Desert View Watchtower looks as if it’s been standing on the edge of the Grand Canyon for 1,000 years. Rising 70 feet, the circular stone structure appears to emerge straight out of the Earth, as naturally as the junipers growing nearby along the rim.

The watchtower is perfectly imperfect, the product of architect Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter’s obsessive attention to detail and her use of uncut stones found nearby, each placed just so to create the shadows and textures she was seeking. “Time, the lost principle in much modern construction, was taken to select each rock for the outer walls,” Colter would write in her Manual for Drivers and Guides, a detailed document she created to answer questions Grand Canyon tour guides might have about the tower.

Colter bristled at the notion that the tower was a reproduction, replica or copy of any single structure. Nor did she want visitors to think it was a restoration of an existing Ancestral Puebloan building that had stood on the site. Instead, Colter based the tower’s design on features she noted at an assortment of ancient sites she visited and studied around the Southwest, including Mesa Verde National Park, in Colorado, and the circular towers at Hovenweep National Monument, along the Utah-Colorado border. She preferred to call the watchtower a “re-creation” and wrote, “It is not an exact reproduction of any known ruin; but, rather, is based on fine examples of the prehistoric workman, and is built in the Indian spirit.”

Colter’s 1932 “re-creation” is now being reimagined as the centerpiece for the Desert View Inter-Tribal Cultural Heritage Site, a project between the National Park Service, Grand Canyon Conservancy, the Bureau of Indian Affairs and a working group consisting of members of Arizona’s 11 American Indian tribes with cultural and spiritual connections to the Canyon.

Often described as the most American of places, Grand Canyon National Park has not always been a welcoming place for American Indians. The human presence in the Canyon dates back at least 12,000 years, but over the past 150 years, the region’s tribes have frequently been cut off from their ancestral lands and excluded from park decision-making. At the rededication of the tower in 2016, then-Superintendent Dave Uberuaga formally apologized and asked forgiveness on behalf of the Park Service and his 23 predecessors. He declared the Desert View area “a place for all tribes to call their own.”

The project is the first of its kind in the national park system. “This is a generational shift,” says Jan Balsom, senior adviser for stewardship and tribal programs at the Canyon. “It will take generations to transform Desert View into the place we want it to be: where tribal members staff the site, tell the history and demonstrate the artwork. It’s a long-term investment in change — to change the dynamic so the parks aren’t in charge and we’re working in collaboration with tribal members to make this site work.”

The heritage site aims to turn the watchtower and the Desert View area into an Indian community gathering place where park visitors can learn about and experience tribal cultures directly from craftspeople, dancers and storytellers. The guiding concept is “First Voice”: the idea that Indigenous people should relate their own histories, contemporary experiences and aspirations for the future, rather than having these stories filtered through intermediaries from outside their communities.

Talk to park rangers, and they’ll tell you many visitors wonder where the Canyon’s tribes have gone. The fact, of course, is that they never left. These Indigenous people still live here, as they have for countless generations. As Havasupai medicine woman Dianna Uqualla said in a video produced by Grand Canyon Conservancy: “Our history, of the Havasupai people, this is their aboriginal homeland. This is where our first beginning, our people were. A lot of this land base right here has our ancestors’ footsteps, our ancestors being here. Living off the land. This whole Canyon as a whole is a very sacred, sacred place in our eyes. And we still, the Havasupai, exist. And we still watch over it as much as we can.”

For travelers arriving from the east along State Route 64, Desert View Watchtower is a must-stop — their first chance to peer into the abyss and take in a panorama that includes a long stretch of the Colorado River, from Unkar Delta to the confluence with the Little Colorado River and into Marble Canyon, before extending more than 100 miles out to the Painted Desert.

Just as the project reimagines the watchtower, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places with three other Colter masterpieces (Hopi House, Lookout Studio and Hermits Rest), it may also help visitors rethink the Grand Canyon itself. Most visitors regard the Canyon as a geological wonder to hike and explore. Or they come to simply stand along the rim and take in views of the mile-deep labyrinth of eroded stone that extends for 277 miles across Arizona. In fairness, it’s easy to be overwhelmed by the overwhelming, and the scale and majesty of the Canyon means tourists typically end up thinking of it solely as a natural landscape, rather than a cultural one. But tucked into alcoves within the Canyon are the stone walls of dwellings and granaries built centuries ago. And right off the highway, about 3 miles from Desert View, is 800-year-old Tusayan Ruin, the most accessible of the 4,000 archaeological sites in the park.

When you look out from the watchtower, you’re seeing Navajo, Hopi and other tribal lands, as well as the San Francisco Peaks, which are sacred to multiple tribes. Indian lands border the national park for hundreds of miles. The 11 Canyon tribes themselves are hardly monolithic: Their cultures are rich and varied, with distinct languages, traditions, histories and beliefs.

The Zuni people regard the Canyon as a place of origin, and according to Hopi tradition, the Canyon is where their people emerged into our world. Havasupai territory reaches from the rim all the way down to the river. Some Havasupais live deep within the Canyon, growing corn, squash and beans not far from the turquoise waterfalls and pools that gave the tribe its name, which translates to “People of the Blue-Green Waters.” But for nearly a century, until 185,000 acres of the plateau were returned to the tribe in 1975, the Havasupais were displaced from the rim and restricted to just 518 acres along the Canyon bottom.

The park borders the Navajo Nation to the east, and in many ways, that administrative boundary contributes to a sense that the park is somehow separate from the surrounding lands. There have also been tensions about regulations that restricted traditional practices, from piñon pine nut gathering to prohibitions on artisans setting up stands or tables to sell works inside the park.

Mae Franklin previously worked as Navajo tribal liaison to the Kaibab National Forest and the national park, and she now represents the tribe on the park’s Inter-Tribal Advisory Council. She believes the heritage site is part of a growing effort to recognize the tribes’ legitimate stake at the Canyon.

“This is our homeland; it’s part of what we have known all of these years,” Franklin says. “The Park Service had to deal with these issues and needed to change, because they knew we weren’t going to go away. … They took the concessionaire out and put Desert View back under the park, so that the park could work with the tribes and give the voice back to the tribes. That’s what this is. Providing a place where we can tell our stories, where we can have a voice. We’re hoping it’s not the only place in the park. But it is a beginning, and our community is starting to understand that the park is listening and responding in a responsible way.”

As project planning began, it was essential to hear Indigenous voices from the earliest stages. But bringing the tribes together with park representatives wasn’t as simple as putting everyone in a conference room and checking items off an agenda, says Sammye Meadows, a writer, historian and expert in Indigenous tourism who took part in the meetings as a representative of the American Indian Alaska Native Tourism Association (AIANTA). Trust issues, both with the Park Service and in some cases between the tribes, couldn’t be ignored.

The 11 Canyon tribes themselves are hardly monolithic: Their cultures are rich and varied, with distinct languages, traditions, histories and beliefs.

“The first thing to do was to gingerly feel out how much each group could trust the other one, as well as the Park Service, because of the way the park was established,” Meadows says. “There was a lot to overcome, even though there’s been cooperation over many, many years protecting cultural sites in the Canyon and water flows. But First Voice interpretation and [having] a place of our own was a big step beyond that. During some of those early meetings, there was a lot of griping about the Park Service: ‘Yeah, yeah, you say this, but you never come through.’ There was plenty of that. And every time new park leadership came along, everyone would hold their breath. But people are more trusting now.”

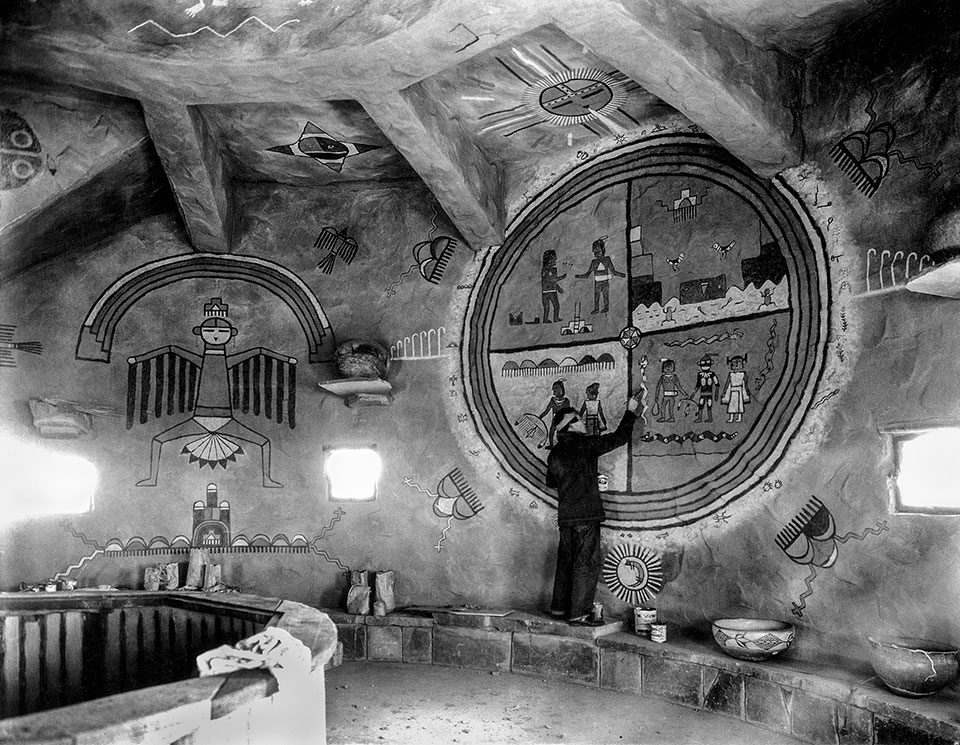

Colter said she built the tower with an Indian spirit, and the question was how to turn Desert View back into a place Indians would feel belonged to them, instead of serving as just another overlook. Historically, the area had been an Indigenous gathering place, and Colter wrote that Hopi artist Fred Kabotie, who painted the tower’s magnificent interior murals, told her the point was a Hopi landmark that identified “a boundary to their ancestral domain.”

As the group began to consider physical improvements to the site, differing cultural perspectives quickly became evident, says Theresa McMullan, executive director of Grand Canyon Conservancy. “We were walking the grounds and talking about what type of fencing or barriers you would put in along the paths,” she recalls. “Some of the tribal members were kind of shaking their heads and said, ‘We don’t have barriers, we don’t have borders.’ To think about that — once you start thinking about things from different perspectives — it really opens your mind, which is so important right now.”

Meadows says tribal members also wanted a bread oven, because the aroma of bread baking outdoors would be a sensory reminder of their own communities. And they resisted changes that may have been appropriate for a park pullout, but less so for a tribal area. “One part of the plans and drawings showed a pathway that goes all the way around the rim, on beyond the watchtower,” she says. “At first, they were talking about maybe putting in benches and interpretive signs, and the tribes said, ‘Well, how about if you don’t put in any of that, just make that a trail? We can use that area if we want to do a sunrise ceremony or take our kids out there for some teaching. That could be for us.’ I think that’s what they’re going to do in that area, instead of designing it as the endpoint of visitation.”

AIANTA secured a $500,000 grant for cultural programs and restoration work from ArtPlace America, a public-private partnership that advocates for incorporating the arts into community planning and economic development. Before the tower closed and events were suspended because of the COVID-19 pandemic, tribal members conducted demonstrations of pottery making, silversmithing and weaving. There were also dances and storytelling that gave participants the chance to take control of their cultural narratives. As Meadows says, “If you don’t tell your own story, someone else will.”

That can make a huge difference, as Franklin discovered on Colorado River trips with both Indigenous and non-Indigenous guides. “It’s like night and day,” she says. “With some river guides, the trips are kind of a party thing. With the tribes, they say prayers. That totally changed the experience.”

For decades, any notion that the watchtower was some ancient structure quickly dissipated as you entered not a sacred kiva, but a gift shop selling all manner of Canyon souvenirs and bric-a-brac. Meadows says the removal of the store and establishment of the heritage area is changing how tribal members perceive the watchtower itself. “I just remember in the beginning, when I first got involved, hearing some of those guys joking, ‘Well, if they had asked us when they first put the thing up, we’d tell ’em [to] just push it over the edge. We could still come in some night and push it over the edge,’ ” she says. “They used to make jokes like that. And then, more recently, because of the artist demonstration projects and clearing out the concession, guys say, ‘We’re going to live with this thing. It’s finally doing us some good.’ ”

With the retail clutter banished, Colter’s kiva — what she called the View Room, thanks to its large windows — again opens unobstructed to the Canyon. It’s also much easier to appreciate the detailed craftwork, including the stone pilasters and, most notably, the elaborate cribbed-log ceiling, constructed using a traditional technique Colter had observed in the pueblo at Aztec Ruins National Monument in New Mexico. Cut 43 years earlier, the logs used in the ceiling were salvaged from the demolished Grandview Hotel.

For all of her respect for Indigenous cultures, Colter engaged in practices that today would not only be considered culturally insensitive, but also violate current federal law protecting antiquities. In addition to the stone from nearby canyons, she incorporated sections of ancient petroglyphs removed from sites near Ash Fork and Joseph City. If the stones in the tower walls weren’t just right, Colter ordered the crew to remove them and start over. Some of the men who worked on the tower dubbed her “Old Lady Colter,” although, in fairness, she did face the challenge of directing an all-male crew.

From the kiva, you once had to pay a quarter to go through the turnstile and enter the tower itself before slowly ascending the curving walkways to view Kabotie’s murals. Those murals have been painstakingly restored by hand to bring back the vividness of the original gold, pink, brown and turquoise oil-based pigments Kabotie used. Time and weathering, from rain and snowmelt that seeped through the stone walls and created salt deposits, had taken a toll.

Fred’s grandson Ed Kabotie, a musician and artist, worked on the mural restoration team. As he said in 2016: “This was a real thrill to me, to be able to come out here and work on a historic building of my grandfather. It’s very powerful for me. This watchtower, to me, represents a very different time and a very different relationship. It represents a time when the Canyon had a very interactive relationship with tribes. So many different cultures come to this place every day. The conservation project, in some ways, is like a revitalization of the relationship between the Canyon and the tribes.”

Colter said she built the tower with an Indian spirit, and the question was how to turn Desert View back into a place Indians would feel belonged to them, instead of serving as just another overlook.

If Colter aimed to infuse the tower with the Indian spirit, it is Kabotie’s murals, as well as pictographs painted on the ceiling by artist Fred Geary and based on the rock art from a cave in New Mexico, that truly give the building its soul. Colter described Kabotie as “one of the three greatest modern Indian artists” before later writing, “Every line he draws is as sure as truth itself.” But — proving that cross-cultural communication problems are not an exclusively contemporary phenomenon at the Canyon — she and Kabotie sometimes clashed. A stubborn perfectionist, Colter was committed to her vision, and as Kabotie diplomatically put it, “Miss Colter was a very talented decorator with strong opinions, and quite elderly. I admired her work, and we got along well … most of the time.”

By the standards of the Canyon’s tribes, the murals, even at nearly 90 years old, are recent works. Despite their age, Kabotie’s depictions of the Snake Dance and Hopi legends hint at something deeper and far more ancient at the Canyon. “That’s a lot of what Fred Kabotie was trying to show inside the watchtower,” Meadows says. “It’s about the land and the story of Hopi. When people start looking at the Canyon as someone’s home for 12,000 years, everything changes in their brain cells. It changes their thinking.”

Now, thanks to the Desert View Inter-Tribal Cultural Heritage Site, it’s up to the rest of us to open our minds and start listening to the true voices of the Grand Canyon.