Editor’s Note: The celebration of our 100th anniversary continues with another wonderful piece from another wonderful writer. This month, it’s Ross Santee. “Ross thought like he drew, in black and white,” said Jo Baeza, a dear friend to Mr. Santee and a longtime contributor to this magazine. “A man was a friend or an enemy. His West was a battleground between good and evil. He slept with a loaded Colt .45 six-shooter under his pillow.” Mr. Santee first appeared in Arizona Highways in August 1936, when we published a review of one of his books. He wrote many, including Lost Pony Tracks, which we excerpted in June 1950. In April of this year, Mr. Santee joined 14 others in the inaugural class of the Arizona Highways Hall of Fame.

IT WASN'T A PONY that finally set my friend afoot after 50 years in the saddle. He was working as a stockman on the San Carlos Reservation when he began to have dizzy spells. While always generous with his family and friends, the old waddy’s own troubles were something he kept to himself. It was when he awoke one morning to find himself blind in one eye that he rode in to see the doctor. High blood pressure had caused it all. Since the other eye was affected, too, he was retired on a small pension. Fifty years in the saddle is a long time on a horse. Only one who has ridden the range knows what it means for an old cowboy to be set afoot.

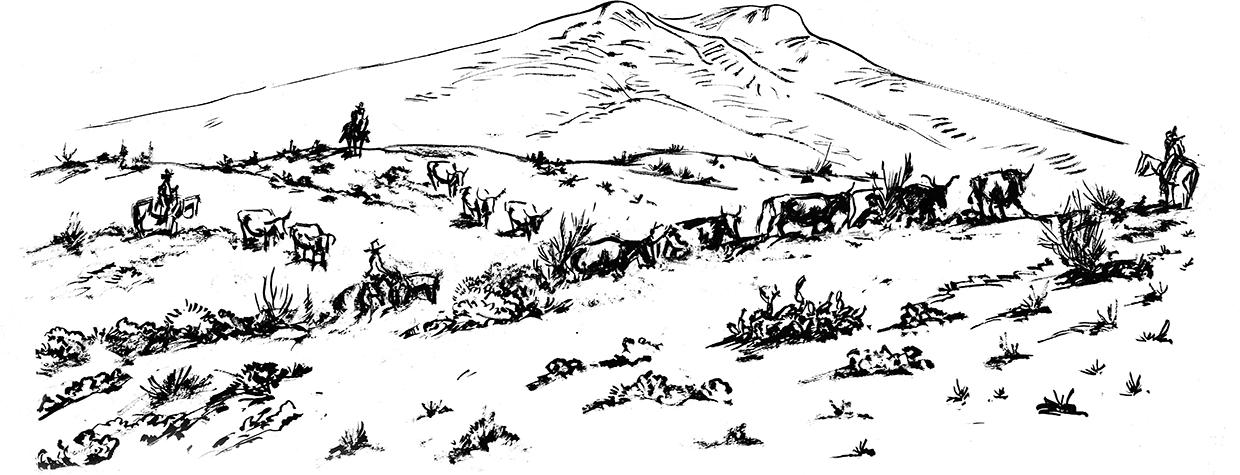

The Bar F Bar and Cross S outfits were shipping at Cutter. It was back in the early teens. The Bar F Bar outfit had brought down 800 head, mostly gentle stuff — some of them too gentle, I thought, for I was driving drags. Coburn Bros., who owned the Cross S at that time, were shipping 2,900 head, mostly old Mexicos, and they were as wild as black-tailed bucks. They spooked at every strange sound and smell; at times, they ran for fun. While the two herds were held some distance apart, the Bar F Bar herd caught the spirit of the thing. Sore-footed drags that could hardly untrack themselves on the drive to the pens rolled their tails and went hog wild.

There was the click of the hooves, the rattle of hocks, the rumble of the herd. You could feel the ground tremble when the cattle went into a run, and you could feel the pony’s heart you rode pounding against your knee. It was after a run that a rider rode out of the dust and flashed a smile my way.

Strange, how some little things stay in the back of one’s head after all the years. The horse he rode, a bay branded with a figure-2 on the jaw, was caked with dust and sweat. The rider was caked with it, too. When he pulled his hat, I took him for an Apache, his hair was so black and coarse. But I knew I had him pegged wrong when I noticed his eyes; they didn’t track with his hair. His eyes were blue and friendly, yet they made me think of the ice on a tank in winter. He swung down, loosened the cinch, straightened his saddle blankets. I’ve forgotten his passing remark. But I remember the smile he flashed before he rode back into the dust.

“Who’s the little wart?” I asked a waddy who rode beside me.

“Shorty Caraway,” he said. “One of Coburn’s top hands.”

Later, I jingled horses for him when he was foreman on the Cross S. In bad weather, we slept in the same teepee. Always tolerant of other men’s weakness, Shorty asked no odds for himself. He could “smell” trouble coming, and he could usually head it off. For the cowboy, always an individualist, is often a prima donna, too. Things are always brought into sharp focus on the range; cowboys in camp together often get on each other’s nerves.

Shorty knew all the symptoms when a waddy was about to “bow up an’ quit.” He would take the waddy aside. “Mind doin’ a chore for me? Will you take a note for so-an’-so in town? Can’t get away myself. An’ say, when yo’re in town, have some fun for me! We’re movin’ to Alkalai; pick us up there in four days.” I’ve never seen a cowboy fail to return. After he’d kicked the lid off in town, he was glad to get back, too. There was never the big fight, the big quitting, when Shorty ran the spread. He knew horses, wild cattle and, above all, he knew men.

There were two punchers in the outfit who didn’t speak. If by chance they met at the coffee pot, you could fairly see their hackles raise. Shorty put them in line camp together. Since both waddies were gun-toters, we looked for a killing. “There won’t be any trouble,” Shorty said. “They’re just like a couple of kids — one’s afraid to pull his gun, an’ the other knows he dassent.”

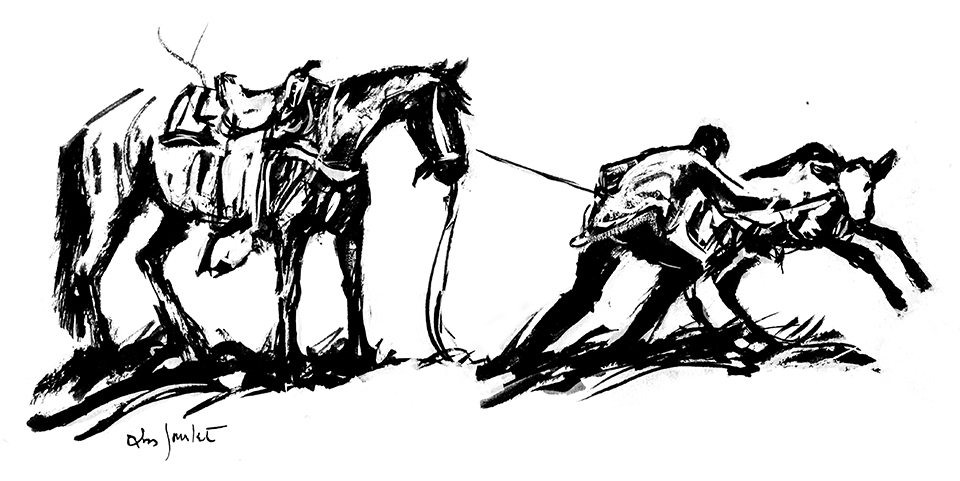

As foreman, Shorty never took the best of anything for himself. He took his turn at flanking calves, and in the corral, the roping was always divided among the men. Nor did he take the best horses for his string, as is a foreman’s right. There were several old ponies in his mount, long past their prime, that Shorty had a sentimental attachment for, yet he caught more wild cattle riding on them than some cowboys riding tops. There was Wine Glass Bucky, a pony Shorty had broken years before. Bucky often stumbled now in a race after a wild steer. Afraid some young puncher might abuse him, Shorty kept the pony in his string.

Shorty was camped alone when Wine Glass Bucky crossed over to the place where all good cow ponies go. “I should’ve knowed,” said Shorty, “knowed there was somethin’ wrong. Bucky was always gentle as a dog, but this night he woke me up a-pawin’ at my bed. I run him out of camp. He woke me up the second time a-pawin’ at my bed. I run him off again.” When Shorty told me, there was a mist in his honest blue eyes. “Bucky didn’t go to his own kind, or go off alone — he come to me. An’ I let the ol’ boy down. When I turned out next mornin’ with the mornin’ star, ol’ Bucky was a-layin’ dead just outside my camp.”

MOST COWBOYS ARE GOOD storytellers, and they like their stories tall. We all sat back expectantly when Shorty took over at night around the fire. He had a way of weaving fact into fiction — he made fiction sound like fact, and always there was humor that bubbled as from a spring. One night in camp, the conversation turned to rattlesnakes, and why it was so easy to shoot a snake’s head off with a pistol. One faction claimed the snake struck at the bullet. We argued pro and con.

“Ever see one swim?” said Shorty. None of us had had that pleasure. “I seen one swim across the river. It was down at Horseshoe Bend. He held his head an’ tail out of the water, just seemed to slide right through it. I’d never seen one swim before, so I follered him across. But when I tried to get him to take to the water again, ol’ snake got on the prod. I finally got tired a-messin’ ’round with him; I got a pole an’ was about to knock him in the head. Reckon he figgered what was on my mind, for he took to the river again, but he only swum halfway across an’ then he coiled. Last I seen of him, he was floatin’ downstream, still coiled, a-spittin’ at me over first one shoulder an’ then the other.”

There was always a twist to things, the way he told a story. Bob Robinson, one of the owner’s sons, spent a summer with the outfit. Bob was 12 at the time, and with no one to insist he wash behind his ears, Bob really took himself a three-months holiday as far as washing was concerned. The outfit was camped at the Spur camp the night his parents came to take him into school. “He was a good cowboy,” said Shorty, speaking to young Bob’s mother, “never bellyached anytime when things got a little tough. An’ among other things, he’s learned to make Dutch oven bread — an’ ya know, Mrs. Robinson, he even got so he washed his hands sometimes before he made it, too.”

Aside from his feeling for horses, Shorty had a weakness for stray boys, for boys still ran away to become cowboys at this late date and time. Shorty could spot a runaway at a glance in town. If the boy wanted to tough it out and be a cowboy, sure enough, Shorty would help him get a job. If the boy was homesick and wanted to go home ... well, Shorty could fix that, too. The fact he was often taken advantage of never bothered Shorty. He’d been a stray himself.

He was 14 when he ran away from the little farm in East Texas. It wasn’t that he wasn’t treated well, but to be a cowboy was the only thing that was ever on his mind. His father followed and brought him home. But a year later, his father, thinking it only the passing fancy of a boy, bought him a pony and saddle, gave him $40 to go with the $2 Shorty held, gave his son his blessing, and the boy was on his own. When Shorty returned on his first visit, it was quite a homecoming; not even his mother knew him, since he’d been gone for 20 years.

It wasn’t as simple as he thought the first morning he rode away. He was welcome at any ranch, yet he couldn’t land a job. And the pony had all the best of it when Shorty missed a ranch he was headed for: While Shorty took up another notch in his belt, the pony filled up on grass. Shorty had no bedding except his saddle blankets. Nights on the plains are cold, and he was usually up and walking long before the morning star appeared — walking to keep warm. Yet not once did it occur to him to go back home. In the great sweeps of country that stretch away as far as the eye can see, he had found the thing he wanted.

He rode the chuck line for six months. He was wearing castoff clothes cowboys had given him, dressed like a little range bum — considerably ganted, too — when he finally caught on as a chore boy with an outfit in New Mexico at $15 a month. It was a straight horse outfit where they broke horses the year ’round. Shorty stayed two years. There was hardly a day he wasn’t on a pitching horse. When he rode into Arizona to try his wings, there was no horse he feared or one he could not gentle.

IN ARIZONA, HE BROKE horses and punched cows. He never made the big circle from Canada to Old Mexico, like so many of his kind; most of his riding was done in Arizona. Shorty liked a country where the climate fit his clothes. The Chiricahuas, the Flying H’s, the C.K.’s, the Wine Glass outfit ... all knew his pony’s tracks. Shorty knew the Tonto, Black River, the Gila and the Salt, when whitewater ran over his saddle. Two weeks in town on the Fourth of July, two more at Christmas. The big money in the rodeos came after Shorty’s time, but he always won his share of money whenever he hit town. Good roper, good bronc rider, all-round top hand. And he never missed a chance to have a little fun.

Time to be serious, too, when a cowboy was trying to get ahead. He and a waddy bought a little bunch of cattle, got them on good terms. While Shorty coyoted and nursed the dogies, his pardner was to work for one of the big outfits and keep the bean pot going. Shorty didn’t know he was out of the cow business until a man rode to his camp one evening and showed him a bill of sale. His pardner had sold him out. “A good deal, too,” said Shorty. He laughed when he told me about it. “There was only one thing about the deal I didn’t like. My pardner got drunk an’ spent the money — I never got a cent.”

He went back to breaking horses and punching cows. Then, a wealthy cowman cut him in as a pardner. Shorty was to pay his share of the cattle out in wages. Once again, he lived alone and nursed the dogies. The years slipped by. He had his share about paid out when his pardner insisted they take on more cattle and more obligations at the bank. It was during the lush years in Arizona when the rains came when they were needed; every range was green, and all were overstocked. Then came the drop in prices, and the drought that broke so many cowmen. When they turned their outfit over to their creditors, Shorty’s worldly goods consisted of a war bag, full of dirty clothes, and Puzzle, a pet horse. Not much of a showing for almost 20 years’ hard work. It was known his pardner got the best of it, since he landed on his feet. But any feeling Shorty had, he kept strictly to himself. Never have I heard him speak of any man unless the word was good. He went back to working for wages again. He was foreman now for some of the biggest spreads.

In the middle ’20s, he went over to the coast just to have a look around. With a couple thousand in his Levi’s pockets, any cowboy can have fun. But when he located a married sister, Shorty found her very ill — an operation was necessary. Day and night nurses melted Shorty’s roll. To complicate matters further, there were two small children, a baby boy a few months old and his brother not yet 4. So, Shorty, to supplement his dwindling roll, rode in Western pictures at $10 a day. They paid more if a man did stunts and doubled for the leading man. And while that worthy stood by in all his finery, with a six-gun on each hip, Shorty rode pitching horses for the hero, swam rivers and rode horses over cliffs.

“I’d seen him in the movies lots of times,” said Shorty, “an’ admired this hombre’s nerve. He was just about as sweet as anyone I’d ever seen on a horse, an’ come to find out he’s just a ‘ham’ that couldn’t even ride in a wagon. At first, I wondered how he could look a real cowboy in the eye. But there’s another angle. If this ‘ham’ was hurt, it would hold the picture up, while cowboys, who risk their necks an’ do his stunts, are always a dime a dozen.

“Ever wrangle any kids?” I shook my head. “I never did either, till I took my sister home to Texas. She was in a berth, not able to sit up. Me an’ the baby an’ the 4-year-old had the seat across from her. A nurse had showed me how to fix the baby’s bottle, but she forgot to tell me how to change his diapers. Our outfit hadn’t been loaded long until the baby started bellerin’. I didn’t have to look him over, either, to know he’s messed himself. From the way some people looked at me, it wouldn’t a-surprised me none if they called the conductor an’ throwed our outfit off. But I waited till the train stopped. I grabbed a newspaper then an’ carried the baby off the car. I laid him on the ground, an’ after I’d cut the clothes off him an’ throwed ’em away, I wrapped him in a paper. But it seems a nice white-haired lady was watchin’ from the window. Mebbe she figured I was about to cut his throat when she saw me pull my knife, an’ she met me when I mounted again. ‘Let me take him,’ she says. She drug out clean clothes from the baby’s war bag and took him into the ladies’ room. When she brought him back to me, the baby was laughin’ again an’ smellin’ like a rose.”

Shorty was in his late 40s when he married. Aside from his mother’s red hair, Allen Jr., squatted on his little boot heels beside his father, was Shorty all over again. And often — to the consternation of his mother — Allen talked like his father, for the relation between father and son was always that of one cowboy to another.

WHEN THE GREAT APACHE Reservation was given back to the Apaches and the big outfits, the white outfits, were forced to move off, Shorty went to work for the U.S. Forest Service, counting cattle for the government. Most cowboys are hurt at times. Shorty was 50, and he’d already had his share of broken bones. While he was working for the Forest Service, Shorty had his biggest wreck when a horse pitched off a hill with him. When he was found, it took six hours to get him to the hospital in town, where they discovered eight ribs were broken and his lung had been punctured in two places when the pony fell and rolled over him. Shorty had had double pneumonia twice before this wreck, so it was touch and go with him for a time. But the old cowboy licked it, and at 60, he could still ride a pitching horse when a pony broke in two.

Shorty had worked with Apache cowboys ever since he came to Arizona. Unlike so many of his kind, Shorty had never taken advantage of them, always treated them as equals. And the Apaches still respect an honest man with courage. It was the Apaches who petitioned the agent that Shorty Caraway be appointed a stockman on their reservation. An old Apache, a mutual friend, spoke to me when Shorty was retired. “Not good,” he said, “not good for us when Shorty goes. Shorty always friend.”

In the good old days, there were several things an old cowboy might do when he was set afoot. He could work in a livery stable, tend bar or act as a peace officer. Now the livery stable has gone, and tending bar has become a complicated thing. No longer does the barkeep’s job consist of keeping order with the house gun, serving beer in bottles, and liquor taken “neat.” But Shorty wasn’t idle long. He got a job as a guard at the penitentiary, where he was among old cowboy friends. There were old friends among the inmates, too, old cowboys who were making quirts and hackamores, who had been set afoot by the law.

We haven’t seen each other in some time, but we keep in touch. When there was a long lapse on his part, I suspected something wrong, but a letter finally came.

“Why is it,” he wrote, “when an old cowboy gets ready to take that long one-way ride alone, he always starts talkin’ ’bout some ol’ pet horse that’s been dead for 40 years? I saw Bill Young 10 days before he crossed, an’ all he wanted to talk about was ol’ Chuck-a-luck. I went over to Globe on my vacation, met John Armer on the street. ‘Dogie Si wants to see you,’ he says. ‘The doc only gives Dogie a couple of days to live. Come on an’ I’ll go with you.’

“ ‘What was the name of that horse?’ said Dogie Si. ‘It was at the Wine Glass outfit ’most 35 years ago. I mean the pony that got his guts hooked out by the big stag. An’ the stag would a-killed you, too, if the ol’ pony hadn’t made a run on the rope an’ held it tight with his guts a-hangin’ out.’

“ ‘Smithy,’ I says.

“ ‘I knowed you’d know,’ said Dogie Si. It seemed to please him, too.

“Then John says to Dogie Si, ‘Look up Bill Young an’ Henry Jones when you get over there; they’ll know where Smithy’s runnin’. An’ find out what bunch Mormon Joe is runnin’ with — he’s the ol’ pony I want to ride when I get over there.’

“Well, Dogie only lasted a couple of days, like the doctor said, an’ I see in the paper where John Armer made his crossing, too. I reckon John’s ridin’ Mormon Joe by now. The reason I ain’t wrote before was because my ropin’ arm went dead — had to button my pants with my left hand. This is the first letter I’ve wrote with it, but my arm’s all right again. Fact is, I’m better than when I seen you last — no more dizzy spells, an’ my good eye is really good again. I think it will be some time before I start talkin’ ’bout some ol’ pet horse that’s been dead for 40 years.”

Good roper, good bronc rider, all-round top hand, always generous to a fault. I’ve been privileged to know many of his kind. Yet there was something about Shorty that always set him apart. It might have been his tolerance. Never have I heard him speak of any man unless the word was good. On the Gila, the Tonto, the Salt, they’ll retell his stories in cow camps at night, but the yarns won’t be the same. From the rim on down to the desert, Arizona’s wide ranges will miss his pony tracks.