Discovering How Nature Works

Nature's Secrets

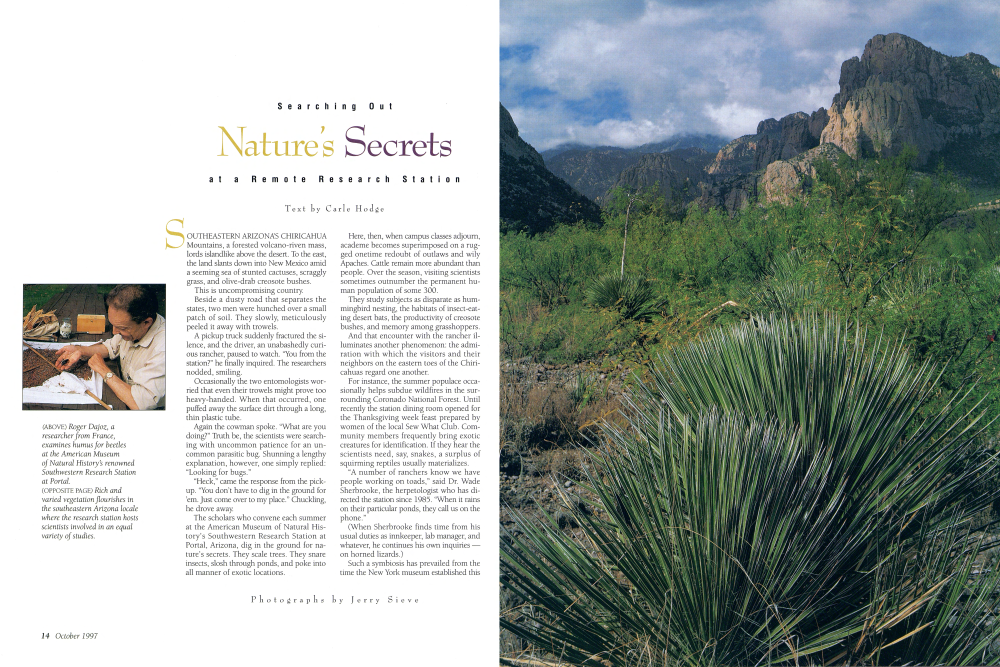

SOUTHEASTERN ARIZONA'S CHIRICAHUA Mountains, a forested volcano-riven mass, lords islandlike above the desert. To the east, the land slants down into New Mexico amid a seeming sea of stunted cactuses, scraggly grass, and olive-drab creosote bushes.

This is uncompromising country. Beside a dusty road that separates the states, two men were hunched over a small patch of soil. They slowly, meticulously peeled it away with trowels.

A pickup truck suddenly fractured the silence, and the driver, an unabashedly curious rancher, paused to watch. "You from the station?" he finally inquired. The researchers nodded, smiling.

Occasionally the two entomologists worried that even their trowels might prove too heavy-handed. When that occurred, one puffed away the surface dirt through a long, thin plastic tube.

Again the cowman spoke. "What are you doing?" Truth be, the scientists were searching with uncommon patience for an uncommon parasitic bug. Shunning a lengthy explanation, however, one simply replied: "Looking for bugs."

"Heck," came the response from the pickup. "You don't have to dig in the ground for 'em. Just come over to my place." Chuckling, he drove away.The scholars who convene each summer at the American Museum of Natural History's Southwestern Research Station at Portal, Arizona, dig in the ground for nature's secrets. They scale trees. They snare insects, slosh through ponds, and poke into all manner of exotic locations.

Here, then, when campus classes adjourn, academe becomes superimposed on a rugged onetime redoubt of outlaws and wily Apaches. Cattle remain more abundant than people. Over the season, visiting scientists sometimes outnumber the permanent human population of some 300.They study subjects as disparate as hummingbird nesting, the habitats of insect-eating desert bats, the productivity of creosote bushes, and memory among grasshoppers.

And that encounter with the rancher illuminates another phenomenon: the admiration with which the visitors and their neighbors on the eastern toes of the Chiricahuas regard one another.

For instance, the summer populace occasionally helps subdue wildfires in the surrounding Coronado National Forest. Until recently the station dining room opened for the Thanksgiving week feast prepared by women of the local Sew What Club. Community members frequently bring exotic creatures for identification. If they hear the scientists need, say, snakes, a surplus of squirming reptiles usually materializes. "A number of ranchers know we have people working on toads," said Dr. Wade Sherbrooke, the herpetologist who has directed the station since 1985. "When it rains on their particular ponds, they call us on the phone.

(When Sherbrooke finds time from his usual duties as innkeeper, lab manager, and whatever, he continues his own inquiries on horned lizards.) Such a symbiosis has prevailed from the time the New York museum established this outpost in 1955. Even earlier, though, the area had been both a scientific magnet and a happy watching ground for birders.

Vladimir Nabokov, the novelist and lepidopterist, spent five weeks nearby in 1953, partly to finish his novel Lolita but mainly to pursue his true passion: butterflies. Although the writing went well, unseasonably cool weather discouraged the butterflies. And after Nabokov dispatched a rattlesnake, his wife insisted they move on.

From the State University of New York at Albany, Jerram Brown, a station regular almost since its inception, studies Mexican jays and found them to be odd birds. Older offspring returned to help their parents feed new generations.

Another of the earlier explorers was Mont Cazier, then an American Museum curator of insects and spiders. Cazier persuaded David Rockefeller, whom he knew as a fellow beetle fancier, to purchase for the institution the 52 acres (later expanded to 90) that would become the research station.

The mile-high land clings to Cave Creek, greened with oak, willow, and ash, and walled by sky-scraping cliffs of gray and salmon-pink rhyolite.

Sublimity aside, the setting also affords a unique amalgam of plants and animals. Of cactuses alone, more than two dozen kinds persist; 74 different mammals (not counting such Mexican strays as ocelots and jaguars) live here, 1,370 species of higher plants and 250 of birds, not to mention red toadstools eight inches across.

Portal, as a result, became famous generations ago as a bird-watching mecca. Enthusiasts make pilgrimages from around the world to glimpse avifauna unique in the nation, among them a coppery-tailed Mexican beauty called the elegant trogan.

But the biologic diversity what Sherbrooke described as "this richness in numbers of species" particularly appeals to professionals. Investigators can delve into the low desert, as well as the Chiricahuas, which soar up almost 10,000 feet, or any of the habitats in between.

"As you drive up the mountain," the New York-born director explained, "you drive through five life zones, or climatic areas. You get exposed to a lot of organisms. This is a place where things mix."

With such a treasure trove, the scholars probably would have kept coming anyway, if in far less numbers. What the museum provides for modest fees are rooms, meals, modern laboratories, and a library. The fees help finance the operation, and field work for the scientists no longer means a crude campsite in the wild. Not surprisingly, these inducements lure specialists bent on a variety of projects. Roger and Aline Dajoz flew from France to collect beetles for comparison with similar species they found in North Africa. They quickly learned a prime time and niche for this endeavor: at night outside the lone bar in nearby Rodeo, New Mexico. When they strung a light there, the beetles appeared as if by legerdemain.

Also on the night shift: a group dispatched from London University by Dr. Richard Tinsley. For more than 10 years, he and his aides have concentrated on waterborne parasites that infest the bladders of spadefoot toads.

One of the Tinsley team, Dr. Karen Tocque, looked that season at aging rates among the amphibians by analyzing the growth rings in their tiny bones.

Because they behave so bizarrely and thrive here spadefoots have long been a favored focus for analysis around Portal. Their sex life, for one thing, is both boisterWhile the British caught toads, Dr. Jan Randall of San Francisco State University listened in the darkness to kangaroo rats. She knew by then that one species, the bannertails, communicates by stomping their feet.

The sound, which she recorded and analyzed with sensitive instruments, reminded Randall of "jungle drums." Each of the little desert rodents drums in a distinctive rhythm she suspects is "an auditory keep-out signal."

For an animal so small they seldom weigh more than five ounces bannertails produce a remarkable racket. One Randall assistant mistook it for the trampling of a nearby deer.

After a wild midsummer night, both the toads and the "k-rats" fell fast asleep before a squad of mycologists mushroom experts set out to search for specimens.

Although most were degreed authorities, such as Dr. Rosalia Vazquez-Estup, a Mexico City professor, they included one seasoned amateur, Robert Chapman. When he

Nature's Secrets

Isn't tracking mushrooms or other fungi, Chapman makes a living "hanging doors" in Sepulveda, California. He wore a T-shirt emblazoned "The Best Little Door House in Town."

The object of the sortie was to learn more about the coevolution of fungi with other plants. At pine-scented Barfoot Park, elevation 8,823 feet, the researchers hit a homer: a forest clearing punctuated with colorful mushrooms.

Meanwhile, back at the station, Diane Wagner, a Princeton Ph.D. candidate, traced the relationship of butterflies with their host plants, and Ken Helms, a graduate stu-dent at Arizona State University, studied the sexual relations among ants.

This was the third year here for the two but the 14th for Jan Randall, the kangaroorat lady. The spell once cast, researchers tend to return, and in some cases to remain.

Founding Director Cazier, who left to become an ASU professor, summered at Por-tal. The museum's Willis Gertsch, perhaps the preeminent spider specialist, retired here. So have others, among them Robert Chew, a desert ecologist from the University of Southern California.

Intelligence feeds upon itself.

A week before our latest visit, Drs. Howard Topoff and Carol Simon left to resume teaching in New York, he at Hunter College, she at City College.

An animal-behavior scientist, Topoff plumbs the secrets of slave-making ants, which evolved in such a way they can no longer survive alone. Raiding became their sole skill. What they do, therefore, is plunder and enslave the pupae of a related species, then the captives end up performing all their captors' chores.

An obvious question is, why don't the slaves rebel against those body-snatchers? Topoff figured that out: They were taken at so early a stage, they know no better.

Simon specializes in lizards. Among other riddles she looked into was why they flick their tongues. At least some, she discovered, use their tongues to detect changes in the chemical environment. That permits them to sense the presence of snakes and possibly other predators. Topoff first came, as a grad student, in1964. That same summer, Simon, from Azusa, California, arrived as a high-school volunteer. Both returned the next year, when she earned her keep as an assistant cook. The two married in 1976 and bought a summer home in Portal two years thereafter.

Beyond this durability of senior scientists, the long-term future of the station seems assured by an unremitting parade of younger, inquisitive minds like those of Princeton's Wagner and ASU's Helms.

One summer, Allison Abell, with a fresh diploma from Yale and a ticket to graduate studies at the University of Chicago, mapped the distribution of spiney lizards. And she paid her way as a kitchen helper, just as Carol Simon did.

No doubt the intellectually curious will continue to uncover insects around Portal, and hark to the thump of kangaroo rats and the siren songs of spadefoots for innumerable summers to come. M Editor's Note: Since this story was written, some of the people have changed professional associations or completed academic goals. Founding Director Mont Cazier passed away.

The Southwestern Research Station (602558-2396) is not geared for guided tours, but it offers room and board to non-scientists when space is available. Reservations are strongly advised.

(OPPOSITE PAGE, TOP TO BOTTOM) Dr. Wade Sherbrooke, the station director, displays some preserved horned lizards. spadefoot toads, which thrive in the area, have been a favorite study subject at the station.

Dr. Jan Randall keeps a firm grip on a kangaroo rat, a tiny creature that holds a big fascination for the scientist. (BELOW) The director's residence sits to the right of the building housing the station's labs and offices.

Already a member? Login ».