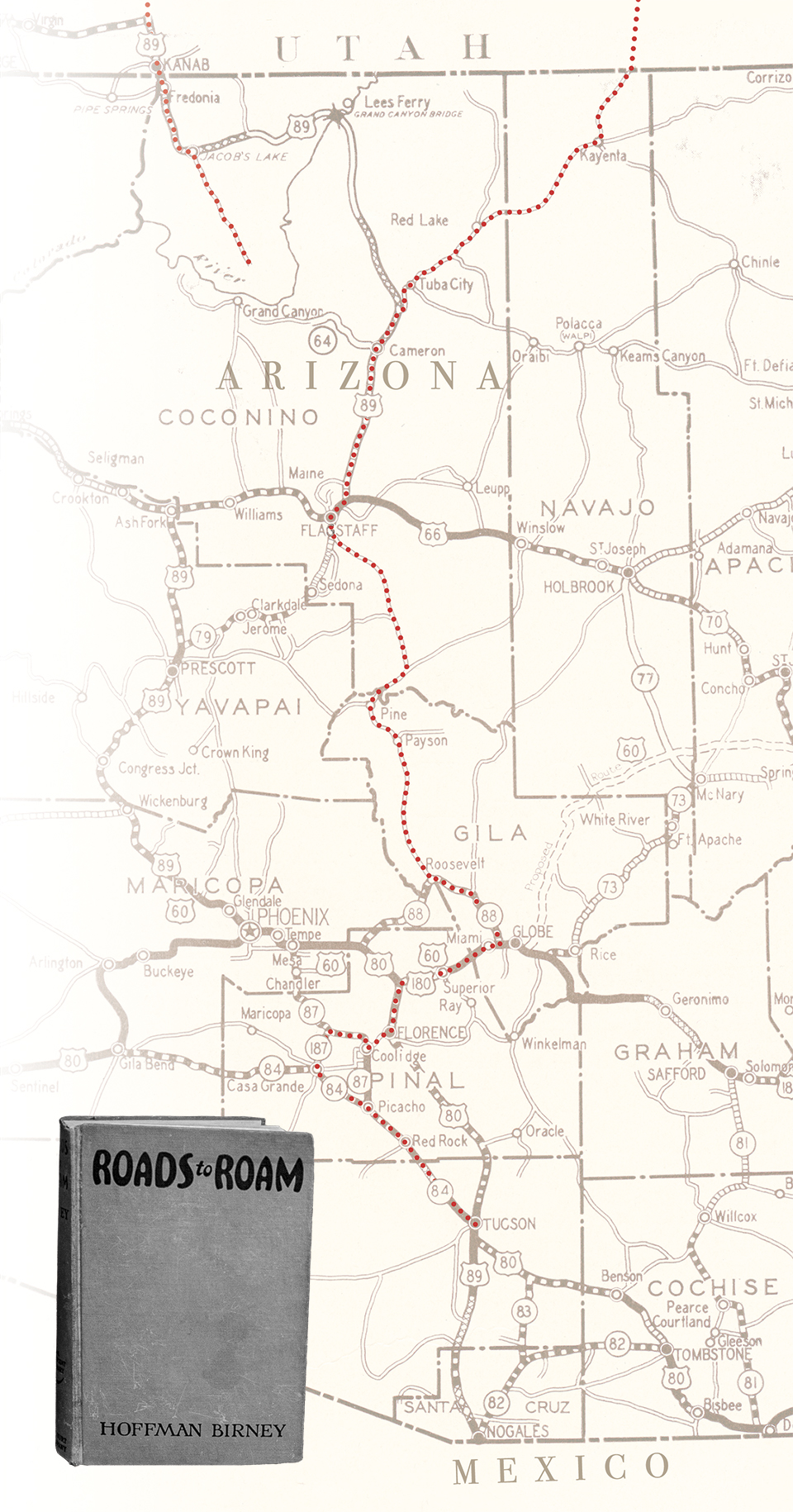

Upon haphazardly throwing a bedroll, thermos, shovel and revolver into a Chrysler roadster named Betsy, author Hoffman Birney set off on an early iteration of the great American road trip in 1928. From his home in Tucson, Birney drove north across Arizona as part of a 7,250-mile loop around the American West, covering the Four Corners, the Rocky Mountains, the Mojave Desert and California’s Eastern Sierra. Birney journaled throughout his drive and admitted, “I made no more preparation for the trip than I would to drive downtown.” He compiled his tales for his friends, with no intention of publication, but the resulting 1930 travelogue, Roads to Roam, became one of Birney’s most beloved books.

Admittedly, I have a historical crush on Birney. In photos, he appears timelessly cool, dressed in cutoff jean shorts, a wide-brimmed hat, aviator shades and rippling abs in lieu of a shirt. Like Birney, I’ve seen my life consumed in recent years by a long, strange, unplanned road trip. For three years, I roamed the Southwest in Sunny, my beater of a yellow Jeep Wrangler, and unintentionally wrote a book about it. When Sunny began her slow death in Monument Valley, I bought a truck and kept driving around the West with an orange hardcover copy of Birney’s book keeping me company in the passenger seat. When the delirium of long-distance driving takes over my imagination, I sometimes daydream about what traveling with handsome “Hoff” would be like.

My friends often caution me about dashing into whirlwind romances and adventures. But we all have our vices. What better way to get acquainted with Birney than on a long desert drive together? I turn down the radio so we can get to know each other, and we hit it off right away. It turns out, at the time of our road travels, we both are 36, write about the West and have a somewhat cautious wild streak. Birney denies this: “Adventure, romance, danger … all passed me by,” he writes. Yet his forays into Colorado River country included all of the above.

Even if Birney looks as if he could seamlessly step into the present, the landscapes, highways and towns he wrote about do not. At each junction between past and present, his witty and frank insights open my eyes to how much Arizona has changed in less than a century.

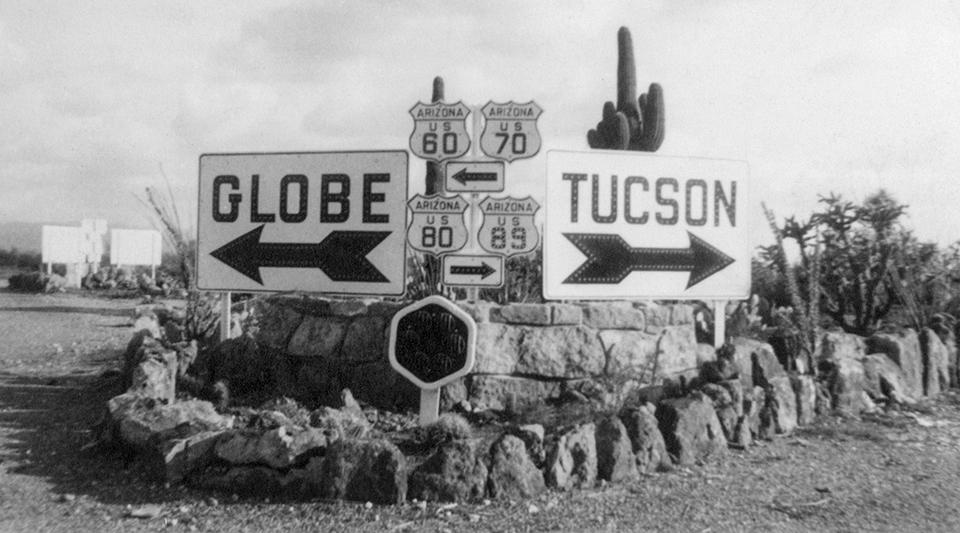

Heading north from Tucson on what now is Interstate 10, past the jagged pinnacles of Picacho Peak, I can’t be certain where Birney is leading me. Besides a brief stop at Casa Grande, he seems eager to get somewhere. When we reach the heart of the Central Arizona mining towns of Globe and Miami, I’m pleasantly surprised by his off-the-beaten-path sightseeing style: “Is there anywhere in the world such a thing as beauty in a mining town? Seemingly when man starts tearing her store of mineral from the earth, it reacts on his own soul and plays havoc with his aesthetic instincts.”

Turning away from the mines, Birney sings the praises of the Apache Trail, now State Route 88, and its sweeping views of the Salt River Valley. The road, through mountainous terrain dotted with saguaros, was constructed in the early 1900s so Theodore Roosevelt Dam could be built. The Phoenix we know today was, in a sense, born here. This catchment of the Salt River made the initial growth of Phoenix possible, and today, some 5 million people reside in the greater Phoenix area. Theodore Roosevelt Lake and other Salt River reservoirs now supply only a portion of the city’s water needs, with much of the rest being piped from the Colorado River via the Central Arizona Project.

Through the pines, our four wheels spin up to Flagstaff, where the pointed San Francisco Peaks loom over what Birney describes as a pretty little mountain town. Back then, Flagstaff, with a population under 4,000, already boasted a fusion of touristy stores and nearby wilderness. “Within what one might call the metropolitan area of Flagstaff are … the prehistoric ruins at Elden and Wupatki; and Sunset Mountain,” he writes. “Flagstaff is on the National Old Trails Highway and is, along with Williams, the principal port of entry to Grand Cañon.” Birney also mentions ice caves on O’Leary Peak, which is near present-day Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument. I fill Birney in about climate change as we sit in traffic on Historic Route 66, which was brand new during his road trip. I hassle with parking to pick up gourmet coffee and breakfast burritos to go; then, we continue north.

Roadside billboards taunt Birney with “Where will YOU spend Eternity?” and “Repent now” as we drive away from Flagstaff, across the Little Colorado River at Cameron and west toward the Grand Canyon. Upon arrival, Birney blurts, “Well, there’s the Big Ditch!” For a literary guy, Birney puts me off a bit with his first impression. But eventually, Birney’s trip to the Canyon takes him as close to a religious experience as a self-proclaimed atheist can get. He later writes that “over the Grand Cañon broods a hush that is beyond human conception,” and he proceeds to fulfill his “mad desire to see the [Colorado] River,” which then was a free-flowing, muddy maelstrom.

Yet plans were already being formed to construct Boulder (now Hoover) Dam downstream to form Lake Mead. Birney has a bad feeling about that. “The Colorado River is a distinct personality,” he writes. “She will probably submit very passively to the process. … Then will come the awakening. The sullen red river will brood in her fetters for a hundred years — a century is nothing to her — but then one day she will realize that she is bound.”

He adds, “Maybe they can get away with it, but I know I’ll never choose to live anywhere below that barrier.”

Less than a century later, Lake Mead’s water level is at an all-time low, putting water and hydroelectricity for millions of Americans at risk.

As a champion of wild rivers, Birney speaks my love language. With the future of Lake Mead’s water levels in question, the prospect of decommissioning Glen Canyon Dam upstream is gaining momentum. This would prop up water in Mead while allowing the Colorado River to retain some of its natural identity in both Glen Canyon and the Grand Canyon. It’s the opposite outcome to Birney’s prediction, but he’s not wrong: The river is showing the dramatic ebb of her personality.

East of the Canyon, we enter Navajo and Hopi lands. I stare out the window as we whiz past families riding horses and herding sheep. “Here lies the true Painted Desert,” Birney sings at first. “The use of the term to describe any other terrain in the Southwest is not justified.” Later, though, he gripes about the roads to Tuba City: “Somewhere in America there may be — I say there may be — three hundred miles of road worse … but I doubt it, and I know I would not wish to drive it.” I’m starting to notice his mood swings.

"Roads to Roam" was just one of dozens of books Birney wrote. He was also well known as a New York Times book critic. Often, he published his work under the pseudonym David Kent. | MORGAN SJOGREN

The modernized U.S. Route 160 ushers road warriors through pastel badlands toward Tuba City and the distant Four Corners. Farther north, on U.S. Route 163, it’s common for hordes of tourists standing in the middle of the road to take photos of the burnt red pinnacles of the Monument Valley skyline for Instagram. Birney liked to giggle at tourists, too, despite admitting that he was one of them. Eventually, folks do set their cameras down, scattering to the tumbleweed-lined shoulders, when the 18-wheelers come screeching by. These routes were paved in the mid-20th century to make way for coal and uranium mining. I can’t help but wonder: Would Birney have resisted the notion of an improved road if he understood it would open the doors to industrial development and mass tourism?

Despite the popularity of Roads to Roam, the book does little to showcase Birney’s literary career as a New York Times book critic and author of 30 novels. He even lent his literary skills to the U.S. Army, as a deputy chief of reports and publications on ballistics. And he hinted at a desire for anonymity by writing under the pseudonym David Kent.

Perhaps the latter is why public information about Birney’s personal life is scant. He was born in Philadelphia in 1891, attended Dickinson College and served in the Army during World War I. Despite his claim in Roads to Roam that he had a “bilious and cynical eye upon romance,” he married Marguerite Agnes Bovington in 1930 and had one child with her.

Knowing so little about Birney’s history makes it easier to sit in his roadster and take his idiosyncrasies in stride. A handsome face can’t obscure red flags: His rantings oscillate between defending Indigenous peoples against the federal government and using culturally offensive language to describe them. While talking that way may have been common during Birney’s era and earlier, that reality doesn’t justify racism.

By keeping my personal intimacy with Birney distant, I observe the desert landscape through his gaze without imprinting personal judgments. I’ve found that listening, while humbling, often teaches me more than arguing, which rarely ever changes anyone’s mind. As our drive stretches on, it seems apparent that ours might be a short-lived romance, past or present.

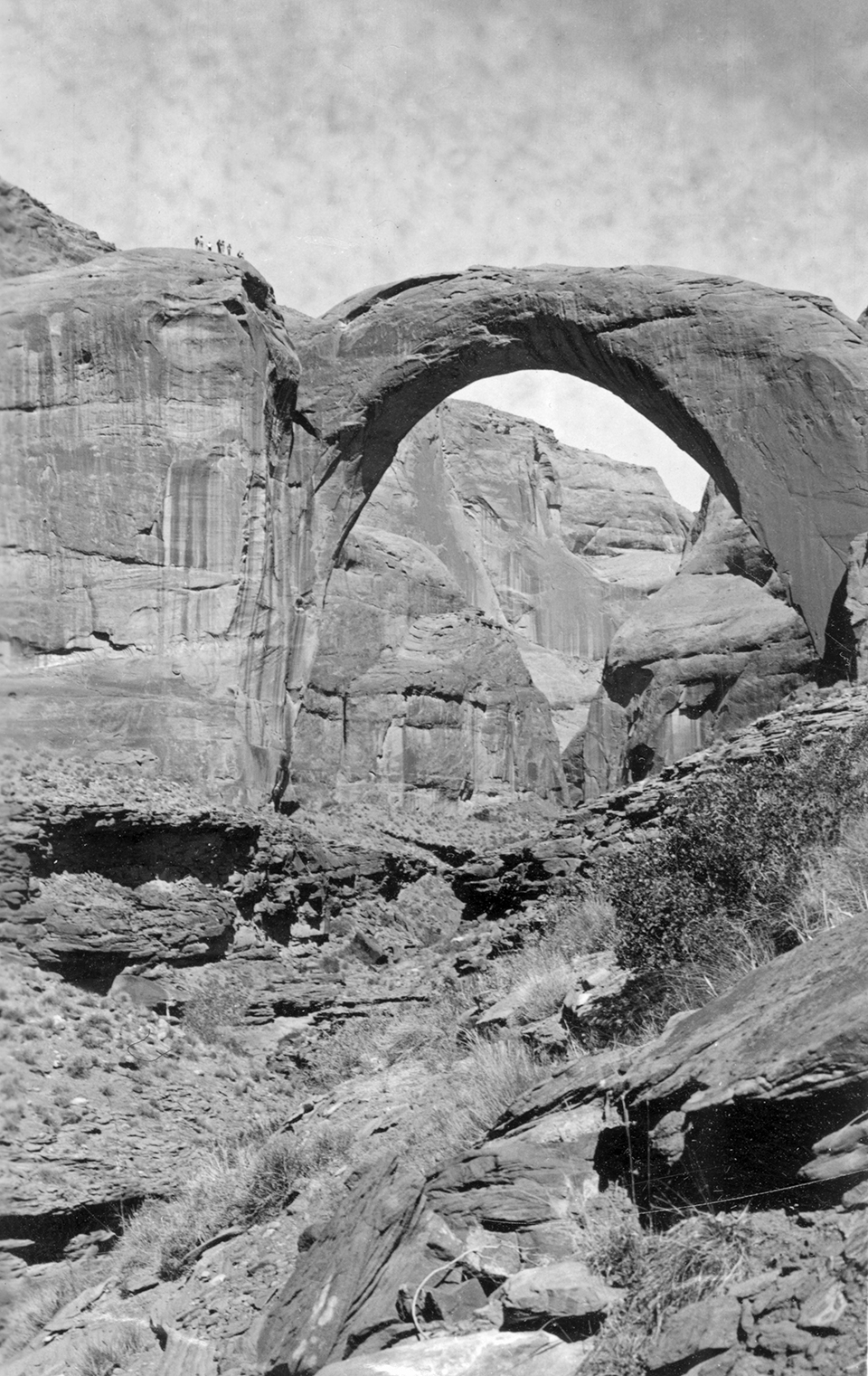

After his forays beyond Arizona, Birney returns to the Southwest, by way of Utah — or “Mormon Land,” as he calls the distinctly American religion that so fascinated him, he started writing about it. Back along the Arizona-Utah state line, at Navajo Mountain, Birney ditches Betsy and hops on a pack mule. Guided by a Paiute man named Hotshot, he rides to the fabled Rainbow Bridge, where his reaction to the 275-foot-wide sandstone arc is lackluster. This is a formation that authors, myself included, are often unable to adequately describe in words. But taking the backcountry route, as opposed to a boat on Lake Powell, is still a spectacular and challenging way to walk through the history of the Glen Canyon region. (Additionally, boat tourism to the bridge has been severely affected by Lake Powell’s lower water levels.)

Birney eventually admits that Rainbow Bridge’s location, in some of the most remote and lonely country in America, makes it a gem. I don’t see eye to eye with Birney’s nonchalance about such spectacular geology. Then, it rains. Birney whines and curses, and I find myself wondering how much longer it will be until this East Coast city slicker will run from the desert back to his home. It’s not the first date on which I’ve experienced this, and I’m sure he has other work to do.

Hotshot. | NORTHERN ARIZONA UNIVERSITY CLINE LIBRARY

Near the end of the trip, inspired by the Ancestral Puebloan dwellings he encountered in the Four Corners area, Birney pauses to reflect. “Twenty-three years before, I had stood in almost this precise spot,” he writes. “It seemed that centuries, eons, had elapsed since that day in the fall of 1905. I’d wandered far. I’d lost, and I’d gained. I’d known adventure, adversity and some measure of success … but here I was again.”

Birney’s century-old musings about the changes in the Southwest are a prophecy foreshadowing the Arizona we know today, as well as a snapshot of what remains intact. Where open roads have helped wanderlusters such as me and Birney roam, they also eased the access for activities that do harm to our planet.

I’ve enjoyed my travels with Birney, and I do recommend his book to Southwest history buffs, road-trippers and bookworms. But his outlook — “Hell, why struggle with philosophies? It’ll all be the same in a hundred years” — is too apathetic for me. As someone who perpetually wonders what the next century will hold, not only for humans but also for the wildlife affected by our developments, I want to believe we can choose a better path and help nature recover from our missteps.

As we drive across Glen Canyon Dam, Birney and I agree to part ways. I let him out on the other side of the bridge. Perhaps he can refine his philosophy there.