There is a pleasant tinkling of metals, frequently interspersed with soft-spoken Hopi conversation, as a small group of ex-servicemen moves about the classroom in the Hopi Indian High School at Oraibi, Arizona. The young Hopi veterans are the first enrollees in a silversmithing project organized under the G.I. Bill of Rights. Their instructor, Paul Saufkie, of the village of Shongopovi on Second Mesa, is an accomplished silversmith — an artist at fashioning the beautiful articles of silver and turquoise that are so greatly prized.

Silversmithing has never been an active art among the Hopi people, for both historic and economic reasons. Silver jewelry was introduced into the villages by the Spanish conquistadores shortly after their discoveries of the Rio Grande pueblos and the Hopi towns. The Spaniard was conqueror and enslaver, not the white Messiah that Hopi tradition prophesied would come to bring surcease to the tribe’s desperate struggle for survival. It was not until 1680 that sufficient strength was organized to drive out the invaders. The pueblos were reconquered after 12 years, but the Spaniards were never able to re-establish themselves in the Hopi villages. Nevertheless, during their ascendancy over the Hopi people, bribery through gifts of silver jewelry became so common that the wearing of these adornments was regarded as public admission of disloyalty to the village. It was not until about 1890 that prejudice had abated sufficiently for a few men to learn and practice the art of silversmithing.

The general scarcity of money among the Hopis has been a retarding influence in the development of silversmithing on any considerable scale. To accumulate stocks of sheet metal and wire, and of crude turquoise, requires a considerable capital investment. The necessary capital was not available to the individual Hopi. In some of the pueblos, notably Zuni, and in the large towns adjacent to the Navajo reservation,

silver and turquoise are provided by the large trading houses to whom the smith sells the finished product. No trading post on the Hopi reservation follows this practice.

For many years Dr. Harold S. Colton and his staff at the Museum of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff have devoted much of their energies and funds to projects for encouraging the revival of the old Hopi arts and crafts. This interest and help has resulted in the development of many fine artisans among Hopi men and women and the production of baskets, pottery and textiles of outstanding quality. Dr. Colton has long contended that Hopi traditional design is especially adaptable to the processes of silvercrafting. Thoroughly acquainted with the Hopi talent for fine craftsmanship, he has consistently urged the adoption of silversmithing — with the development of purely Hopi designs — as a part of the tribal culture.

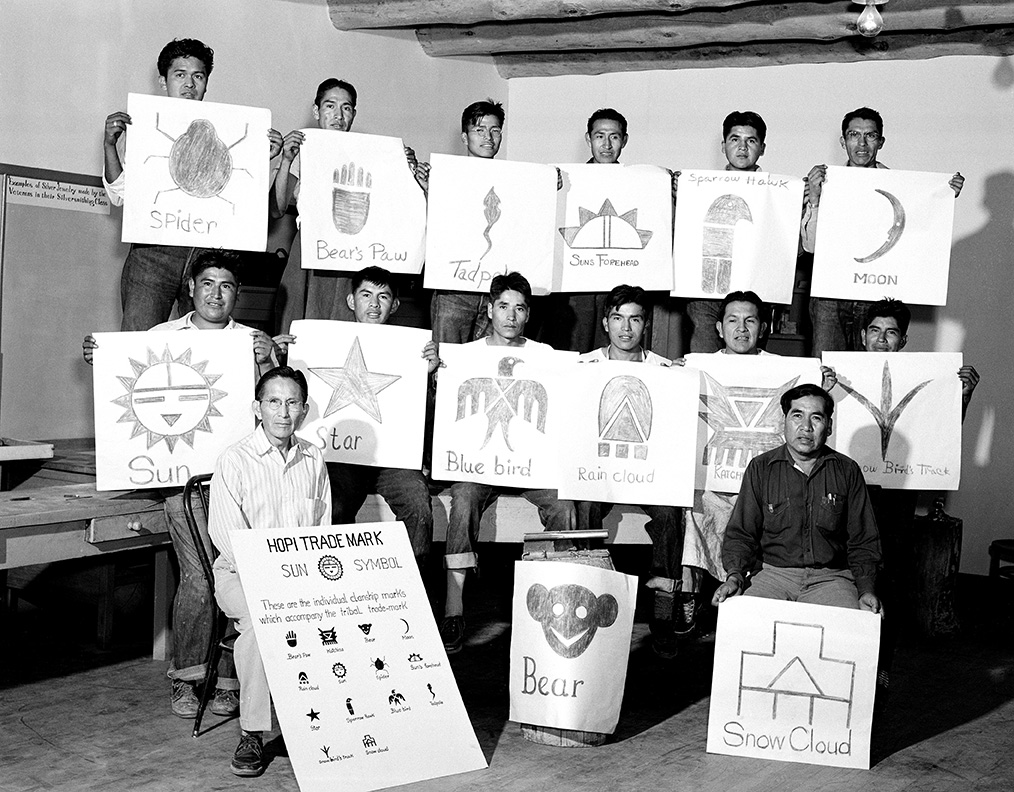

In the summer of 1946, Dr. Willard Beatty, director of education for the Indian Service, visited an exhibit of Hopi arts and crafts at Shongopovi. Here he conceived the idea of establishing a silvercraft school for Hopi veterans under the G.I. Bill of Rights. Fred Kabotie, a noted Hopi artist, agreed to act as director of design, along with his other duties as art instructor at Hopi High School. The project was further fortunate in securing the services of Paul Saufkie as head craftsman. It was Mr. Saufkie who had worked singlehandedly with Dr. Colton in rendering early Hopi designs in silver before the school was organized.

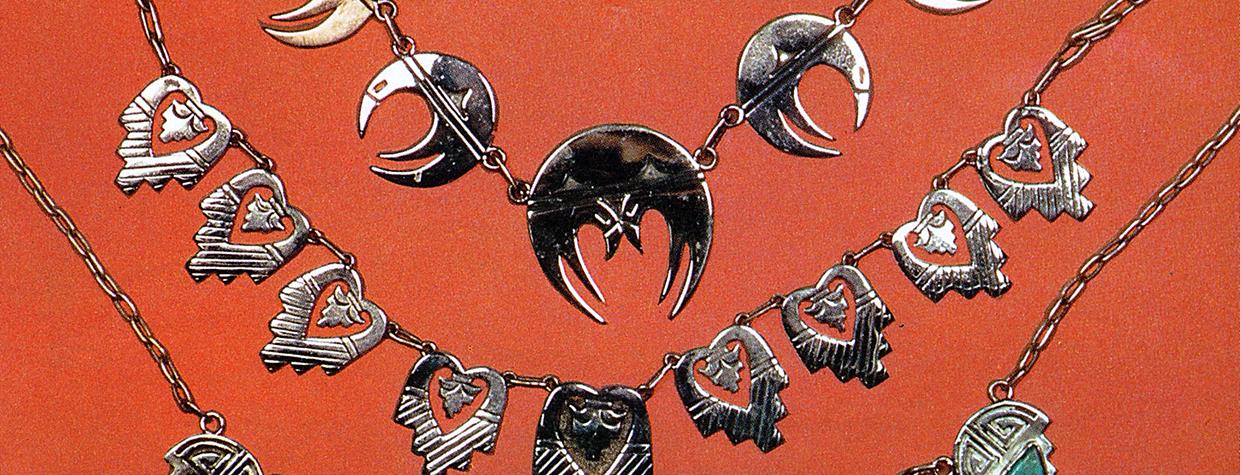

With the active encouragement and help of Burton A. Ladd, reservation superintendent, and Dow Carnal, reservation principal, the project was soon underway. In February 1947, 13 veterans had enrolled and were receiving daily instruction. Many beautiful designs were developed, some for die-stamping, others for the unique overlay technique, and still others for sand-casting. All designs were genuinely Hopi, stylized from the decorative patterns of old pottery and baskets. The intricate cutting, grinding and polishing was mastered by the eager students. Soon individual pieces were ready for exhibition at state fairs and annual ceremonials. An exceptionally high percentage of these won blue ribbons for excellence of design and craftsmanship.

Truly, something new and fine had been created. And just as truly, a way to artistic fulfillment as well as economic security had been provided for the students, whose class, now grown to 19, graduated on January 1, 1949. A group of 15 new students immediately moved into the classroom.

Shortly after the first class completed the prescribed training period, its members organized the Hopi Silvercraft Cooperative Guild. With the aid of the Indian Service, a loan was secured from the government to purchase materials needed for silver work. The Guild buys the raw materials from wholesale houses and the individual craftsman pays for these after his articles are sold. To further the interests of the Guild and the silvercraft class, the Indian Service purchased a Quonset hut and the members of the Guild, together with the class members, erected the building on the high school grounds under the supervision of the construction department of the Hopi Indian Agency. This building furnishes a room for the instruction of the classes and also provides a workshop, complete with electric power, for those members who find it difficult to work at home.

Indian jewelry may be loosely classified as of three general types: Navajo, Zuni or Pueblo, and now Hopi. In general, Navajo pieces are set with large stones and the silver is worked less elaborately than is characteristic of Zuni craftsmanship. Zuni bracelets, for example, are usually mounted with rows of very small stones or with groups of small stones set in clusters to form geometric patterns. Earrings are of intricate design, often set with many tiny stones and embellished with silver dangles, while Navajo earrings are generally single pieces of polished turquoise, without silver mountings, or strings of turquoise discs, worn with the string laced through the pierced earlobe. Hopi jewelry, employing turquoise as an accent rather than as the principal feature of the article, stresses design wrought in the silver.

Many of the finest examples of the silversmith’s art are seen only on the reservations or in the cases of museums and private collectors. Conchas of exquisite design and workmanship are made by many smiths but are seldom to be found in the curio stores along the highways. However, small replicas of these beautiful belt ornaments have become standard merchandise in most Western stores catering to travelers.

No story about Indian jewelry that fails to examine, at least briefly, the economic impacts of the craft and its products can be justified. Not only has the production and distribution of these articles of adornment become big business for some of the traders, but their existence has brought important changes in the economic structure of reservation life as well. During recent years the Indian Service has found it necessary to cut down the numbers of sheep, goats and horses that could be grazed on reservation land. Particularly among the Navajos, population has increased to a point where an economy on sheep can no longer sustain the people. This is true, in lesser degree, among the Pueblos and Hopis. The development of silversmithing as an extensively practiced craft and the introduction of the finished products into the channels of trade can be an important factor in relieving a situation that is rapidly approaching the status of a regional calamity. However limited the ranks of the smiths may be, the product of their talents constitutes new wealth to replace some of that lost through the breakdown of the agricultural economy.

Now, a word about buying Indian jewelry: Hopi Guild jewelry can always be distinguished from other Indian jewelry by the two trademarks that appear on its reverse. The mark common to all jewelry of the Guild is the Hopi Sun shield, backed by the Indian Arts and Crafts Board in Washington, D.C. Together with this, the mark of the clan of the individual silversmith is also to be found there.

Editor’s Note: Although the Hopi Silvercraft Cooperative Guild no longer exists, its traditions continue. In addition, the Indian Arts and Crafts Board continues to support American Indian artists by encouraging consumers to purchase authentic Indian art and craftwork. When doing so, it’s important to know the law and purchase only works produced by members of federally recognized tribes. Under the Indian Arts and Crafts Act, it is unlawful to offer or display for sale, or sell, any art or craft product in a manner that falsely suggests it is Indian produced, an Indian product, or the product of a particular Indian or Indian tribe or Indian arts and crafts organization. For a free brochure on the Indian Arts and Crafts Act, including how to file a complaint, please contact the Indian Arts and Crafts Board at doi.gov/iacb.