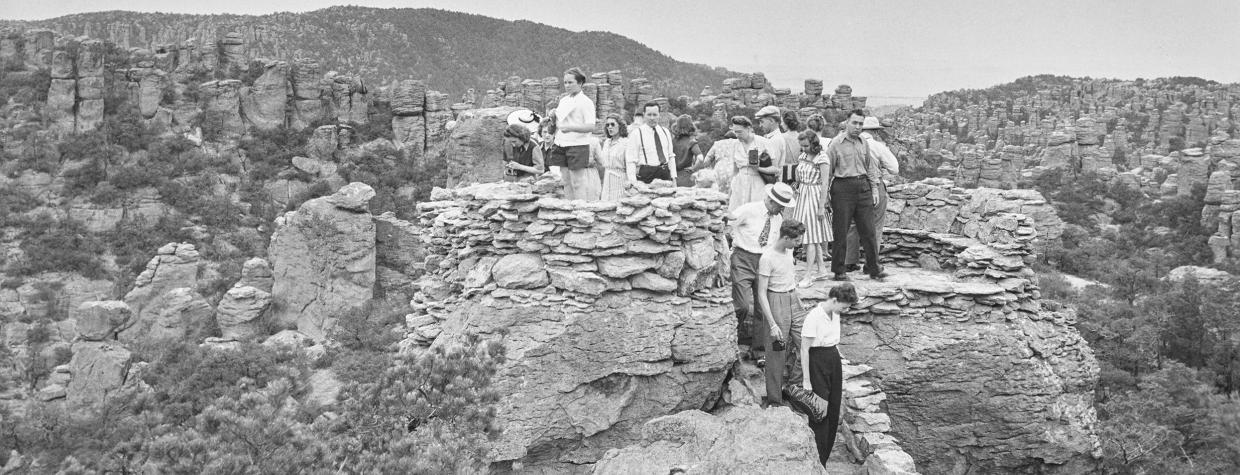

On Labor Day in 1934, some 7,000 visitors crowded onto Massai Point for the dedication of Chiricahua National Monument. While the Bisbee High School Bugle Corps played and dignitaries expounded, Civilian Conservation Corps enrollees sweated over 8,000 pounds of beef roasting in an 85-foot-long barbecue pit they’d blasted out of solid rock for the occasion.

National Park Service chief engineer Frank Kittredge was the first of several government representatives to speak. Since touring the monument five months earlier, Kittredge had become one of its biggest boosters. “In all the National Park and Monument areas, I know of nothing comparable,” he wrote to the editor of the Douglas Daily Dispatch. “The view from [Massai Point] can’t help becoming nationally famous and will rank along with some of [the] great spectacles of the country.”

The dedication was about a decade overdue. But there was a lot to celebrate. Not much had happened at the monument since President Calvin Coolidge had established it in 1924. But the road to Massai Point had just been completed, the CCC camp business leaders had lobbied for had been established, and hopes for the monument’s future looked as bright as the sun in the crystal-blue sky.

And now, as the monument celebrates its April 18 centennial with three days of special programming this month, legislation working its way through the U.S. House and Senate would, if passed, make Chiricahua National Monument Arizona’s fourth national park.

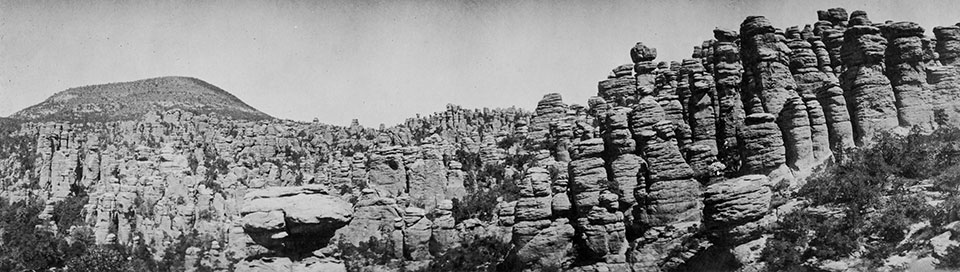

A century is a blink in geological time, and that’s especially true of the monument, which was created to protect the fantastical formations that resulted from volcanic eruptions 27 million years ago. Over time, natural forces fused the pumice and ash, then eroded it into a stone forest of pinnacles, columns and spires that look as though they were sculpted by a crazy, cosmic hand.

People who came to the area couldn’t help seeing these towering hoodoos in human terms, giving them names such as Old Maid and China Boy. In 1940, Joyce Rockwood Muench saw stone faces everywhere. “Through vistas in the trees, one is aware of crowds of rock people, watching from the canyon walls,” she wrote in Arizona Highways.

It’s as if a whole village were frozen in a moment in time, with villagers captured in earnest conversation (Punch and Judy) or in mid-kiss (the Kissing Rocks). And over them all, Cochise, whose band of Apaches raided from these mountains, lies in eternal slumber in the form of Cochise Head.

Perhaps it’s fitting that we see ourselves in these formations: The record of human occupation in the monument is rich and layered. Sometime before 1200, Indigenous people were climbing Sugarloaf Mountain to leave offerings. The land was also sacred to the Apaches, who came to listen to the voices of departed family members and use the future monument’s canyons for passage through the Chiricahua Mountains.

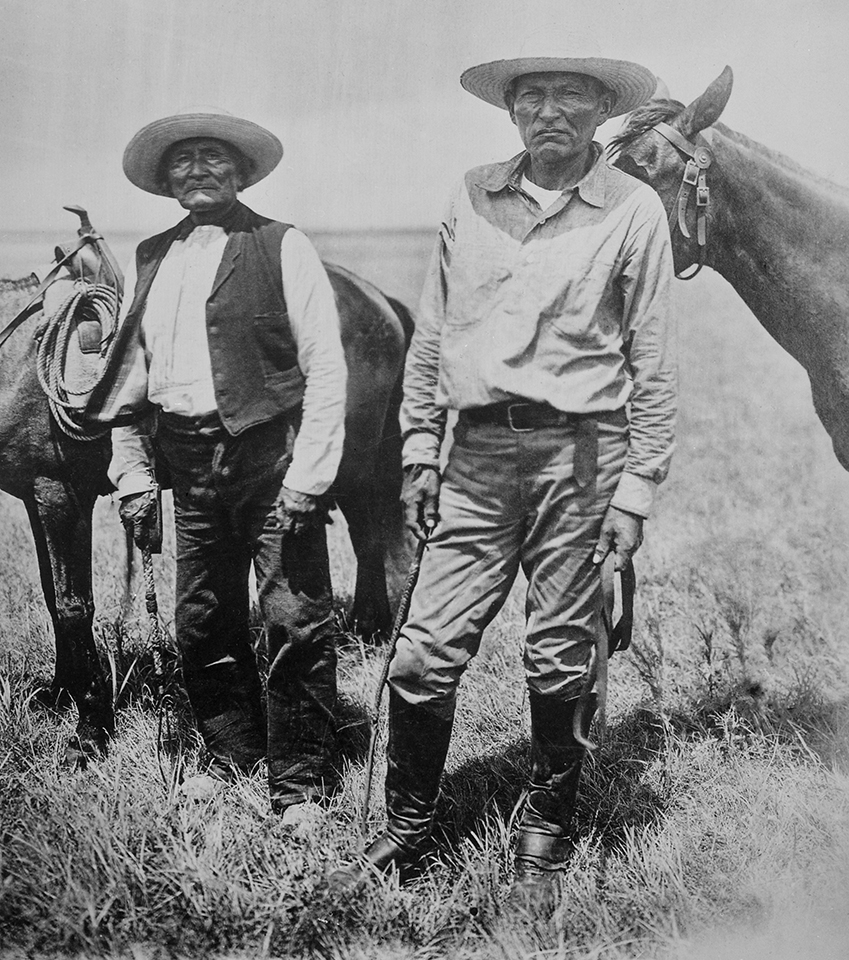

After the U.S. Army’s truce with Cochise in 1872, the future monument briefly became part of the Chiricahua Reservation. Home to about 1,000 Apaches at its peak, the reservation was abolished after four years and its residents removed to the San Carlos Reservation.

Cochise didn’t live long enough to see that, but Geronimo did. When the storied medicine man and his followers escaped from San Carlos in 1881, they hid out in the Chiricahuas, unsettling the earliest white settlers. According to family lore, Ja Hu Stafford, the first to file a homestead in the present-day monument, located his well inside his cabin for safety.

Stafford and his family must have breathed a little easier when the 10th Cavalry Regiment set up camp nearby. From 1885 until Geronimo’s capture the next year, the African-American regiment, dubbed the Buffalo Soldiers by the Plains Indians, occupied Bonita Canyon. The soldiers left a monument to President James Garfield, who supported giving Black people the right to vote but was assassinated in 1881, after less than a year in office. Decades later, the hand-carved stones from the deteriorating monument were repurposed as a house fireplace at the nearby homestead now known as Faraway Ranch.

Geronimo’s escape wouldn’t be Stafford’s last scare. After surrendering, a man named Massai escaped from a train carrying captive Apaches to Florida and may have turned up in Bonita Canyon in 1890. Swedish immigrant Neil Erickson, who had moved to Bonita Canyon two years earlier, captured the incident in his memoirs.

“This bright and early May morning Mr. Stafford was going to the fort with vegetables for officers and soldiers stationed there,” he wrote. Stafford was on his way to get the horses when he spied a moccasin; returning home to protect his wife and children, Stafford sent an employee to warn the Ericksons: “She came like a whirlwind, skirts a-flying, and said, ‘The Indians are coming down the canyon.’ ”

Stafford and Erickson followed the tracks up Bonita Canyon and over Whitetail Pass before turning back. The Apache had taken one of Stafford’s horses but otherwise left the settlers alone.

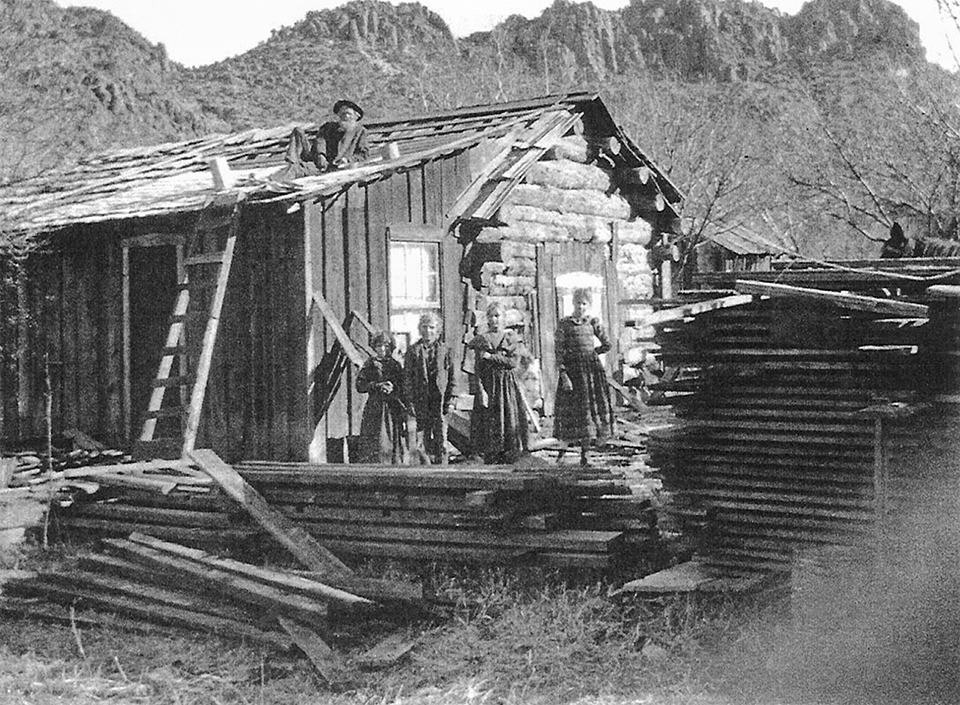

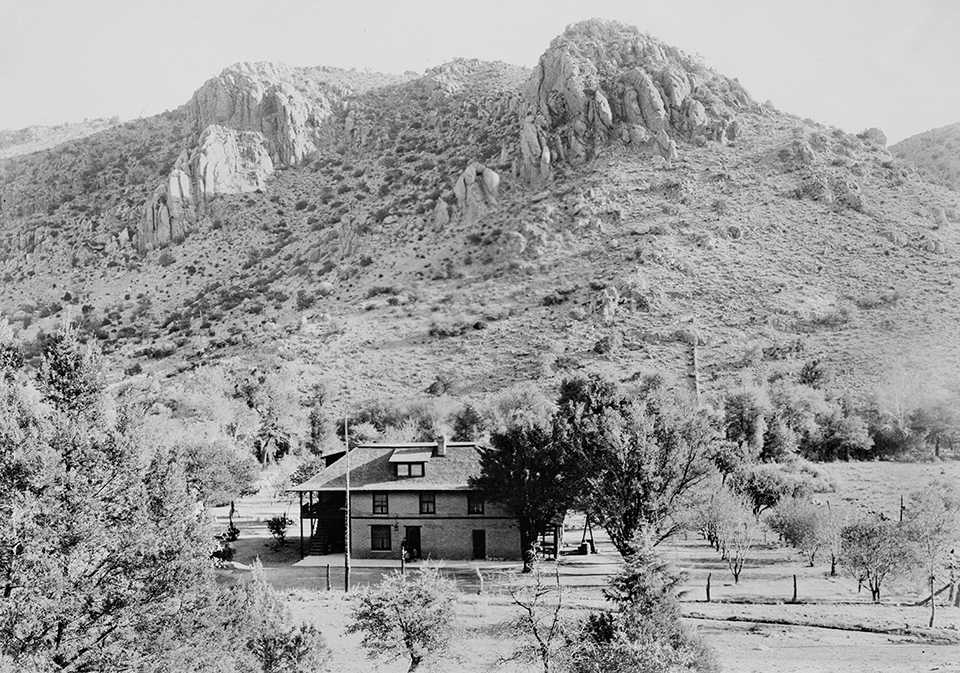

The Chiricahua Mountains were set aside as a forest reserve in 1902, and Erickson became one of its first rangers. His homestead in Bonita Canyon served as its headquarters, and he likely created some of the earliest horse trails into the future monument.

When a promotion in 1917 required Erickson and his wife, Emma, to move away, they left their two daughters, Lillian and Hildegard, in charge of the ranch because their son, Ben, had enlisted in the Army. Hildegard had been inviting friends for brief stays and by that time was considering opening the ranch to paying guests. “Much against Lillian’s wishes, I started the boarder business,” Hildegard wrote. “When our business was a proven success in the fall of 1917, Lillian gave up teaching and came home to assume managership.”

An aspiring writer with a genius for branding, Lillian named the business Faraway Ranch, because it was so “god-awful far away from everything.” After Ja Hu’s death, Lillian and Hildegard bought the Stafford homestead. Hildegard later got married and moved away, leaving Lillian to run the ranch alone. Lillian wrote to her father, “With you and Mama in Flagstaff, Hildegard married, and myself tied up with notes … there seemed nothing else to do but stick or die.”

Perhaps still not resigned to her destiny, Lillian went to Los Angeles to study writing in the summer of 1922. But she returned in the fall, and the next year, she married Ed Riggs, whose family had settled in the Sulphur Springs Valley in 1879.

The couple returned from their honeymoon with plans for “extensive improvements” to the guest ranch. They also began exploring the area Lillian called the “Wonderland of Rocks.” Recognizing its commercial potential, they promoted the area through chambers of commerce and the county fair.

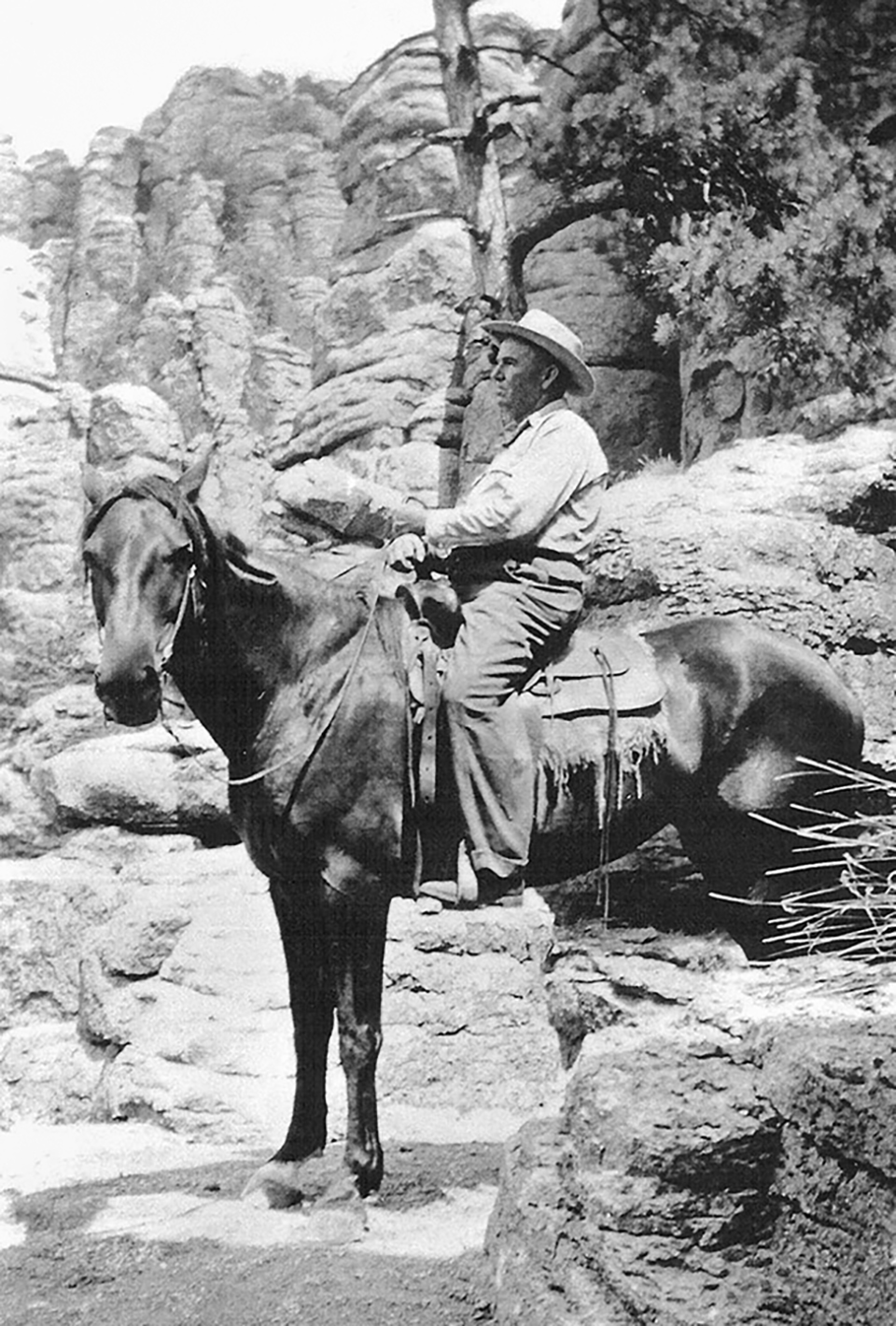

With help from an American Legion committee in Douglas, they also began campaigning to make the Wonderland of Rocks a national monument. In August 1923, Ed led Governor George W.P. Hunt and a party of 60 reporters, photographers and business leaders through the area called the Heart of Rocks, following a trail Ed and Lillian had built for the visit. Hunt threw his support behind the campaign, and the efforts were rewarded with Coolidge’s proclamation the next year.

With no funds to develop recreational facilities, the designation didn’t change much beyond the name. For nearly a decade, the monument remained under the administration of the U.S. Forest Service, which used private contracts to build the first road into Bonita Canyon and also added a small, primitive campground.

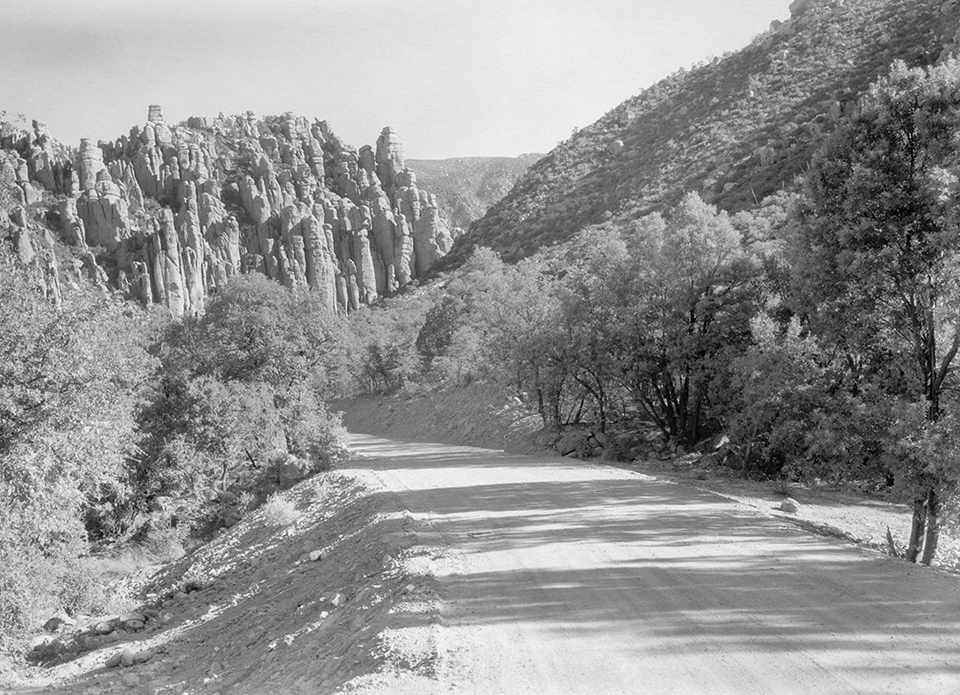

In 1930, as the Great Depression devastated Southern Arizona’s economy, local business leaders met with Coronado National Forest supervisor Fred Winn to lobby for a better road that would reach farther into the monument. Under Forest Service supervision, state and federal road crews broke ground on the new Bonita Canyon Road in 1931.

Built as the monument’s central artery, the road was designed to create a series of visual experiences, highlighting formations such as the Organ Pipe Formation and the Sea Captain, before terminating with a sweeping view at Massai Point. “It becomes a road with a genuine climax,” the Tucson Citizen declared, “for when it has been finished it will bring the traveler suddenly upon the great area of this rocky wonderland, the likes of which there is no other on this continent.”

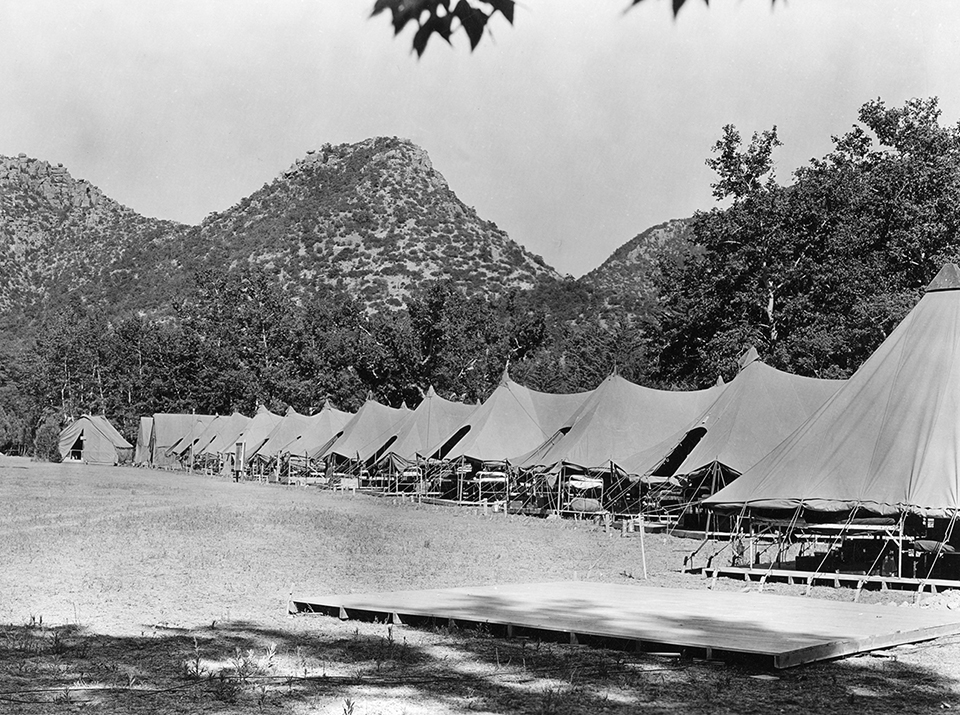

As the road neared completion in 1934, business leaders began planning an ambitious dedication, both to generate publicity for the monument and to justify a CCC camp to develop it. The Park Service’s Southwest monuments superintendent, Frank Pinkley, visited in April and soon afterward applied for the camp. The next month, a CCC unit from Tucson Mountain Park moved to Bonita Canyon, setting up on the Riggses’ Silver Spur Meadow, and Ed signed on as trail crew foreman.

During the next six years, enrollees improved the scenic drive and constructed all visitor and staff facilities, including hiking trails, the monument’s headquarters, a fire lookout and three ranger residences. They also enlarged the campground. Among the Southwest’s national monuments, only Bandelier, in New Mexico, saw as much development by a single group in such a short time. But the first order of business was to prepare for the dedication set for Labor Day.

The dedication committee envisioned nothing less than the “biggest outdoor gathering ever held in Southern Arizona” and publicized it in newspapers as far away as Los Angeles and El Paso. Members expected as many as 10,000 visitors would experience the wonder of Bonita Canyon Road before arriving at Massai Point. There, speakers would hold forth in a natural amphitheater from a dais constructed of local rock, a view of the Wonderland of Rocks and the Sulphur Springs Valley spreading out below.

Everyone but the Park Service was excited. The idea of tearing up 4 or 5 acres to accommodate parking for a one-day event gave Pinkley “the jitters.” It was too high a price, he said, lobbying to instead hold the dedication ceremony at Faraway Ranch.

“How much change of appearance ... can [we] impose without laying ourselves open to the charge of vandalism?” he wondered. If asked, the Park Service would have to explain, without irony, that it was all done to dedicate a monument created “to hold it for all time in its original beauty for the enjoyment of untold generations.”

The committee was undeterred. Initially expected to require 10 men laboring for one month to complete the work on Massai Point, preparations instead required all of the camp’s resources “in men, machinery and equipment.” And the appearance of Speaker’s Rock, created in haste by men who had not yet honed their skills, so distressed Park Service engineer Walter Attwell that he offered to tear it down and rebuild it. “I would say it was a disgrace,” he said.

Still, the event was declared a rousing success, despite some disappointment with the attendance and the absence of a key speaker from the American Federation of Labor. The weather was mild, an Army band performed, and Kittredge shared the rostrum with Winn and U.S. Senator Harry Ashurst of Arizona.

Today, only Speaker’s Rock remains to mark the event. Enrollees built an orientation station on one of the temporary parking areas. When Camp NM-2-A closed in 1940, the federal government turned the buildings over to Ed and Lillian Riggs as compensation for the use of their land. The Riggses operated Camp Faraway at the location for a few years before selling the meadow and buildings to William Spragge, who further developed them into the Silver Spur Guest Ranch.

Spur Guest Ranch. | Spragge Family Collection

Ed died in 1950, and after operating Faraway Ranch sporadically, Lillian shuttered it for good in 1970. The ranch properties were sold to the federal government to be included in the monument. The camp buildings were demolished, but the alligator junipers that enrollees planted and an enclosure they built for their pet bear cub remain, along with two stone fireplaces Spragge built onto the camp’s former mess hall. In 1976, most of the monument was designated a federal wilderness area.

Despite Kittredge’s prediction of national fame, Chiricahua has remained something of a hidden treasure, which the confusing designation might partly explain: Visitors often show up looking for a plaque or statue, not realizing the entire area is the monument. National park status could end that misconception and raise the site’s profile. In the meantime, 20 Erickson family descendants plan to attend this year’s celebration, which this time will be held at Faraway Ranch. No doubt, Frank Pinkley would approve.

To learn more about Chiricahua National Monument, call 520-824-3560 or visit nps.gov/chir.