Prayers in Stone

FETISHES PORTALS TO GOOD FORTUNE

Fetishes are among the oldest devices used by humans as gateways to the spirits, wards against misfortune, and magnets for powers beyond the capabilities of ordinary people.

The form that a fetish takes depends upon the time, the people, and the beliefs of the individual. A rabbit's foot, a clump of feathers, a lucky cap, a stone animal, a symbol painted on a scrap of cloth or paper, an ear of corn all can be fetishes.

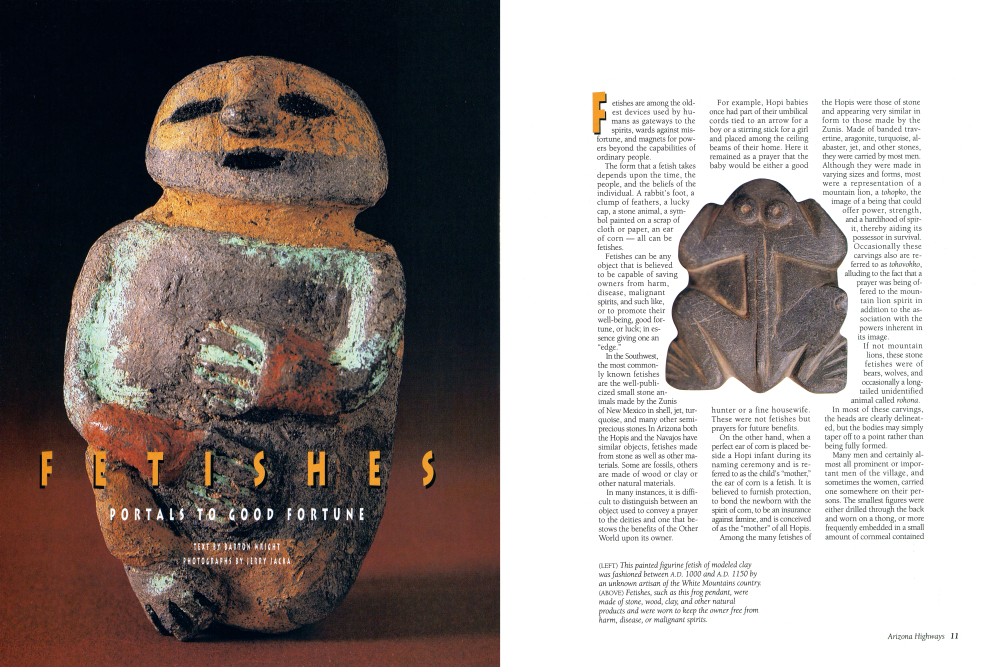

Fetishes can be any object that is believed to be capable of saving owners from harm, disease, malignant spirits, and such like, or to promote their well-being, good fortune, or luck; in essence giving one an “edge.” In the Southwest, the most commonly known fetishes are the well-publicized small stone animals made by the Zunis of New Mexico in shell, jet, turquoise, and many other semi-precious stones. In Arizona both the Hopis and the Navajos have similar objects, fetishes made from stone as well as other materials. Some are fossils, others are made of wood or clay or other natural materials.

In many instances, it is difficult to distinguish between an object used to convey a prayer to the deities and one that bestows the benefits of the Other World upon its owner.

For example, Hopi babies once had part of their umbilical cords tied to an arrow for a boy or a stirring stick for a girl and placed among the ceiling beams of their home. Here it remained as a prayer that the baby would be either a good hunter or a fine housewife. These were not fetishes but prayers for future benefits.

On the other hand, when a perfect ear of corn is placed beside a Hopi infant during its naming ceremony and is referred to as the child's “mother,” the ear of corn is a fetish. It is believed to furnish protection, to bond the newborn with the spirit of corn, to be an insurance against famine, and is conceived of as the “mother” of all Hopis. Among the many fetishes of the Hopis were those of stone and appearing very similar in form to those made by the Zunis. Made of banded travertine, aragonite, turquoise, alabaster, jet, and other stones, they were carried by most men. Although they were made in varying sizes and forms, most were a representation of a mountain lion, a tohopko, the image of a being that could offer power, strength, and a hardihood of spirit, thereby aiding its possessor in survival. Occasionally these carvings also are referred to as tohovohko, alluding to the fact that a prayer was being offered to the mountain lion spirit in addition to the association with the powers inherent in its image.

If not mountain lions, these stone fetishes were of bears, wolves, and occasionally a long-tailed unidentified animal called rohona.

In most of these carvings, the heads are clearly delineated, but the bodies may simply taper off to a point rather than being fully formed.

Many men and certainly almost all prominent or important men of the village, and sometimes the women, carried one somewhere on their persons. The smallest figures were either drilled through the back and worn on a thong, or more frequently embedded in a small amount of cornmeal contained

in a very small pouch and suspended about the neck. Others might be worn by young children to protect them from unexpected harm. Frequently one of these images was placed beneath the stacks of corn in the houses to protect them from damage. Some stones of various shapes and kinds were known as awilaonga, mirage makers or magnifying medicine. These stones were said to increase strength, courage, or other attributes. They are very important in certain ceremonies in which they are placed in medicines to increase courage and "make the heart strong." But they can be carried and used for other functions as well. Such a stone was said to have been used by the Hopis when they were pursued by the Navajos. Racing to a nearby cliff, they placed their mirage stone at the base and then quickly climbed the bluff. To the oncoming enemy, the cliff appeared to rise in height to such an extent that the fleeing Hopis could not be reached. After the Navajos had left, the Hopis climbed back down and escaped, taking their stone with them. Within most of the houses in the Hopi villages, there are other fetishes that protect the people from harm or bring great benefit. Much larger than any of the foregoing fetishes, they may be a foot or more in height and usually are adorned with prayer feathers given to them at various times. Cornmeal is regularly offered to them, and sometimes strings of turquoise and shell are draped about them. These fetishes are conceived of as living beings who can sometimes be heard moving about in the rooms where they are kept. Most often they are carved of sandstone or some similar material and might represent a bear with all the strength and power of that animal being drawn upon to protect the house, or a frog that would be expected to bring the moisture necessary for growing corn. Others may be of human-shaped beings, such as one of the Twin War Gods who frequently aid the Hopis in times of trouble. When the Hopi elders gather in their kivas for rituals, they bring out fetishes of even larger size, more elaborate forms with specific sacred purposes. Because of their power, these icons are kept apart from the village and are brought in only for a particular ceremony. Refurbished, repainted where necessary, and garnished with cotton-tied feathers, they carry the prayers of those assembled, and are placed on the altars to lend strength or inherent powers to ensure the efficacy of the ritual. These fetishes, whether of stone or other materials, are guarded closely by a single individual whose duty it is to care for them when they are not in use and to make sure they are present at the proper time during a ceremonial. Navajo stone fetishes serve the same basic purpose as those of most Pueblo people, though the methods employed and the forms used may vary. Stone fetishes are an integral part of the religious paraphernalia carried by medicine men and used by them for maintaining balances between natural powers and mankind, between the normal and the spirit worlds. Proper use of the items in their medicine bags, or jish, restores physical and mental health, offers protection against evil, and can allay most problems that may beset humans. As each ceremony addresses a different need, the specific objects in the medicine bundle may vary widely. Consequently the more ceremonies known to the medicine man, the greater will be the contents of his jish. Among the most frequent items found in the bundle of the medicine man are sticklike cylinders of aragonite that are worked down to the thickness and length of a small finger. These objects are made of a rock called mirage stone, which occurs in manytoned bands of light and dark. A face is usually made on one end of the cylinders by drilling small holes for the eyes and mouth and filling them with black material. The lighter stones indicate females and the darker ones, males. Most often these rods are bound together in pairs with

FETISHES

multicolored wrappings of yarn and a turkey feather. These two human-shaped stones represent the animating forces of life and happiness as conceived in an original world created in beauty. Properly used in curing, they are said to restore the patient to this original state.

Miniature stone carvings of horses, sheep, game, and other things also are kept in the bundles and used in a similar manner. The intent of these "growing stones" is not to animate the small images but to encourage the spirit of life and creation so that the animals or things represented will increase in good condition for the benefit of the individual sponsoring the ceremony. Fetishes of this kind may be made not only of stones such as travertine, agate, alabaster, and jet but also of clay, cottonwood root, or even flowers mixed with meal made from ground beans.

The difficulty of determining what is or is not a fetish is most apparent in the wooden "re-making" dolls of the Navajos. These small carvings are used in ceremonies to cure illnesses, but despite the fact that they are made in human form, there is strong evidence that they may be intended to represent animals. This is not unusual in that all animals are believed to be human in form when they remove their "garments" of fur.

Improper interactions with animals can cause a variety of illnesses that some believe can be cured only by a medicine man who produces the image and then disposes of it. The differences between the Hopis' use of stone fetishes and that of the Navajos is basically one of ownership and rights of use. Among the Navajos, stones of power are Usually the property of medicine men and are more proscribed in their uses. Those of the Hopis have been divided by use and size and are available to nearly everyone. Although there is a burgeoning interest among non-Indians in fetishes of every description, the perception of the nature of these stone images is little understood. Those produced by the Hopis and Navajos do not differ materially in intent from the fetishes of the Zunis.

In this latter pueblo, however, there is a cottage industry that specializes in making small stone animals that range from bears to dinosaurs and are generally referred to as fetishes made specifically for sale.

Neither the Hopis nor the Navajos produce any stone images of this nature for sale to the public. The ones that these two tribes possess are religious artifacts just as are the original stone fetishes at Zuni. Were stone fetishes from the Hopis or Navajos to appear for sale in the Indian art market, they would almost invariably have a tarnished provenience, which ethical collectors would avoid.

Editor's Note: Fetishes are enormously popular in today's market yet information on who makes them, why they are made, and when they are used is not common knowledge. In trying to achieve a balance between providing this information and remaining sensitive to Indian cultures, photographer Jerry Jacka shot mostly prehistoric fetishes. Also permission to photograph the male and female bundles was given to Jacka by a medicine man. Finally, the child's family gave permission to photograph the baby with corn. Jerry Jacka has been providing photographs of American Indian art to Arizona Highways magazine since 1974. He lives in Phoenix.

Phoenix-based Barton Wright is a former scientific director of the San Diego Museum of Man and curator of the Museum of Northern Arizona. He has written numerous books about Indians of the Southwest.

Already a member? Login ».