Ted DeGrazia has been called both a genius and a madman. He wasn’t the only one. Edvard Munch, Paul Gauguin and Michelangelo were all thought to be teetering somewhere on the spectrum between genius and madness. And so was Vincent van Gogh, who once said, “I put my heart and my soul into my work, and have lost my mind in the process.”

Mr. DeGrazia never lost his mind, but he certainly displayed some curious behavior. In 1976, he burned a pile of his paintings worth approximately $1.5 million — when adjusted for inflation, that would be about $8.3 million today. It was a protest against the estate tax. There are many stories about his antics, but none of them slowed the juggernaut. He still became a beloved millionaire. And, like the other madmen with palette knives and paintbrushes, we’re still talking about him — more than four decades after his death.

Of all the contributors to Arizona Highways, no one fills the mailbag like Ted DeGrazia. It’s not even close. That’s because his artwork was ubiquitous in the 1960s and ’70s. Like microwaves, tube socks and vinyl records (the first time around), his artwork found its way into millions of homes in dozens of countries, exposing Baby Boomers — and their children and grandchildren — to something they’d never forget.

“As a child,” Erin Estes Newman says, “I was lucky to visit his Gallery in the Sun a few times while staying with my grandma in Tucson. She loved his work, and it holds a special place in my heart, too — we still have tons of DeGrazia everything!”

“I became a DeGrazia fan while a student at Northern Arizona University in the early 1970s,” Jan Strobel Schumacher says. “I still love his work.”

Gina Valentino is an admirer, too. “I had the DeGrazia greeting card pack,” she says. “My grandmother had an original DeGrazia hanging in her bedroom in Cleveland back in the day. I still have a set of the DeGrazia refrigerator magnets.”

Greeting cards, refrigerator magnets … his artwork was reproduced on just about anything with a flat surface. Or any surface, really.

“His flow of creativity became at times a torrent of prints and plaques and cards and serigraphs and stained glass and statuettes, etc.,” said Gary Avey, our former editor. “Virtually every means of reproduction has been employed to spread the creations of DeGrazia throughout the world. A massive dissemination, which prompted the critics to cry over and over again that Ted was merely commercial and exploitative. He was, they said, certainly not a serious artist.”

In addition to the slagging he took for peddling his wares, he was criticized for the quality of his art. But it didn’t keep him up at night. “In spite of the criticism,” he said, “I stuck to my own style and painted as I wanted to paint, expressing what I felt inside.”

That’s a lesson he learned from Ross Santee, a longtime contributing artist to this magazine who would become one of Mr. DeGrazia’s most influential mentors. “When you put your name on any work,” Mr. Santee told the young artist, “that is a piece of your hide up there for anyone to see and like or hate. So, only paint and show what is really you, and then accept what the public says. Ignore the critics and professors. They can’t sell, so they gripe.”

He would get other advice along the way. “Only paint what you know intimately,” said José Clemente Orozco, the renowned muralist who had mentored Mr. DeGrazia in Mexico City. Another mentor, Diego Rivera — one of Mexico’s most famous artists — taught him to study a scene and then paint it later, away from the site.

“I never sketch,” Mr. DeGrazia said. “I’m not the kind of painter who puts on a beret, a smock and sets up an easel. I try to retain what I see. And if I don’t remember it, then it isn’t worth putting down.”

And so, his course was set. And he worked hard to get where he was going. “He is a serious painter,” Editor Raymond Carlson wrote in our March 1949 issue, “desperately trying to express himself in art and color. He works with a feverish concentration, using the palette knife with wild abandon, translating his emotions into rich, striking colors.”

It’s the colors that resonate with so many of his disciples. And it’s what most of us remember from our grandmothers’ kitchens. The cadmium yellows. The cerulean blues. The phthalo greens.

“From childhood I have been interested in color,” Mr. DeGrazia said. “Often I went on long hikes with my father. We always came home with our pockets filled with colored minerals. These rocks I crushed with a hammer for color. Color fascinated me. Sometimes we found clay, which I modeled and baked in the kitchen oven. My mother tells me how I would get her kitchen full of mud and how I always wanted to bake my figures in the oven when she was baking bread. In the little mining town of Morenci, where I grew up, I found much color. It made a deep impression on me.”

And so did religion.

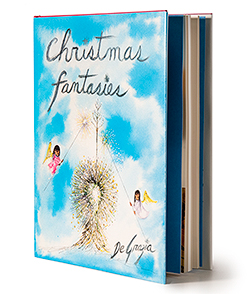

“I’m not a churchgoing man,” he said, “but I am a religious man, and perhaps religious only within me.” That may have been his perception, but his spirituality poured out, like monsoon rain from the heavens, and became a primary theme of his paintings. Twenty-nine of them are collected in Christmas Fantasies, a beautiful book that was first published in 1977.

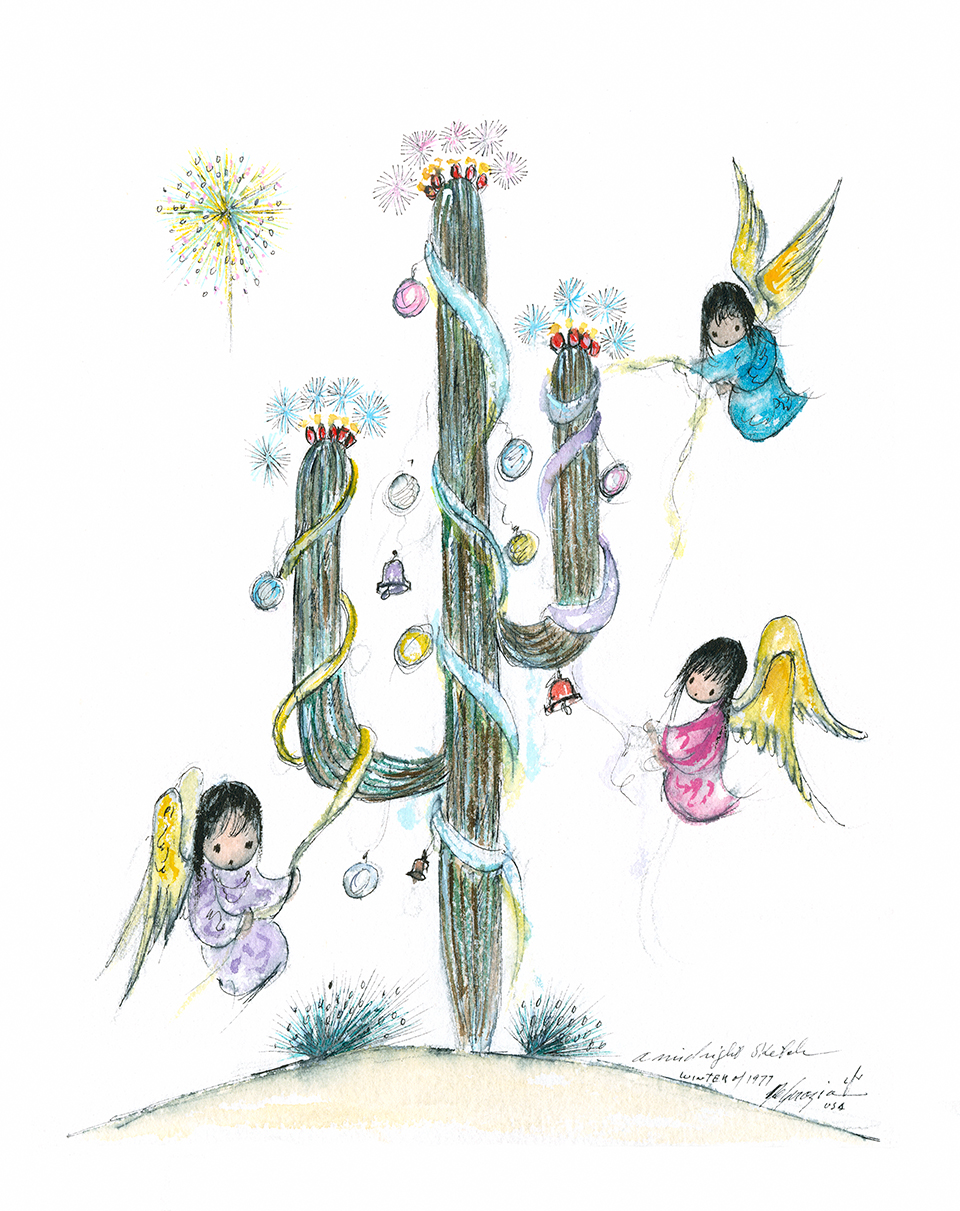

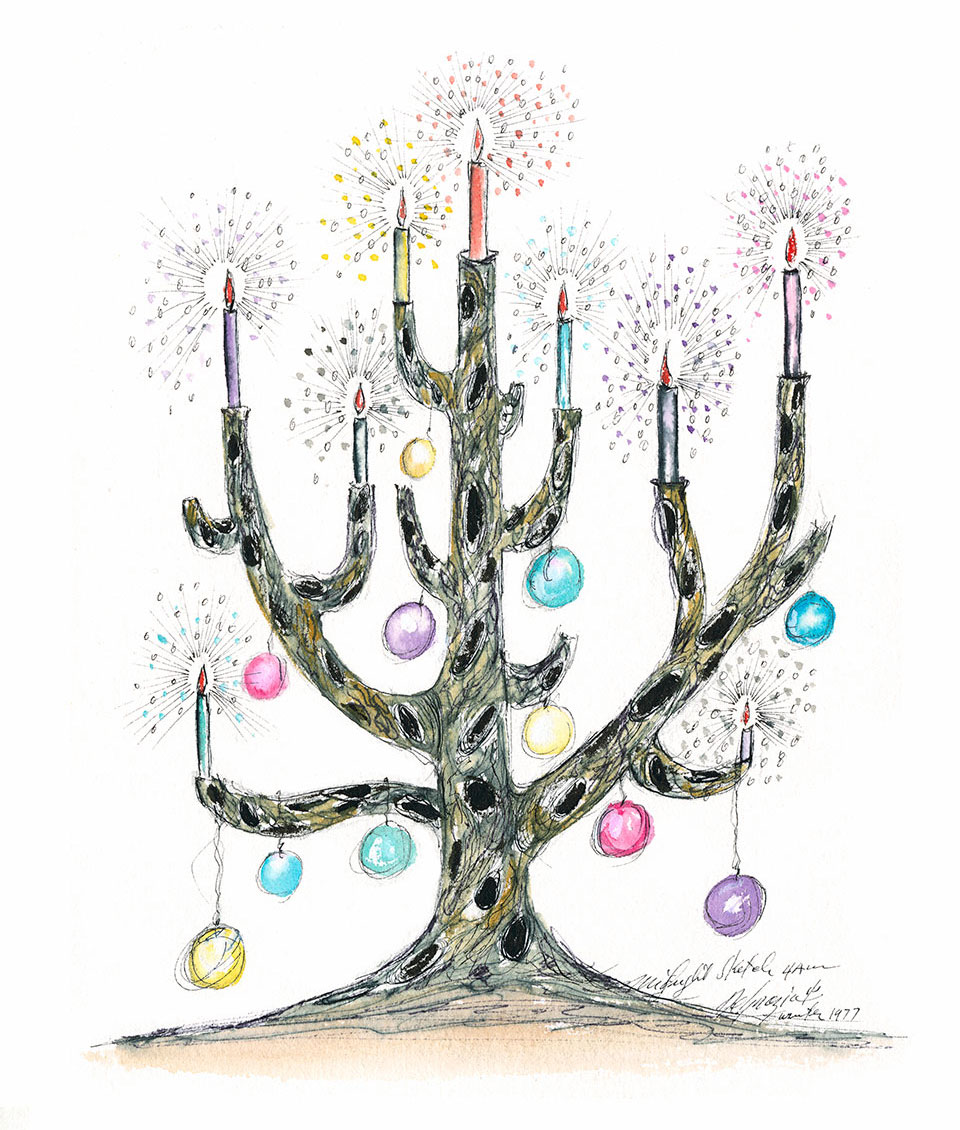

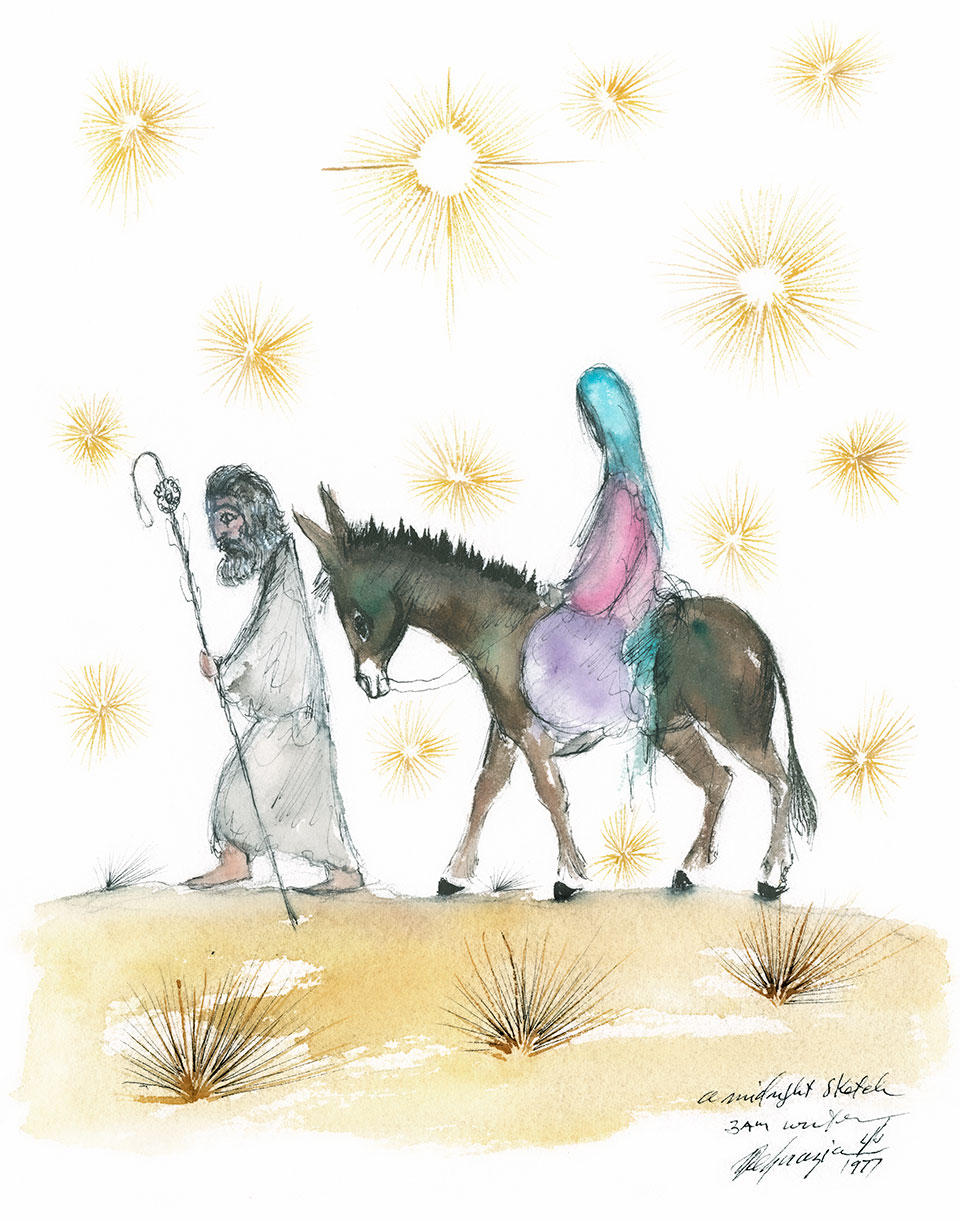

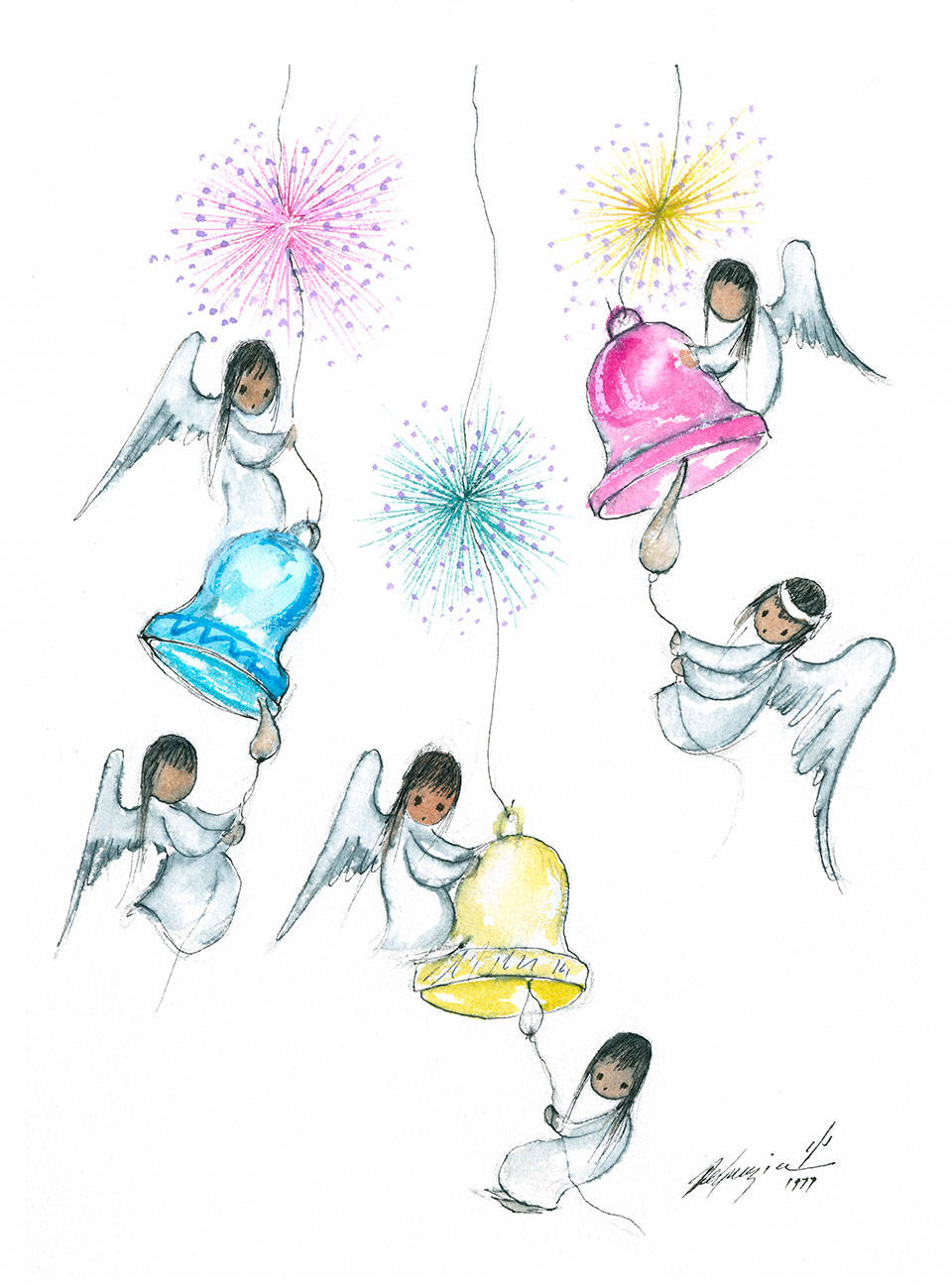

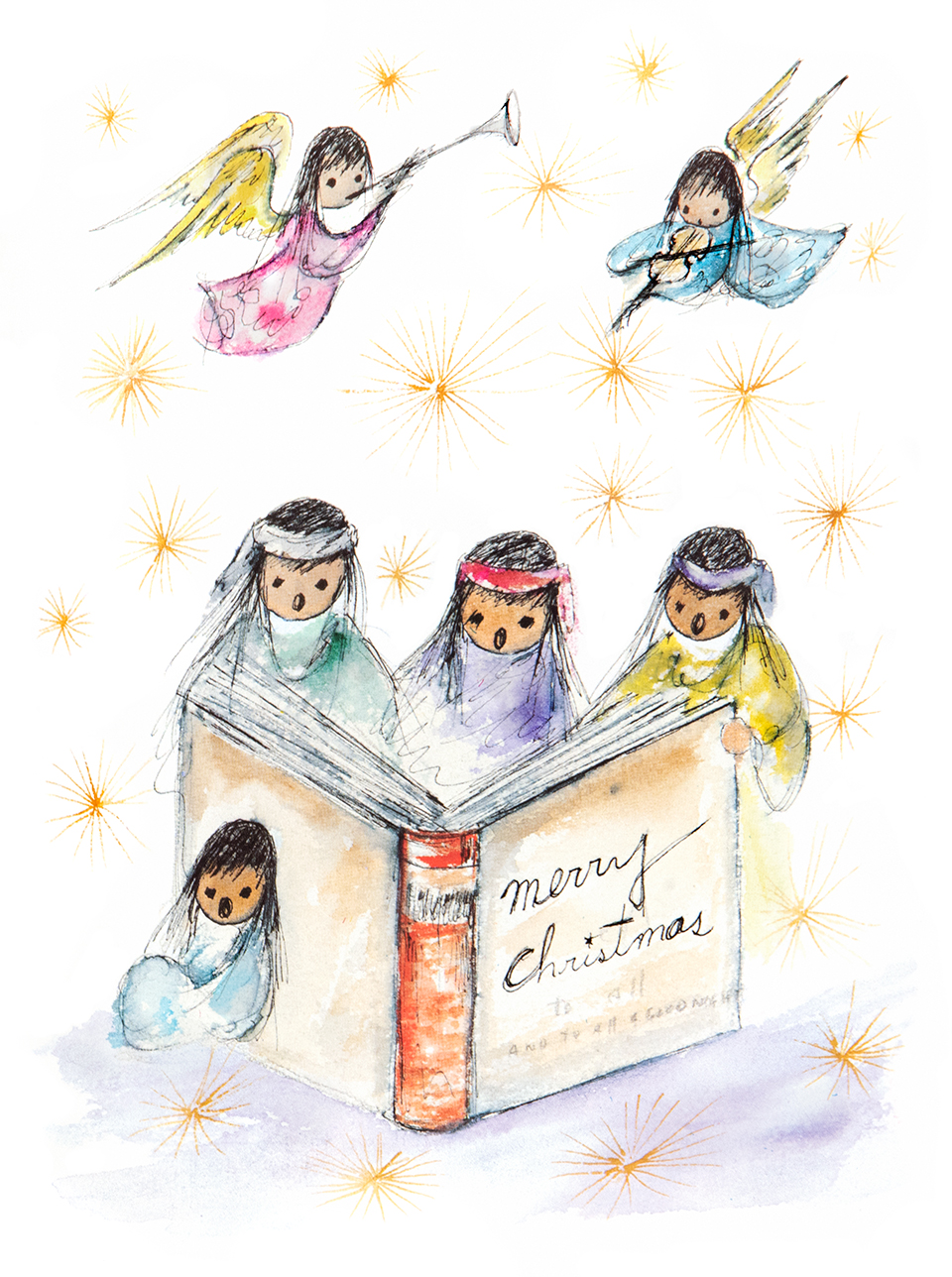

“Christmas to me is a season when the Arizona desert becomes a fantastic fantasy,” he wrote. “Angels about and around me — strange desert music everywhere. The nights are very silent and very long. The desert assumes a mood all its own. In the sky, the clouds become fanciful dream horses. The saguaro is being decorated with colorful streamers by the angels. The cholla is now a huge candelabra, memories of long ago. Desert memories of another world, another time.”

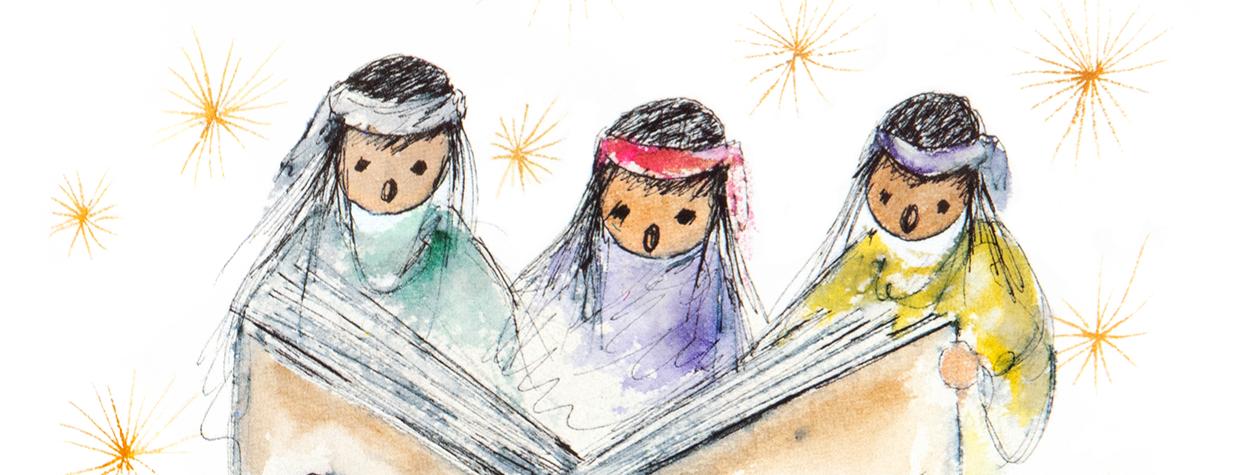

Nine of the paintings in that book are featured in this portfolio, along with his best-known holiday painting, Los Niños. That one didn’t make it into the book, but it had a life of its own.

It made its debut on page 20 in our November 1957 issue. It was one of several paintings in a piece written and illustrated by Mr. DeGrazia. At some point in the subsequent months, that issue found its way to the United Nations. Then, in September 1960, we got a letter. It was signed: “Mrs. Howard Edmunds, Art Director, UNICEF Greeting Card Fund, United Nations, New York.”

“As you know,” her letter begins, “the UNICEF Greeting Card Fund has been fortunate in receiving permission to reproduce as a greeting card this year a design which appeared in Arizona Highways. We are grateful to you for releasing the reproduction rights, and to the artist, Mr. Ettore (Ted) DeGrazia, for contributing his lovely design, Los Niños.

“The UNICEF Greeting Card Fund, which is now more than 10 years old, was begun as a way of telling people everywhere about the United Nations Children’s Fund. From a very modest beginning in 1950, with relatively few sales here at Headquarters, the program has grown to major proportions. During 1959, more than 14 million UNICEF cards were sold in 85 countries around the world. We are pleased not only with the breadth of the operation but with the very tangible results it produces for the Fund. All of the proceeds from the sale of our cards are used by the Children’s Fund in its worldwide programs to help developing countries improve the lives of their children.

“The card by Mr. DeGrazia is one of 11 different designs by six artists who, like him, have contributed their time and talents for the benefit of the Fund. Once again, thank you for all your help.”

In a response to her letter, Mr. Carlson wrote: “Viva DeGrazia! We have seen his UNICEF card and are using it for our personal cards this coming Christmas.”

By the time the holiday season was over in 1960, millions of Los Niños cards had been sold around the globe, making Mr. DeGrazia the most reproduced artist in the world. It’s what launched him into orbit, but it didn’t change the soft-spoken man, who talked with the hypnotic cadence of Bob Ross.

“When people ask why I paint the pictures I paint,” he said, “I do not answer, because the paintings are my life. They are my experience. They are what I have felt and what I have known. How can I explain this in a few words?”

Christmas Fantasies can be purchased at the DeGrazia Gallery in the Sun Museum

(6300 N. Swan Road, Tucson) or online at degrazia.org/shop.

To order UNICEF’s annual holiday card, please visit market.unicefusa.org.