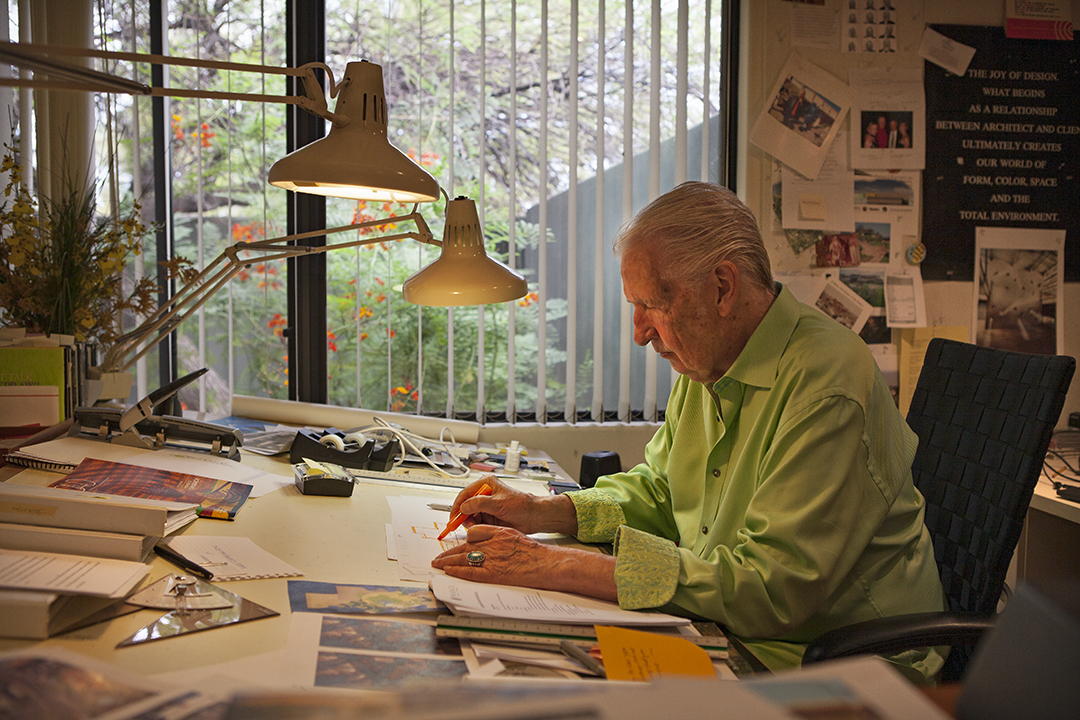

The student is a cerebral thinker, a philosopher, a visionary and a guy with a wry sense of humor. There’s no such thing as a brief conversation with him. Anecdotes, digressions, sidebars and footnotes — all of them fascinating — flow about his more than six decades in architecture. Riding out the pandemic in a North Scottsdale desert home he designed with his wife of 38 years, Vernon “Vern” Swaback spends his days working on design and planning projects for his firm, Swaback Architects and Planners; devoting time to his Two Worlds Community Foundation, a nonprofit think tank aimed at building strong communities; and finishing up his 12th book.

He credits his multitasking and creativity to one source: the two years he spent studying and working with Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin West, in Scottsdale, and Taliesin, in Wisconsin. At age 81, Swaback might be the last of Wright’s apprentices still practicing architecture. He’s happy to talk about the master architect’s influence on his career and life.

“I was raised by conservative, religious parents,” Swaback explains, “and I always thought I was to become a missionary. Well, I am a missionary, in a way. I’m still teaching people about Frank Lloyd Wright and his philosophy.”

SWAYBACK FIRST LAID EYES ON WRIGHT'S work first laid eyes on Wright’s work as a child in a musical family on the Near North Side of Chicago. His mother was a violinist, and his father directed the church choir. Swaback chose the trumpet as his instrument and saw Wright buildings as he traveled to nearby Oak Park for lessons. “Those structures radiated out to me,” he recalls. “They were different from all the other houses and buildings. I had to learn more about them.” When Swaback got to high school, his drafting teacher noticed his interest in design and steered him toward architectural studies at the University of Illinois.

In the fall of 1956, as a 16-year-old college freshman (he skipped a few grades in elementary school), Swaback found himself at an exhibition of Wright’s work at a Chicago hotel — and unintentionally “photobombed” a shot of Wright being greeted by Mayor Richard J. Daley. “Mr. Wright unveiled a plan for his Mile-High Illinois skyscraper project during the exhibition,” Swaback says. “I was blown away and knew I wanted to study with him.” At the suggestion of one of Wright’s apprentices he met at the exhibition, Swaback wrote a letter to the architect, asking to become an apprentice. A few weeks later, his parents drove him up to Taliesin, Wright’s home and studio in Spring Green, Wisconsin, for an interview.

“My parents were fundamentalist Christians,” Swaback says. “They had read up on Mr. Wright and some of the stories about his personal life, his marriages. I think they secretly hoped I would not be accepted.” But the interview went well. Swaback is sure he clinched the apprenticeship when Wright asked him why he wanted to leave the university. “To this day, I don’t know how these words came to me,” he recalls, “but I said, ‘Because they are beginning to teach preconceived ideas.’ ”

After finishing up his semester at Illinois (and promising his adviser he would return after a year), the young student stepped off a train from Chicago at the downtown Phoenix train station in January 1957, suitcase in hand. A family friend drove him across “the endless dark desert” to Taliesin West, Wright’s winter home and architectural community in the foothills of Scottsdale’s McDowell Mountains. “It was like arriving at Brigadoon,” Swaback recalls. “All those magical stone buildings were lit up like lanterns in the desert.”

The next day, the city slicker was ushered out into the desert and shown his apprentice living quarters: a red canvas tent. For the next two years, he adjusted to life in the arid outdoors and learned how the apprentices — known as the Fellowship — did everything from cook meals and fix the plumbing to work on architectural projects. He also fell into the group’s migration pattern: May through October in Wisconsin, November through April in Arizona.

He sat at the right hand of the architectural master, soaking up knowledge. “I started getting his attention by doing hand-drawn renderings of his buildings,” Swaback says. “When I would work on projects, he would sit down next to me and make marks on the drawings. Then, I would make his changes. Eventually, I had a table next to him in the studio.”

Working on such Wright projects as private residences and an opera house for Baghdad, Iraq (a design that later became Grady Gammage Memorial Auditorium, on the Arizona State University campus), Swaback soaked up Wrightian lessons: studying the nature of the site before designing the structure; using building materials in new ways; creating spaces for living, not boxes for things. “Mr. Wright was always teaching while he was working,” Swaback says. “We learned by doing things hands-on.”

The young student also learned a thing or two about life and Wright’s sophisticated world. “There were always important people coming to Taliesin and Taliesin West, especially during our weekly formal evenings, when we invited outside guests for cocktails and dinner,” Swaback recalls. “I met so many interesting people, like Henry Luce of Time magazine and [his wife, politician] Clare Boothe Luce.”

One day, Swaback was asked to meet some VIPs in the parking lot and escort them to Wright’s office. A limo pulled up, and out stepped film producer Michael Todd and his then-wife, Elizabeth Taylor, who had come to confer with Wright about designing a series of theaters for Todd’s widescreen films. “You have to remember, I grew up in a strict household and never went to the movies as a youth,” Swaback says, “so I had no idea who these people were. I said, ‘How do you do? I’m Vernon Swaback,’ thinking they would be impressed by my apprentice status.” The theaters never came to be: Not long after the meeting with Wright, Todd died in a plane crash.

Swaback also honed his trumpet talents, something encouraged by Wright and his wife, Olgivanna, both music lovers. Swaback commuted weekly from Wisconsin to Chicago to take private lessons from trumpet great Adolph “Bud” Herseth of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. The lessons gave Swaback the confidence to perform in Taliesin’s many concerts and land a stint with the Phoenix Symphony. Not that he was a musical snob: Swaback also played with Taliesin’s rock band and held his own during a mariachi concert. For years, he jammed with Phoenix jazz pianist Charles Lewis. (His most recent gig? Awakening his wife, Cille, on her special day with a rendition of Happy Birthday to You.)

The day Swaback learned of Wright’s death in Phoenix on April 9, 1959 — just short of his 92nd birthday — is still clear as a bell. “I had worked with him the evening before he went into the hospital,” Swaback says. “He was always engaged and youthful. He used his cane more as a pointer than for walking. We had no idea anything was wrong. He didn’t seem ill.”

Olgivanna took over running the Fellowship and the two Taliesin properties, and Taliesin Associated Architects was established to carry on Wright’s architectural practice. For 19 more years, Swaback remained at the fore of Taliesin’s architectural and planning work, heading up projects such as the renovation of the Arizona Biltmore after a 1973 fire. For that job, he lived on the property so the work could be done in 90 days, in time for the hotel to reopen for the season. He also worked on the subsequent master plan for the 1,000-plus-acre Arizona Biltmore Estates, as well as one in the village of Kohler, Wisconsin. While at Taliesin, he twice married and divorced Taliesin sculptor Heloise Crista.

IN 1978, SWABACK FELT IT WAS FINALLY TIME to leave Taliesin and set out on his own. “It was awful at first,” he says of making the leap. “The day before, I was walking among giants at Taliesin. Then, there I was, with a bed, a drafting table and a telephone, renting a tiny pool casita in someone’s Paradise Valley backyard. I was also the devil incarnate as far as the Fellowship and Mrs. Wright were concerned — nobody ever willingly left Taliesin.”

But time softened Swaback’s relationship with Olgivanna and his fellow apprentices. His architectural practice soon flourished — thanks to an early client, Kohler, which followed him when he went out on his own. With the addition of partners John Sather and Jon Bernhard, the firm soon grew to include 40 people and was headquartered in a Swaback-designed studio in Scottsdale. The business also spun off an interior design firm, Studio V. The projects included everything from custom residences and golf clubhouses to hotels, offices and master planning for notable Arizona locales such as DC Ranch and Phoenix’s Desert Botanical Garden.

Inspired by Wright’s teachings, Swaback often went to the nth degree to make sure he understood a site and a client’s needs. To get the commission for the visitors center and master plan for Kartchner Caverns State Park, Swaback and Sather drove to the then-undeveloped caverns in Southern Arizona and took a “tour” of the spectacular voids. “We had to go through what looked like a cabinet door and crawl on our bellies through mud, in the dark, to get to the caverns,” Swaback recalls. “I kept telling myself that I could do that without going crazy. When we finally emerged in the cave, it dawned on me that we had to go back the same way.”

Swaback also went out of his way to share Wright’s teachings and philosophies with his employees and colleagues. “There’s hardly a day that goes by in our office that Vern doesn’t mention Frank Lloyd Wright,” says Bernhard, who joined the firm in 1986. “It isn’t literally about Wright’s designs — it’s about the philosophy, the experience in a building, the color, the scale, the proportions and the volumes. Vern has taught me and others about what architecture is really about, which is the quality of life within a space.”

Wright’s onetime apprentice has also made sure he’s given back to the community, serving on the Phoenix Economic Advisory Board and on Scottsdale’s public art selection and urban development panels. Swaback was inducted into Scottsdale’s History Hall of Fame in 2008 and was honored as a Historymaker by the Arizona Historical League in 2019. He’s also gone back to his roots: In the mid-2000s, he served on the board — and, later, as president and interim CEO — of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, the nonprofit founded by Wright to preserve his life’s work and the two Taliesin properties.

Since then, much has happened at both properties. Taliesin Associated Architects, which operated out of both sites, disbanded in 2003. Wright’s archives, largely housed at Taliesin West, were moved to New York’s Columbia University and the Museum of Modern Art in 2012. Last year, both Taliesins were among eight Wright sites inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List (see World Renowned, page 44). Earlier this year, the School of Architecture at Taliesin, which offers a master’s degree in organic architecture, parted ways with the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation and relocated to Cosanti and Arcosanti — the architecture communities founded by the late Paolo Soleri, another onetime Wright apprentice.

Swaback is philosophical about the changes. “Mr. and Mrs. Wright really didn’t have a succession plan,” he notes. “The foundation was formed in 1940 to be a repository of Mr. Wright’s work. He only hoped it would last for 50 years. I think the Wrights would be impressed that both locations and his archives are still around. I gave my heart and soul to Taliesin, but things move on and evolve — some things just have a time limit.”

Nonetheless, Swaback remains steadfast in sharing Wright’s legacy with the world and is supportive of the foundation. “Vern believes deeply that the world needs Frank Lloyd Wright now more than ever,” says Jeff Goodman, the foundation’s communications director. “He sees in Wright the answer to many of the world’s challenges and is as awestruck today as he was when he was in the architect’s presence. Yes, Vern’s stories are mainly about the past, but he shares the past as a way to inform the future.”

Indeed, the future is very much on Swaback’s mind. He’s putting the finishing touches on his latest book, Designing the Future: Volume 2, in which he ponders the past, present and future of urban design, zoning, the environment and architecture. The first volume was published in 1997 by ASU’s Herberger Center for Design Excellence (now the Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts). The new volume, Swaback says, will have a preface written by ASU President Michael Crow.

His past with Wright, however, is still very much part of Swaback’s present, and he credits the two years he spent with the architect for shaping his life. “Mr. Wright was a cosmic philosopher,” he says. “He had such a unique way of looking at things. He expanded my sense of the possible. I was changed just by being in his presence.”