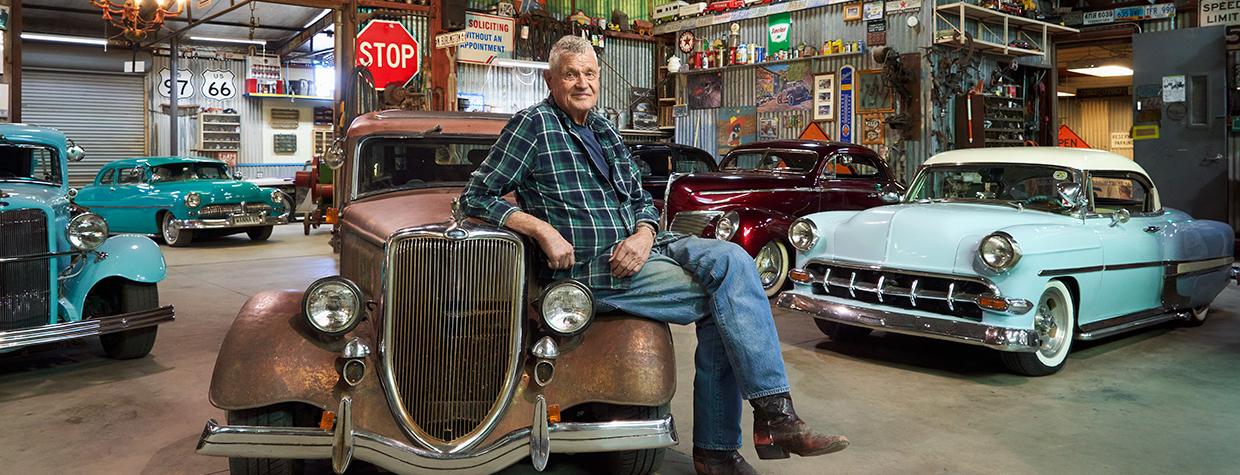

I find Ernie Adams, signature green Fire King coffee mug in hand, at the Dwarf Car Museum when I arrive. Adams recently turned 82 but looks much younger, his 6-foot frame nearly as lean as in pictures taken decades earlier. You’ll find him at the museum almost every afternoon, answering questions from visitors who come to marvel at the detail and craftsmanship of his miniature classic cars. Or you might find him hard at work on the replica 1941 Chevrolet that might be his last.

Surrounded by desert in a sparsely populated part of Maricopa, the Dwarf Car Museum is not a place that visitors happen upon. Yet enthusiasts from 65 countries have made their way there — as many as 100 a day visit in the winter months — thanks to stories in magazines around the world and segments on television shows such as Jay Leno’s Garage.

Most of the museum’s 15 dwarf cars meticulously duplicate vintage autos, down to the flamethrowers on the replica ’49 Mercury and the Mercury emblem (taken from a refrigerator) that adorns its steering wheel. The only noticeable difference is that the tops of these cars reach about as high as Adams’ waist.

“That was the first street-legal [dwarf],” Adams says, gesturing to a replica ’39 Chevy. The glossy black car sports moon hubcaps, fender skirts and Venetian blinds in the rear window. Adams has driven it nearly 51,000 miles, beginning with a trip to Des Moines, Iowa.

But his favorite ride is an unpainted dwarf ’34 Ford sedan inspired by the memory of a car that family friends once owned. “I was just about as tall as the front tire, maybe the front fender,” Adams recalls. “I would stand in the driveway and watch that old wheel roll into our driveway, and it stuck in my mind.”

Opening the driver’s-side door, Adams reaches in and fires up the engine. “It’s got dual horns,” he says, demonstrating. “It’s got a radio, heater, defrosters, ashtrays, cigarette lighter, glove box. The windows roll up and down. It’s just like the real car. It’s even got 24 louvers in the hood and 32 spokes in the wheels.”

Growing up in the small town of Harvard, Nebraska, Adams thought of the city dump as a free department store. He’d salvage old appliance motors, get them running and attach them to anything with wheels: bicycles, tricycles, even an old wicker wheelchair. Eventually, he graduated to wooden cars and one made from bed frames and bicycle wheels.

Looking out the window one day, Adams noticed a white refrigerator lying in the weeds and thought its curves were about right for a car body. In 1965, using an arc welder and a hacksaw fashioned from a chair frame, he cut up refrigerators and assembled them into his first dwarf, styled like an open touring car.

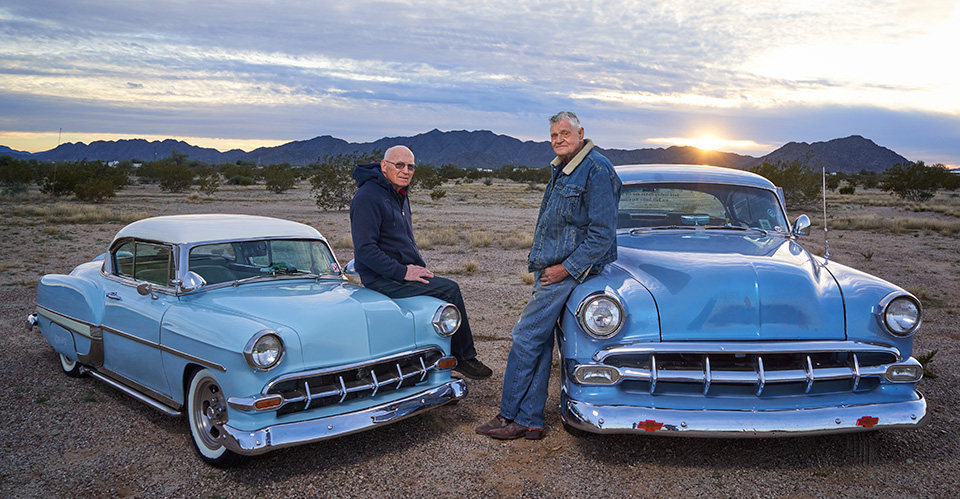

Adams was living in Arizona in the late 1970s when he got the idea to build dwarf race cars while watching motorcycle sidecar races with a buddy. Agreeing they would each try their hand at building one, the two men gathered sheet metal and tubing from Adams’ backyard and set to work.

In a documentary that Adams’ son, Kevin, produced and that runs on a loop at the museum, Adams recalls that the early racers were “quite crude.” It took about a month to build his first. That car was bought and sold four times before Adams got it back, trading it for a new dwarf race car with a bigger motor. It’s now displayed at the museum.

Adams and his friends raced their dwarves in the desert until a friend organized races with a paid purse. The first took place in 1983 at the Yavapai County Fairgrounds in Prescott. After building dwarf race cars for about 10 years, Adams quit to work on more refined cars. Starting with a Toyota motor and drivetrain, he began fashioning car bodies from flat sheet metal using homemade bead rollers and dies. Except for the upholstery, he figured out how to make everything from bumper to grill, down to door handles and steering wheels.

With names such as Precious Memory, most of the dwarves were inspired by Adams’ past, and the museum is as much about his life as it is about his cars. Kevin designs the T-shirts and mugs for sale in the gift shop. Kevin’s wife, Ginger, runs the shop and directs visitors to displays of vintage toys and trophies. She points out the wood-burning stove salvaged from Adams’ childhood home and the window from which he saw the refrigerator that inspired that first dwarf. The family even relocated that home’s outhouse.

“We had to put up signs saying, ‘Please do not use,’ ” Ginger says with a laugh. “[Visitors] got confused and thought it was where they were supposed to go.”