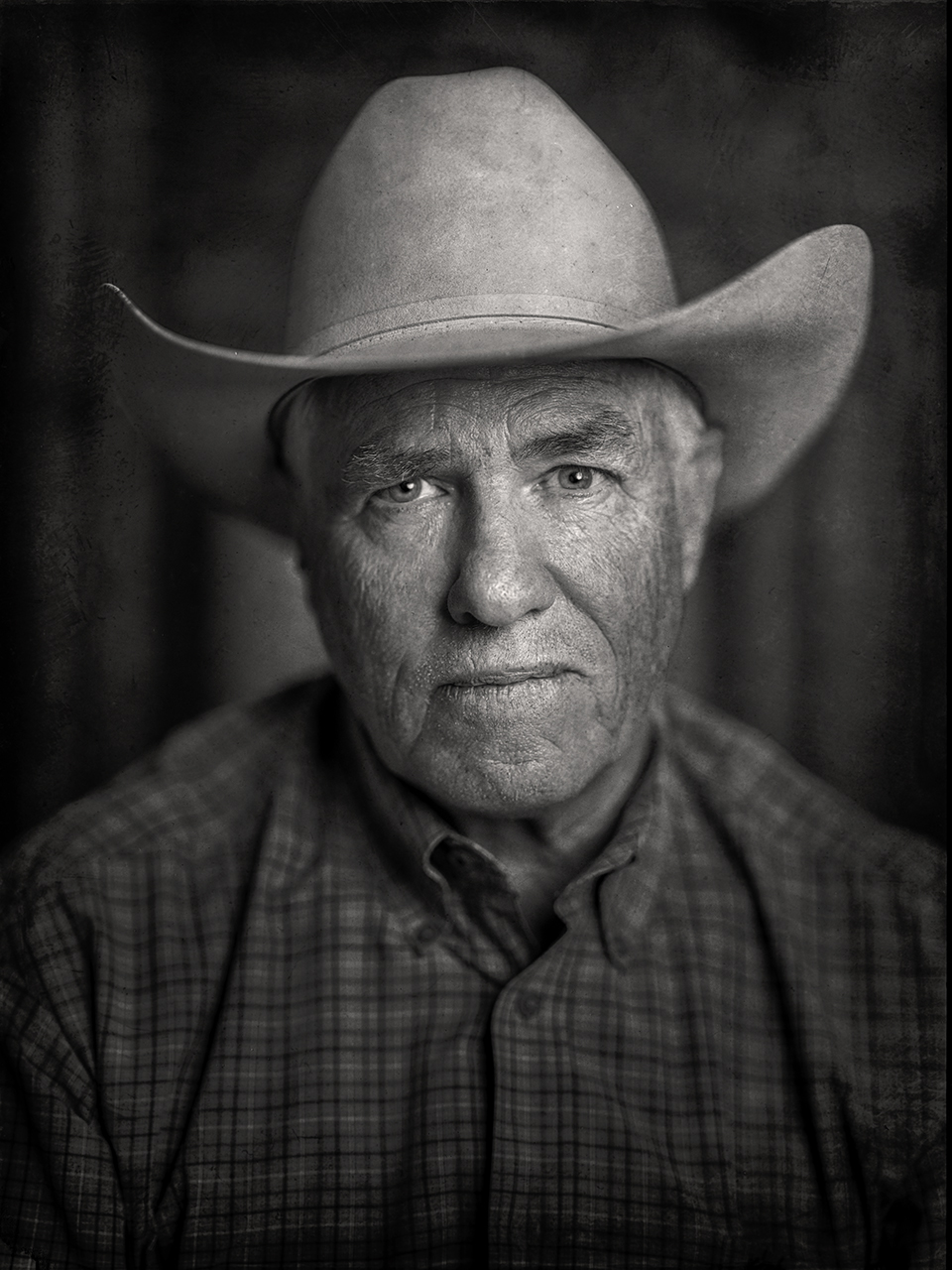

Bill Anton is unsettled.

On the first Saturday in August, a wildfire is burning near Kirkland.

The Dragon Bravo Fire continues to rage on the North Rim of the Grand Canyon, and the echoes of the Yarnell Hill Fire, which killed 19 hotshot firefighters on June 30, 2013, hang over the state, as they have for more than a decade.

But Bill (pictured), who has been painting professionally since 1982, is also thinking about the Doce Fire, which ignited on June 18, 2013. That one forced him to evacuate his home and studio, which sits in the shadow of Granite Mountain and on the edge of the Prescott National Forest, just outside of Prescott proper. It’s the home he shares with Peggy, his wife of more than 40 years. It’s the home where their two children grew up. It’s the home whose walls are lined with Bill’s paintings, among others he’s acquired from mentors and contemporaries.

“Doce was a serious fire,” he says. “I have pictures of it that you wouldn’t believe, because we had a front-row seat. We were evacuated for about five days, and we weren’t back in the house for three or four days before the Yarnell Hill Fire started. We had a thunderstorm the afternoon of the 30th. The mountain was ash by then because of Doce, but we were sitting out here. We’d had about a quarter-inch of rain, and usually the winds and temperatures calm after something like that. But after that rain, nothing but a hot wind was blowing. Peggy and I looked at each other and commented on how strange it was.”

In retrospect, Bill believes that’s when the Granite Mountain Hotshots were lost.

“It was about 4:45,” he says. “I had a horse that was colicking, so I was loading him in a trailer and driving him around. I didn’t even know about the Yarnell Fire at that point. And I saw on the horizon — I’m very sensitive to color — so I realized I was seeing smoke and not a cloud. I knew there was a fire over there.”

Later, as he and Peggy watched the news in their living room, they learned what had happened. And now, on this Saturday in August, Bill is worrying about how dry things are — as the state experiences what the Arizona Department of Water Resources calls an “exceptional long-term drought.”

So, as much as Bill might want to get back into the studio to continue painting, he’s at least as concerned about that fire near Kirkland. Because for him, the landscapes of the West aren’t just the subjects he’s been portraying throughout his illustrious career. They’re the driving force in his life.

AS A KID IN CHICAGO in the 1960s, Bill had plenty of opportunities to explore the city’s diverse cultural scene.

“I had four siblings, and it was a pretty great childhood,” he says. “I do remember being introduced early and often to museums and fine things, which I didn’t — at the time — really appreciate. We went to the Field Museum, and we went to the Art Institute. My parents had a little cabin up in Northern Wisconsin, so we spent summers up there fishing and things like that.”

But when Bill was 7, his family made a trip out West.

"My mother and father were very different people from each other,” he says. “They were crazy about each other, but my dad was an athlete and a practical joker, and my mother [an author] was very educated. But they laughed a lot.” They left Chicago and spent a night in Bismarck, North Dakota; the next day, they came into Montana’s Glacier National Park in the middle of the night. “I woke up the next morning and went into the parking lot,” Bill recalls. “My dad gestured for me to go stand next to him. I thought, Oh, boy. Now what have I done?”

But rather than talk to him about some youthful indiscretion, Bill’s dad, who ran a food brokerage firm, implored him, simply, to look. The landscaped enveloped him.

It was, Bill says, a seminal moment.

“I had never seen anything like that,” he says. “I couldn’t understand why we lived in Chicago when there were places like that. So, I spent the next 12 years figuring out how to go West again.”

The same year as the Glacier trip, Bill’s sister, 15 years older, married a commercial artist. For Bill, who had long filled sketchbooks with drawings and doodles, the proximity to a working artist was formative, too.

“I was already drawing, and I had a penchant for it that people sort of talked about,” he says. “But I always thought that all kids could draw, and that’s true to some extent. But when I saw the West and I was already into, or at least I had an ability for, that sort of thing, those two loves just kind of united.”

Back in Chicago, Bill’s inclination to draw waned as he pursued sports and friendships, went to school, and maneuvered the triumphs and challenges of American adolescence. He played baseball from age 9 to 18, and in so doing, he says, he ruined his knees. And when he got sick and couldn’t do much of anything, he asked another sister to find a sketch pad for him.

“I was sort of surprised by what the years had given me, because I hadn’t drawn since I was a little kid,” he remembers. “So, I picked it up again. And then I started copying the Marlboro ads out of magazines, because the imagery was so compelling to me that I thought, Boy, this is really something.”

At 19, Bill was studying at Chicago’s Loyola University when his father died. He knew then that he didn’t want to stay in the Windy City. An adviser directed him to a “nice little school in Flagstaff.” Within months, Bill had packed his bag and made the move to Northern Arizona University.

“I love sports, and I love the food,” he says, “but Chicago was 1,000 miles away from where I wanted to be. I had never been to Flagstaff before, and I didn’t ski, but I knew I didn’t want to go to school in Montana. So, I transferred to NAU. It was fabulous. And that’s where I met Peggy.”

Although he studied English in college, Bill continued to draw and paint, focusing particularly on Western art. He says he “stumbled” into the 1978 Cowboy Artists of America show at the Phoenix Art Museum as an observer. There, he realized people were actually making a living through their art.

But Bill considered himself practical. His initial plan was to work long enough in his family’s food brokerage business to become somewhat financially established, then move back out West to try to make a jump into fine art. But that plan quickly unraveled — he made it in Chicago for six months.

“I realized that the time to do that is not when you have a mortgage and children,” he says. “The time to do that is when you have nothing to lose. So, I did it when I had nothing to lose. And I couldn’t have done any of it without Peggy’s support.”

The two were married a few years after he returned to Flagstaff. “About 15 years later, I asked my in-laws if that decision bothered them at the time,” Bill says. “Peggy’s a fifth-generation Arizonan, and her family was very established in the state. I’m just an idiot from Chicago. They said that it did [bother them], but they never said anything.

“I couldn’t believe it, but it worked out right from the beginning.”

AS BILL SITS ON A SOFA in his living room — in the house he and Peggy built in 1991, on the property they paid off over time — he is backlit by the haze of a late-summer late morning. He likes it here because of his proximity to working ranches, which he frequently visits to experience firsthand the scenes he’ll later translate to canvas.

Although he’s largely self-taught, Bill did study under Michael Lynch and Ned Jacob, both of whom told him to paint from life. He also took a workshop hosted by James Reynolds at the fledgling Scottsdale Artists’ School in 1983.

“Jim was the best Western painter in the country, bar none,” Bill says. “What struck me was that he was no-nonsense and was extremely passionate and was just fearless with a brush, and those things just imprinted on me.”

But one piece of advice Bill received from Earl Carpenter, another early mentor, stuck with him, and it’s something he’s carried with him throughout his career of more than 40 years.

“[Carpenter] told me to leave the camera at home and go get myself an outdoor easel and start painting on the spot,” he remembers. “Start going outside. So, I scraped up a couple hundred dollars and went out and got myself a French easel and went outside — and just got into dreadful messes all the time.”

He is as humble as he is practical. And, Peggy says, he’s pretty stubborn, too.

At 68, he wears the depth of his experiences on his face and hands, and he has a habit of turning his head to the side and looking away as he speaks. He asks if it bothers me, but it doesn’t. He is contemplative and reflective, a trait that tracks, given the way he works and his deep personal faith. Sometimes, he listens to sermons as he paints. Sometimes, he listens to talk radio. Sometimes, there is silence. Always, he says, the process is “a war.”

We have talked about our experiences with fire in the environment that informs and inspires our work. We have talked about children. Mine are 16 and 14. His are grown — one lives in Berlin, the other in California — and Bill is proud of the time he was able to spend with them when they were younger. He softens when he talks about how Peggy homeschooled them before they went to school in Prescott, and how their house was a gathering place for all of the kids’ friends.

We move to the studio. It’s a broad, light-filled room above the garage, with a leather couch, a leather chair and a coffee table covered in magazines. Bill chooses to sit in a rolling office chair. He seems at ease in this space, where rows of art books line the shelves. A boombox. A drawing that his son, Will, made when he was young. Countless studies of horses. Haunches. Heads. Movement. Stillness. On the easel is a work in progress: a cowboy on the back of a gray horse, moving a cow down a hill against a background of deep blue sky and mesas. It is a portrait, a moment, a story.

Artist and special effects specialist Randal Dutra has known Bill for 27 years.

“When you stop to think that Bill is integrating figures, animals and landscape in his compositions, he’s hitting the ‘big three,’ ” he says. “Any one of those is a lifelong study. Yet Bill can do it. And he’s one hell of a seascape painter, too. He’s one of the sharpest eyes I know, coupled with a wonderful color sense of playing warm against cool. If something isn’t right, he’s merciless about correcting it. He is his own toughest critic, and never satisfied — won’t rest until it’s remedied. Bill has scraped or wiped out areas in a painting that others would have been thrilled to have captured.

“His modesty notwithstanding, Bill has an undeniable, burning tenacity for what is genuine.”

That’s a characteristic that Bill will own up to. He struggles with the business of art, with what he calls the “art star mentality.” He’s wary of the concept of generative artificial intelligence, and he bemoans artists whose self-promotion via social media distracts from the art itself. And he takes issue with the notion that everything an artist creates is inherently “good.”

“If you’re not making a lot of mistakes and screwing up a lot of things, and trying different things and throwing them out and scraping them back, and having a lot of things that the public never sees,” he says, “you’re probably not particularly interested in what you’re doing. You’re just doing a product for a paycheck.”

Despite a wildly successful one-man show at Scottsdale’s Legacy Gallery in March 2019 — for which he completed 22 paintings in less than a year — he admits that recently, he’s been compelled to drop out of some of the biggest shows in the country, in large part because he’s unmoved by the demands of the timelines and deadlines of others.

He’s earned that.

We move again, from the studio back to the house, where Peggy has prepared lunch — a Southwestern quiche, pasta salad, chips and salsa. We don’t know it yet, but the fire near Kirkland has been contained. Regardless, Bill has relaxed more as we’ve talked about Arizona and life and the commonalities we find in our stories. Earlier, we talked about legacy. Bill doesn’t think much about it.

“I know where I came from, and I know who taught me, and I know how unable I am to clean the brushes of the people I respect,” he says. “I’ve talked people out of buying my paintings. I’m just weird.”

I challenge him about being a bad businessman.

“Actually, I’m not,” he replies. “I just really like it when what I do gets through to people who aren’t necessarily into the West at all.”

For more information about Bill Anton and his work, visit billantonstudio.com.