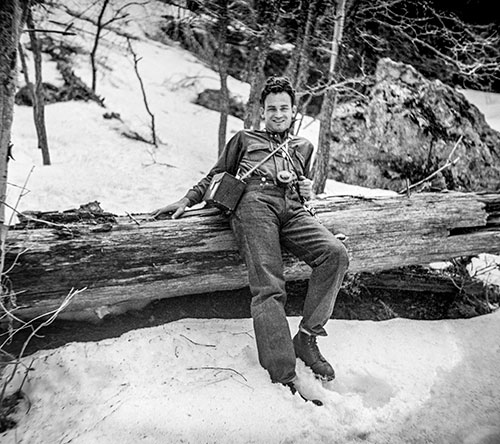

Barry Goldwater looks positively blissful. It’s the summer of 1940, and 31-year-old Barry is deep into a journey along the Colorado River that will make him just the 73rd person to travel through the Grand Canyon by boat.

Barry is virtually unrecognizable in the photograph. Wearing a T-shirt, he gazes into the distance, his eyes alive and his smile serene. The high forehead appears familiar, but Barry’s trademark jutting jaw is concealed by a thick, dark beard, the kind men grow when the closest mirrors are miles away and wives won’t be seen for several weeks more.

Barry had left behind his wife, Peggy, in San Diego that July with the couple’s three small children, including son Michael, born just four months earlier. Peggy didn’t want her husband to go on the trip, and Barry confessed a measure of guilt at temporarily abandoning his young family. But he also couldn’t resist the opportunity to challenge the fabled rapids with pioneering river runner Norman Nevills, to satisfy what he described as a “long smoldering desire to make the trip down the Colorado River in an open boat.” He dubbed it “riveritis.”

Crafted by Nevills from half-inch plywood and designed to navigate the Colorado in both its most limpid and its most turbulent extremes, the flat-bottomed boats, which Barry helped build, measured 16 feet long and spanned 6 feet at their widest. On either side of the cockpit, hatch lids, secured tightly by refrigerator handles, protected waterproof compartments, an important consideration for Barry Goldwater. Because he wasn’t traveling light.

As a small boy, Barry discovered a Kodak Brownie box camera that belonged to his mother, Josephine. Ever since, he had loved photography. He combined photography, as well as such emerging technologies of his youth as aviation and radio, with an abiding fascination for his native Arizona. Long before embarking on the river trip, Barry set out to visit and photograph remote parts of the state, bringing together an artist’s eye and an anthropologist’s commitment to record his homeland’s ancient cultures and timeless, yet fragile landscapes.

So, having graduated from the Brownie to more sophisticated cameras — first a 2¼ Eastman Kodak Reflex (a Christmas gift from Peggy in 1934), later a Graflex 4x5 and a Rolleiflex 3.5 — Barry did what he could to protect his gear and film from the silt-laden waters of a still-undammed Colorado, the river Barry and many others described as “too thick to drink and too thin to plow.”

In addition to his still-photography equipment, Barry took along a movie camera, and over the course of the trip, he shot roughly 3,000 feet of footage that would indirectly help him launch the long political career that led to five terms as a United States senator and to the brink of the presidency in 1964.

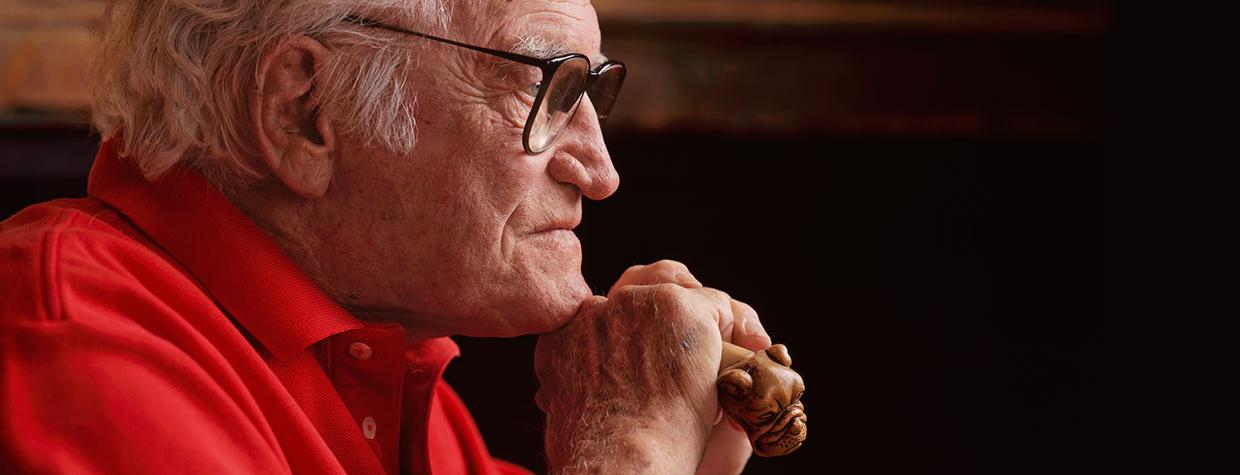

Barry was both reviled and revered in his time, sometimes by the very same people. He’s considered the father of modern conservatism, yet he embraced positions that today would qualify him as liberal. A maverick before that term came into political vogue, he lived the authentic Western life of self-reliance and rugged adventure that Ronald Reagan mostly played on screen.

Through it all, photography and Arizona itself were constants. In the aftermath of his loss in the 1964 presidential race and his departure from the Senate, Barry found solace in the land that he once likened to 114,000 square miles of heaven that God had brought down to Earth.

At a post-election press conference, he declared, “I’ve got heaven to come home to. Not everybody has.”

As if in a hurry to get on with things, Barry Goldwater was born on the very first day of 1909. Three years older than Arizona itself, he watched his mother, known as “Mun,” sew two new stars onto the American flag after New Mexico and Arizona earned admission to the union. He came of age during a time when Arizona sat poised between its Old West traditions and the inevitable onslaught of modernity.

Barry was Arizona royalty. The nephew of a prominent politician, he later ran the family department store, which grew out of a business that his grandfather Michael, a Jewish immigrant from Poland, first operated in the lower Colorado River gold-mining boomtown of Gila City in the 1860s.

Phoenix nearly tripled in size during the first 10 years of Barry’s life, but even by 1920, fewer than 30,000 people lived in the community. Barry recalled exploring the slopes of South Mountain and Camelback Mountain, and learning to swim in the Salt River. He ran with a group of boys dubbed the Center Street Gang, who found the perfect terrain for their hijinks in the growing desert town and the wilds surrounding it.

His father, Baron, focused on the store and showed little inclination for outdoor adventure, so it was left to Mun, Illinois born and with a frontier woman’s pluck, to introduce her three children to the untamed glories of Arizona.

“It all started with his mother,” says Barry’s son Michael. “She was a wonderful woman — a deadeye rifle shot who fished, hunted and camped.”

Young Barry quickly grew comfortable sleeping beneath the stars on the family’s many camping trips. They traveled to the Hopi and Navajo lands of Northern Arizona, and Mun drove out from Yuma and into California on the Plank Road, a route constructed of sections of wood laid across the dunes. According to Barry’s daughter Joanne, Mun also instilled patriotic values in her children, once a week taking them over to Scottsdale’s Indian School Park to salute the flag when it was lowered in the evening.

During the family’s travels around Arizona, Barry developed a special passion for the Colorado River: “By the time I was a rather large boy I had seen the Colorado from practically every vantage point in Arizona, from the bottom of the Grand Canyon to the broad expanse of water below Yuma.”

If at best an apathetic student, Barry pursued those things that captured his imagination with a passion that lasted a lifetime. An inveterate tinkerer with a deft mechanical touch, he began learning about radios at age 11, after his father gave him a crystal receiver set. Barry boasted in a 1923 letter to none other than Thomas A. Edison that he had “studied electricity since I was a little kid” and operated a 10-watt radio station.

By 13, Barry had helped set up KFDA, Arizona’s first commercial radio transmitter.

He traced his interest in aviation to a first glimpse of the planes at the 1917 Arizona State Fair, where wing walkers performed and pilots put their primitive aircraft through daring stunts. When he was college age in 1930, and without seeking his parents’ permission, Barry began sneaking out of the house early in the morning to take flying lessons. After Mun found out, she wasn’t angry; she only wished that he had let her know, so she too could have learned to fly.

Barry would eventually pilot an estimated 255 aircraft, from pokey C-54 cargo planes — which he took across the Himalayas between China, Burma and India as a “Hump flyer” during World War II — to supersonic F-16 fighters. (Serving as Senate Armed Services Committee chairman had its perks.)

The world looks different from above, and flying gave Barry a new perspective on his native land — one that ultimately influenced his photography. At a time when many Arizona roads remained primitive tracks (son Michael tells of one trip between Phoenix and Prescott that took 17 hours because of 13 flat tires), flying also gave Barry quick access to otherwise remote parts of Arizona that he was determined to photograph. He would glide low over the land, searching for unmapped features — arches, natural bridges and cliff dwellings — that he could then return to and shoot.

In 1935, Peggy arranged a small ownership stake in Rainbow Lodge, the trading post and base camp that opened in 1924 for tourists seeking to visit the 275-foot-wide Rainbow Bridge. In those pre-Glen Canyon Dam days, there was no Lake Powell for easy water passage to the formation in Southern Utah, so a 14-mile-long trail was built to connect the lodge and the bridge.

One afternoon, while scouting locations near the head of the trail, Barry ran into a fellow photographer: a shorter man, several years older, with distinctive sleepy eyes and a puckish grin. This was not just any photographer, but Ansel Adams, who recalled the chance encounter that led to a lifelong friendship with Barry: “I met a young man who was obviously pursuing photography, as I was, and with obvious fervor. He introduced himself as Barry Goldwater of Phoenix.”

The two shared a reverence for Edward Weston, whom Barry lauded “as the purest of them all” for images that he said attempted to convey “the very substance and quintessence of the thing itself.” Barry would follow Weston’s inspiration, using direct focus and slow film and shutter speeds while relying on the Arizona sun, which he softened with a yellow filter.

On that day, Barry helped Adams find the easiest route down to Rainbow Bridge, and the two men compared equipment and talked photography. Over the years of their friendship, Barry shared his deep knowledge of Arizona’s places and the ways of its Native people, giving the legendary photographer an invaluable understanding of the state. In turn, Adams offered insights into photographic technique and the secrets of the darkroom, enhancing the processing skills that Barry had first learned from Phoenix portrait photographer Tom Bates.

Barry originally used his home’s kitchen sink as his darkroom — much to Peggy’s dismay, because she couldn’t stand the smell of the chemicals. He eventually established a much more professional setup and was meticulous in his photographic routine.

“The first and best advice I received when I began this hobby was to stay with one film and one developer,” he wrote. “There have been temptations to wander, but using the same materials has made my work much easier.” He also created an elaborate filing system, indexed by subject and cross-referenced with 8x10 prints, to keep track of his estimated 15,000 negatives.

While Barry was overseas during World War II, Peggy surprised him by purchasing half-ownership in Rainbow Lodge for her husband. He cut a 2,000-foot landing strip, shortening the travel time from Phoenix to two hours or less, and used the lodge as a base for excursions into Navajo Country and some of the nation’s least-explored terrain.

Like his mother, Barry was determined to introduce his own children to Arizona. According to Michael: “We would be in grade school, and he would say, ‘OK, tell your teachers you have something important to do and you won’t be back for a week.’ And we’d go out on a camping trip. One year, he took 25 YMCA boys and me and my cousin and brother down part of the Colorado River, from Hite’s Landing to Lees Ferry. I was 11 or 12 years old.”

In a television interview, Barry’s son Barry Jr. said: “He dragged us all over the state. We walked all over every monument, every reservation, every mountain. Every gully, we’ve been in. And every night, we’d camp out. He taught us how to light a fire, how to survive. How to camp out and keep warm.”

The family would set out in the “Green Dragon,” the Chevrolet panel truck they used for camping trips around the state — traveling into the borderlands, along the Mogollon Rim and up to the San Francisco Peaks. Barry loved peanut butter, and for more substantial meals, he’d prepare a gravy that he poured over everything from Dutch-oven biscuits to Spam.

“One night in the fall,” Joanne recalls, “we were camping out on the San Francisco Peaks, near the ski run. It was family and friends, and after dinner, we were all settled into our sleeping bags. Then, in the middle of the night, I started hearing bells and braying. Dad got up and shouted, ‘Everybody into the truck! Get into the truck!’ It was a whole huge herd of sheep roaming through the hills and coming right into camp. We had to grab our bags and waited up in the truck until the sheep all passed through. Or they would have trampled right on over us.”

To reach Rainbow Lodge, the family sometimes flew, but Joanne also remembers drives in the Green Dragon when, after passing Tuba City and Inscription House, they left established roads and followed wagon wheel tracks etched in the rock. Barry himself said some of the roads he traveled were so bad that even the sheep wouldn’t use them.

“It was a true adventure,” says Joanne, who was around 12 the first time she made the trip. “That was a pretty desolate area up there on the border with Utah, and it was hard to get to. But the lodge had the cutest little sleeping houses, just big enough for a bed and a sink. They’d feed us in the lodge and people would saddle up to go to the bridge, but some of us walked down. It was a long way, maybe 14 miles. The very first time we got to see the bridge, it was just so awesome. We loved to go out with Dad. He sure showed us Arizona. His Arizona. It was wonderful.”

In August 1951, a fire destroyed most of Rainbow Lodge. After learning of the blaze, Barry flew from Phoenix to Navajo Mountain, passing over the Grand Canyon to show off the gorge to his friend Charles Ray. Looking to the left, Barry noticed what he thought might be a previously undiscovered arch in Nankoweap Canyon. Heading home, he returned to the location, but in the afternoon light, he could no longer locate the formation.

A year later, Barry again glimpsed the arch from the air. After identifying it a third time during another flight, he decided to embark on a river trip in 1953 to find the span. But by then, he was serving as U.S. senator from Arizona, and the demands of his duties in Washington prevented him from traveling down the Colorado.

Barry came up with a solution: A friend, Bob Gilbreath, owned a helicopter company, and Barry asked him to haul one of his aircraft to Cameron. From there, the pair would fly to the bottom of the Canyon, then hike to the arch. With the sun rising on what Barry described as a clear morning, Gilbreath flew about 300 feet above the landscape, passing over the Little Colorado River Gorge and its junction with the main Canyon, before setting down on the south bank of Nankoweap Creek around 8 a.m.

Despite a few miscalculations — most notably, failing to identify a waterfall that blocked their passage, forcing the two men to backtrack — around 1:30 p.m., Barry and Gilbreath reached a point that offered a complete view of the limestone arch, 200 feet wide and equally tall. It was the culmination of a quest that had begun four years earlier.

“By then,” Barry wrote, “I was exhausted, and every muscle in my body ached, but a great peace and calmness came over me as I realized that here at the end of this arduous trail was that which I had been seeking.

“I sat there and wondered if any other white man had looked upon this thing from such a close vantage point. I suspected that Indians in the past had traveled up here because we found pottery down below, and because we knew that Indians at one time lived at the mouth of Nankoweap. None of the usual evidence of man’s visits, however — tin cans, empty cartons and the like — disturbed the cool calmness of this bit of God’s handiwork.”

Following Barry’s suggestion, the formation now is named Kolb Arch to honor Ellsworth and Emery Kolb, the brothers who operated a photo studio on the South Rim and in 1911 filmed the first motion pictures of the Colorado River’s rapids in the Grand Canyon.

In 1916, when he was just 7, Barry persuaded John Rinker Kibbey, an architect and family friend, to let the young boy accompany him on a trip to the Hopi mesas. Barry recalled that Kibbey, one of the country’s first major collectors of kachinas, put up with his endless questions and bought a 24-inch Mudhead Kachina figure. The price: $3.

Looking back, Barry believed the trip left a lasting impression, helping establish his lifelong connection to the Colorado River: “In a vague, symbolic way, it was for me almost a return to an ancestral homeland. Streams heading in Tusayan washes flow out from Black Mesa, which is Hopi Country, onto the barren northern plateau, eventually reaching the Little Colorado River, which then joins its mother stream, the Colorado River.

“Lower on down on the Colorado, at La Paz and Ehrenberg, my grandfather ‘Big Mike’ Goldwater had established his first stores in Arizona. Somehow I have always felt a close association with the Colorado and its drainage basin within my native state. This feeling of kinship with the Colorado River country played a significant role in interesting me in the people and artifacts of the Black Mesa country.”

The trip also inspired Barry’s fascination with Arizona’s Native American cultures. He eventually began his own kachina collection. Then, after World War II, he cleared out his savings account and purchased Kibbey’s figures for $1,200. Over the years, the combined collection, which spans a period from the late 1800s to the 1960s, grew to 437 kachinas before Barry donated the pieces to Phoenix’s Heard Museum while running for president in 1964.

“It’s a tremendously important collection,” says Ann Marshall, director of research at the Heard. “They’re fascinating pieces, really, and remain a critical part of the Heard’s collection. Some of them come from a time almost before kachina dolls were carved for sale. They go through all of the different phases of carving, and some are quite unique in terms of their styles. You can pick out many pieces that are incredibly special.”

For all the artistic value, Marshall says, the collection is most notable for its comprehensiveness, in part because Barry commissioned Oswald White Bear Fredericks, a prominent carver, to create 90 additional dolls. She says those figures fill in gaps and allow the museum to portray the full range of kachina ceremonies.

In other words, Barry assembled the collection with an anthropologist’s eye. “It speaks to Goldwater’s understanding that this was a subject of great breadth and complexity,” Marshall says. “He wasn’t narrow; he was truly trying to get something that gave a picture of the incredible importance of these carvings in Hopi culture.”

Barry adopted a similar approach with his photographs of Native American cultures. “I’ve shot a lot of landscapes, but I’m proudest of my Indian photography,” he said. “I think I’ve got as good a recording of the Indians of Arizona as has ever been done — every tribe, and parts of tribes that hardly anyone’s ever heard of.”

There are many photographs of Hopis and Navajos, of course, but also pictures of Tohono O’odhams, Apaches, Hualapais and Chemehuevis, a Colorado River tribe. Perhaps most notable was his image of a pair of Navajo girls herding sheep in the snow near Rainbow Lodge. That photograph was featured on the cover of the December 1946 issue of Arizona Highways, an issue that became the first nationally circulated consumer magazine to be published in all color, from cover to cover.

Barry was drawn to the Native people of Arizona, but he didn’t merely parachute onto tribal lands, then leave once he found the photographs he was seeking. As historian Evelyn

S. Cooper wrote in The Eyes of His Soul: The Visual Legacy of Barry M. Goldwater, Master Photographer: “The knowledge behind their evident magic took a lifetime to acquire.” Barry took an ongoing interest in the communities. After a major snowstorm in 1947, he airlifted medicine and food to the Hopi mesas, and he would fly in from Phoenix to help after hearing of emergencies over his shortwave radio.

“He ate Indian food, hunted by their methods, slept in their homes, honored their traditions and showed them the respect of learning words from their languages,” Cooper wrote. “More than pretty photographs, he created intimate portraits of people, practices and rituals, many of which were fast falling through the hourglass of history.”

And when all else failed, he paid the going rate of $1 to shoot someone’s portrait.

There were complexities in his relations with Arizona’s Native Americans, especially after Barry became senator and advocated for the Hopis in a series of ongoing land disputes with the Navajos. Barry had also belonged to the Smoki People, a group of non-Indian men in Prescott who would dress as Native Americans and perform sacred ceremonial dances. The members, including Barry, saw the group’s activities as a way to honor and preserve traditions by giving the public a chance to witness rituals that would otherwise be off-limits to outsiders.

But many Hopis considered the Smokis’ performances to be sacrilegious. And good intentions notwithstanding, in the age of social media, a photograph from that time of a wig-wearing senator performing a dance, his body painted red and clad in a traditional costume, would be the stuff of a political consultant’s nightmares.

During the 1940 trip through the Grand Canyon, Barry kept a diary, maintaining a log of weather and river flows and recording his impressions: “Hot as hell, 110°; no shade, no clouds. … Hottest day yet, 120°. … God-awful hot.”

Barry’s nearly seven-week journey had much more in common with one of John Wesley Powell’s expeditions than with today’s pampered, catered Canyon outings in motorized pontoon rafts. Barry’s group wrecked boats, flipped boats and hauled boats off the rocks. They soaked their gear and battled sun, wind, water, sand and bugs along the way.

At times, Barry sounds absolutely miserable, even while his sense of humor remains intact: “Last night was one of those nights when God makes up his mind. He is going to be mean about it. First we were afflicted with swarms of damned May flies. They live only about twenty-four hours, but that is too long. … A breeze came up and blew them away; then the breezes turned into a gale, and before you could wink, we were almost blown away. Sand swirled in copious quantities; and my ears, mouth and eyes soon were filled with grit.”

You also get the sense that he didn’t want to be anywhere else in the world. Barry made photographs of clouds billowing high over the ramparts of Marble Canyon, and below Lava Falls, he captured fluted granite walls that look like wax melting into the Colorado. Near Marble Canyon Lodge, he left the river to photograph a Navajo woman weaving a rug while her daughters carded and spun wool.

Upon first crossing into Arizona from Utah, Barry wrote, “I noticed immediately a more bracing quality in the air; a clearer, bluer sky; a more buoyant note in the song of the birds; a snap and sparkle in the air that only Arizona air has, and I said to myself, without reference to a map, that we were now home.”

Barry kept the oars from the trip and soon put together a 29-minute color film of the journey. By plane and automobile, he barnstormed Arizona to screen the movie and deliver a lecture without notes. With showings from Window Rock to Parker, he figured he covered 4,330 miles in the state.

“What better way is there to see Arizona than by traveling around to towns like these?” Barry explained. “The long quiet desert between Phoenix and Yuma, the green fields on the

way to Tucson, the rolling hills to Wickenburg, and the mountains on the way to Prescott and Window Rock ... all of these things have been the reward for the work it has taken to give the show.”

The Arizona Republic wrote that Barry “told in simple and unhurried style the thrills, chills and spills of that experience.” The Casa Grande Dispatch touted him as a “daring amateur adventurer and sportsman” and the film as “one of the outstanding hits of the year,” thanks to its “color pictures of the swirling gorges of the Colorado River and the color fantasies of its dizzy walls, along with a narrative of the adventures and experiences of the daring group of half a dozen men and two women.”

By April 1941, Barry estimated that, at a time when Arizona had a population of just 499,000, audiences totaling 20,000 had attended 52 showings. That’s 4 percent of the population — the rough equivalent of 280,000 people in today’s Arizona.

Barry was already a prominent businessman thanks to his family’s department store, but the screenings further raised his profile and helped him define what might now be called his “personal brand” in a time long before television and social media. That wasn’t his intent. But Barry enjoyed unmatched name recognition across Arizona, and in 1952, after launching his political career on the Phoenix City Council, he made the leap to the United States Senate.

As a senator, Barry’s love of Arizona’s unspoiled places sometimes conflicted with his belief in free enterprise and what he saw as his responsibilities to his constituents. In 1957, he introduced legislation to expand Grand Canyon National Park, but he also voted against the Wilderness Act of 1964. He pushed for wilderness designation for Aravaipa Canyon, and while out of the Senate for four years after his 1964 presidential loss, he fought to protect Camelback Mountain from rampant development.

Despite often saying that if he had a mistress, it would be the Grand Canyon, Barry advocated for the construction of Glen Canyon Dam, which inundated vast areas he had explored on his 1940 trip. The dam not only changed the rafting experience, but also altered the flow and composition of the Colorado River and the ecology of the Canyon’s depths.

Barry was a major booster of federal reclamation projects. For many years, he believed Lake Powell was the most beautiful lake in the world and lauded the visitor opportunities and economic growth it created. But from the ground and from the air, Barry couldn’t miss the changes that came to Arizona as the state grew: “While I am a great believer in the free competitive enterprise system and all that it entails, I am an even stronger believer in the right of our people to live in a clean and pollution-free environment.”

After observing the impacts of visitors to Lake Powell, he lamented that “we are destroying one of the most delightful places in the world.” By 1976, Barry concluded that his vote for the dam was the most regrettable decision of his political career. As he said in a 1994 oral-history interview with Grand Canyon River Guides, “I started out in favor of the dams; I wound up opposed to them.”

He was not without his contradictions, this man who wrote of the Grand Canyon in the deepest spiritual terms, yet reveled in the memory of arranging for five F-100 Super Sabre jets to fly over the Canyon and set off sonic booms to challenge reports that supersonic aircraft were touching off landslides: “So they came roaring down that canyon, ba-boom, boom, boom, boom! Not one pebble moved.”

In 1993, five years before his death, Barry was asked in a CNN interview how he would want others to remember him. He replied, “As an honest man who tried his damnedest.”