the thermals in a tight circle as the air grew warmer in the late morning.

Suddenly, about 30 feet away from the circling hawks, I spotted a third perched on a dark brown boulder just below the rim of the cliff. It sat stone still for nearly 10 minutes, then abruptly leaned into the sky and took flight over my head, providing an excellent view of the distinctive band across its broad tail.

"To me they always look like flying umbrellas," said my friend Rick Taylor, a birding tour guide based in Tucson. I was telling Taylor about my trip a few days after the fact and asked him how it happened that so few bird-watchers were aware of Bonita Creek.

"The main reason birders don't go to Bonita Creek is that it isn't on the way to Ramsey Canyon in the Huachuca Mountains or Cave Creek in the Chiricahua Mountains. Most birders arrive in Arizona

Arizona Highways 7

BIRDS OF BONITA CREEK

through Phoenix or Tucson, and most of them are going to go to the border mountain ranges because they want to see all those Mexican birds, the elegant trogon in particular, that barely make it into the U.S. in southern Arizona.

"If Bonita Creek had the same kind of access that a Tombstone or Sierra Vista has, there'd be all kinds of people up there," Taylor noted. "It's off the beaten track. Maybe that's why you still have the habitat in Bonita Creek to support black hawks. You don't have huge numbers of people going through there."

Certainly I couldn't argue with that last point. On the day I visited the area with Diane Drobka, we did not encounter another human being and never even passed another vehicle.

Which is not to say the area is unknown or somehow intimidating. Residents in the vicinity of Safford, some 140 miles northeast of Tucson and roughly 165 miles east of Phoenix, are well aware of the point where Bonita Creek empties into the Gila River at the south end of the Gila Box. In a wide, flat clearing above the creek, BLM has built a small campground under the stands of enormous cottonwood, sycamore, and mesquite trees, and families from nearby towns come here to picnic on weekends.

Ironically, Bonita Creek is one of those areas that is wilder today than it used to be. The long shadows cast by cliffs above the Bonita watershed today lie like a blanket over an enormous unpopulated landscape known to a handful of archaeologists and to residents in the small farming communities of Graham County. But for sporadic periods during the last 700 years, these deep canyons were well used, first by Indian farmers, who planted in the flats along the stream, and later by woodcutters selling fuel to the copper mines that burgeoned at nearby Clifton in the mid-1800s.

Roughly 800 years ago, Indians - probably Anasazi-built little apartment houses into the cliffs along Bonita Creek. Those Indians gathered stones and mud and carried them to alcoves in the cliffs. Then, stone by stone, they patiently built walls to partition the spaces, left small windows that offered a strategic view of the creek and nearby hills, and covered their rooms with branches and brush. Pueblo Devol, with an estimated 50 rooms, was probably the largest of the three major cliff dwellings along Bonita Creek.

Today, however, the Bonita Creek watershed, which backs up against the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation to the north, is remarkably quiet. With neither industry nor any major roads nearby, the only sounds to be heard are the calling of birds, the trickle of the creek, and the wind pushing its way through the tops of the trees.

BLM Recreation Officer Jonathan Collins says that wildlife viewing platforms have been erected on the hill above Bonita Creek so that visitors, perched near the treetops, can look out over the Gila Box and the dense riparian vegetation along Bonita Creek and see birds and other wildlife without damaging the fragile streambed.

The birds, of course, are indifferent to the platforms, and so they continue coming to Bonita Creek in droves.

WHEN YOU GO

Bonita Creek is not near any major city or freeway. From Phoenix or Tucson, drive east on Interstate 10 to Exit 352, State Route 191. Turn north for 35 miles to Safford. Drive north from Safford on Eighth Avenue and follow the signs to the airport. Two miles beyond the airport, turn left and follow the small BLM signs to Bonita Creek. The elevation along Bonita Creek ranges from 3,100 to 4,000 feet. When summer rains begin, flash floods are possible, which means the sky may be perfectly clear overhead, but heavy rains upstream may produce a sudden, devastating wall of water with no warning. All other seasons are comfortable, and late fall, when the cottonwoods turn golden, is especially beautiful. Because there are cattle grazing upstream, visitors should avoid ingesting the waters of Bonita Creek.

Keep in mind that while Bonita Creek is accessible in an ordinary passenger car, the condition of the unpaved road is not entirely predictable.

For more information: The Bureau of Land Management, Safford Office, 711 14th Ave., Safford, AZ 85546-3321; (520) 428-4040.

Already a member? Login ».