When you’re driving to Temple Bar, there are two things you have to remember: Stay on the paved road, and keep going. Those directions are straightforward enough that you wouldn’t think people would have trouble. But people have trouble. “They come in,” says Lisa Duncan, who lives and works at the site, “and they’re like, ‘You were right! I was so tempted to leave the road!’ ”

Temple Bar, on the Arizona side of Lake Mead, is a relative rarity: The well-maintained road means just about anyone can get to it, but the distance — about 80 road miles from Kingman or Las Vegas — means few know it exists and even fewer make the trek. And that combination isn’t the only uncommon thing about this place. Its marina, restaurant, motel and campground make it the only developed area on Arizona’s portion of the reservoir. For three-quarters of a century, it’s provided services to boaters, campers, anglers and anyone else in search of sun, solitude and starry night skies.

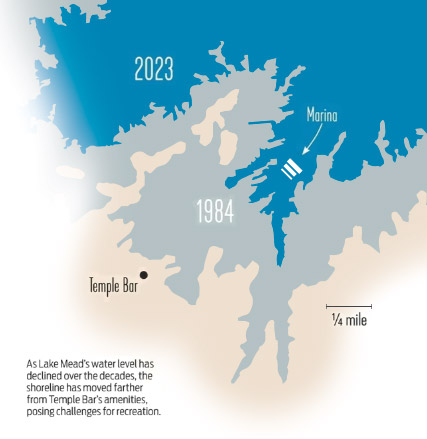

But today, the future of this place is as murky as the overtaxed Colorado River, which sustains Lake Mead as best it can. Declining water levels have moved the lakeshore ever farther away, leading the National Park Service to recently stop maintaining Temple Bar’s boat ramp. Advocates worry that further shrinking of the reservoir could mean the loss of other visitor services, which would leave Arizonans without a place to recreate on the lake — and the state without a way to generate revenue from it.

For now, though, the people who stay on the paved road keep finding ways to occupy themselves. Or not — and at Temple Bar, that’s kind of the idea. “Some people come out here and ask, ‘What’s there to do?’ ” says Curt Elmore, whose ties to this place date back nearly 60 years. “We’ll hear things like ‘I can’t get Wi-Fi’ or ‘My cellphone doesn’t work.’ Yeah! Isn’t that awesome?”

There aren’t many people at Temple Bar who can point out the house where they grew up. In fact, Elmore — whose father was a Park Service ranger at Lake Mead from 1968 to 1972, with a few stints in Washington, D.C., during that time — might be the only one. “You can see this eucalyptus tree from Meadview,” he says during a tour of his old neighborhood. “And we had a salt cedar, over by these oleanders, where I built a treehouse.”

Temple Bar’s human history dates back much further. In pre-settlement times, peoples including the Basketmakers and the Southern Paiutes inhabited the area, and in the 1890s, a French company operated a placer mine nearby. But after Boulder Dam (now Hoover Dam) manifested a shoreline in this patch of desert in the late 1930s, recreation facilities were the next logical step.

The first guest cabins appeared in 1947, along with a dock, a floating store and an airstrip. Later concessionaires added a restaurant, a more permanent store and the site’s trailer village, along with more cabins and motel rooms. The building boom included Pickle City, a neighborhood of 37 half-acre leases on which vacationers could build their own homes. (There are a few theories about the nickname, but the prevailing one is that with nothing to do, early residents got drunk most of the time.) These days, the Park Service is slowly reclaiming the leases, but existing leaseholders can stay until they go to the giant pickle in the sky; among the houses still in use is one belonging to actor Lee Majors, the Six Million Dollar Man himself.

By the late 1960s, Temple Bar looked much as it does today, with amenities including a wood-shingled motel, a gas station, a restaurant and a relatively lush campground. The ranger station, which boasts a striking midcentury modern design, dates to the early ’60s. And while additional expansion would have featured condos, art galleries and even a golf course, those plans evaporated due to low visitor numbers.

Still, Temple Bar has seen its share of publicity — and notoriety. It’s been mentioned in the pages of Arizona Highways since the early 1940s, and it later was featured in the 1950s radio drama Yours Truly, Johnny Dollar and the 2007 Sean Penn film Into the Wild. But Elmore also recalls the place’s “party hearty” vibe, particularly an evening when his dad returned home with discarded syringes he’d collected from a nearby beach secured in his hatband. “It was the ’70s,” Elmore says.

The vibe these days — at least during a late-September visit, just past the summer peak — is a bit more sedate. And that suits Elmore and his wife, Cecilia, just fine. After retiring from their civil engineering careers, the two moved to Arizona from Missouri. Since 2018, they’ve been volunteers for Lake Mead National Recreation Area, and when they’re not out on a patrol boat or interacting with visitors, they split their time between a Temple Bar trailer and their permanent residence in Lake Havasu City.

“I thought it was gorgeous,” Cecilia says of her first time seeing Lake Mead, on one of the couple’s summer water-skiing trips from the Midwest. “You can ski for miles and miles and not see anybody.” And the combination of an east-west river course and prevailing southerly winds makes Temple Bar an ideal spot to head out in their boat for a morning ski. They’ve spotted burros and bighorn sheep in Lake Mead’s numerous coves, and they’ve hiked to remote locations such as Salt Spring, where water collection boxes from the mining days can still be found.

But the receding shoreline — a result of drought and increased water use by Southwestern states — has made recreation a challenge. As recently as the 1990s, Lake Mead came right up to Temple Bar’s restaurant; now, it’s about three-quarters of a mile away. For decades, the Park Service extended the site’s boat launch ramp to accommodate the changing reservoir, but in July 2021, the ramp was abandoned, leaving boaters high and dry.

The site’s current concessionaire, Guest Services International, has since deployed a Mobi-Mat, a type of portable launch ramp, adjacent to the abandoned one. So far, it’s working fine. But the 2021 ramp closure sparked worries that ending the site’s concessionaire contract could be under consideration.

The effects of such a move would be far-reaching. Arizonans looking to enjoy Lake Mead would have to travel to Nevada to reach lakeside areas with visitor services. People exploring via boat would be without a vital refueling station, limiting the places they could reach on the east side of the lake. And Arizona would lose its only way of generating tax revenue from recreation at the country’s largest reservoir. (Two other developed areas in Arizona, Willow Beach and Katherine Landing, are part of the recreation area but are downstream from the lake.)

Lake Mead public affairs officer John Haynes says the Park Service’s short-term vision for Temple Bar is “to continue to provide all the services we can, unless we get to the point where the lake is so low that it’s not effective to stay open anymore.” He adds: “The goal is to keep it open. Right now, we’re trying to find creative ways to provide services out there.”

Indeed, providing services at a place like Temple Bar seems central to the purpose of Lake Mead National Recreation Area. As spelled out in the 1964 legislation that created it, the recreation area — the nation’s first — must be operated “in a manner that will preserve, develop and enhance, so far as practicable, the recreation potential.”

And if the Arizona side of Lake Mead were out of reach for most visitors, a lot of recreation potential would be wasted.

On a pontoon boat cruise up Virgin Canyon, southeast of Temple Bar, one thing is clear: Despite the dire headlines, there’s a lot of water in Lake Mead. In fact, while the receding shoreline has created a few hazards for boats, much of the reservoir remains more than 200 feet deep.

On the Nevada side, across from Temple Bar, Elmore points out the Temple, the steep-walled monolith for which the site is named. Along the way are other landmarks, such as Gilligan’s Island, which is no longer an island; Gregg’s Hideout, a cove named for an early river ferry operator; and Striper Bay, spelled on some maps with an extra “P” — which is either a typo or a nod to the area’s rowdy days. And atop a lakeside cliff, Elmore spots an inoperative “wind talker,” a device that dates to his childhood. “If that was blinking, you knew it was windy,” he recalls.

Back on land, Duncan, who manages the site’s operations for Guest Services International, leads a tour of the Temple Bar area, including Heron Point, an overlook with a dramatic view of the reservoir; the campground, which is shaded by tall palm, eucalyptus and olive trees; and the nearly 100 trailers, some of which date to the 1950s. By Park Service rules, tenants can spend no more than 180 days per year in their trailers. (Most of them abide.)

The site’s marina is the smallest such facility on the lake. That, plus its location near the river channel, makes it the marina most able to adapt to low-water periods, Duncan says. Cables attached to underwater concrete anchors hold it in place, and a system of winches is used to move it in response to changing lake levels. That keeps the marina’s rental and private boats, including one owned by crooner Wayne Newton, in plenty of water.

Guest Services operates Temple Bar’s concessions via year-to-year contract extensions, which Duncan notes can make it difficult to make long-term improvements to the site’s aging facilities. But now, there’s reason for optimism. This past July, the recreation area released its plan for maintaining visitor services amid declining water levels. While nothing is set in stone, the plan indicates that ending the Temple Bar concessionaire contract is not in the Park Service’s short-term plans.

Two months later, Mike Gauthier became Lake Mead’s permanent superintendent after previously serving in an interim role. Duncan says Gauthier was instrumental in securing funding during a recent period of exceptionally low water. That, plus the release of the low-water plan, has Guest Services discussing potential upgrades at Temple Bar, and the Park Service has committed nearly $1 million for equipment needed to move the marina during periods of drought. “It was nice to have that commitment,” Duncan says, adding that the Park Service has been a good partner. “They’re not going to turn around and close us down,” she says.

Already, the Mobi-Mat is bringing some boaters back, she says. Once word spreads, more will follow. And Duncan, Elmore and other people who love Temple Bar hope visitors will keep following that paved road to a desert oasis that somehow feels both intimately familiar and entirely unexpected. “It’s so peaceful,” Duncan says. “People come out here, and they don’t get it. And after one night under the stars or out on the lake, they get it.”

Elmore adds, “It’s a gorgeous place.” And what he says a little later is about the lack of cell service, but it’s about more than that, too: “It’s not for everyone. But it’s for a lot of people.”

To learn more about the amenities and recreation opportunities at Temple Bar, call 855-918-5253 or visit templebarlakemead.com. To learn more about Lake Mead National Recreation Area, call 702-293-8990 or visit nps.gov/lake.