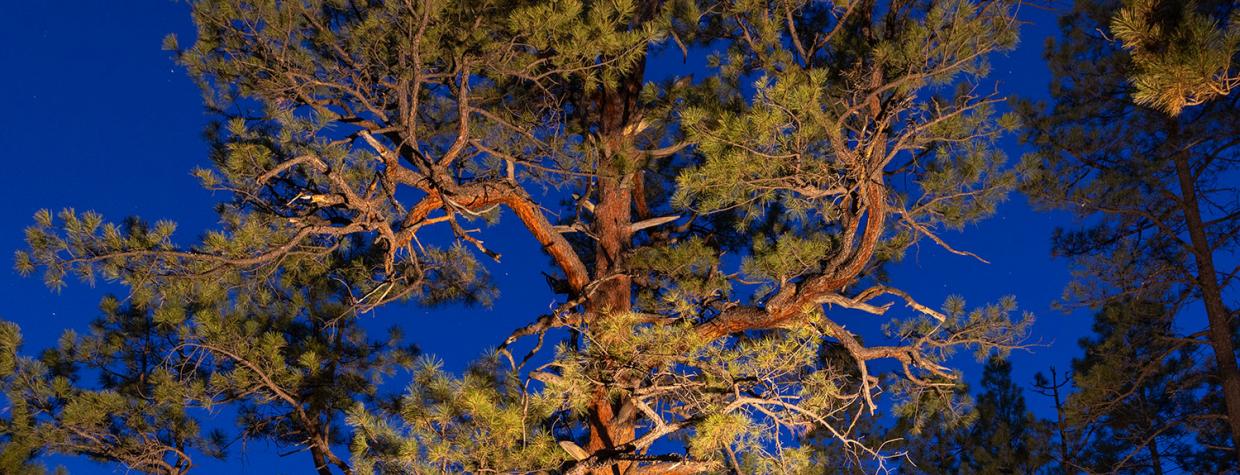

I call her the grandmother tree. She lives near the top of Mars Hill in Flagstaff, on a slope well away from established trails. Far bigger than any other ponderosa pine around, she is about 150 feet tall and, according to scientists I’ve consulted, at least 400 — or maybe even 500 — years old. Copper-colored bark wraps around her trunk like connecting puzzle pieces. Her lower branches are massive and barren, and they extend out like arms. When the rest of the forest goes dark around sunset, her crown shimmers gold as the uppermost branches manage to catch the day’s last light.

I first noticed this forest elder in 1996, when I was pregnant with my son, Austin, and had wandered off the Mars Hill trail system in search of solitude. As first-time motherhood reshaped my world, visiting the grandmother tree became a daily ritual, an emotional touchstone. Day after day, year after year, decade after decade, I trekked up Mars Hill and felt my heart sing every time I caught sight of her ancient, radiant trunk coming into view.

Austin grew from a child to a teenager to a college student. I got married and then divorced. I cared for my mother with dementia until she died. I was a university professor and taught four classes a semester for 17 years. I wrote dozens of stories and four books. The population of Flagstaff nearly doubled. And the grandmother tree stood steadfast, always ready to greet me with open arms. Sometimes I visited her multiple times a day when I needed extra support.

Each morning, as I sipped tea and looked out across the backyard of my Flagstaff home, I relished the view just a quarter-mile away, where emerald-green ponderosas blanketed Mars Hill. I felt like I was living in paradise.

But it turned out that paradise was increasingly expensive, and while I was grateful for many things about my life, the decades-long struggle to support myself and my son in the growing mountain town of Flagstaff had taken a toll on my health. After being diagnosed with an unexplained heart condition in 2019, I went through a battery of tests. The cardiologist told me my heart was structurally sound and I was otherwise in excellent health. “It must be from stress,” he said. “Is there anything you can do to reduce it?”

By February 2020, I still was having cardiac symptoms despite a lot of hiking, meditating, yoga, and giving up alcohol and caffeine. The pandemic was predicted to soon descend on the United States and monopolize access to medical care. It was no time to have heart trouble.

One afternoon, on a hike up Mars Hill with my dog, Sunny, I paused as always to greet the grandmother tree. A solution to stress reduction suddenly came to me: I had to move. If I lived somewhere with significantly cheaper housing, I wouldn’t have to work multiple jobs.

I looked around at the trees that had become family to me — a hillside filled with towering ponderosas gathered like a choir. They sang every time Sunny and I walked among them. Squirrels and ravens chimed in from high branches. And the grandmother tree was the seasoned expert in these woods, possessing the knowledge for living a long, vibrant life.

But was she now suggesting that I leave? I pressed my hand against her rough bark. Under the urgent circumstances, I could imagine giving up the house where I’d lived for 16 years, and my teaching job, and even my community of friends. But how could I get by without this forest?

Until the very real prospect of moving arrived, I’d taken access to Northern Arizona’s abundant ponderosa pines for granted. These trees had become a part of me — not just the grandmother but also others that had provided refuge over the years.

Although I’d been around plenty of other species of trees in other places during my lifetime, ponderosas were the steadying force, the ever-present beacons of calm in an otherwise hectic world. What was it about these trees that I cherished so much? And could my heart safely live apart from my beloved ponderosas?

Pinus ponderosa is the most widely distributed pine species in North America. It’s found in 16 Western states, and its habitat extends from British Columbia to the Sierra Madre ranges in northern Mexico. But the largest contiguous ponderosa pine forest is in Arizona. This belt of evergreens occupies some 2.6 million acres and stretches from the New Mexico state line to the South Rim of the Grand Canyon. It ripples across the White Mountains, the Mogollon Rim and the Coconino Plateau. The ponderosas pause briefly at the Canyon’s mile-deep gorge, then resume their ecological reign on the North Rim before sprawling into Southern Utah.

Ponderosa forests are also found in the upper reaches of Southern Arizona’s “sky island” mountains. They cling to the ridges of the Superstitions and are abundant in the Bradshaws. Ponderosas are built for aridity, drawing most of their moisture from winter snowpack and summer monsoon storms. Although the paloverde is Arizona’s state tree, there’s good reason to argue it should be the ponderosa instead. When I first moved to Arizona in the early 1990s, my knowledge of trees came from growing up in the Big Thicket of East Texas. The longleaf pine forest around my childhood home had been clear-cut several times over. All the trees were the same age, the same size and destined to be made into telephone poles at the local creosote plant.

During my early days exploring the Grand Canyon State, my partner, Mike, and I strung our hammocks between giant ponderosas in Chevelon Canyon on the Mogollon Rim, backpacked in the wild forest of the Blue Range and car-camped among ancient trees on the North Rim. I had never seen pines with such distinctive personalities. It was as if the old-growth ponderosas were our campsite companions, each sporting a different hue of amber- or copper-colored bark and a different array of twisting, muscular branches.

I mistakenly thought the colorful, aromatic trees were a different species from the smaller, black-barked pines in the forest. But they all were ponderosas. After 180 to 200 years, a ponderosa’s trunk begins to transform from black to reddish-brown or gold, earning the “yellow belly” nickname. The maturing process also produces chemicals in the bark called terpenes, which give the ponderosa a distinctive aroma. Debating whether a tree smelled like vanilla or butterscotch was a favorite pastime among my Arizona hiking companions.

After a few years of longing to live in the forest instead of the desert, Mike and I finally made the move to Flagstaff in 1995. We got married, had Austin and immersed ourselves in all the pleasures that came from being in the largest contiguous ponderosa pine forest in the world.

But there was trouble in the forest, and a Northern Arizona University forestry professor named Wally Covington was trying to sound the alarm. By the mid-1990s, after conducting research in Northern Arizona for two decades, Covington warned that the trees had become a massive tinderbox. He argued that a healthy ponderosa pine ecosystem relies on regular, low-intensity wildfires — a fire regime that had been halted since the mid-19th century, when European settlers arrived in Northern Arizona. Covington’s research showed that fires swept across the forest floor every few years in pre-settlement times, preventing an abundance of young saplings. Under pre-settlement conditions, there were about 23 ponderosas per acre. By the mid-1990s, that number had exploded to more than 800 trees per acre.

In addition to trying to convince land managers that fire needed to be reintroduced to the ecosystem, Covington lobbied on behalf of the old-growth ponderosas — the grandmothers. For more than a century, the timber industry had been cutting the biggest pines first, since they were the most valuable. While most forestry professionals at the time estimated Arizona’s biggest ponderosas were about 250 years old, Covington and his colleagues proved the trees could often be 700 or even 800 years old. Basically, they were irreplaceable. These ancient trees were a kind of keystone species that everything else in the ecosystem revolved around.

By the early 2000s, Covington’s predictions about unnatural crown fires destroying ponderosa forests and threatening towns such as Flagstaff were starting to play out. That got the attention of Congress, and the Ecological Restoration Institute was established at NAU in 2004, with Covington as director. Its mission was returning Northern Arizona’s ponderosa forests to pre-settlement conditions by removing smaller trees and letting the grandmothers have some space — at least in places where old growth remained.

U.S. Forest Service workers soon were going after the doghair ponderosa thickets on Mars Hill, atop the adjacent Observatory Mesa and on public lands all around Flagstaff. The forest hummed with chain saws. Smoke from burning slash piles wafted across town. After 150 years of seeing ponderosa pines be treated like an agricultural crop, the elder trees were finally getting the respect they deserved. The forest opened up. And I could almost see the grandmother tree from my backyard.

“There is something spiritual about being with old trees,” Covington muses. “It is self-transcending.”

A towering yellow belly with golden bark rises before us. The forest elder is next to the horse racetrack at Flagstaff’s Fort Tuthill County Park. Although people pulling into the track’s gravel parking lot might never suspect it, the ponderosa took root in 1641, according to Covington’s tree ring dating.

We’re bundled up in coats and scarves on a freezing January afternoon. I’m visiting Flagstaff from Cortez, Colorado, where I now own a house with no mortgage. The strategy to uproot from Flagstaff to make my life more manageable is working: My heart has been symptom-free for more than a year.

Covington has graciously agreed to meet me for a walk in the woods so I can better understand my favorite kind of forest. After 44 years at NAU, Covington retired in January 2020, at age 73. But he remains an enthusiastic champion for restoring the health of ponderosa pine forests. Covington has taken everyone from elementary school children to congressmen on tours of areas, such as Fort Tuthill, that he helped return to pre-settlement conditions.

As we traipse through crusty snow, Covington picks up the tip of a pine twig that’s been chewed by an Abert’s squirrel. “We call these corncobs,” he says, holding what the squirrel discarded after chowing down on the twig. The Abert’s squirrel is a creature of ponderosas, nesting in the trees and eating the wood, seeds and fungi. In return for this sustenance, the squirrel spreads ponderosa seeds, keeping the forest regenerating. “There were fantastic co-evolutionary relationships going on in ponderosa pine forests that had been sustained for millions of years until European settlers came along,” Covington says.

The old-growth trees continue supporting the ecosystem even after they die. More than 100 species of birds nest in standing ponderosa snags, and fallen deadwood provides critical habitat for numerous species, including new ponderosas that take root in a decaying elder.

Thanks to Covington’s influence, much of the ponderosa forest immediately surrounding Flagstaff has been restored, although there’s no way get back the old growth that was logged and now is forever missing from the ecosystem. However, Covington says, only 2 percent of ponderosa pine forests in the West have been thinned. The infrastructure bill recently signed into law provides funding to help pick up the pace. “It is a race against crown fire,” Covington says.

I ask Covington if he has a favorite neck of the woods. “Just about any place with old-growth trees — the more, the better,” he says. “Old is important, especially the older I get.”

After saying goodbye to Covington, I hike up Mars Hill to visit the grandmother tree one last time before leaving town. I’ve been living in my new home for a year and a half, but as I approach the ancient tree, just as I have more than a thousand times before, it feels like I never left. And in the context of an old-growth ponderosa’s life span, almost no time has passed at all.

Even though I now live 260 miles away, the fact that the 400-year-old grandmother is here — and could live for another three or four centuries — helps me keep day-to-day concerns in perspective. This tree knows things that humans don’t. Plus, my new work schedule allows me to visit Flagstaff often. I co-evolved with this forest as my life events accumulated like tree rings. I’ve come to understand that these ponderosas are part of me, regardless of whether or not I’m physically among them.

I wrap my arms around the grandmother’s 6-foot-diameter trunk and give her a hug. She smells like vanilla. Then, I crane back to take a photo, unable to get all of her husky branches and sky-high crown in the frame.

I send the photo to Covington, who’s curious about this grandmother of mine. Covington quickly responds. He knows a wise elder when he sees one.

“That’s a very noble veteran,” he replies.