The Coronado Epistle

THE LOST CORONADO EPISTLE

Alighting from his exhausted horse, the bone-tired courier saluted young Gen. Francisco Vasquez de Coronado and presented him with a precious packet of letters he had carried all the way from Mexico City to Coronado's encampment along the trail to the mythical seven golden cities of Cibola.

The time was probably December, 1540, or January, 1541, and the place was somewhere in eastern Arizona or western New Mexico. This was no ordinary mail delivery, but one of historic import: The letters were almost certainly the first ever delivered to what is now the United States.

Coronado no doubt read them with feverish interest: a letter from Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza of New Spain, letters from his wife and, most exciting of all, a letter from El Rey, himself, King Charles I of Spain. In it the king gave his royal blessing to Coronado's epic journey of exploration and conquest of the American Southwest.

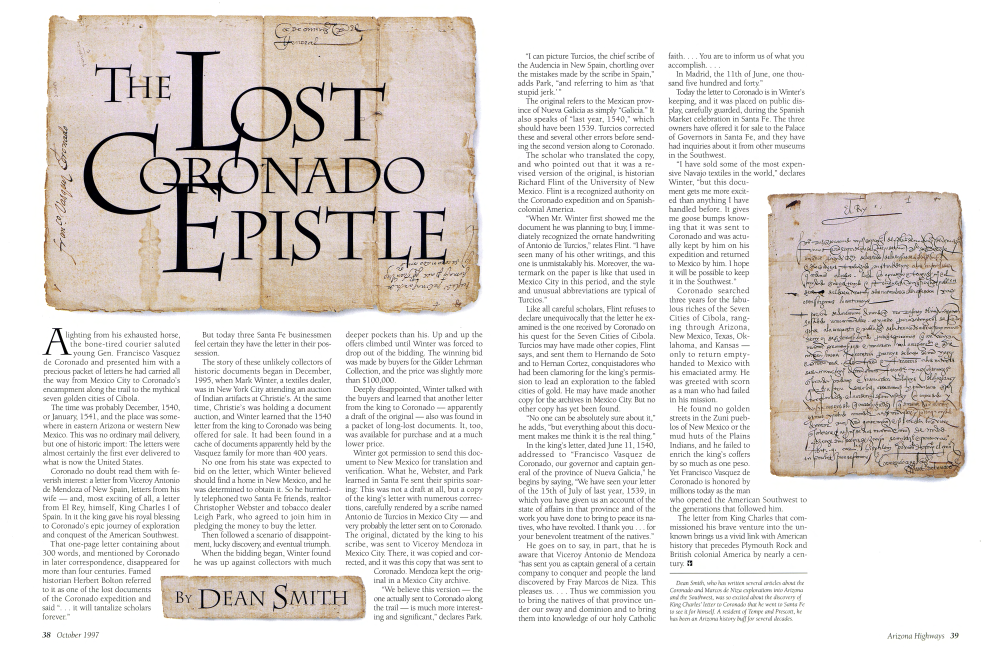

That one-page letter containing about 300 words, and mentioned by Coronado in later correspondence, disappeared for more than four centuries. Famed historian Herbert Bolton referred to it as one of the lost documents of the Coronado expedition and said "... it will tantalize scholars forever."

But today three Santa Fe businessmen feel certain they have the letter in their possession.

The story of these unlikely collectors of historic documents began in December, 1995, when Mark Winter, a textiles dealer, was in New York City attending an auction of Indian artifacts at Christie's. At the same time, Christie's was holding a document auction, and Winter learned that the 1540 letter from the king to Coronado was being offered for sale. It had been found in a cache of documents apparently held by the Vasquez family for more than 400 years.

No one from his state was expected to bid on the letter, which Winter believed should find a home in New Mexico, and he was determined to obtain it. So he hurriedly telephoned two Santa Fe friends, realtor Christopher Webster and tobacco dealer Leigh Park, who agreed to join him in pledging the money to buy the letter.

Then followed a scenario of disappointment, lucky discovery, and eventual triumph. When the bidding began, Winter found he was up against collectors with much deeper pockets than his. Up and up the offers climbed until Winter was forced to drop out of the bidding. The winning bid was made by buyers for the Gilder Lehrman Collection, and the price was slightly more than $100,000.

Deeply disappointed, Winter talked with the buyers and learned that another letter from the king to Coronado apparently a draft of the original also was found in a packet of long-lost documents. It, too, was available for purchase and at a much lower price.

Winter got permission to send this document to New Mexico for translation and verification. What he, Webster, and Park learned in Santa Fe sent their spirits soaring: This was not a draft at all, but a copy of the king's letter with numerous corrections, carefully rendered by a scribe named Antonio de Turcios in Mexico City and very probably the letter sent on to Coronado. The original, dictated by the king to his scribe, was sent to Viceroy Mendoza in Mexico City. There, it was copied and corrected, and it was this copy that was sent to Coronado. Mendoza kept the original in a Mexico City archive.

"We believe this version the one actually sent to Coronado along the trail is much more interesting and significant," declares Park.

BY DEAN SMITH

Already a member? Login ».