If a visitor to the Louvre walked up to the Mona Lisa with a can of spray paint, they’d be immediately tackled by security guards. But what about a vandal approaching a rock art panel, dating back 1,000 years, in a remote canyon in Sedona’s Red Rock Country?

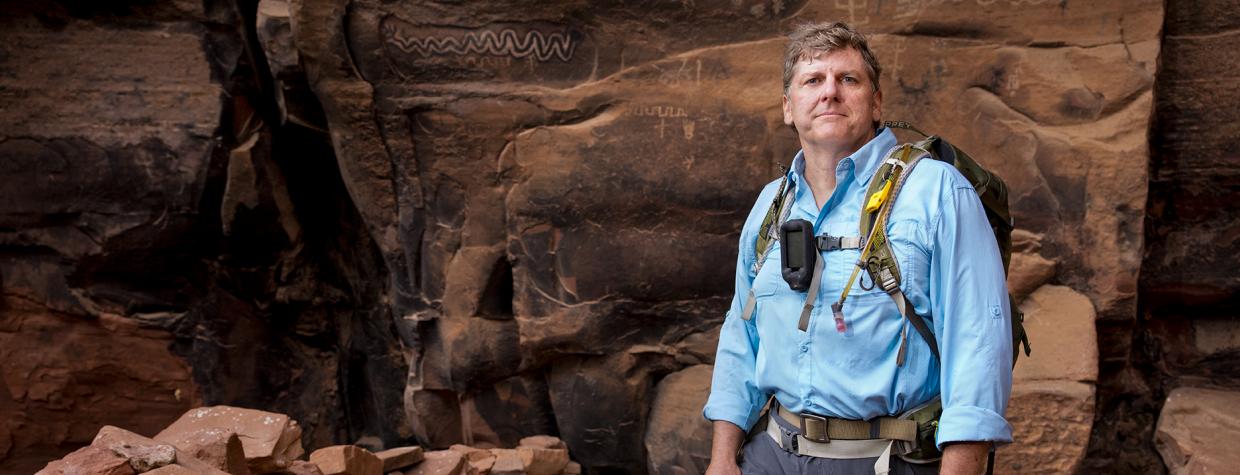

There’s no high-tech security system for the many petroglyphs in the Coconino National Forest’s Red Rock Ranger District. But there is Scott Newth (pictured). And, through sheer force of will, he’s finding new ways to give American Indian rock art the respect and protection it deserves.

Newth and his wife, Daniela, moved to Sedona from Florida 15 years ago. He was a successful entrepreneur who retired at age 36 after selling a company he co-founded. The couple chose to live in Sedona for its hiking opportunities, but Newth is also a history buff, and he was drawn to the rock art panels he saw along the area trails. “I became obsessed,” Newth says, and his curiosity turned into full-time volunteering for the national forest.

Archaeologists have found evidence of human activity in the Sedona area dating back 13,000 years, and the fertile Verde Valley was heavily populated by the Sinagua people, ancestors to some Hopi clans, from about A.D. 600 to 1400. Perhaps due to its abundance of sheltered alcoves and sheer sandstone walls, the Red Rock Ranger District harbors one of the highest concentrations of pictographs in the state.

Wearing knee-high Kevlar gaiters to protect against rattlesnakes and thorns, Newth began bushwhacking through the 550,000-acre district almost daily, scrambling into hidden alcoves in search of rock art panels. Every time he found what he believed was an undocumented archaeological site, he made photos and sent a report to Peter J. Pilles Jr., the forest’s lead archaeologist. Newth figured once the forest was made aware of the valuable resources under its jurisdiction, steps would be taken to protect them. But he soon learned how slowly the wheels turn in bureaucracy. His reports filled an ever-expanding binder in Pilles’ office, but little action resulted.

“We can’t just run out and do something,” says Pilles, who’s been overseeing the forest’s archaeology program for 46 years. “The [U.S.] Forest Service has great intentions, but we have time and funding problems. The only specific funding we have to protect archaeological sites is for law enforcement officers, and we only have two of those positions covering the entire district.”

Pilles says his agency relies heavily on volunteers to fill the manpower gaps. Organizations such as the Arizona Site Steward Program, the Arizona Archaeological Society and Sedona’s Friends of the Forest help monitor frequently visited sites, offer interpretation to visitors and remove graffiti. But the forest can only ask volunteers to monitor known sites — that is, those that have gone through the Forest Service’s rigorous documentation process. “Properly documenting a site is a lot of work,” Pilles says. “It is a rare individual, especially a volunteer, who is willing to do it.”

Newth was unfazed. After Pilles trained him in the process, he assembled a team of eight core volunteers, as if he were forming another startup. “Everyone has a respective expertise,” Newth says. “I have two people who focus on ceramic sherds. I do rock art. I have another volunteer who is really into lithics.”

Over the past four years, Newth’s team has recorded more than 60 archaeological sites, allowing the forest to officially recognize and better protect them. That’s out of more than 300 sites previously unknown to Forest Service archaeologists that Newth has “discovered” in the Sedona area.

Another of Newth’s initiatives is installing signs and motion sensor cameras at remote sites that suddenly receive heavy visitation because they pop up on social media or Sedona tourism websites. Working in partnership with the district, Newth received private funding for signs that have been put up at more than 60 sites, along with cameras at the most imperiled locations.

Each sign reads, in part: “Please respect the sanctity of this area. Beyond this point lies a site of traditional significance to descendants of Native Americans whose ancestors made this area their home for thousands of years.” It also instructs visitors how to help preserve the site by not littering, picking up artifacts or touching the rock art.

Newth says many tourists arrive at the rock art panels with no information about what they’re looking at beyond the GPS coordinates on their phone. “You need to let people know somebody cares enough about this site to monitor it,” he says. “I want people to value these places. An element that is a thousand years old can be destroyed in one second by someone who doesn’t care.”

Newth’s favorite rock art panel is one he first visited 15 years ago, when the main way Sedona hikers found out about such sites was through word-of-mouth. It’s at least 100 yards long and tucked into an alcove that preserves hundreds of drawings ranging from the Archaic period to the 20th century. Above the remains of ancient agave roasting pits are creations by prehistoric hunter-gatherers, Sinaguans and Yavapais. When Leonardo da Vinci was painting the Mona Lisa in the 16th century, Indigenous holy men were painting on the alcove’s wall. “It is the most important [rock art] site in Coconino National Forest,” Pilles says.

Signs and motion cameras were installed at the site four years ago, and Newth says visitors have cleaned up their act. There’s less graffiti, and people are no longer leaving behind geocaches, candles and other items. Newth recalls being moved when he took members of the Hopi Tribe to the site and they thanked him for putting up the signs.

“They recognized some of the elements on the panel as their deities that are still part of their ceremonies today,” Newth says. “That’s why I call these sites living ancestral churches.”

To learn more about volunteering in Sedona-area archaeology programs, contact the Red Rock Ranger District at 928-203-7500 or visit fs.usda.gov/coconino.