Katie Lee was 3 years old when her parents began picnicking in Sabino Canyon. That was in 1922. The late author and activist would become best known for her advocacy of Glen Canyon, but Sabino was her first love.

“I remember clearly the rocks, the trees, the sand and the miracle of moving water that ran over and around and through all this,” she wrote years later. “This was the first real creek I remember seeing. I wanted to know where it came from … and, even at 3 years old, who’d left the water running.”

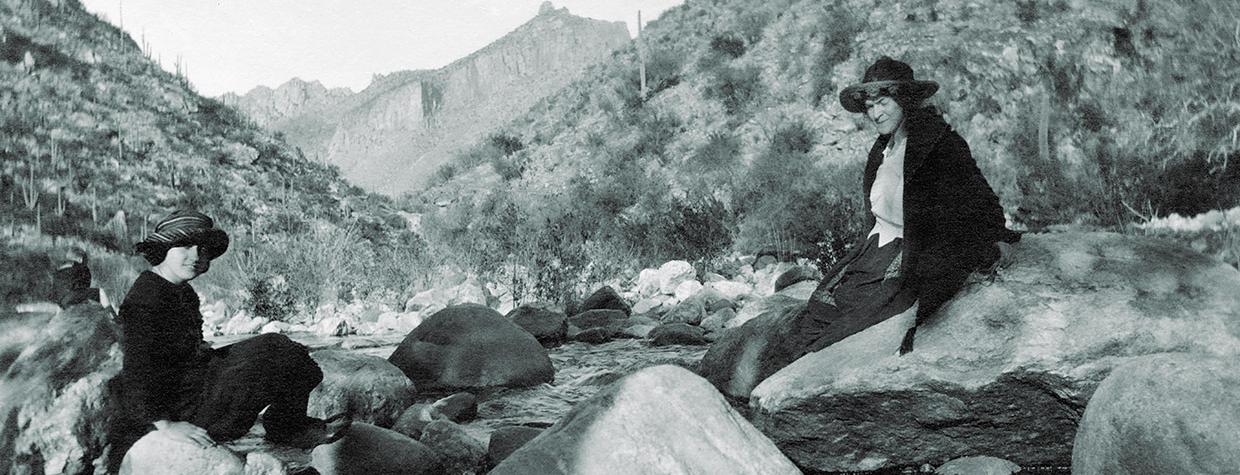

Lee was not alone in her infatuation. Tucson residents had been making pilgrimages into the canyon at the foot of Mount Lemmon since the late 19th century, traveling by horseback or buggy on Sundays to picnic at the confluence of Sabino and Rattlesnake creeks.

The early decades of the 20th century were a kind of golden age in the canyon. The route from town was familiar, well traveled and, except during very bad weather, quite safe, David Wentworth Lazaroff writes in his meticulously researched history, Picturing Sabino. “When visitors arrived,” he writes, “they stepped into a leafy oasis that must have seemed a perfect refuge from the busy desert city.”

And despite the schemes of a few ambitious men, Sabino Canyon remained much as those 19th century picnickers had found it. But that was about to change. Not long after Lee’s first forays into Sabino, the Great Depression ushered in a decade that would transform the canyon, as Lazaroff writes, “from a quaint, barely developed picnic spot into an immensely popular recreation area with all the expected amenities of its time.”

By the time it came under the authority of the newly created U.S. Forest Service in the early 20th century, Sabino Canyon had survived plans to build a resort, mine it for gold and impound its waters to supply the growing city of Tucson. But as Tucson’s economy collapsed in the wake of the 1929 stock market crash, the powerful Tucson Chamber of Commerce saw tourists as the city’s salvation — and development in Sabino Canyon as the way to attract them. The centerpiece of the chamber’s vision was a 250-foot dam about 4 miles up the canyon.

The idea wasn’t new: University of Arizona professor Sherman Woodward had proposed a dam in the same location at the turn of the century. But rather than use it to supply Tucson with water, as Woodward had proposed, chamber boosters saw a recreational lake, with boating, fishing and lakeside cabins, plus a series of camping and picnic grounds downstream. And they hoped the federal government’s newly minted work programs would provide the means.

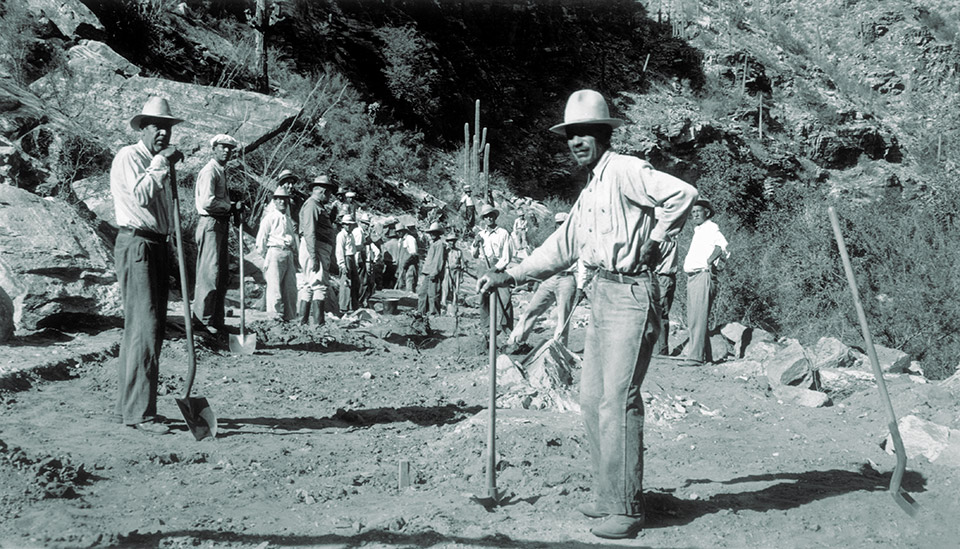

Even before details of the dam had been settled, the chamber pressed for an access road from the picnic area to the dam site. The proposed route would cross the creek in nine places, with each crossing a check dam that would create a smaller pond with its own picnic area. Federal Emergency Relief Administration crews broke ground on the new road in October 1934.

By that time, Civil Works Administration crews were already hard at work improving and expanding the old picnic grounds. In 1933 and 1934, they built restrooms, fireplaces and tables made of rounded stone pillars topped with slabs of poured concrete. They also built a picturesque two-room house for the resident caretaker, using rough-cut local stone.

“The house itself was this side of a torture chamber,” says Patti Lewis, whose late husband, Bert, lived in it as a child. “There was no running water or electricity, and it was always full of bugs. You put your bed and chairs in glasses so scorpions couldn’t climb up, but they were still dropping down [from the ceiling]. They had a really nice, big fireplace that they used a lot. That was their source of heat.”

By March 1934, Civilian Conservation Corps enrollees from the Tanque Verde Camp, east of Tucson, broke ground on a ranger station, fashioning adobe bricks on-site. Completed that summer, the Lowell Ranger Station, now on the National Register of Historic Places, served as the primary contact point for visitors until the 1960s.

The Works Progress Administration took over construction of the access road in 1935 and was within a mile of the dam site in January 1937, when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers issued its final decision on the dam. The district engineer recommended the dam be built — but, to great shock and dismay, also required that local interests contribute $500,000 toward the cost. Despite using all its political capital, the chamber couldn’t overcome that sizable price tag. Eventually, even chamber members lost heart, and plans for the dam ended as abruptly as the unfinished road.

While chamber members were still licking their wounds, Coronado National Forest supervisor Fred Winn proposed a more manageable idea. Once the WPA had taken over construction of the road, Winn had put the ERA crews to work building a recreation area downstream from the old picnic grounds. He asked: What if a more modest dam could be built there?

By the time work began on the smaller dam in June 1937, Winn had secured ERA funds for the materials. The new dam would cost the city and county nothing. By February 1938, the lake began to fill, and with great fanfare, it was dedicated in April, becoming immediately popular.

In May 1938, after the Forest Service threw a retirement party for ranger Frank Cox, the U.S. Department of Agriculture appointed H. Glenn Lewis as his temporary replacement as caretaker of Sabino Canyon Recreation Area. Lewis moved into the little rock house with his wife, Helen, and their 9-month-old daughter, Barbara. The next year, Lewis became ranger for both Sabino Canyon and the Palisades Ranger Station in the Santa Catalina Mountains, where Helen gave birth to their son, Bert. The family spent summers in the Palisades and traveled on horseback to Sabino Canyon for the winters.

“Grandpa would take both kids with him to clean up the campgrounds,” says Bert’s daughter, Dawn Haldeman. “He would tell them he thought he saw a dime or a penny on the ground and would call them over to see if they could find it. Later, they found out he was the one dropping the coins.”

A favorite family story involved the time two prisoners escaped from the work camp that was building the road to Mount Lemmon. “Grandpa was learning to use a rifle with a scope that his brother Clyde gave him,” Haldeman says. “While he was aiming at a rabbit, one of the prisoners came out and said, ‘Don’t shoot, mister; I give up.’ ”

Arming his wife with a revolver, Lewis left her in charge of the first prisoner at the house while he rounded up the second. When he returned, he found the first prisoner eating a slice of peach pie as if he were a guest.

Its projects complete, the last work camp at Sabino Canyon closed in June 1939. And while the Tucson Chamber of Commerce didn’t see its pet project completed, it did see the visitation its members had hoped for. In May 1937, men at the work camp counted more than 18,000 visitors from the U.S. and Mexico. The next year, the Forest Service estimated 125,000 visitors — more than a third of the number who visited the Grand Canyon that year.

Fred Winn’s lake eventually filled in with silt, but the spot remains popular with birders. A visitors center was built in 1963, and Friends of Sabino Canyon is currently raising funds to create a master plan for significant improvements. In the 1970s, the Forest Service closed the canyon to cars, and today, a tram ferries visitors — more than a million per year — up the canyon.

The Forest Service also demolished the caretaker’s house, although the foundation and stairs remain. And while Bert Lewis was about 8 years old when he left, Sabino Canyon had a major influence on his life. “He would always say, ‘It’s like trying to get the sand out of your shoes,’ ” Patti recalls. “And he couldn’t, because he just loved the desert and everything about it.”

Katie Lee last visited Sabino Canyon in 1957, finding it so changed that she had trouble relating to the place where she had spent so many happy hours. But she couldn’t let go of it, either.

“That particular spot on the globe cradled something important for me,” she wrote in 2007. “There’s a healing power in calling up those special places we don’t let change in our minds, even though they may have altered dramatically over the years. I can still see things along our [route] as plainly as they were 60 years ago, and I don’t need photographs to help me. I get the smell of the spring runoff, the scent of sweet, decaying leaves in autumn; I see the crystal light on huge, striated, water-worn granite boulders — can remember crawling beneath them in a rainstorm; or cooking hamburgers over pine cones, cottonwood, mesquite, ponderosa and saguaro-rib fires, each with its particular smell. … Luckily, the Sabino of my mind is forever here.”