Starting in the 1870s, the explorers and anthropologists who stumbled upon their enigmatic ruins called them “the Cliff Dwellers.” In December 1888, while out chasing stray cows on top of Mesa Verde, ranchers Richard Wetherill and Charlie Mason discovered the biggest ruin of all, which they called Cliff Palace. The same day, Wetherill rim-walked another canyon and found Spruce Tree House.

Mesa Verde National Park, in Southwestern Colorado, remains the region where tourists are most likely to encounter the alcove-guarded villages wrought by the ancients out of shaped sandstone blocks, wooden beams and sticky mud. But you can tour Cliff Palace today only as part of a group, with up to 50 fellow visitors, guided through the site by a ranger in an hour flat.

All across Northern Arizona, however, the canyons enclose cliff dwellings built by the close kin of the people who crafted Cliff Palace and Spruce Tree House. The finest of them all is Keet Seel, one of the twin jewels of Navajo National Monument. It was discovered in 1895 by the same two ranchers who found Cliff Palace, along with Richard’s brother, Al — the Wetherill clan having converted themselves into competent self-taught archaeologists.

Cliff Palace, still regarded as the largest cliff dwelling in North America, was once thought to contain 220 rooms, though more rigorous research in recent years has reduced that estimate to as few as 150. Keet Seel is composed of at least 150 rooms ranged across a lordly shelf some 80 feet above the canyon floor. Overzealous reconstruction, starting in 1909, made something of a botch of Cliff Palace. But Keet Seel was restored in the 1930s by archaeologists with a lighter touch, and it looks today very much as it must have in A.D. 1280. To reach Cliff Palace takes only a five-minute stroll from the park’s paved loop road. Keet Seel, by contrast, requires a 17-mile round-trip hike through magnificent canyons lined with piñon pine and juniper trees.

Who were the ancients who built these wonders, and where did they go?

At the 1927 Pecos Conference, the first formal gathering of Southwest archaeologists, Alfred V. Kidder proposed the term “Anasazi.” We now know that the architects of the cliff dwellings (and of thousands of other open-air sites not preserved under arching alcoves) flourished for millennia all across the Colorado Plateau, in what today are Southwestern Colorado, Northwestern New Mexico, Southern Utah and Northern Arizona. But the people abandoned that homeland en masse and for good just before A.D. 1300. The last tree-cutting date found anywhere in an Anasazi ruin on the Colorado Plateau is A.D. 1286, from a pair of timbers — one at Keet Seel, another at the Navajo National Monument’s second gem, Betatakin. Drought, famine, deforestation, the hunting to near-extinction of big game, and, perhaps, religious renewal contributed to the abandonment, but it remains the central Anasazi mystery.

“Anasazi” is what the ruin-builders were called by the Navajos, who came to the Southwest at least a century after the abandonment. The term, which means “ancient enemies” or “enemies of our ancestors,” perfectly captures the ambivalence the Navajos felt toward their predecessors, whose ruins were redolent of death and spiritual danger. “Anasazi” was the term uniformly used by archaeologists for seven decades after the first Pecos Conference. But, in the 1990s, a new generation of politically correct scholars, reinforced by Puebloan activists, lobbied hard to extinguish the term, arguing that it was ethnically pejorative in the same way that names such as “Eskimo” and “Indian” were. In its place, the PC folks proposed “Ancestral Puebloans.”

The ancients on the Colorado Plateau did not vanish. Many of them simply migrated south and east, merging with the inhabitants of Pueblo villages ranging from Hopi to Taos. Hence the term “Ancestral Puebloans.” But I’ve never been able to swallow that awkward mouthful. The Hopi call their northern ancestors “Hisatsinom.” But that’s not the term the Zuni use, or the Acomans, or the residents of Jemez.

In any event, as a somewhat derogatory Spanish word, “Puebloan” sounds more inept, to me, than “Anasazi.” So, I go on blithely using the archaeologically precise term Kidder first proposed, even though readers write letters to editors scolding me for my backwardness.

Northern Arizona is so rich in Anasazi ruins that it was inevitable that some of the finest ones would be set aside in national parks and monuments, including Betatakin and Keet Seel, as well as White House and Antelope House in Canyon de Chelly. But parks breed bureaucracy, and popularity inevitably leads to stringent protection of the fragile and irreplaceable sites. Twenty years ago, I was free to hike into Anasazi sites in Canyon del Muerto, the northern branch of Canyon de Chelly. Today, you can hike del Muerto only with a Navajo guide, and you can look at those ruins and rock art only from a distance, with binoculars.

To visit Keet Seel, you need to get a permit in advance (limited to 20 per day), and at the ruin, you can tour only a small, cordoned-off sector with the ranger who stays at the campground below the spectacular village. During the best seasons for hiking in the Southwest — April through May, and September through October — both Betatakin and Keet Seel are shut down, because the Park Service limits visitation to the broiling heat of summer. On the ranger-guided tour of Betatakin, you can no longer enter the ruin, only stare at it from the “front door,” because the Park Service is worried that rockfall from the massive roof of the giant alcove might take out a visitor or two. Another marvel, called Inscription House, which is part of Navajo National Monument, has been closed to all visitors for decades, ostensibly out of sensitivity to the Navajos across whose land you might traipse to get to the ruin. However, I’m convinced it’s because its location, 15 miles west of the monument headquarters, would make it a bureaucratic nightmare to supervise.

Over the past 25 years, I’ve worked out my own solution to the dilemma of communing with the Arizona Anasazi. It has everything to do with the Navajo Indian Reservation. On dozens of forays lasting from one day to eight, many of them solo, I’ve pushed into the backcountry in search of ruins and rock art. To hike anywhere on the reservation, you need to get a permit from the Navajo Nation headquarters in Window Rock. That small obstacle, and a nagging discomfort about entering what feels to some like a Third World hinterland, prevents the vast majority of Anasazi devotees from setting off into such splendid wildernesses as Navajo Canyon or the Rainbow Plateau. It’s true that if a traditional Navajo finds you walking across his land, a piece of paper from Window Rock may carry little weight. But, even though I’ve sometimes been stopped and asked what I was doing, I’ve never had a Navajo turn hostile or order me to go away.

On none of those trips have I ever run into another Anglo. But I’ve discovered so many obscure and exquisite ruins and sprawling panels of petroglyphs and pictographs that I can’t keep them all straight in my memory. Those days have provided some of the keenest joys of my life.

The cliff dwellings mostly date from the 12th and 13th centuries. Their pristine preservation is due to the overhanging cliffs that protect them from rain, snow and wind. Yet, though we see the ruins as beautiful, they were born not so much of an aesthetic impulse as out of fear. In the hard times leading up to the abandonment, the safest place to live, and to guard your food supply, was on high, defensible ledges. For decades, archaeologists postulated that the enemy that drove the Anasazi off the Colorado Plateau was one of several nomadic tribes migrating into the Southwest — Utes, perhaps, or Comanches or Navajos. But the best research now indicates that those nomads did not enter the Colorado Plateau until after a.d. 1300.

It was the Anasazi themselves who were the enemy. The bad guys were the dwellers in the next valley over, who, having run out of corn and beans, were determined to raid and steal yours.

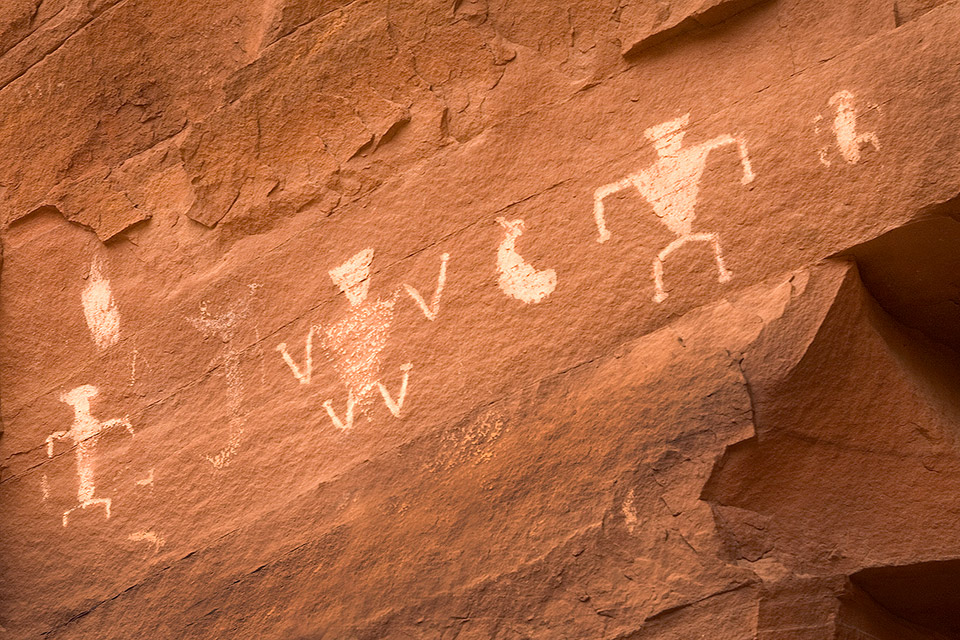

Rock art, on the other hand, spans a vast chronology dating back into the Archaic period, as early as 6500 B.C. You cannot assume that the petroglyphs at a site were carved by the same Anasazi who built the room blocks — they could have been chiseled thousands of years before, when the ancients themselves were still nomadic.

The other great boon of hiking on the reservation is that the artifacts are still mostly in place. On Cedar Mesa in Utah — as rich an Anasazi domain as any in the Southwest — decades of visitors have all but denuded the sites of potsherds and chert flakes, even though the pilfering of a single piece of molded clay has been illegal since 1906. One imagines each otherwise well-intentioned hiker picking up a pretty shard of Mesa Verde black-and-white and sticking it in his pocket, thinking to himself, I’ll just take one. They’ll never miss it.

The Navajos, on the other hand, regard the stuff left behind by the Anasazi as carrying some of the danger of the ruins themselves. The possessions of the dead are not to be messed with. Thus, I’ve spent many happy hours in backcountry canyons on the reservation, finding scatterings of painted shards, flakes ranging in color from milky-white chert to black obsidian, arrowheads and atlatl darts, manos and metates for grinding corn, and even the occasional stone axe head. I pick up each object, turn it over in my fingers, try to conjure up the artisan who shaped it and drop it back where I found it.

A few vignettes from my search for the Arizona Anasazi — though I will here indulge in a topographic vagueness that may annoy some readers. It’s a no-no among Anasazi enthusiasts to give directions in print to ruins and rock art that have managed to stay obscure and little-visited. Sadly, some of the finest of these out-of-the-way prodigies are starting to pop up on the Internet, complete with GPS coordinates. I say instead: Pick a canyon, get your permit, go out and look. You won’t be disappointed.

Three years ago, a pair of friends and I spent two days hiking the length of a 13-mile-long canyon somewhere south of Canyon de Chelly. Near its upper end, we spent hours gazing at and photographing a 30-room ruin that archaeologist Stephen Jett calls the best-preserved in all the Southwest. The Navajo Nation has forbidden entry to the site, and we abided by that stricture. Then, downstream, we stumbled upon one panel after another of graven and painted images: duck-headed humanoids, atlatl symbols, bighorn sheep, zigzag snakes, spirals, handprints, and all kinds of abstract designs whose meaning is forever lost. I’m sure we found only about half the art that canyon contains.

The backcountry may be wild, but it’s full of Navajo cattle and sheep. On my third day solo in a convoluted side canyon, some 15 years ago, I walked through a small room block, disgusted by the cow pies everywhere and by the miscellaneous junk the ranchers had left behind. Spotting what looked like a metal ring lying on the ground, I bent over to pick it up, but it didn’t budge. Slowly, I realized that it wasn’t metal at all. I carefully brushed away the dirt surrounding it until I uncovered a perfectly intact mug, complete with its coffee-cup handle, painted in the gorgeous orange-and-black patterning called Tusayan Polychrome. Somehow, the cows had failed to crush it. I pondered tucking it away in a safe niche above the ground, but, in the end, I covered it back up with dirt, leaving it right where it had lain for 800 years.

Other glories: a ruin 5 miles in with the strangest Anasazi structure I’ve ever seen — a massive wooden platform 40 feet up a huge, flaring chimney, wedged tight against the bulging walls like some vision-starved shaman’s lookout post. Many a granary sealed tight into a tiny cubbyhole as high as 100 feet up an overhanging wall. Hand-and-toe trails gouged into near-vertical cliffs by daredevils with quartzite pounding stones — shortcuts to the mesas above that I would never dare to scale today. A free-standing butte in the middle of a flat plain — really, almost a pinnacle — with 20 rooms spread across every nook of its summit, and shards and flakes everywhere.

And, of course, the Lost City of the Lukachukais. The old legend had it that, in 1909, a pair of Franciscan missionaries out of Farmington, New Mexico, rode west into Arizona to convert the heathen Navajos. Stymied by a sandstone labyrinth, they came to a canyon rim and beheld a huge ruin in the alcove opposite, but they had no way to get to it. It was the equal of Cliff Palace, the padres swore. But, on several subsequent journeys, they could not find it again.

In the 1930s, the great archaeologist Earl Morris spent months looking for the Lost City. If he found it, he never mentioned his discovery in print.

In 1996, in the course of a six-day ramble with friends into the Lukachukais, I think I found the Lost City. It’s no Cliff Palace, but it’s a stunning ruin with one of the finest intact kivas I’ve ever seen. And it’s really hard to get to. But that’s another story.