Life, Death, and Rebirth of a Fateful Spanish Fort

THE SAN PEDRO RIVER'S TRAGIC SPANISH PRESIDIO TEXT BY SAM NEGRI PHOTOGRAPHS BY RANDY PRENTICE

No arrows. No bullets. Nothing to fear that late fall in 1985. Even the rattlesnakes were away on sabbatical. I had accompanied a young archaeologist named Jack Williams to a barren hillside near Fairbank on the San Pedro River. Someday, Williams said, someone will put a park here so people will know what happened. What happened on that forlorn hillside was this: People died with alarming frequency. Some were hostile Indians, but more were Spanish soldiers. Fear, totally absent during my excursion, was once a major element in the life of soldiers living on this hill. They were trying to finish building the Presidio Santa Cruz de Terrenate, a fortress designed to protect settlers colonizing southern Arizona in 1775-76. The Indians, who considered this land their turf, thought this sort of activity was a very bad idea, and they expressed their displeasure by stealing the Spaniards' horses and stock and killing any human that didn't look like a fellow Indian. If you weren't Indian, you were presumably a Spaniard or some other lifeform that didn't belong. Frankly the idea of a park or a preserve for the crumbling remains of the old fort seemed remote. But as we walked across that hill and Williams described the people who had the misfortune of living at this site, it began to seem a bit more plausible. The events that unfolded there were a reflection of what can happen when two intransigent cultures collide. Few have heard this chapter of American history; the clash occurred so far from the population centers of the East Coast and at a time when Arizona was a long way from becoming a part of the United States.

During this era, when Spain was busy gobbling up the land that eventually would be Arizona and California, colonists back in Massachusetts were knocking over a statue of King George III and setting the American Revolution in motion.

But Arizona, which the Spaniards referred to as terra incognita, was witnessing an entirely different kind of war: a clash between Europeans and a primitive culture. Spain, the cultural cradle that had nurtured Cervantes, Calderon de la Barca, and Lope de Vega, was determined to beat sense (not to mention religion) into the minds and hearts of the Indians.

That idea didn't quite work out at the place called Santa Cruz de Terrenate. In the second half of the 18th century, the Spaniards had three forts in what would later become southern Arizona. There was one at Tubac, another at Tucson, and Terrenate. At Tubac and Tucson, the Spaniards eventually succeeded in imposing their culture on the native inhabitants, which generally meant that more Indians than Spaniards were killed.

But Terrenate was another story.

As he stood amid the scant remains of the presidio, Williams wistfully remarked, "This was not a fun place to be in 1776. The Spaniards came here as conquerors and left as evacuees. I have a feeling there were a lot of deserters from this place because it seems you had a choice of dying here or someplace else."

It took me nearly 10 years to get back to Terrenate after that first visit with Jack Williams, but when I did I was able to walk across the bluff on a wide, well-maintained trail and read a series of plaques that describe what the presidio looked like when it was built.

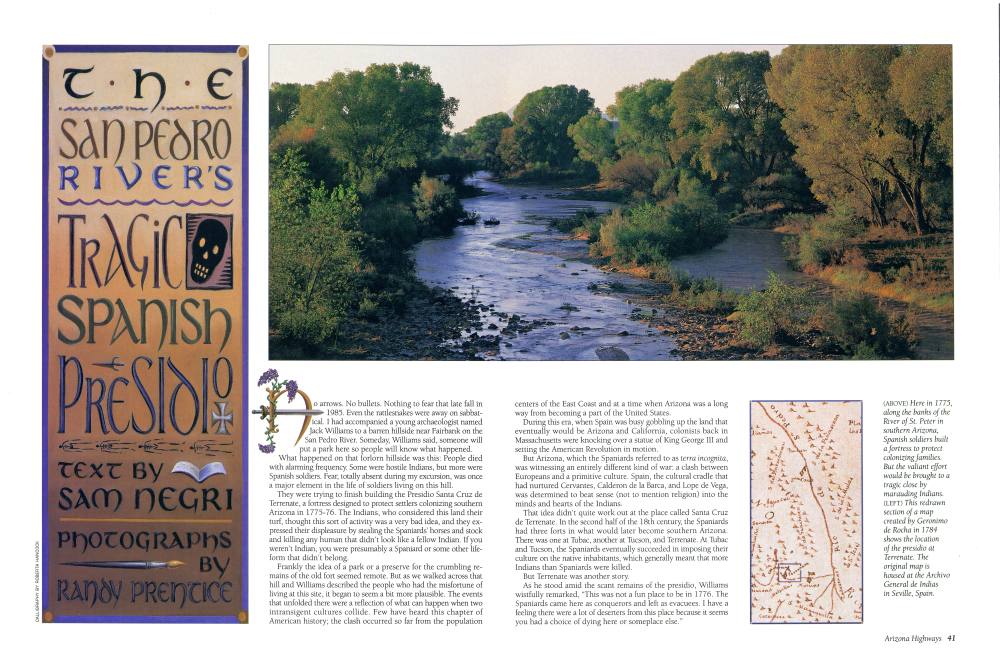

The 1.2-mile trail that meandered to the ruins of the presidio began on Kellar Road, which runs north off State Route 82. The trail is wide and sandy, almost a bridle path. As I headed down a gradual slope toward the San Pedro River, I saw isolated mountain ranges 30 and 50 miles away, their long jagged backs and tawny bulk making them appear like enormous prehistoric creatures hunkered down in the silent desert of southern Arizona.

The presidio that once occupied this hillside was actually a handful of adobe buildings arranged inside a compound surrounded by a wall that was never finished. On a winter day when the temperature was hovering around 70° F, I walked the new trail to see what remained of the presidio ruins I had visited a decade earlier.

The fact that visitors can drive to within a mile of the ruins was a major change since my first visit. Santa Cruz de Terrenate was never a very accessible place. That may explain why anything remains at all. Since it was abandoned as indefensible in 1780, these dried-out presidio ruins have remained unknown to the general public. Occasionally, archaeologists came and attempted to piece together the story of the ill-fated fort and the prehistoric Indian settlement that preceded it on the same site. Treasure hunters also poked in the ruins from time to time hoping to uncover some elusive and valuable relic, but for most of the last 200 years the fortress once known as Terrenate was generally ignored.

The combination of torrential summer rains, blistering winds, and sporadic vandalism would eventually have eradicated the few remaining walls of the old presidio, but serendipity stepped in a few years ago, and the area around and including the site became part of a federal preserve. In 1988 a 40-mile swath of land along the San Pedro River - including a section that snakes by the base of the old presidio was given federal protection and designated the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area.

The Bureau of Land Management, which is responsible for preserving the rare streamside (or riparian) flora and fauna along the San Pedro River, also was interested in protecting the few structural remnants of the area's history, among them the long-deserted presidio near Fairbank. This was particularly good news to Jack Williams, who had spent so many years studying the lives of those who lived and fought at this doomed spot.

In the winter of 1993, the grounds of the presidio were fenced and signs were installed in front of various mounds and broken walls to explain what once was there. Little remained of the gatehouse, which archaeologists think may have been a two-story structure, or the simple chapel, though experts think it lasted a lot longer than the other buildings. Two Franciscan priests were assigned to the chapel at Terrenate, but one was killed en route to his post, and the other asked for retirement soon after his arrival.

Who can blame him? Almost every activity at Terrenate was fraught with danger. To obtain water, settlers at the presidio had to walk down the steep banks of the San Pedro River - not a long walk by ordinary standards but one that was occasionally fatal. Anyone who went for water or set out for nearby fields to tend crops or livestock stood a good chance of being attacked and killed by the hostiles.

The Spaniards, to some extent prisoners of their own customs, had other problems as well. Their clothing, for example, was completely unsuited to either the climate or the terrain of southern Arizona, as a brochure on the presidio ruins notes: "Woolen jackets, breeches and capes, black neckerchiefs, hats, shoes, leggings, leather bandoliers and seven-layer buckskin tunics were the typical outerwear for presidial soldiers. Considering the local temperatures, this amount of clothing probably restricted movement. Attendance records indicate that many residents took leave at every opportunity and often tried to be reassigned at other presidios."

This is, of course, classic understatement. From May to early October, southern Arizona is extremely hot (someone once said cavalry soldiers killed in Arizona were often buried with their blankets so that if they ended up in hell they wouldn't freeze to death). Aside from the heat, the business of maneuvering in the area's rocky mountain ranges, sandy washes, and densely vegetated canyons must have been exhausting in the regalia required of a Spanish dragoon.

were often buried with their blankets so that if they ended up in hell they wouldn't freeze to death). Aside from the heat, the business of maneuvering in the area's rocky mountain ranges, sandy washes, and densely vegetated canyons must have been exhausting in the regalia required of a Spanish dragoon.

But these discomforts would have been minor alongside the ever-present threat of death. The inability of soldiers and settlers to plant and harvest safely also was crucial. As Williams noted, "Soldiers and settlers at the fort were literally starving to death.

About a year after Santa Cruz de Terrenate was abandoned in early 1780, Don Teodoro de Croix, commander of New Spain's northern frontier, listed among the reasons for vacating the presidio: "... the terror instilled in the troops and settlers of the presidio of San Cruz that had seen two captains and more than eighty men perish at the hands of the enemies in the open rolling ground at a short distance from the post, and the incessant attacks which they suffered from the numerous bands of Apaches, who do not permit cultivation of the crops, who surprise the mule trains carrying effects and supplies, who rob the horse herds and put the troops in the situation of not being able to attend their own defense, making them useless for the defense of the province."

Ironically, while Terrenate did not survive at the Fairbank location, it had several life spans at different places in what is now northern Sonora, Mexico, and southern Arizona. Located originally at Terrenate, Sonora, from 1742 to 1775, the presidio was moved to the Fairbank location in 1775 and then to Las Nutrias, Sonora, in 1780. Seven years later, it was moved to its final location, Soamca, Sonora, a border town known now as Santa Cruz.

Today little remains of Arizona's Terrenate except a scattering of adobe walls on a lonely hillside, and yet it is the best preserved royal regulation presidio west of Texas.

"The fascinating thing about this particular place," observed Jack Williams, "is that the terrain around it probably doesn't look much different today than it did in 1780. There isn't much down here except the surrounding mountains and valleys."

WHEN YOU GO

The presidio is open year-round. Take Interstate Route 10 east from Tucson to State Route 90; go south 20 miles to State 82; turn east and proceed nine miles to Kellar Road; then head north two miles to the BLM parking lot. A 1.2-mile hiking trail leads to the ruins. Respect the ruins and avoid any actions that will damage them. San Pedro House, which displays a model of the presidio, is a restored historic ranch house serving now as a bookstore-gift shop. For directions to San Pedro House and information about hiking and birding, contact San Pedro Conservation Area Office, 1763 Paseo San Luis, Sierra Vista, AZ 85635; (520) 458-3559.

Already a member? Login ».