If you’re too young to remember, or if maybe the ’70s are just a blur, here’s some of what was happening back in February 1974: The Way We Were by Barbra Streisand was the No. 1 song in America, Blazing Saddles was making its debut on the big screen, and Gore Vidal’s Burr was in the middle of a long run at the top of The New York Times’ best-seller list. That same month, Jerry Jacka stormed the pages of Arizona Highways.

Arizona Highways

“They gave me all four covers, and other than a small story on Lon Megargee, I had every photograph in the magazine,” Jerry explained, with the same enthusiasm he might have shown had he been recounting the birth of his two children or the discovery of the Lost Dutchman’s gold. “I couldn’t believe it.” (Insert Jerry’s laugh, which had the resonance of Santa’s “Ho! Ho! Ho!”)

He told me that story last summer at his home on the Mogollon Rim, but in the interest of full disclosure, it wasn’t the first time I’d heard it. Jerry was a wonderful storyteller, and some of his stories, he figured, were worth telling again and again, especially this one. Each time he told it, you could see that he was proud, and maybe still a little surprised by the whole thing, even though it had been decades since the issue was published.

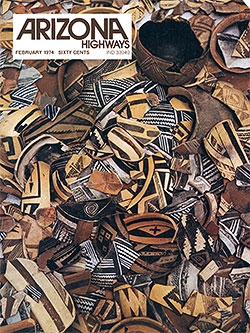

That issue, which sold for 60 cents on the newsstand and featured one of Jerry’s images on the cover, was focused on “the treasure of prehistoric pottery” in Arizona. It wasn’t unusual in those days, or even now, to have an issue dedicated to a single subject. In fact, that was the norm throughout much of our history. What was unusual was to give almost every page to a single contributor.

“The concept for this special issue was born when Jerry Jacka came to us in the summer of 1972 with a proposal we could not ignore.” That’s the first sentence of an editor’s note in the February 1974 issue. The editor at the time was Joseph Stacey, who’d recently taken the helm from longtime Editor Raymond Carlson.

“On pure speculation,” Mr. Stacey continued, “with no commitment from Arizona Highways, [Jerry] would undertake to photograph the most important examples of Arizona’s prehistoric pottery. Jerry Jacka is no stranger to our pages. His first photograph was reproduced in July of 1958. Arizona’s Indian country is his first love. He knows the people, the land, and is respected and recognized as one of our best informed laymen on Indian history. The photographs credited to Jerry Jacka in this issue were part of a special selection chosen from almost 500 transparencies.”

In the age of megapixels and terabytes, 500 images isn’t worth noting, but in the days of film and processing, that kind of volume was a tremendous investment, with no guarantee that any of those images would show up in print. Nevertheless, Jerry went to work. Meanwhile, world politics began unfolding in his favor.

Again, if the ’70s are just a blur, here’s what was happening: In October 1973, Arab oil producers had cut off exports to the United States as a way of protesting American military support for Israel, which was at war with Egypt and Syria. The embargo led to inflated gas prices and long lines at gas stations. In addition to making it more expensive to produce magazine stories, the “energy crisis” devastated the tourism industry and, subsequently, the mission of Arizona Highways, which is to promote travel — if fuel is unaffordable or unavailable, it’s hard to convince readers to throw their kids in a station wagon and make a road trip to the Grand Canyon. In response to what was happening, Mr. Stacey began looking for content beyond traditional travel journalism. And he found it.

Known today as the “turquoise issue,” the January 1974 edition was dedicated entirely to the history and culture of turquoise jewelry, as well as the talented Native Americans who fashioned it. It was, and still is, the biggest-selling issue in the history of Arizona Highways — it sold more than a million copies.

The sequel to that blockbuster, in February 1974, is what’s known today as the “Jerry Jacka issue,” which was based on those 500 transparencies. And something more.

“I also submitted a little write-up, along with a self-portrait,” Jerry said. “I couldn’t believe it when I saw the issue for the first time and realized that Joe had even included those. I’d gone down to the magazine on my lunch hour, and I was absolutely aghast all the way back to work. I was lucky I didn’t get into an accident, because I wasn’t looking at the road, I was looking at the magazine.”

In the footsteps of Mr. Stacey, we’re republishing that little write-up once again, along with some of the images that ran in the issue. As you can see, Jerry liked to stage prehistoric pottery all over Arizona. On rocks and tree stumps, in the shadow of volcanoes, on the walls of ancient ruins. Of course, you could never get away with that today — the risks are too high — but in the ’60s and ’70s, that’s how it was done, at least by Jerry, which makes our February 1974 issue, the “Jerry Jacka issue,” even more beloved and unique.

ARIZONA’S PREHISTORIC POTTERS: ARTISANS OF THE PAST

by Jerry D. Jacka

Are you among those who pass through our museums and national monuments, taking for granted the many ancient works of art on display? If so, I suggest you take advantage of the next opportunity to take a second look. Look not with the simple objective of seeing only relics of the past, but open your eyes to the artistry displayed in these prehistoric artifacts.

Arizona’s prehistoric Indians share the distinction of being among the finest artists to have lived on the face of the earth. For several centuries prior to the coming of the first Spaniard, these ingenious people applied their creative talents to many aspects of their everyday life. Of all their known art forms, pottery has best survived the centuries and truly demonstrates the ability of these craftsmen-artists.

These prehistoric Arizonans blend simple colors, basic geometric designs and life forms to create their beautiful wares. The beauty of this Native American art is found not only in its decoration or painted design, but also in the shapes of many vessels, which present truly striking forms of art.

To fully appreciate these ancient vessels, one should consider the manner in which they were made. Obviously, a local art supply store was not available for the purchase of clay, paints and brushes. All of these were manufactured by the potter from raw materials. Clay was mined from nearby (and sometimes not so nearby) deposits, paints were manufactured from plants and minerals, and frequently water had to be transported over great distances to make the clays, slips and paints. Keep in mind that neither the potters wheel nor the kiln were used. In spite of these hardships, during the 10th through the 16th centuries highly decorated pottery was manufactured in quantities that would “boggle the mind.” These vessels were made with such skill that many have survived the centuries retaining all of their original beauty.

Although the shape, design and chemical composition of prehistoric pottery has great scientific value to the anthropologist and archaeologist, it also shares a similar status to the person who appreciates fine art. Some of the finest prehistoric pottery in the world has been found in Arizona, and many artists, representing a variety of modern cultures, continue to copy its style.

I invite you now to explore prehistoric pottery as an art form in the accompanying photographs. With few exceptions, every piece of pottery appearing in these photographs came from sites of prehistoric dwellings in Arizona which were inhabited prior to the year 1500. If these photographs whet your appetite to see and learn more, I suggest that you visit the many museums and national monuments in Arizona.