When Davina Two Bears was working on getting her bachelor’s degree at Dartmouth College in the late 1980s, she had such a hard time fitting in, and the courses were so difficult, that she almost dropped out.

“It was a lonely time,” she recalls. “I was a fish out of water.” Or, more precisely, Two Bears was a Navajo in New Hampshire.

Even though Dartmouth has had a mission of serving Native American students since its founding in 1769, the Ivy League school in Hanover, New Hampshire, is a long way from home for members of Southwestern tribes. Two Bears’ upbringing included time in the economically stressed, sparsely populated communities of Birdsprings (where she learned the Navajo language), Leupp and Tuba City, on the Navajo Nation. Her father was an alcoholic, and she was raised by her mother, who struggled to support the family. Meanwhile, most of Two Bears’ classmates at Dartmouth were white and came from polished urban environments on the East Coast. But Two Bears had received generous scholarships, and she knew getting a degree from Dartmouth would open up a world of opportunities.

“I didn’t want to be a quitter,” she recalls. “My mom taught me to finish what you start.”

Eventually, Two Bears transferred into Dartmouth’s anthropology program and found meaning in the study of Native American cultures, including her own. Her high school in Winslow, at the edge of tribal land, hadn’t taught Two Bears about Navajo culture or history, but the classes she took at Dartmouth finally did.

In 1990, Two Bears received her degree in anthropology from Dartmouth. She went on to earn a master’s in sociocultural anthropology from Northern Arizona University while working for the Navajo Nation’s Archaeology Department. Recently, Two Bears, 49, decided to go back to school to get her Ph.D. in archaeology and social context, with a minor in Native American and indigenous studies, from Indiana University.

“I research how the Navajo lived in the past,” Two Bears says. “It is very important for the Navajo people to have information, so we can tell our own story.”

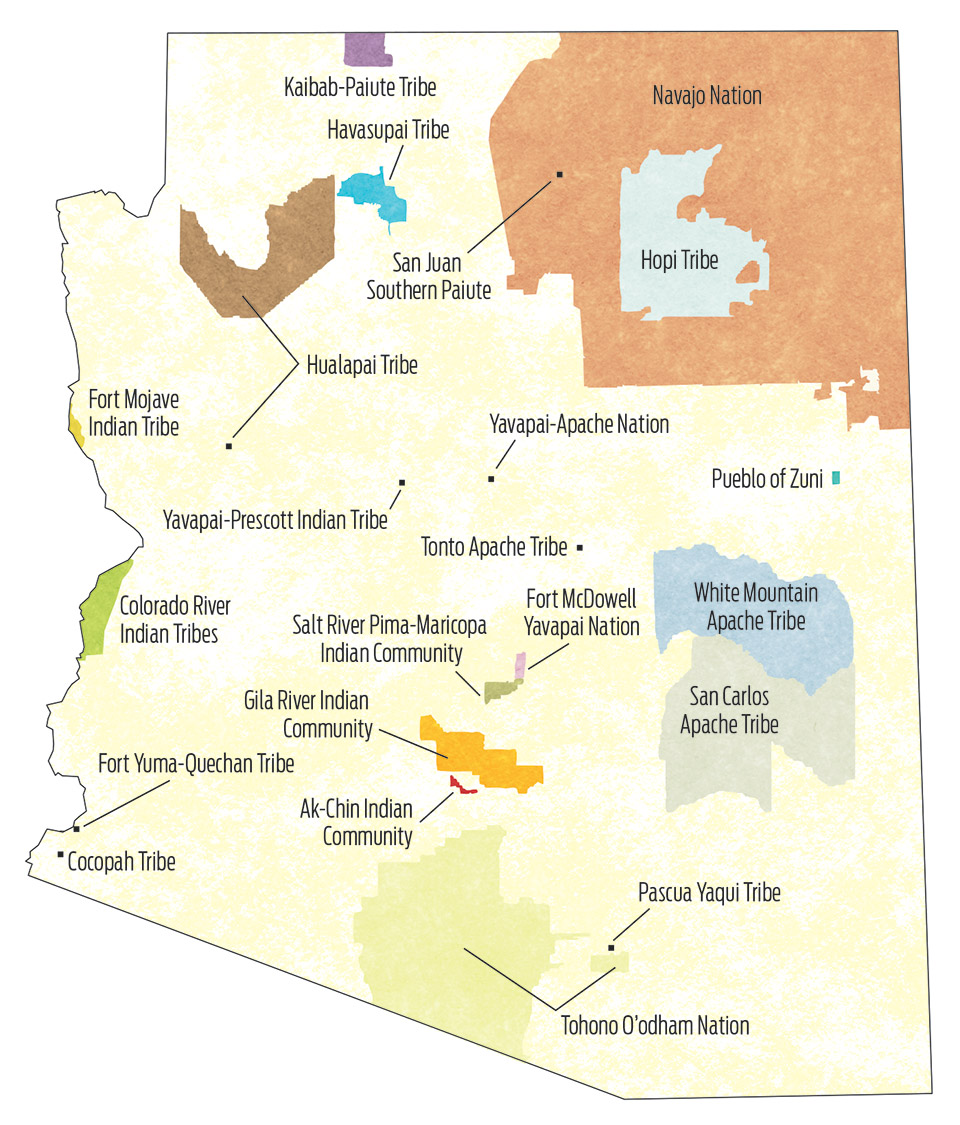

Between the Navajo Nation and the state’s 21 other federally recognized tribes, few other regions of the country can match Arizona’s wealth of indigenous history and culture. Arizona is home to the two largest Native American tribal lands in the United States: the Navajo Nation, in the Four Corners area of Arizona, Utah and New Mexico; and the Tohono O’odham Nation, along the U.S.-Mexico border southwest of Tucson. In all, about 28 percent of the state is tribal land. Too often, though, the culture and history of Arizona’s indigenous people has been interpreted through the filter of white “experts” — or not shared at all. But now, Native Americans such as Two Bears are out to change that. Whether by obtaining a graduate degree, running casino enterprises or promoting indigenous cultures on social media, many of Arizona’s Native people and tribes are flipping the script and using new strategies to determine their own future.

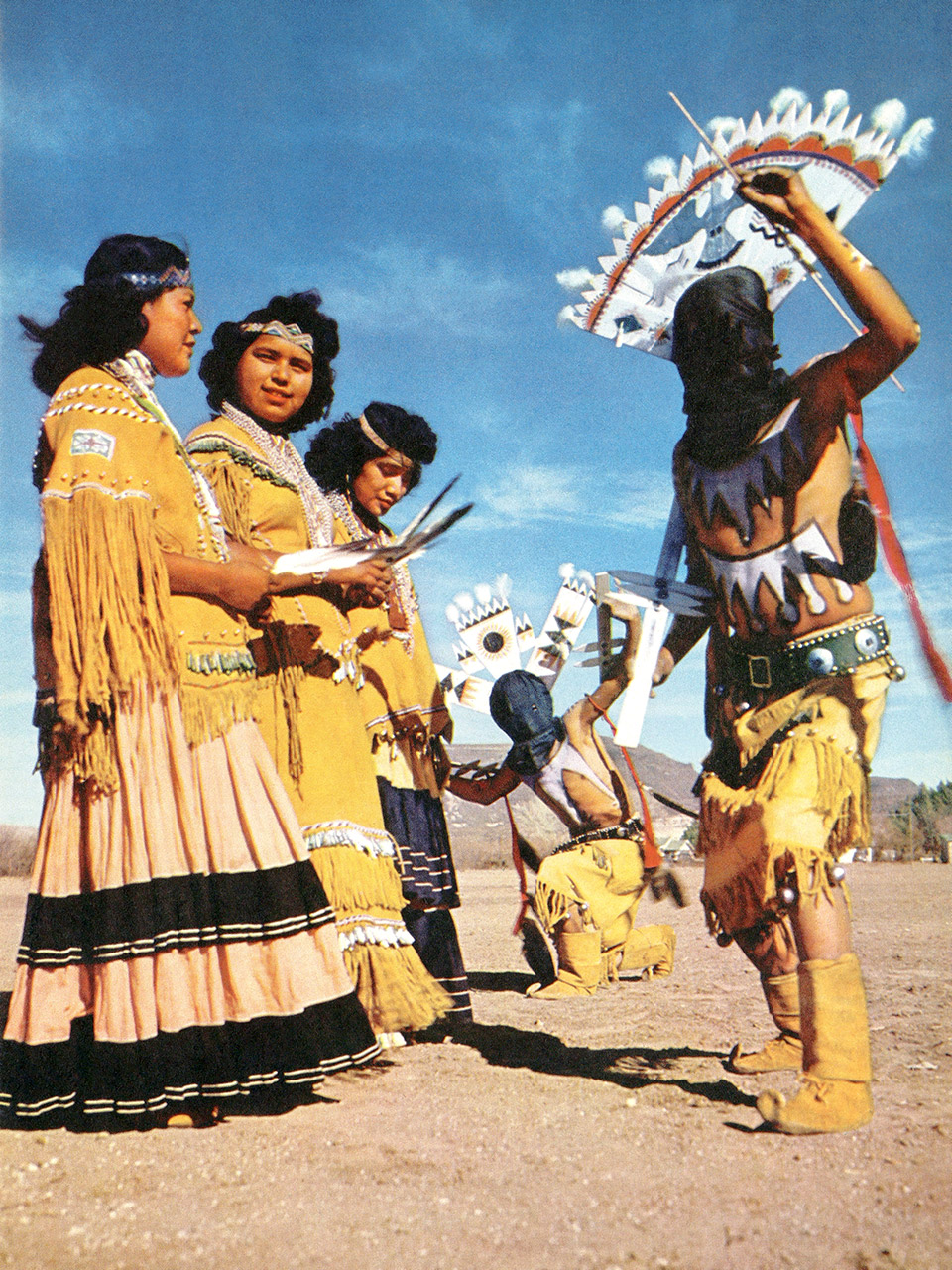

During pre-Columbian times, the indigenous people of the Southwest lived in every corner of what would become Arizona. For those Native Americans, the 17th century arrival of European colonizers launched a tragic series of events that led to epidemics, massacres, forced marches and brutal wars. When the dust settled three centuries later, perhaps the only upshot for Native Americans in Arizona was that, unlike tribes in the East and Midwest, indigenous people remained in their homelands — albeit on tribal lands much smaller than their traditional ranges. The 22 sovereign nations in Arizona have their own distinct dialects, mostly rooted in ancient Yuman, Piman and Athabaskan languages. While “tribe” is a word European immigrants came up with to describe those they were colonizing, the most common English translation for what each culture calls itself in its own language is simply “the people.” And the people view themselves as synonymous with their tribal lands, which are also their spiritual places of origin.

On the mesas and canyons of the Colorado Plateau are the Hopis, Zunis, Havasupais, Hualapais and Southern Paiutes. To the south are the Yavapais and Apaches, who roamed Central Arizona’s rugged upland country. In Sonoran Desert basins and the Gila and Colorado river valleys are people who thrived for thousands of years living on a landscape that received just a few inches of rain per year: the Tohono O’odhams, Pimas, Maricopas, Cocopahs, Quechans and Mojaves. While some sovereign nations, such as the Navajo Nation and the Kaibab-Paiute Tribe, are in the most remote areas of Arizona, others, such as the Pascua Yaqui Tribe and the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community, are rural islands surrounded by sprawling, paved-over Phoenix and Tucson.

Maurice Crandall is a member of the Yavapai-Apache Nation. He grew up in Albuquerque and in the Verde Valley, on land that was the traditional home of his ancestors but then was claimed by European farmers, ranchers and miners. Based in Camp Verde, the 2,400-member tribe is composed of two distinct cultures that the federal government combined when the tribe’s land was designated. According to Crandall, the Yuman-speaking Yavapais generally lived in Red Rock Country and west of the Verde River, while the Athabaskan-speaking Dilzhe’e Apaches roamed east of the Verde. Both cultures were semi-nomadic and relied heavily on hunting and on harvesting prickly pear fruit, piñon nuts, agave hearts and other desert plants. “They shared resources in the region and tried to get along before European immigrants arrived,” Crandall says. “We are now a distinctive bicultural tribe and have different ceremonies, songs and dances for each group.” Like many members of today’s Yavapai-Apache Nation, Crandall has family members from both cultures. But what sets Crandall apart is that he’s the first person in his tribe to earn a Ph.D.

After graduating from high school in Cottonwood in the mid-1990s, Crandall earned a bachelor’s degree in history from Brigham Young University, then completed master’s and doctorate degrees in history from the University of New Mexico. Crandall, 40, is now an assistant professor of Native American studies at Dartmouth.

Crandall has devoted extensive research to documenting the plight of his people. In the mid-19th century, during the Apache Wars, the U.S. military often wrongly assumed that the Yavapais were Apaches, and both groups were confined on the Rio Verde Indian Reserve, near present-day Cottonwood, in the early 1870s. In February 1875, the Army marched 1,500 Yavapais and Dilzhe’e Apaches 180 miles from the Verde Valley to San Carlos Apache Tribe land. Many starved to death or drowned in swollen rivers along the way. Twenty-five years later, when the people were allowed to migrate back to the Verde Valley, several hundred returned but found their land occupied by white settlers. “All their land had been taken, so they became squatters living in camps and working for wages at nearby mines,” Crandall says.

At the end of a decades-long process, the U.S. government established the tribe’s land in the 1930s. But by then, the federal boarding-school program was in full swing, and the tribe’s children were promptly removed from their homes. “All my grandparents, aunts and uncles were carted off to the school in Truxton Canyon, hundreds of miles away,” Crandall says. “They were beaten for speaking their language. It was very traumatizing.”

The fortunes of the Yavapai-Apache Nation and Arizona’s other tribes improved significantly starting in the mid-1990s, when the state began formalizing gaming compacts to allow casinos on tribal land. In 1995, the Yavapai-Apaches opened Cliff Castle Casino and Hotel. The enterprise has grown into one of the largest employers in the Verde Valley, currently providing more than 400 jobs. Revenue from the casino has been a “huge benefit” for the tribe, Crandall says. “It pays for our elderly programs, Montessori school, government offices and college scholarships,” he says. “The casino revenue is what put me through grad school.”

Of Arizona’s 22 tribes, 16 operate their own casinos, while the other six do not have casinos but can lease their slot-machine rights to other facilities. Those six include the Hopi Tribe, which in late 2017 became the last tribe to sign a gaming compact with the state. Combined revenue from all Indian gaming enterprises in Arizona totaled $1.81 billion in fiscal 2014, making gaming one of the most profitable industries in the state.

However, the thriving Central Arizona tourism industry, which draws patrons to Cliff Castle Casino, is a mixed bag for the Yavapai-Apaches. “The Red Rock Country of Sedona is our homeland, even though it is not part of the reservation,” Crandall says. “Boynton Canyon is sacred to us. But when we go to the site in Boynton to perform our ceremonies, we have to tiptoe through the golf course of Enchantment Resort.”

Many of Arizona’s Native Americans now live outside tribal lands. In 2012, the state’s 22 tribes had nearly 425,000 enrolled members, and of that total, just more than 240,000 were living on tribal lands. (Those numbers include residents of tribal lands that extend into other states, particularly the Utah and New Mexico portions of the Navajo Nation.)

The migration away from those lands is due in large part to a lack of economic opportunities, other than casinos. Additionally, a federal relocation policy, in place from the early 1950s to the late ’60s, encouraged Native Americans to move to cities. But Instagram and Facebook may be helping to reverse this trend. Carlos Valencia is one of a growing number of indigenous activists using the far-reaching power of social media to demonstrate that stereotypes about bleak tribal life and disappearing Native culture are wrong.

A member of the Pascua Yaqui Tribe, Valencia, 39, grew up in the community of Guadalupe, in the Phoenix metro area. Guadalupe is one of several Yaqui communities in Central and Southern Arizona, but the tribe’s federally designated land, roughly 1,800 acres, is just southwest of Tucson. The Yaquis in Arizona are the northernmost members of an ancient culture rooted in the Sonoran Desert and the modern-day state of Sonora in Mexico. Speaking in a dialect based in the Uto-Aztecan Cahitan languages, the Yaquis subsisted for thousands of years by farming along the Yaqui River — growing corn, beans and squash — and hunting large game, especially deer. After Mexico won independence from Spain in 1821, the new government began pressuring the Yaquis to turn over their valuable farmland. To escape persecution, and in some cases enslavement, by the Mexican government, thousands of Yaquis migrated into Arizona in the early 20th century. They established several communities in Arizona, but it wasn’t until 1978 that the tribe, which now numbers more than 21,000, gained federal recognition as an American Indian nation.

Valencia’s great-grandparents migrated to Guadalupe from Sonora and brought their Yaqui traditions and language with them. But Valencia’s mother, who grew up in the 1960s and ’70s, felt pressured to blend into the larger urban culture of Phoenix. “She raised me to respect being Yaqui, but she didn’t push me to embrace it,” Valencia says.

As a young man who married a Yaqui woman from Scottsdale, Valencia decided not only to embrace being Yaqui, but also to celebrate his heritage and encourage others to do the same. In 2011, he founded the Yaqui Pride Project, first launching a website and then adding Facebook and Instagram pages that now have thousands of followers. The project showcases traditional Yaqui culture, traditions and history for tribal members and the rest of the world. For nearly five years, Valencia has been traveling to the Sonoran community of Rio Yaqui, documenting his trips in photos and videos, and sharing them online.

“Technology is helping us share our language and traditions,” Valencia says. “Tribal members used to look down on being Yaqui, but now they are seeing the benefits.”

The virtual experience turned into a real one in June of this year, when Valencia organized a road trip to Sonora for people with an interest in Yaqui culture and history. “The experience blew our group away,” Valencia says. “The villages down there are very traditional. What we practice in the United States is a watered-down version of the rituals and cultural regalia from there.”

Valencia, who works for the tribe’s education department, is teaching himself the Yaqui language with help from friends in Rio Yaqui. He plans to make sure his children learn the language, too. “It is important that people find their way back home,” he says of his commitment to promoting Native culture. “I could work in New York City or LA and make more money. But for me, Guadalupe is always home, and living here as a Yaqui is a great source of pride.”

Navajo author and poet Laura Tohe grew up on the Navajo Nation during a far more oppressive period for Arizona’s Native Americans. “I attended boarding school during the era of assimilation, when we were forbidden to speak our language,” she recalls, noting that she had learned English as a second language from her parents and extended family. “I witnessed my classmates’ punishment for speaking the only language they knew,” she says. Just a generation earlier, her father and other Navajo soldiers were Code Talkers, using their language to save American lives and help win World War II.

Tohe’s grandmothers, mother and aunt were weavers and taught Tohe about tribal beliefs. “In the evenings, while my cousin and I carded wool from the recent shearing, [an elder] spun wool into skeins for her weavings and told us stories of Diné connections to the Earth,” she says.

Inspired by her female role models and a love of storytelling, Tohe became a writer, eventually earning her Ph.D. in English and becoming a creative writing professor at Arizona State University. In 2015, she was named the Navajo Nation’s poet laureate. Because Navajo is her first language, she sometimes thinks of poems in Navajo and translates them to English. Tohe says it’s critical that the Navajo language remain alive and spoken to sustain the unique values of Navajo culture, which revolves around connections to the Earth and each other.

“Shizaad bee hadínísht’é,” she says, noting an expression she uses: “I am dressed in the Navajo language.”

Even with revenue from casinos and newly enlightened government policies, tribal life in 21st century Arizona is no utopia. According to a joint 2013 report by ASU and the Inter Tribal Council of Arizona, the median life expectancy of Native Americans in the state is just 59. The premature-death rate among the state’s Natives is 76.5 percent higher than for the average Arizonan. Alcohol abuse and diabetes are among the leading causes of early mortality.

Tohe believes addressing current problems on Navajo and other tribal lands requires tending to previous generations’ wounds. “Boarding schools, dysfunctional families, colonization [and] violence are all historical traumas that need healing,” Tohe says. “The people need hope that there can be a better future and that they can be the resilient individuals their ancestors were.”

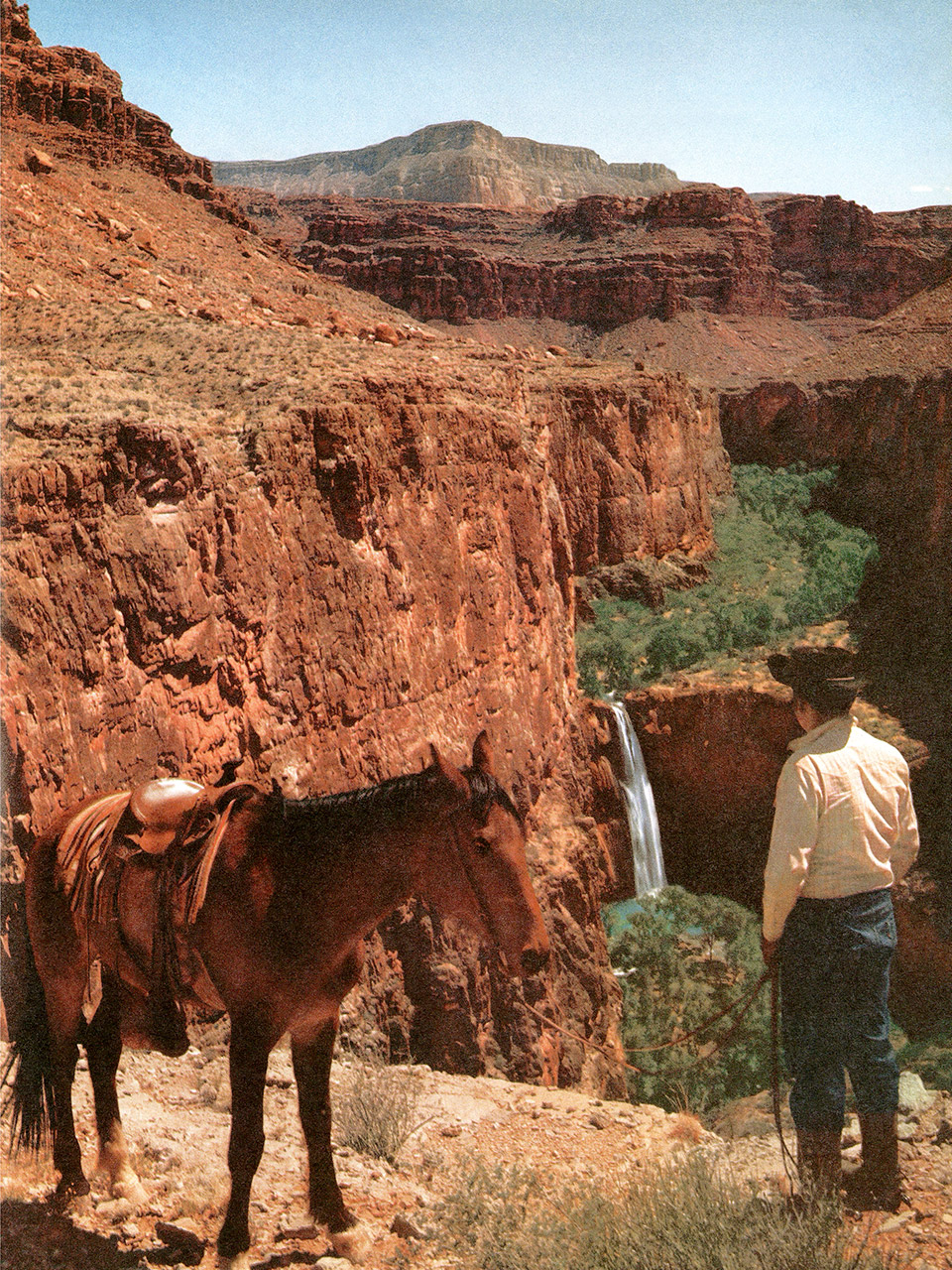

In addition to tribes’ internal challenges, there are constant external threats. Charley Bulletts is the cultural director for the roughly 360-member Kaibab-Paiute Tribe, one of the smallest tribes in Arizona, and his days are filled with fighting off assaults from all directions. One of 15 bands of Southern Paiutes, the Kaibab-Paiutes are descended from hunters and gatherers who have lived on lands north and west of the Grand Canyon. Many of the place names at the Canyon — including the Uinkaret Mountains, the Shivwits Plateau and the Kaiparowits Plateau — are based on Paiute words, and “Kaibab” is derived from “Kaivavitse,” which means “mountain lying down.” The tribe is based in Pipe Springs, and its land encompasses about 120,000 acres on the Canyon’s North Rim and the Kaibab Plateau.

“Standing Rock is happening here every day,” says Bulletts, comparing his tribe’s struggles to protests of the pipeline project on Sioux land in South Dakota. Many of the tribe’s sacred and ceremonial sites extend well beyond the arbitrary tribal boundaries and are frequently threatened by oil and gas development on surrounding Bureau of Land Management lands. But Bulletts takes the long view of environmental battles his tribe is facing — which is easy to do when you’ve lived in the same place for more than a thousand years.

“Southern Paiutes have been here since the beginning of time,” he says. “We still sing about when the lava flowed and talk about the mammoth. Our umbilical cord remains attached to Mother Earth, and our story will continue on.”

Davina Two Bears is making sure the stories of indigenous Arizona are not only told, but also researched in a way that honors Native values. For her Ph.D. in archaeology, she’s investigating Old Leupp Boarding School, on the Navajo Nation, and she’s returned to her alma mater, Dartmouth, as a Charles Eastman Fellow. After Two Bears completes her Ph.D., she plans to move back to the Southwest and teach at a university while continuing to do research.

“I want to go home. I miss my family and my tribe,” she says. But Two Bears knows she has a critical role to play in supporting Native students at Dartmouth who likely are homesick, too. “I tell them to go for their dreams,” she says. “I want to inspire them to get their degrees, but to not give up their cultural identity. It is very important to always hold on to that.”

For more on Arizona Highways' coverage of Arizona's Indigenous people, check out our newest book, Indigenous Arizona: The Portraits.