Editor’s Note: “In 1940, I fulfilled a lifetime ambition,” Barry Goldwater wrote in his book Delightful Journey. He was referring to a trip down the Green and Colorado rivers. On that trip, he kept a journal. “This book of mine first assumed form as a diary scribbled and jotted each evening as we made camp; then it was published in a mimeographed edition of three hundred copies distributed privately among employees of the Goldwater store and my family,” he wrote. “I also adapted a small portion of the text for an article that appeared in Arizona Highways in January 1941.” In his column that month, Editor Raymond Carlson wrote: “It is with considerable pride that we refer you to Barry Goldwater’s story in words and pictures in this issue. [He] took several thousand feet of colored motion pictures and hundreds of black and white still shots. We have selected for portrayal of the exciting trip some seventy of the stills and urge you to see the motion picture if you ever have the chance.” Although that film is currently not available, plans for restoration and public viewing are underway. For more information, visit the Barry & Peggy Goldwater Foundation’s website, www.goldwaterfoundation.org. Meanwhile, enjoy this trip back in time.

When a man has an itch for the greater part of his life, there comes a time when scratching is inevitable. This particular itch can be classed as “riveritis,” and of the particular river causing the itch, there could never have been any doubt — it was our Colorado.

First symptoms of this affliction appeared years ago when, as a small boy, I learned that my grandfather started his business on the doubtful banks of the Colorado at La Paz. As the years rolled by, a desire to see and learn more of this river grew right along with me. In fact, it grew a little faster than I did, for I never seemed able to catch up with it.

By the time I was a rather large boy, I had seen the Colorado from practically every vantage point in Arizona, from the bottom of the Grand Canyon to the broad expanse of water below Yuma. In addition to this visual education, I had been absorbing what the explorers of the river had written, everything I could lay my hands on, from Major [John Wesley] Powell’s accurate account of his voyage down through the years to the Kolb brothers’ vivid and thrilling description of the river and its canyons, which they call Through the Grand Canyon From Wyoming to Mexico.

I really think that the germ that had been fomenting for so many years broke out into full-fledged itching during the many readings which I gave this latter book. Emery Kolb was no stranger to me. I had known him for a long time. I had seen his pictures and listened to his lecture and talked to him, so if anyone can be accused of bringing my affliction to the point of requiring immediate attention, it is Emery Kolb.

Having made up my mind to put this desire behind me once and for all, I was confronted with the question: How? The answer to the question was, I knew from inquiry, far too expensive an undertaking for the limits of my pocketbook. Believing that there must be someone in this broad land of ours bothered with the same urging, and expressing myself thusly to my friend Hubert Richardson at Cameron, Arizona, I learned that Norman Nevills of Mexican Hat, Utah, had made the trip and was planning another one for the summer of 1940. That was all I needed. A letter was dispatched to Mr. Nevills on the next mail, and then passed two weeks of pin-sitting, waiting for his answer. Finally, it came, and to my unbounded joy, he told me that there were eight others like myself who wanted to make the trip and that by combining our resources and our monies, the trip could be brought within the all-important limits of all of our pocketbooks.

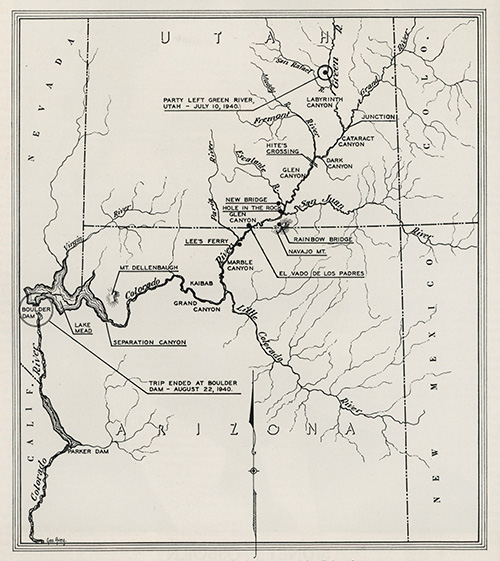

That was in January; the trip wasn’t to start until June. I wondered what I would do, trying to wait patiently for the day we would sail. I found the answer in the many problems that came up regarding camera equipment, film, personal duffel, and all the million and one things a trip like this requires. As that June day approached, I saw that it would be impossible for me to make the entire journey from Green River, Wyoming, and that my plans would have to be changed so as to allow my departure from Green River, Utah, on July 10, when the rest of the party would pass that town. That meant another month of waiting, but it soon passed, and on a hot July day, I arrived at Green River, Utah, ready for my lifelong-desired journey.

Nine of us set out that afternoon on the broad Green River from the small Utah town bearing the river’s name. Seven of them had come down from Green River, Wyoming, so the only strangers in the crowd were Anne Rosner and myself. Nine people in three small boats don’t remain strangers for long, though.

Just who was the first man ever to travel the waters of the Green or the Colorado is rather hard to determine. In the early days, there were undoubtedly trappers who made short journeys down these waters, but of them we know little, and that little is extremely inaccurate. A gentleman by the name of James White declared before his death some years ago that he made a trip on the Colorado in 1867 — that it was forced on him as the only avenue of escape from an attack by Indians who had cost the life of one of his party and threatened the others.

Fleeing down the side canyon in which the attack had occurred, he and his remaining companion found themselves on the banks of the Colorado. There, under the cover of night, they made a raft of driftwood lashed together with their ropes. On this crude craft they put out onto the waters of the Colorado. Many days later, Mr. White was picked up at Callville, Nevada, which is now covered by the waters of Lake Mead. In the course of his travels, he had lost his one companion in a whirlpool someplace in the Grand Canyon. Mr. White’s story has often been attacked and is very rarely accepted as true. However, without any comment as to why, I have always accepted his story of passing through at least some of the canyons of this river as a plausible and a possible one.

It remained for Major John Wesley Powell, a one-armed Civil War veteran, to make the first recorded trip from Green River, Wyoming, down the Green, the Colorado, and through all the canyons of these rivers, including the Grand Canyon of Arizona. On May 24, 1869, he put out from Green River, Wyoming, with four boats to travel down two rivers whose canyons had been held in fearsome awe for many years. He had no knowledge of his route. In fact, he didn’t know whether the story that the Colorado flowed underground for a part of its route might be true. He and his men completed the journey the same year in which they started it, and on their way, they acquired and set down such perfect descriptions of the rivers, and the country through which they flow, that the information has remained today unsurpassed and seldom equaled. His subsequent trips in 1871 and 1872, over a part of the same route he had earlier taken, added much to our knowledge of the geography and geology of the Grand Canyon and its country.

In the intervening years, numerous other parties have traveled down the river of canyons, and those parties have faithfully recorded all that they have seen and have even mapped very thoroughly the river and its course. Because those preceding us had done such a splendid job of exploration, there was very little left that we might contribute by the journey we were making. As we camped our first night, though, we realized that these rivers would contribute much to us in the form of unrivaled beauties of nature. Our first camp was by the side of a geyser 6 miles below Green River, Utah. The geyser had been made several years before, when a company drilling for oil ran into a gas pocket. The seepage of water into the pocket from the nearby river causes an occasional eruption of gas and water, during which the geyser becomes a beautiful fountain over a hundred feet high.Leaving our first camp early the next morning, we continued our travels on the broad Green River. Our boats had been splendidly made by Mr. Nevills during the winter and spring months. The results of his labors incorporated all that he had learned from the success and failure of others about how boats for river travel should be built. The boats were 16 feet long and made of half-inch plywood. At the widest place, near the center of the cockpit, each boat measured 6 feet. Empty they weighed about 600 pounds, and fully loaded they approached 1,200 pounds. This weight caused the boats to draw about 8 or 10 inches of water. Two-thirds of each boat consisted of watertight hatches, leaving a small cockpit in the center where the oarsman sat. The oarsmen had nothing to do in the quiet waters of the Green, for we used an outboard motor on the lead boat and tied the other two behind. Thus we went on down the rivers to see the things Powell and the Kolbs had described so graphically.

Evidence of habitation was seen on every hand. Until we plunged into our first canyon, Labyrinth, below Green River, Utah, we saw farms at almost every mile. Then, when we were in the canyon, many cattle trails put in their appearance, evidently coming down from the plateaus above. Shortly after passing the Butte of the Cross, which Powell had so perfectly named, we found the remains of a cabin at Yokey’s Flat. Some rancher had evidently built this small house and its accompanying granary as a fly camp for his cowboys and then abandoned it, for it was clearly apparent that no one had lived in it for some time. After this place, our avenues of contact with habitation consisted only of cattle trails, as we were fast entering the least-known portion of the United States and a section of our country that has naught to offer either man or beast but unrivaled scenery. We loved it, but I guess the cows aren’t as appreciative as we, for we saw none of them on their trails.

One of the most interesting places we passed was Bowknot Bend. Powell gave it that name, but even if he hadn’t, someone else would have, because there is nothing else to call a perfect bowknot except a bowknot. Here the river describes two loops in the form of a bowknot. At the gather, or small place in the knot, all that divides the river is a high sandstone wall not over an eighth of a mile thick at the bottom and rising about 800 feet above the river’s edge. The river could take a shortcut through this ledge and save itself a lot of traveling, for it goes

7 miles around the loop of the knot.

On downstream from this spot, we stopped at and entered Hell Roaring Canyon. That is a terrible name to put on such a beautiful side canyon, and the man who so named it must have been in a bad mood that day, for I could easily think of nicer names for this spot. It was interesting to us, though, for in this canyon, the mystery man of the river has inscribed his name.

One Denis Julien passed this way around 1836 and left five inscriptions scattered along the walls of the canyons of the Green and Colorado rivers. That he was a trapper has been fairly well determined, but what became of him after making this voyage has never been discovered. If other inscriptions of his are ever brought to light below his last known one, in Cataract Canyon on the Colorado, then to D. Julien must go the credit for being the first man to travel this way.

After spending four days following the crooked course of the Green through Labyrinth Canyon, we came to the junction of the Green and the Colorado. This junction lies at the end, or mouth, of Stillwater Canyon, a small canyon through which we passed on our last day on the Green.

Prior to 1921, when the Colorado state legislature changed its name, the river above this junction, which is now known as the Colorado, was called the Grand. However, no law in the world can remove from the minds of those who have traveled and loved this river the fact that the Colorado is formed in a deep and lonely canyon in Eastern Utah where the Green and the Grand run into one another. Probably no important stream in the world can boast of as many names as can our Colorado.

In 1540, [Hernando de] Alarcón named it Río de Buena Guia, or the “River of Good Going.” [Melchior] Díaz in the same year saw it, and his name for this river was Río del Tizón, or the “River of Firebrands.” The next visitor was [Juan de] Oñate, who in 1604 came upon this river at the point where the Bill Williams empties into it in Arizona. His name for it was Río Grande de la Buena Esperanza, or the “River of Good Hope.” Padre [Francisco] Garcés, that much-traveled father, came upon this river and named it Río de los Martyrs, of which [Dr. Elliott] Coues says: “This was prophetic, for in 1781 at or near the mouth of the Gila, Garcés and three other priests were murdered by Yuma Indians.” It has also gone under the names of Río Colorado del Norte, Río Colorado del Occidente, Red River of the West, Red River of California, and the Indian name of Hakatai. Just who first called the river “Colorado” and when it was so designated has never been determined. The present name means “red,” and if one has seen this rolling torrent of red mud “too thick to drink and too thin to plow,” one can understand the reasons for its being called Colorado.

“We have an unknown distance yet to run, an unknown river to explore. What falls there are, we know not. Ah, well! We may conjecture many things. The men talk as cheerfully as ever; jests are bandied about freely this morning; but to me the cheer is somber and the jests are ghastly.”

— John Wesley Powell

During our 120-mile trip from Green River, Utah, to the junction, we had nothing but the calmest of water over which to float. Now, though, things were to change. We could hear the ominous roar of the first rapid, at the head of Cataract Canyon, all during our lunch, and then when we moved down a mile to a point just above Cataract’s yawning chasm, the roar became as 10 Niagaras.

An hour spent at that point sufficed to caulk the boats and store all loose equipment, and we were ready for our introduction to the rapids that have made this journey such a famous one. Soon, everything was prepared and our lead boat shoved off. I was a passenger on this boat, and my particular position was lying down on the rear deck. Mr. Nevills had the oars, and his wife, Doris, sat in the front of the cockpit. All of us wore life preservers, as we did through all rapids. My formal introduction to a rapid was a most complete one. Although that rapid at the head of Cataract was a baby compared with what was to follow, still there was a hole in it that we went through, and so far underwater did my end of the boat go that I could swear there was gravel in my hair from the bottom of the river when we finally emerged.

Cataract Canyon is a short one, being only about 50 miles in its entire length, but it seemed to us that every mile had several rapids in it, and rare indeed was the stretch of water that we could term quiet. This canyon was the first of the really deep canyons we were to find. At its head, it is about a thousand feet deep, and there are places in its length where the canyon walls flirt with 2,500 feet. I doubt if there is a place where this canyon is more than 3 miles wide, so we were, so to speak, in the center of the Earth, with only one safe way to get out.

We had gone on this “safe” way for several days and had gone skipping over the rapids as if they weren’t there, and from this easy traveling, we had probably picked up a tinge of disregard for this river and its vaunted strength. Now, tipping your hat to this stream is a better way of getting along than thumbing your nose at it, and although we always tried to remember that, perhaps on Mile 24 Rapid, it had slipped our minds momentarily.

The first two boats to navigate this rapid came through with flying colors, but the third, by accident, got on the wrong side of the tongue leading into the rapid, and boat No. 3 was firmly wedged between two large boulders in the center of the rapid. Rescue was accomplished by rowing one of the other boats out into the back eddy at the bottom of the rapid, and then jumping from rock to rock until we arrived at the lower of the two big rocks that held the boat fast. With the combined strength of three men, the boat was dislodged among shouts of happiness from all of us, but the happiness was short-lived.

As the boat went downstream, it struck a rock, which set it on its side, and from that position, it went on over. It was only a matter of a half-mile or so until John Southworth and Dr. [Hugh] Cutler had rescued the overturned boat and pulled it to shore. They found all the duffel and bedding in the forward hatch soaking wet, water having poured through a gaping hole torn in the deck of the boat. As if to add insult to injury and to further discomfit those whose bedding was wet, it rained all night.

Two delightful days were spent in the coolness and dryness of Dark Canyon. We explored this canyon, without success, for Indian ruins, pots and arrowheads, and then proceeded on our way down to the end of Cataract. On passing Mile Crag Bend, which marks the end of Cataract Canyon, we went immediately into another one, called Narrow Canyon. This small canyon is only about 10 miles long, and shortly after we entered it, the rapids disappeared and quiet water came again. Narrow Canyon ends at the junction of the Frémont with the Colorado. This river coming in from the west had an unusual name for a while. When Powell came this way in 1869, one of his men was looking up this side stream and Powell yelled over to him, asking what it looked like. The man called back that it was a “dirty devil,” and that name stuck until it was changed to Frémont in honor of General J.C. Frémont, who was one of Arizona’s Territorial governors.

Canyon follows canyon on this route, and as we left Narrow Canyon, we entered Glen Canyon, down which we were to travel until we reached Lees Ferry. Our first cache of food and mail awaited us at Hite’s Crossing, 6 miles down from the head of Glen Canyon. Here, the canyon is very wide and shallow, as is the river itself.

In the 1880s, this place was settled by the Mormons, who used it as a crossing place or ferry. It became a small town, a post office was established, and then, in 1926, people just up and moved away and the embryo town folded. Today, a mile downstream from the ruins of this settlement, live Mr. and Mrs. A.L. Chaffin, who operate a small farm. We enjoyed their hospitality for three days, and it was with reluctance that we put out again on the river. While at Chaffin’s, we learned that [President Franklin] Roosevelt had been renominated and that the British were still causing [Adolf] Hitler a lot of grief. The absence of news was one of the nicest things about the trip.

Our first river camp in Glen Canyon was under the towering heights of Tapestry Wall. Its 1,200-foot height made a perfect west wall for our bedroom, even though it didn’t stop copious quantities of sand from bothering us all night by blowing in our ears, mouths and eyes.

If this trip was to accomplish anything other than enjoyment, it was to locate and measure a natural bridge of which Dr. Gregory of Honolulu had told us. Following his instructions carefully, the bridge was located 8 miles up the Escalante River and 1.5 miles up a side canyon. Measuring it, we found it to be 306 feet high, 193 feet wide, 114 feet thick at the top and 192 feet from the floor of the canyon to the bottom of the arch. It in no way compares with the Rainbow Natural Bridge in beauty, and, after taking the measurements, we returned to the boats to continue downstream. Both Nijoni, which is Navajo for “beautiful,” and Gregory have been suggested as suitable names for the bridge, but as yet, it has not been officially named.

A few miles below the mouth of the Escalante, we approached what was to prove one of the most interesting of all the spots we were to see. Hole-in-the-Rock Canyon didn’t look a lot different from other side canyons, except that it was exceptionally short, steep and narrow. The difference lay in the romantic history of the place.

In 1879, John Taylor of the Mormon Church visioned that his people should go to the southeast and settle the valley of the San Juan. November of that year saw 250 men, women and children depart from Cedar City in 82 wagons, accompanied by nearly a thousand head of cattle. Five weeks had been planned for the entire journey, but at the end of that time, the party found itself on the plateau above Hole-in-the-Rock, its travel having been impeded by the many canyons, deserts and rivers it had to cross. As I stood there at the head of that narrow crack in the Earth’s surface, I could well imagine the feelings those Mormons must have had when, after all the hardships of travel they had already endured, they were confronted with this new one.

The river they had to cross lay a thousand feet below them, a mile away, down a steep canyon whose entrance wasn’t wide enough to allow the passage of the wagons. Following the amazing pioneer instinct of never admitting defeat and of never turning back, they pitched in to make a road down this canyon. Working with the zeal that has always been peculiar to the Mormons, they cut steps in the canyon’s floor, widened the walls where need be, built a road where there was dirt enough to allow such construction, and even made a bridge at one point. All this work was done in the bitter cold of December and January.

Finally, late in January of 1880, the first wagon made the descent down Hole-in-the-Rock with the aid of 20 men holding it back and the animals in front straining to act as brakes instead of power. That successful day saw over 20 wagons taken down that trail, built by the determination of people going someplace to do something, and ferried over the Colorado, on rafts built for that purpose by men not engaged in the construction of the roadway.

Finis was written to this venturesome trek when the entire party arrived, in April of 1880, at the spot where Bluff, Utah, now stands. As our boats drifted away from this spot, I felt a thrill at having stood on ground made so historic by those people. I could see wagons being ferried across the river, with cattle swimming after. I could see the tired faces covered with the smiles that come to those who have tried and conquered. And as the current carried us around a bend and away from sight of Hole-in-the-Rock, I tipped my hat — not to a place of beauty, even though this canyon can fall under that description, but to the courage, the will, and the zeal that drove these people on to the accomplishment of their mission without the loss of a single life. Our West was built by people like those Mormons, and the ground they traveled should be forever a shrine for those who follow.

A few miles downstream, we passed the mouth of the San Juan. This river comes in from the east, out of a good-sized canyon of its own. It is one of the largest of all the tributary streams. It rises in Colorado, and then, skirting through New Mexico, it flows across the southern end of Utah to its junction with the Colorado in Glen Canyon. Much of the red silt from which the river gets its name comes from the San Juan.

This seemed, indeed, to be an unusual day, and our luncheon spot that noon didn’t mar the beauty of the day that had had so perfect a beginning. Approaching Narrow Canyon, we wondered from whence it got its name, for from the river, it looked wide. After tying the boats at its mouth and going back into it for a few yards, though, we discovered it to be but 30 or 40 feet wide. The walls rose above us 800 feet, and on the floor of this delightfully cool canyon flowed a small, clear stream of water, coming down from the mesas above and winding its way through the canyon to add itself to the muddy waters of the Colorado.

If there is a hallowed spot on the river, it is Music Temple, which lies just across the river from Narrow Canyon. Powell, on hearing the wonderful quality that this tremendous cavern imparted to the voices of his men singing around the evening fire, named it Music Temple. Today, that spot is sacred to those who travel the river. On the walls are carved the names of the members of Powell’s expedition, and in reverence to those hardy men, no one has since carved his name there. Instead, one writes his name on a piece of paper and places it in a can provided for that purpose.

Evening of that eventful day found us at the mouth of Forbidden Canyon, under the blue heights of Navajo Mountain. We had all looked forward to arriving here, for we knew that just 4 miles up Forbidden and then 2 miles up Bridge Canyon, we would come to the Rainbow Natural Bridge. All of us had been there before, and we, like all others who have visited the spot, carried an ever-present desire to pay the Rainbow another visit. I was doubly eager, for not only was the bridge itself acting as a magnet, but, better yet, I would see Katherine and Bill Wilson, and I knew they would bring news from home.

For me to attempt a description of the Rainbow after the way Irvin Cobb did it would be foolhardy. I’ll hold up my description of that delightful spot until people forget Cobb’s, and I feel that I’ll never have to offer mine, for his will be the best long after I am gone. The story would not be complete, though, were I to fail to mention that we did spend four days at the bridge and four nights of sleeping on real mattresses free from bugs of all descriptions.

Glen Canyon has always been synonymous in my mind with the unusual, the beautiful, and the historic. Each of these attributes had unfolded itself before my eyes, but the canyon was by no means through with its interesting parade. As we approached Kane Creek, one could see that it might be possible for a ford to exist here, for the banks on both sides were low and sloped gently back from the river.

Just a short distance below Kane Creek, Padre [Silvestre Vélez de] Escalante and his group crossed the river in 1776, returning from an unsuccessful attempt to locate a shortcut to California. He had gone to the junction of the Paria and the Colorado below this spot, but found the river too wide and deep to allow crossing there. Indians told him of the crossing farther to the north and offered to guide him there. His journey from the Paria here was not an easy one, for the route lay over slickrock, with very little water or shade to be found along the way.

However, with the customary zeal of the padre, he pushed on, and, traveling down the short canyon that now is known as Padre Canyon, he reached the river and made a successful crossing. This place has been similarly used by the Indians and by the Mormons since. While it is known as El Vado de los Padres, it appears on some maps as the Ute Crossing. Dr. [Russell] Frazier of Salt Lake City has appropriately marked this canyon with a neat bronze plaque setting out the deed of Padre Escalante.

Late this same afternoon, someone announced that we would soon be in Arizona. I had to smile, for I had suspicioned it for some time. The sky was getting a very familiar blue tint to it, the clouds were getting whiter, the birds sang a little more sweetly, and the air smelled familiarly exhilarating. No one needed to tell me I was getting home again, and no one in those boats could have felt the happiness that was mine.

Earlier than usual the next morning, we were up and on our way, for we knew that by hard traveling, we could reach Lees Ferry and more mail from home by noon. Sure enough, just before the sun was midway in the heavens, we came out of Glen Canyon, after having been in it for 160 miles, and into the rather broad valley that lies at the junction of the Paria and the Colorado. Lees Ferry is such a historical spot in Arizona that a story the size of this one could be devoted to it alone.

Rotting on the muddy bank of the river are the remains of the last boat to attempt commercial navigation of the river. The craft was built in San Francisco in 1912 and taken apart to be carried by pack train to the mouth of Warm Creek, where it was again assembled. It was to be used to haul coal from Warm Creek to the mine at Lees Ferry, but after one trip, they discovered that it took all the coal they could haul down to run the boat back upstream again, so the venture was abandoned.

To this secluded spot came John Lee, a fugitive from justice, in 1872. It was believed that he was the instigator of the heinous Mountain Meadows Massacre of 1857, in which over 120 people were massacred by Indians in Southern Utah. Blame had to be placed somewhere, so, rightly or wrongly, it fell on the shoulders of John Lee. He stayed in this lonely spot for two years, until one day when, in a Southern Utah town for provisions, he was taken prisoner.

A trial was held in which Lee was judged guilty and was sentenced to death. On March 23, 1877, Lee was seated on the edge of his coffin, blindfolded, and executed by a firing squad. As his body fell back into his coffin, justice had presumably been done. Whether or not it was justice, I am in no position to say. I have merely related the facts concerning this lonely spot in Arizona to which John Lee gave his name. Until 1927, when the Marble Canyon Bridge was built, this crossing served the travelers, first by wagon and then by automobile, who wanted to go from Arizona to Southern Utah.

Looking downstream from the junction of the Paria and the Colorado, we could see on the west the towering heights of the Vermilion Cliffs and on the east the red of the Echo Cliffs. Cutting the plateau between the two is the narrow slit known as Marble Canyon. Powell named this canyon from a marble-like structure of rock that he found in the walls of the canyon. For almost its entire length of 69 miles, this canyon’s floor is festooned with rapids, and there is hardly a mile in which the roaring music of these rapids doesn’t bounce from wall to wall to warn the traveler of what is to come. The river has cut deep here, deep and narrow. Like Cataract, this canyon is but 2 or 3 miles wide at the widest spot, but it differs from Cataract in the steepness of its wall and the coloring thereof. As soon as we were well into this gorge, we knew we were approaching the father of all canyons from the beautiful shades that the rocks were assuming.

As a respite from the work and wetness of the rapids, we had new beauties unfolded before our eyes every hour of the day. The most unusual waterfall I have ever seen is at Vasey’s Paradise. This water comes pouring out of a 30-inch hole in the solid rock of the canyon wall to tumble through ferns and moss into the river 125 feet below.

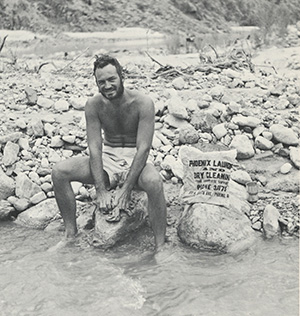

The approach to this garden spot is heralded by a large cavern whose walls are tinted in soft blends of white and red, and before that by a canyon known as Paradise Canyon, whose ruggedness is in direct contrast to the beauties to follow. Vasey’s Paradise gave us a much-needed place for baths in cold, fresh water. If you have ever been drenched by the mud of the Colorado and then had it dry on you, you no doubt have picked up a good idea of what the inside of a weenie must feel like. Small wonder, then, that these clear streams from side canyons were welcome to us. At least for a few hours, we could feel clean.

From Lees Ferry on, we expected very little quiet water, so from there we shipped the outboard home and relied solely on our oars and the current for our progress. These oars aided tremendously in the rapids. By a strong pull to the right or left or back upstream, we could maneuver our boats around rocks and holes that blocked our way. Until the Kolbs came down the river, boats went through rapids bow first, but the Kolbs experimented with and introduced the method, now in vogue, of going through stern first, so as to allow the boatman to see what is coming. This method is far superior to the old one, and it served us admirably.

At the side canyon of Nankoweap, we entered the Grand Canyon National Park. Here, too, we got our first glimpse of the North Rim, or the Kaibab Plateau. As we entered the park, I couldn’t help wishing that James O. Pattie, the first American to see this canyon, were with us. He wrote of the Canyon: “A march more gloomy and heart wearing ... cannot be imagined.” Then, for good measure, I would like to have had Lieutenant [Joseph] Ives along. He, in 1857, said, “Ours has been the first and will doubtless be the last party of whites to visit this profitless locality.” Yes, I would like to have had them there to tell them that this “dreadful place” will have nearly 400,000 people visit it this year and that they will come in nearly 100,000 cars and not a few trains and airplanes.

“With some feeling of anxiety we enter a new canyon this morning. We have learned to observe closely the texture of the rock. In softer strata we have a quiet river, in harder we find rapids and falls.”

— John Wesley Powell

The Little Colorado enters this canyon at the point where Marble Canyon ends and the Grand Canyon itself starts. It, too, has a good-sized canyon running from Cameron to its junction here with the Colorado. All else though, faded from our minds at this point. We were in the Grand Canyon. All that we had planned, all that we had done, all that we had seen paled into insignificance upon our entrance into this masterpiece of nature. The long, slanting rays of a setting sun added to the glory and softness of the colors of the Canyon as we made our first camp in the Canyon at the foot of Tanner Trail, under the Hopi Tower.

The tall formation of Wotans Throne in the immediate foreground, and the dim blue of the Kaibab in the distance, saw us off early the next morning for Phantom Ranch. In keeping with the peace of the early morning, we had no rapids for several miles, but our comfort and dryness didn’t last long. The rapids came in quick succession, once they started — first Unkar, then Mile 75 Rapid, and then the dreaded Hance Rapid.

The lowness of the water laid bare the sharp rocks of Hance, and our course down that bit of wild water was not unlike the course of a corkscrew. Our rapids so far had been in broad parts of the canyon bottoms, and if need be, we could walk around them, but when we came into the Inner Gorge and to the head of Sockdolager, the picture changed. We found that in this narrow crack in the very bottom of the Grand Canyon, the hard, slick walls went up vertically from the water’s edge. We had to ride through the rapids whether we wanted to or not. The added weight of passengers made rowing very difficult, and we bounced from rock to rock instead of adroitly missing them, as we had up above. These hardships meant nothing to us, though, for we were straining to reach Phantom Ranch that evening, and by dint of continuous rowing and by running rapids without the usual long study, we reached that spot late in the afternoon.

Fred Harvey has provided a bit of heaven in the bottom of the Canyon, at the junction of Bright Angel Creek and the Colorado, in the form of Phantom Ranch. Here we rested for three days, cooled off in the pool, cleaned cameras, and wrote letters home — and, in turn, read those that had come in to us.

We continued in the Granite Gorge, and the rapids, instead of diminishing in their fury, seemed to become more alive, as if to play with us harder than ever during our last few days on the river. This narrow avenue of rock through which we were going was a spectacular and beautiful sight. The black of the metamorphic schists is shot through with pink and coral streamers of granite. Here, on both sides of us, were remnants of a mountain range once higher than the Alps, but now worn down to its present height of about a thousand feet. Above the rim of this Inner Gorge, there appeared an occasional tall peak named after some deity of one or another of the religions of the world. As the sun set each night in the Canyon, peak after peak would drop its bright colors and take on the somber hues of night, and the last to succumb to the slow creeping of darkness would be those very highest points so many thousand feet above us.

Not all of our route lay through this granite, though, and as the Canyon swung to the north, around Explorer’s Monument, we left these hard rocks and went into the Tapeats sandstone. Here, the traveling was delightful. Long, sluice-like stretches of water whisked us downstream at a much faster rate than we had experienced above. In this formation, we went through Conquistador Aisle, which is named after the men who accompanied [García López de] Cárdenas when he became the first white man to see this Grand Canyon, in 1542. Where he first saw it has always been a debatable point. I will not enter into that debate here. I will only state that I am happy he did see it and give to the world its first knowledge of our Canyon.

This fast progress through the soft rock was to end, though, for when the river again turned south, we entered the dreaded granite, and once more, we were bouncing down rock-strewn rapids. This phenomenon repeated itself. Whenever we turned to the north, we left the granite, and as our boats would head once more to the south, we would find our enemy, the granite, waiting for us.

In this section, we came on many wonderful streams flowing down from the north, adding their welcome, cool beauty to those we had on every hand. Tapeats Creek, running at almost river size, provided interesting exploration for a few hundred yards up its course, until a too-narrow canyon blocked further progress. Then, down the stream a few miles, Deer Creek ended its mad dash from the north by plunging from its 4-foot-wide canyon down a hundred feet to the cool pool below before running on out to the river. These refreshing streams and falls were eagerly looked forward to by all of us. The extreme degree of high temperature we had to endure required occasional breaks such as these cool waters afforded. Not once on the entire trip did the thermometer go under 100 in the daytime, and many days, it flirted with 125.

Lovely and interesting side canyons continued to end themselves in the deepness of the Grand Canyon. The lengthening shadows on the walls above Kanab Creek were a sight not soon to be forgotten, and the cool, granite-strewn floor of Spring Canyon gave us a pleasant campsite, but we had seen only the preliminaries to the most beautiful of all the side canyons.

At noon one day, we came to the mouth of Cataract, or Havasu, Canyon. Here, out of a narrow, white, limestone-lined canyon, came the blue waters of Havasu Creek. We attempted to walk the 9 miles up this deep canyon to the Havasupai Indian Reservation, but to no avail. The knee-deep wild grapevines, the prickly pear plants, and the catclaw pulled us back at every step, so after a few miles, we gave it up and returned to the river.

But a few days remained now until our journey would end. With its ending would go not only the river, but also the pleasant associations. For the first time in history, two women, Mildred Baker of Buffalo and Doris Nevills of Mexican Hat, would have made the entire trip from Green River, Wyoming, to the dam. Anne Rosner accompanied the party partway. Of these three women, enough cannot be said: Their sportsmanship, their geniality, their willingness to do a man’s job and grumble less than the men, and the fact that they did all the cooking and most of the camp work places them beyond mere words of praise. In fact, the women worked and the men played.

The most remarkable thing, to me, all the way through the Grand Canyon was that at no place did one have the feeling that one was in the world’s largest canyon. Where we were able to see both rims, they would seem so far away that they looked like mountains. In fact, my impression all along, except when we were in the deepest gorges, was that we were going through a wide, deep valley.

As we approached Separation Canyon and Separation Rapids on our last day on the river, we saw protruding from the right wall of the Canyon a stick. From the stick hung a bottle, and to call attention to this was a pair of white men’s shorts waving in the breeze. In the bottle we found a note telling us to pick up two men whose outboard, in which they had come to the head of Lake Mead, had been washed downstream by a flash flood in the river. Sure enough, we found the men at Separation Rapids and took them aboard.

It seemed strange to me that a place named Separation 70 years ago by Powell to mark the spot where three of his party separated from him should now mark the separation point of the muddy Colorado and Lake Mead.

The river seemed so at ease as it flowed into the calm waters of the lake that it was like a tired giant resting after the hundreds of miles he had run, cutting deeper into the Earth’s surface at every step. All the water that we had been over and through now rested behind the strength of Boulder Dam, to be used as man wants it. It was like our journey: All the happiness, the work, the play, the hardships and beauties of both scenery and friendship were forever stored behind the dam of our memories, to be taken out and used when we saw fit.

Nine tired and happy people climbed aboard the government launch that last afternoon near the head of Lake Mead, and as we headed down the lake, I thanked the good providence that had allowed me the desire and the determination to make this trip. That evening, as we sat on the afterdeck of the speeding boat, the setting sun made white the foam splashing around our boats, creating a strange contrast with the blue of the lake. Above this contrast, from the stern of the government boat, waved the flag of our country, and I thought of the men in Europe who couldn’t make a trip like this one ... then said goodbye to the Colorado, glad I had seen its wonders in the American way.