You don’t need a Ph.D. in anthropology to decipher the names of many of Arizona’s landmarks. The Grand Canyon is just that. The Vermilion Cliffs radiate a deep red at sunset. The Salt River flows over large sodium deposits. And South Mountain once marked the southern boundary of the Phoenix metro area.

But there also are plenty of landmarks named after people, and the reasons for these honorary designations are often blurred by the passage of time and patchy historical accounts. Agassiz Peak, Arizona’s second-highest summit, fell into this ambiguous category until a group of determined Indigenous students started asking questions.

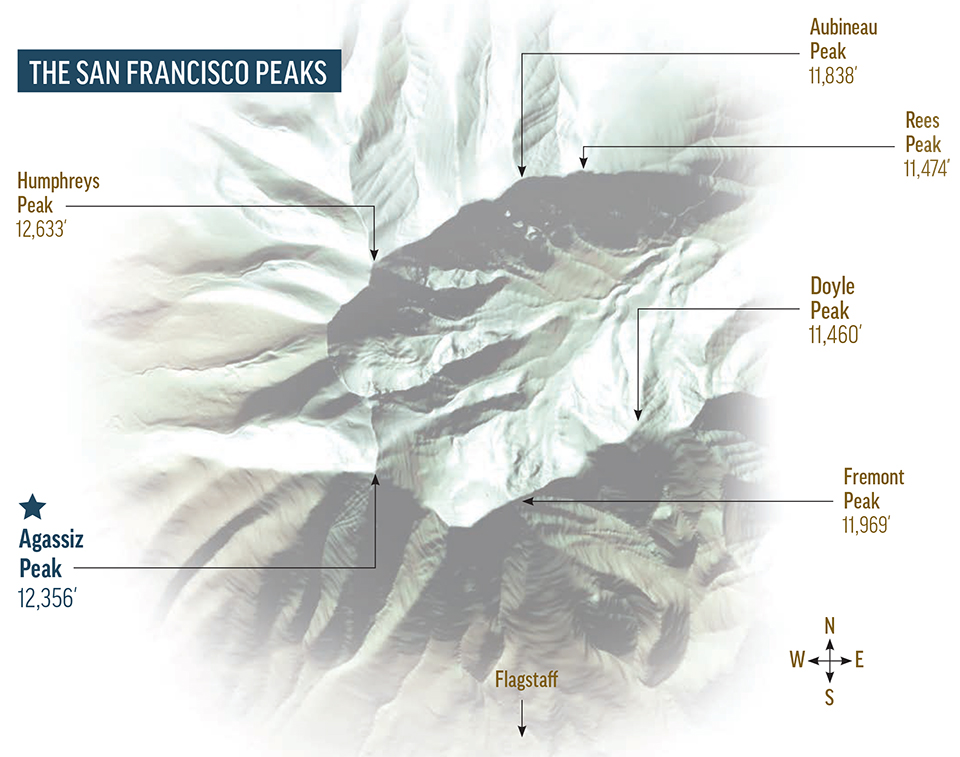

Agassiz Peak is part of the San Francisco Peaks, a ring of mountains crowning a dormant volcano just north of Flagstaff. At 12,356 feet, Agassiz is slightly shorter than nearby 12,633-foot Humphreys Peak. And while Humphreys — named in 1873 for U.S. Army General Andrew Atkinson Humphreys — claims the high point of the Peaks (and Arizona), it’s south-facing Agassiz that dominates Flagstaff’s skyline.

Robert Breunig, the former executive director of the Museum of Northern Arizona, does hold a Ph.D. in anthropology. He says Agassiz Peak got its name in 1867, during a survey expedition led by another Army general, William Jackson Palmer. The federal government was searching for a viable transcontinental railroad route along the 35th parallel, and Palmer was struck by the towering summit near the community that would become Flagstaff.

“Scientists were like rock stars back in those days,” Breunig says. And even though Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz had never set foot in Arizona or laid eyes on the mountain, Palmer decided to name the peak in honor of the famous naturalist and professor who’d founded Harvard University’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. A Swiss immigrant and contemporary of Charles Darwin, Agassiz had received acclaim for his numerous scientific studies in the mid-19th century, which ranged from glaciers to Amazon fish.

“Palmer just slapped a name on the map,” Breunig says. “I doubt it ever crossed his mind to ask the Indigenous people of the area what they called the mountain. The way Euro-Americans went in during that time and named things was a form of colonial arrogance. The names they chose had nothing to do with the mountain itself or its spiritual value to Indigenous people.”

The entire mountain range, named San Francisco by Franciscan friars in the early 1600s, is sacred to at least 13 tribes. In their own languages, the Acoma, Apache, Diné (Navajo), Havasupai, Hualapai, Mojave, Southern Paiute and Zuni peoples each have a unique name for the Peaks that dates to long before Europeans arrived in present-day Arizona.

But after Flagstaff was founded in 1876, the name Agassiz became synonymous with the geographic identity of the town. As the decades passed and Flagstaff grew, the reason the peak was named after a Harvard scientist faded, and whatever social inequities the name represented remained unexamined. But in March 2020, students at Flagstaff High School’s Native American Club decided to investigate Louis Agassiz’s background.

The students read about Agassiz’s scientific accomplishments and position at Harvard, but they discovered something else: that Agassiz promoted a racist, pseudoscientific theory called polygenism. According to Breunig, “It was an idea that each race was a separate species with separate divinely created origins.” Adherents of the theory ranked races based on skull measurement to suggest cranial capacity reflected intelligence, with white people at the top and Black people at the bottom — just below Indigenous people. These so-called scientific findings were used to justify segregation and other policies against people of color.

The revelations about Agassiz alarmed Native students and graduates, including Makaius Marks, a member of the Navajo Nation. “Why is this peak named after a eugenicist?” he recalls club members asking. “How come it isn’t named something more respectful?”

The students decided to address an injustice that had gone unchallenged for nearly 150 years. “We started to formulate a plan,” Makaius says. “We asked about the paperwork that needed to be filled out to change a name. Who do we need to convince?”

There were no easy answers. Unlike the 19th century frontier days, when explorers haphazardly named landmarks whatever they pleased, the geographic naming process is now tightly controlled, and multiple government agency permissions are required when the request involves public land — as it does with the Peaks, which are in the Coconino National Forest.

A yearslong effort by the students to remove Agassiz’s name from the sacred mountain would involve navigating city, state and federal bureaucracies — and even meeting with the scientist’s descendants. But what the students didn’t realize when they took on the project was that their effort to heal the past would also shape their futures.

The Native American Club at Flagstaff High has been active for more than 50 years, according to club sponsor Darrell Marks, Makaius’ father. He says the club ranges from 40 to 70 students during the school year, depending on seasonal sports activities. About a quarter of the school’s 1,600 students are Indigenous, and while the club is open to all students, it focuses on supporting Natives who want to learn about their traditions and culture.

For 46 years, the club has sponsored a well-attended spring powwow to raise money for its community service activities, which include mentoring elementary school students, providing food boxes to families in need, and helping students with college and career readiness. The club members also engage in environmental and social justice causes, which led to their 2020 investigation of Agassiz Peak.

“They moved fast,” Darrell recalls. “Within a week of learning about the history of Agassiz, they wrote letters to Flagstaff City Council members and held a public press conference about how continued use of the name harmed Indigenous people.”

The City Council was impressed by the students’ presentation. After a public process, Flagstaff changed the name of the city’s Agassiz Street to honor Wilson Riles, who was the first African-American student to attend Northern Arizona University and later worked to desegregate Flagstaff’s public schools. But when the COVID-19 pandemic forced Flagstaff High to suspend in-person learning, the students’ larger goal of renaming Agassiz Peak was put on hold until in-person classes resumed about 18 months later.

One of the students’ biggest questions: If Agassiz’s name were removed, what name would take its place? The students set out to learn what their Indigenous ancestors had called the peak — and Mashayla Tso, who was attending the University of Arizona in Tucson after graduating from Flagstaff High in 2019, stepped in to help. “I was so into my studies, and I missed home,” Tso recalls of that period in 2021.

“I was grasping for something to connect me to my roots, and I reached out to Mr. Marks for advice.”

Tso grew up on the Navajo Nation, in the small community of Hard Rock. Her family moved to Flagstaff when she was in high school, and she was an active member of the Native American Club. Darrell suggested Tso use her connections with elders on tribal land to get their input on Indigenous names for the peak.

Tso found that interviewing members of various tribes about the sacred mountain was the antidote to her homesickness. She started her research by talking with her great-grandparents who live in Hard Rock and speak only Diné. “My great-grandparents have so many stories about our homeland,” she says. “When they tell these stories, you can see in their eyes how a part of them lights up.”

When Palmer, the Army general, traveled through present-day Northern Arizona in 1867 for the railroad survey, the Navajo people had been removed from their homeland by the United States government and sent on a forced march called the Long Walk. Some 3,500 died during the trek and subsequent four-year internment at Bosque Redondo in New Mexico. Then, in 1879, barely a decade after the Diné had returned to a reservation established on a slice of their homeland, the tribe’s children — along with Indigenous children across the United States — became the first of many generations forced into boarding schools, where speaking their traditional language and practicing their culture were forbidden.

Tso found this traumatic legacy made some tribal elders reluctant to talk about their culture or recall traditional place-names that had been kept quiet for generations. And while the Diné called the entire mountain Dook’o’oosłííd, it seemed there weren’t specific names for the individual summits. But Tso learned that the Hopi name for the peak rising above Flagstaff was Oomàwki, which means “home of the clouds.” The peak’s summit was where precious moisture gathered before drifting northeast to the Hopi mesas to water life-sustaining crops. And the name Oomàwki preceded the name Agassiz by at least 1,000 years.

After Tso shared her research with the Native American Club, the students, members of a variety of tribes, were unanimously in support of the name Oomàwki. The students’ goal, Darrell recalls, became not to give the peak a new name, but to “restore the name — go back to the original.”

Darrell’s son Makaius, who had graduated from Flagstaff High in 2019 and was attending NAU, also got involved. He submitted a name change proposal, the first step in a detailed review process, to the U.S. and Arizona boards that deal with geographic names.

As the students prepared to make their case to government agencies, they met via Zoom with Lakota elder and spiritual leader Basil Brave Heart, who’d been instrumental in changing the name of Harney Peak, the highest summit in South Dakota, to Black Elk Peak in honor of a Lakota spiritual leader. “The advice Basil gave us was that changing a name is not about asserting Indigenous identity over others,” Makaius recalls. “It is a restorative practice. It is about restoring our sense of belonging to one another and to our homeland.”

Meanwhile, some 2,500 miles away on the Harvard University campus — and unbeknownst to the students — the descendants of Louis Agassiz were also engaged in an effort to reckon with their ancestor’s harmful legacy.

When sisters Susanna and Marian Moore were growing up in the 1960s and ’70s, they were told their great-great-great-grandfather Louis Agassiz was an acclaimed Harvard professor who made important scientific discoveries. “We thought Agassiz was famous because he was so smart,” Susanna says of the childhood beliefs she and her sister shared. “And his intelligence was evidence that our family was special.”

As young adults, the two women came across vague references to the views of race that Agassiz promoted, but at that time, they chose to remain ignorant of the disturbing information. “I wish I had been curious instead of letting the shame overpower me,” Susanna says. “I didn’t know how to look into it further without feeling tainted myself.”

Decades later, in 2019, the siblings’ older sister forwarded Marian a front-page story in The New York Times about Agassiz’s research at Harvard. He had commissioned daguerreotype portraits of slaves, and one of the subjects’ descendants, Tamara Lanier, was suing the university to have the images returned to her family. Susanna and Marian were appalled to learn the extent of the harm their ancestor had caused. “This time, I did not want to turn my back, but [to] go toward it,” Marian says.

The sisters and two of their nephews crafted an open letter, signed by the four of them and 41 other Agassiz descendants, to Harvard’s president in support of Lanier’s lawsuit. In the years that followed, as the lawsuit dragged on, Susanna and Marian also joined Lanier at speaking events, representing a rare partnership between a descendant of slaves and the descendants of a scientist whose work was used to justify racist practices and policies.

In 2021, news of the sisters’ advocacy landed in the email inbox of Flagstaff resident Hilary Giovale, whose son was in eighth grade at the time. Giovale had been coordinating a letter-writing effort among Flagstaff middle school students in support of the Indigenous youths’ Oomàwki campaign. She contacted the sisters, hoping to get their help; they had no idea a peak in Arizona honored their ancestor, but they enthusiastically joined the campaign. After visiting with the Native American Club students, Susanna and Marian wrote a letter that was included in the submissions to the state and federal boards on geographic names.

“We recognize that it is a complex navigation to appropriately reckon with the extremely harmful far-reaching effects of [Agassiz’s] work while still honoring his positive contributions,” the letter states. “Some bemoan the spread of ‘cancel culture’ in situations like these. We would suggest to those people that the culture that has been consistently canceled for over 500 years are the cultures of the Indigenous people whose land our ancestors have stolen. We suggest that it is past time to consult with these peoples and ask that they lead us in the restoration of the names of this and other sacred mountains.”

In October 2023, the six-member Arizona State Board on Geographic and Historic Names held a meeting via Zoom to consider the proposal to rename the peak Oomàwki. In addition to the letter from the Agassiz family, the proposal had support from Flagstaff’s mayor, tribal leaders and the Coconino National Forest’s supervisor. Makaius led the presentation on behalf of the club’s students and other Indigenous youths from Flagstaff.

A board member asked Makaius if the Oomàwki proposal had received any pushback, especially from tribes other than the Hopi who might want the peak named in their own language. “There is a shared understanding as to why it is called ‘home of the clouds,’ ” Makaius responded, noting that at public presentations, the name had always received a positive reception from both Native and non-Native people. “Oomàwki reflects the environment, the community and a spiritual connection to place,” he added.

According to David Breeckner, executive director of the Arizona Historical Society and chair of the state panel, board members were “very impressed and emotionally touched” by the students’ efforts. “All the research they did and the way they consulted tribal elders and tribal governments was very powerful,” he says.

The state board voted unanimously in favor of the proposal. But the change is not official yet: Final approval for the name Oomàwki now rests with the U.S. Forest Service and the federal board. “We hope they are continuing to work on this at the federal level and moving it forward,” Breeckner says. (Neither the Forest Service nor the federal board responded to repeated inquiries about the status of the name change.)

While the Native American Club students and their supporters are hopeful Oomàwki will soon become the official name of the peak, the communitywide process of reclaiming the name has already proven to be healing — and even life-changing. Giovale, who is white, says removing the Agassiz name in favor of Oomàwki would allow non-Natives living in Flagstaff to “establish a more honorable relationship” with the mountain. “It changes the consciousness of settlers to make us aware that we are on Indigenous land — still,” she says. “And that the mountain is sacred, a guardian watching over this whole region, rather than a resource to be exploited.”

After those many weekends spent interviewing tribal elders, Tso realized she wanted her future to be focused on protecting Indigenous culture and recovering traditional knowledge that was lost during the boarding school era. She switched her major from nursing to public management and policy, and she plans to graduate from the UA this December. She hopes to document more stories from elders — and perhaps work for a public land management agency where she can advocate for more Indigenous place-names.

“When we gave public presentations, tribal elders would come up to us and say how proud they were of the Native youth,” Tso says. “It meant a lot to see the positive impact we were having on them and the whole community. The work to change the name made me really happy inside.”