“We wanted to stay away from towns and cities and to trace the paths of Ancestral Puebloans and pioneers and prospectors. We wanted to walk 800 miles back into a different time and dimension.”

— Troy Gillenwater

Gil is hard-driving, with a knack for showmanship. Troy is quieter, stealthier. But they’re inseparable, like the Mittens in Monument Valley, and in the four decades since their great adventure, they’ve explored the world. They’ve also given back to it. Gil directs the Rancho Feliz Charitable Foundation, a binational nonprofit that builds homes and provides scholarships through service work and “reciprocal giving.” Troy’s recent goodwill includes an effort to safeguard the future of the Museum of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff. He accomplished that by selling the MNA’s investment land — not to a developer, but into a conservation trust. Both men say their trek across the state laid the groundwork for who they are today: exceptional men who do exceptional things.

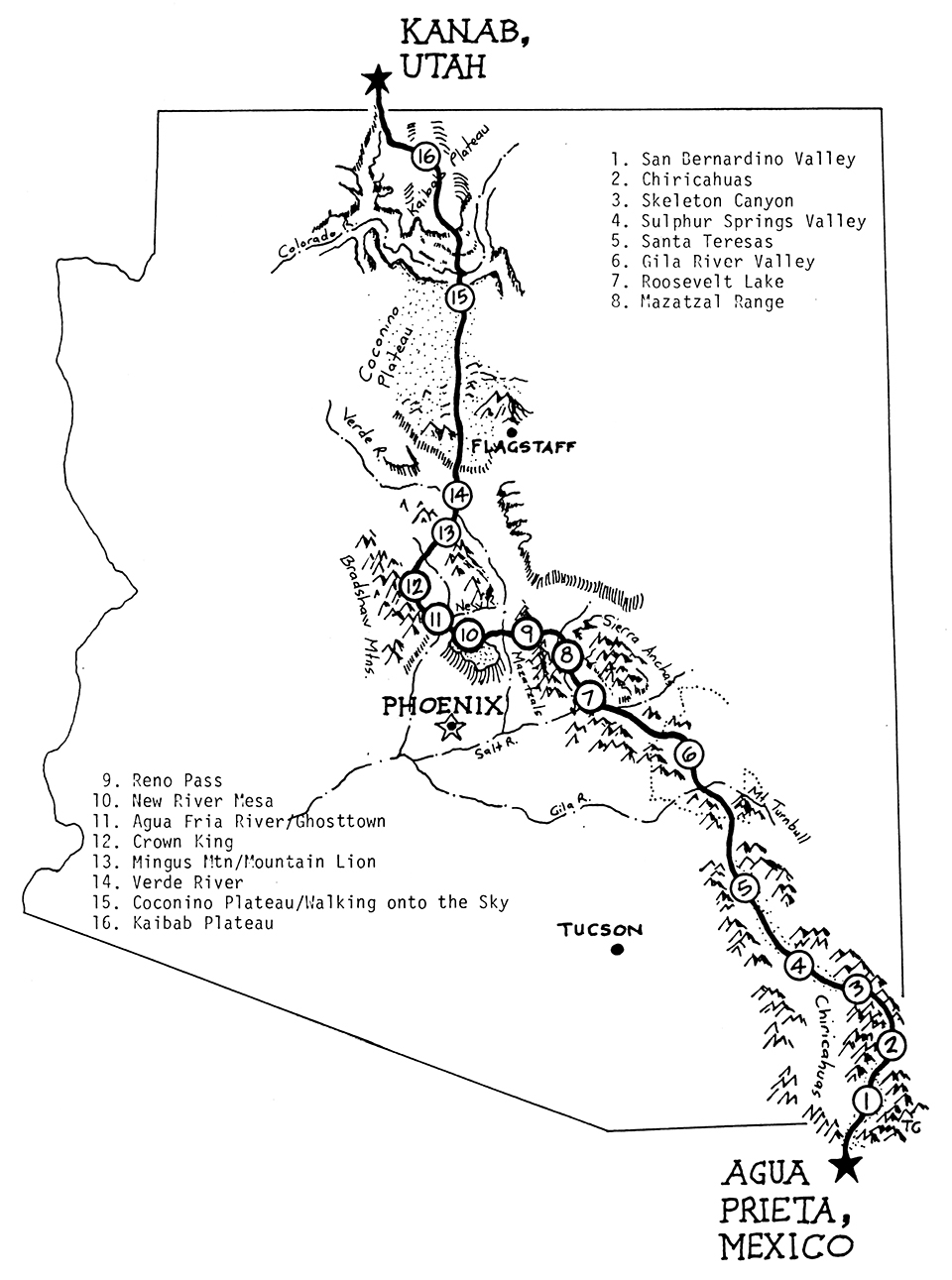

Arizona isn’t easy. Traveling either north or south, explorers encounter a total elevation gain of approximately 100,000 feet in 800-plus miles. But the payoff is substantial: The terrain is visually dramatic, from desert basins to high-alpine mountains, with a trip to the bottom of the Grand Canyon in between. Desert, grassland, forest, tundra … crossing the state is the biological equivalent of driving from Mexico to Canada. Arizona has all the feels. And Arizona dictates how you walk it.

Thus, there was topographical logic to the Gillenwaters’ route. They wanted to avoid the brutal challenges of the Mojave Desert, so they started in the southeast corner of the state. The goal was to stay below the Mogollon Rim in winter, navigate the central part of the state in the spring, take the South Kaibab Trail down to the Colorado River, climb the North Kaibab Trail to the North Rim, and cross the Kaibab Plateau into Utah. In between, they’d make a rest stop in the Bradshaw Mountains to visit a friend, an old prospector named Curly. On their map, they also noted points of historical significance, such as the Dragoon Mountains, Skeleton Canyon and Apache Pass — places that sparked their imaginations as well as their senses. Places where they could walk in the footsteps of some of the original characters of the Old West: Bill Williams, Johnny Ringo, Billy the Kid, Pancho Villa, Cochise, Geronimo.

When it was finally plotted, their route was a patchwork of abandoned roads, open plains, ancestral paths, wildlife corridors and foot trails in and out of Arizona’s wilderness areas and national forests. Bushwhacking would be the common denominator.

Planning the trip took two years, and in that time, the brothers quickly realized they couldn’t carry enough water to be untethered from civilization. “We knew that to backpack across the state,” Troy wrote in the journal he kept, “we would be walking on the end of a leash. We would have to stay close to water, and to stay close to water in Arizona means staying close to people.”

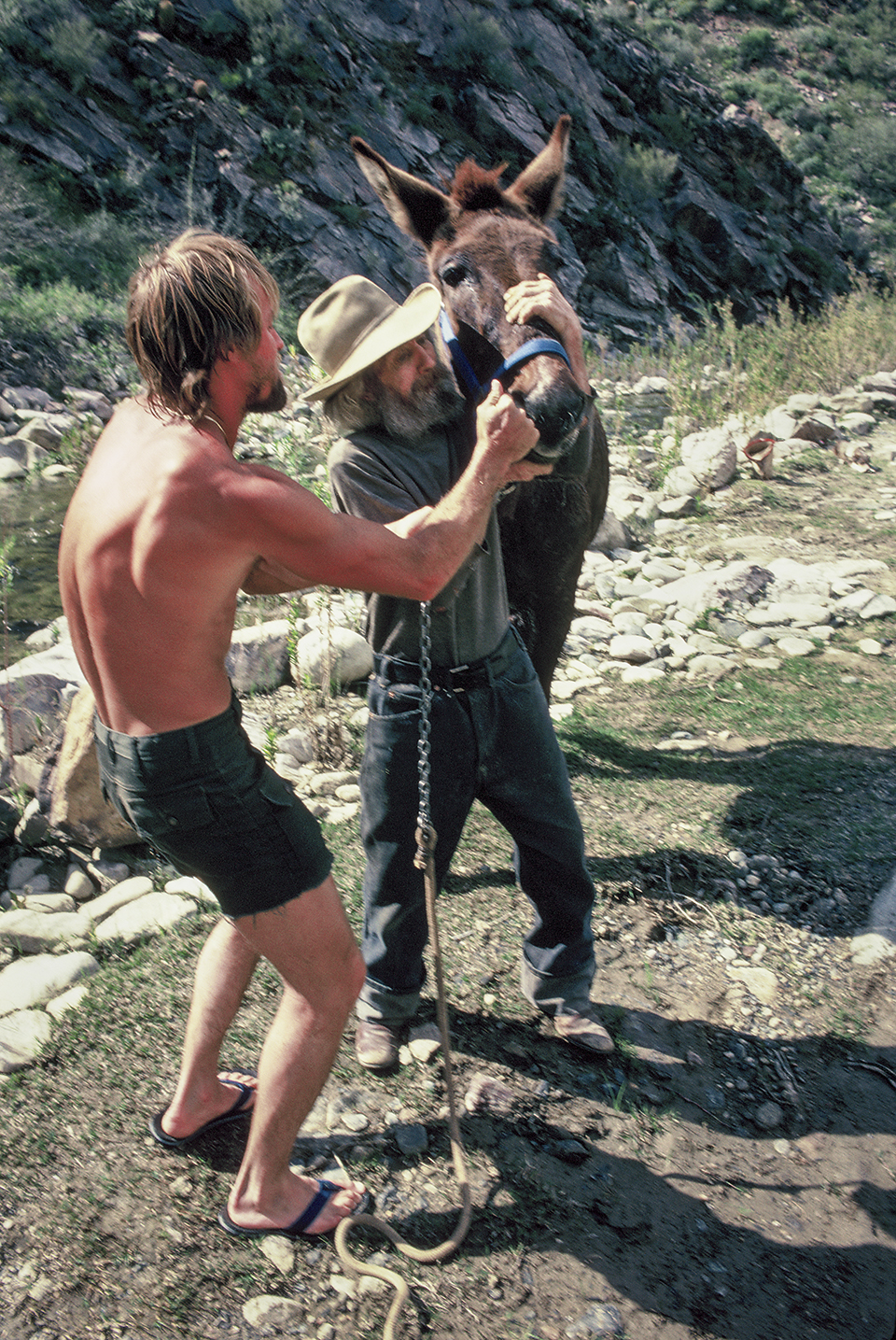

Gil suggested mules. “They could pack all our water,” he says. “And then we could go anywhere we wanted.” And so, Grandma, an agreeable mule, and Judy, who was not, joined the team, even though neither of the boys had any experience with pack animals. “We didn’t know a darn thing about mules,” Gil says. “Seriously, we didn’t know how to take care of a dog, much less these 900-pound animals.”

What they didn’t know didn’t deter them. And on February 28, 1982, they headed north from the U.S.-Mexico border at Guadalupe Canyon, a passage traveled for centuries by nomadic peoples, renegades and human smugglers.

“Our departure was dramatic. We had our ‘Border to Border’ flags flying. We had so much confidence that I half-believed Utah was just on the other side of that hill. I learned two things quick: Utah is so goddamn far away that it is beyond comprehension, and mules aren’t trouble-free. Two hundred yards up the creek, our pack saddles toppled and we began our introduction into mule skinning.”

— Troy Gillenwater

The initial stretch through the lowlands of the Chihuahuan Desert was punishing. The blond grass concealed rocks that made men and mules stumble. “That San Bernardino Valley … all catclaw,” Gil says.

“All catclaw without a trail,” Troy adds. “The dead grass was waist high, so you couldn’t see what you were stepping on … rolling your ankles on.”

“It’s all volcanic,” Gil says. “Volcanic stone. I remember when we finally came over the pass between the San Bernardino Valley and San Simon, looking out at the San Simon Valley, it reminded me of cattle bones. It was bleached, burnt. And I thought, I’m going to spend two weeks in that?”

In 1982, GPS wasn’t available to civilians. So, the boys had to rely on the fine art of map reading. What they didn’t realize was that their topo maps had 80-foot contours, meaning each line represented big stretches of up and down — steep ridges and deep arroyos. Early on, they made the mistake of checking their progress against a gas station map. “We’d been scattered all over,” Gil says. “We couldn’t even get off the Mexican border.”

It was demoralizing. Only 768 miles to go.

“We knew we were in over our heads,” Troy says. “One thing that eluded us in the calculus we used to plan this route was the fences. It really caught me by surprise.”

Fences made it impossible to hit their goal of 14 miles a day. Seeing no other choice, they ended up cutting — and then repairing — a few barbed-wire fences. In cattle country, that’s a cardinal sin. From that point on, the Gillenwater brothers were outlaws. But it was another incident — watering Grandma and Judy at a stock tank — that drew gunfire.

“If a rifleman’s aim is reasonably close,” Gil wrote in his journal, “you will hear the bullet smack the water first, followed by the sound of gunshot.”

“If you boys would have run,” said the rancher, old and bent like a worn-out saddle, “I wouldn’t have been aiming at the water. This is my land. What are you doing on it?”

They told him about their plan to hike the length of the state. He laughed and said: “And you think this country here is open range? Boys, I’m afraid you’re about a hundred years too late. We lose a lot of cattle around here, and we don’t know what you’re up to. You’d better get out of this valley.”

They didn’t look back as they made their way to the Chiricahua Mountains, which presented new challenges because of high winds and freezing cold. Even though they had first-generation Gore-Tex rain gear, their overall outfits were basic: Levi’s and jean jackets. On their feet they wore Nikes, which wore holes in their skin. When the blisters became unbearable, they switched to flip-flops — “intrepid” is in their DNA.

There were other challenges. Most mornings, they’d start the day by rounding up the mules, who would escape from their tethers in the night. Then, on a steep trail that cuts through Horseshoe Pass, Grandma rolled snout over stern. Troy, all 150 pounds of him, tried to hang on to her, but she flipped him over her back, then spun toward him and tumbled down the incline, pack saddles and all.

“When that happens,” Troy says, “it’s pandemonium. You’re worried to death that the animal has broken a leg or something.”

That would have ended the journey. Fortunately, Grandma stood up and shook it off. Nevertheless, things weren’t going well. The mules were hungry — the plan was to supplement the feed they’d packed with fresh grass, but none was growing — and their ribs were showing. What’s more, the mules started bleeding through their noses, and the nearest vet was still days away, in Willcox. Fortunately, a rancher named “Tiny” Hurtado let the brothers rest their animals in his barn in exchange for help with a roundup. Just like that, the Gillenwaters were cowpunchers.

The ranch hands saw the boys as city slickers — and were convinced of that when a calf kicked Gil in the groin and put him down. The cowboys howled. “We were in after that,” Troy says.

From the Hurtado Ranch, they headed north and picked up a hitchhiker, a determined cattle dog they named Little Boogie — they kept telling her to “boogie on,” but she wouldn’t leave. She proved her worth one night on the west slope of the Santa Teresa Mountains. After hours of incessant barking, the boys woke up to find mountain lion tracks circling the area where the mules were tied.

to get the deworming medicine down the mules’ throats,” Gil recalls. “Curley did it in seven seconds.”

Living is what I have done for the past four weeks. I mean really living. When the sky has fallen at the base of the Santa Teresas and the rain is freezing, and mud is sticking to your shoes, your hands … though it may be unpleasant, this is when you’re really living.”

— Troy Gillenwater

The grand plan included food drops in five places: Bonita, Punkin Center, Crown King, Williams and the South Rim of the Grand Canyon. As they’d approach those places, the boys would dress the part of mountain men, wearing their custom deerskin and javelina fur vests. Troy had a small rodent skull tied to a bandanna around his head. Gil wore a coonskin cap. To the unsuspecting passersby, they looked like apparitions from another time. It was an aura the Gillenwaters embraced. In Globe, a reporter for The Arizona Republic saw them and made a photo. After it was published, the aura grew — their story was out, and people were intrigued.

Back on the trail, the Four Peaks became a beacon. The boys were making good progress in what had been a wet winter. But swollen creeks and flooding dams added more obstacles. As they were navigating those barriers, the mules stepped in a “river hole” — a deep pocket in the riverbed — and briefly disappeared beneath the surface. Fortunately, the watertight fiberglass panniers served a dual purpose.

“They acted like water wings,” Troy says. “All of a sudden, our mules were floating down Tonto Creek.”

Horseshoe Dam, which was overflowing, was another difficulty, but a local rancher showed them a sheep crossing under the wall of water. Otherwise, they would have been stalled there for weeks until the waters receded. Instead, they continued northwest toward the Bradshaw Mountains, a place that felt like home.

To get there, they veered 60 miles west of where the modern-day Arizona Trail runs north from the Mazatzal Mountains. The reason was Curly McKibbey, a hard-rock miner Troy had met a few years earlier.

As a teenager, the younger Gillenwater would pore over topo maps, looking for ghost towns and mining camps. At one point, he found two camps on the same creek and figured there might be something interesting between them. So, his father dropped him off outside of Lake Pleasant with a backpack and a father’s well wishes. Eventually, Troy came face to face with a pistol-wielding, hard-of-hearing miner. It was a standoff straight out of a Hollywood movie. The tension was high, but with his gentle demeanor, Troy quickly put the old man at ease and eventually became his friend — a friend Troy describes as a “lonely, desert-wise prospector, river man, hard-rock man and mule skinner.”

Since the 1950s, Curly had been panning for gold and trading flakes and nuggets for groceries in Rock Springs. “He was my living link to everybody I dreamed about in frontier Arizona,” Troy says.

“He was a relic,” Gil adds. “He had one finger missing because a rock fell on it and he had to amputate his own finger. This guy was the real deal.”

Of course, Curly’s cabin was handmade, an off-the-grid fortress constructed from stacked stones and cactus ribs. It was lit by kerosene lamps and warmed by a cast iron stove burning mesquite wood. Curly loved salt pork, pinto beans and Sir Walter Raleigh tobacco. “It’s not that I want to be a hermit,” he said. “It’s just that where the gold is, the people aren’t.”

As the boys approached his cabin on their epic journey, they began hearing a transistor radio — the only indication they were trekking in the 20th century. They tossed pebbles onto the tin roof of the cabin to let their friend know he had friendly visitors. When they explained that they’d marched all the way from Mexico, all Curly had to say was, “You want some coffee?”

They said yes and spent two days repairing their gear, bathing in French Creek and resting. They’d need it, because Mother Nature wasn’t going to make things easy. Heading north from the Bradshaws, they’d encounter extreme heat and a gantlet of cholla beds — “jumping” cactuses intent on making trespassers feel regret. To outwit the heat, the boys started traveling after sundown and through the night. But that brought other adversaries, including scorpions, coyotes and tarantulas — which aren’t deadly, but their bites can be extremely painful.

They survived all of those tests and made their way, avoiding ranches, roads and even a lone miner. They weren’t interested in conversation. Their goal all along was to immerse themselves in another time and experience the landscape as the Indigenous peoples had. And in the Bradshaws, they felt they’d finally arrived. They’d gone from outlaws to cattle punchers to miners, and now, they were one with the land.

“Whatever spirit there may have been on Earth, Yavapai Indians had etched that spirit on rock. Gil and I discovered petroglyphs on the banks of Turkey Creek, spattered like water drops on creekside boulders. Figures of man, lizard, snake and bighorn sheep were carved into the solid rock. One hundred years ago? One thousand? Ten thousand? Nobody knows for sure.”

— Troy Gillenwater

The caravan — Gil, Troy, Grandma, Judy and Little Boogie — climbed to the ponderosa pine country of Crown King, an old mining town where gold, silver and copper once ruled the day. When they got there, their closest friends and family were waiting. To mark the reunion, the boys, dressed in their outback regalia, fired off their 20-gauge shotgun. No doubt, the locals, bellied up to the bar, would have looked at the strange arrivals with confusion, thinking perhaps they’d had one too many.

But for the boys, it was a rare night on the town. The band played, beer and whiskey flowed, and everyone was dancing. Even Grandma and Judy ended up in the saloon, which had its most lucrative night ever, with only two casualties: a table and a door. It was a dream night. However, the next day, reality set in: The boys still had a long way to go. So, they bid farewell to their family and friends and hit the proverbial road. Recommitted, or maybe desperate to get to the finish line, they started clocking 20 miles a day.

As they moved around the east side of Mingus Mountain, they caught sight of Humphreys Peak. At 12,633 feet, it’s the highest point in the state. The ancient volcano became their compass, and a beacon of hope — they could finally see they were approaching the final stretch. But first, they needed to stock up. In Jerome, the only grocery store was closed, so they ended up in a gas station, where they bought 88 candy bars. “To this day, I still can’t eat a Hershey’s,” Gil says.

Nevertheless, the chocolate fueled their push through Red Rock Country, onto the Colorado Plateau and over to Williams, the historic small town along Route 66. As they arrived, so did a snowstorm, and the blizzard forced them to seek shelter. In the spirit of the old vagabonds, they set up camp in an empty boxcar. It was a good plan … until the train started moving. They quickly gathered their things, jumped off and marched on through the Kaibab National Forest toward the Grand Canyon. There was nothing to obstruct their view of an endless sky.

“It was like we were on the roof of the world,” Troy says.

When they got to the national park, they ran into yet another set of barriers — by this time, they’d realized that nothing was going to be easy. The same storm that had waylaid them in Williams had also wreaked havoc on the backcountry trails. When the boys told a ranger they were planning on taking the South Kaibab Trail to the river and eventually walking to Utah, he said: “No, you’re not. It’s closed.”

Desperate, they politely asked to speak with the superintendent, who was cajoled into granting them a special-use permit — but Grandma, Judy and Little Boogie wouldn’t be allowed in.

“When we sent the mules home, we left the Old West behind,” Troy says.

A friend collected their trusty mules and a disappointed dog, and gave them state-of-the-art external-frame backpacks and cross-country skis. However, they left the skis behind, because the forecast called for sunny weather. So, they switched to shorts, pulled up their tube socks and headed into Arizona’s basement. They had 112 miles to go.

Skipping the skis was a mistake. As the trailblazers arrived on the North Rim, there was snow. A lot of snow. They’d been told to expect 6 inches. Instead, there was 4 feet. It was impossible to move forward without post-holing into the drifts. Like so many other times on their adventure, they were forced to improvise, adapt and overcome. This time, they decided to sleep until 3 a.m. — the coldest point in the night, when the top layer of snow would be frozen and walkable. The plan worked and got them past Jacob Lake and into the shadows of the Vermilion Cliffs.

They were getting close to the end. And then, after 10 weeks and 810 miles, they were there, looking up at the “Utah Welcomes You” sign outside of Kanab. It was May 3, 1982. Appropriately, Chariots of Fire by Vangelis was the No. 1 song in the United States.

“It was a great feeling to know that we’d walked all that way from Mexico to be there,” Gil says. “But it was sad, too, because we knew our lifestyle was going to change completely.”

For Troy, the journey was a transformation. “If you go off the beaten path,” he says, “you find hidden jewels. It could be people, places, experiences. It set the course of my life.”

Turns out, his words were both figurative and literal. In the decades since, the two brothers have trekked through Ethiopia, Eritrea, South America, the Himalayas, northern India and Bhutan, and they’ve glimpsed the fabled “lost falls” of Tibet. Places, they say, that wouldn’t have been a consideration had they not hiked the length of Arizona.

“None of that would have been possible had we not had confidence in each other,” Gil says. “I could have never done those things by myself. I would have never tried them.”

“I’m going to miss the stars,” Troy wrote in one of his final journal entries. “I really am. The sun, the clouds, waking up cold, waking up in the middle of the night, coyotes yelping, dusk, 4 feet of snow on the Kaibab Plateau, the Coconino Plateau, tired feet, my sweatshirt, hot chocolate, maps, my journal, hawks, damp clothes, dirty hands and, most of all, my varied thoughts.”

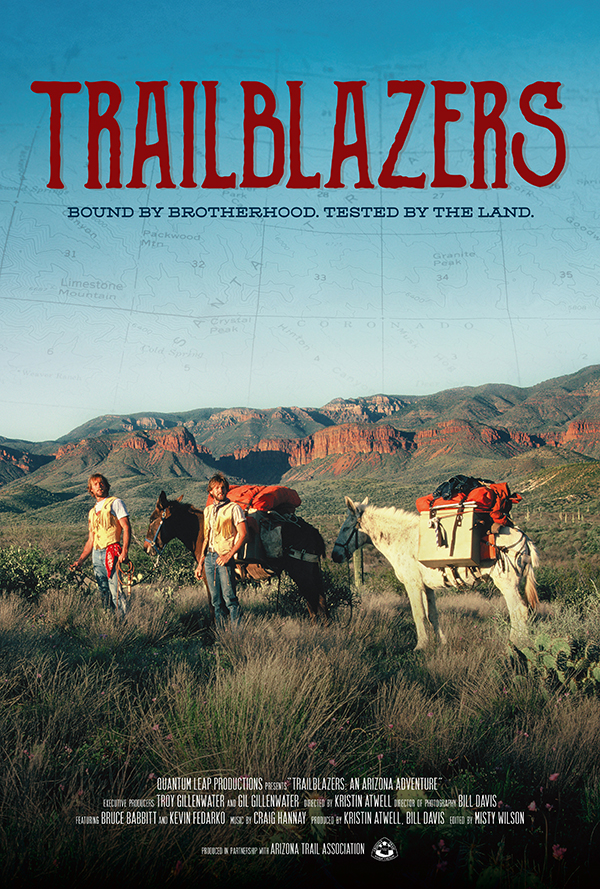

COMING SOON!

In addition to our story about the Gillenwaters’ epic trek across Arizona, look for a new documentary about their journey. Produced by Quantum Leap Productions, Trailblazers will be showing in Phoenix, Tucson and Flagstaff this spring. For more information, please visit arizonahighways.com and follow our social media channels. You can also get updates from the Arizona Trail Association: aztrail.org.

ARIZONA TRAIL ASSOCIATION

The Arizona Trail runs for approximately 800 miles, from the U.S.–Mexico border to Utah. But it’s more than just a trail — it’s a journey through some of the most awe-inspiring landscapes in the West.

The trail is the brainchild of the late Dale Shewalter, a Flagstaff schoolteacher who envisioned an epic route on par with the Appalachian Trail, the Pacific Crest Trail and other classics. He first considered the idea of an “Arizona Trail” in the 1970s. Then, in 1985, he made a trek from one end of the state to the other to assess the possibilities. A through-route was doable, he figured, and the work began.

A decade later, in 1995, the Arizona Trail Association was incorporated as a nonprofit to be an organized voice for the trail. Its mission is to protect, maintain, enhance, promote and sustain the Arizona Trail as a unique encounter with the natural environment. “Perhaps the most important piece of that for me is the unique encounter,” says Matthew Nelson, the association’s executive director. “We work to preserve a pathway for those unique experiences — whether you want to set a speed record on a mountain bike and do all 800 miles in a week, or hike a little bit every weekend and take 10 years to complete the entire trail. Our organization is focused on protecting this resource so that you can interact with nature in a way that is unique to you.”

Because 87 percent of the Arizona Trail is on public land, protection is an ongoing challenge. The threat became palpable last year, when an estimated 1.2 million acres of Bureau of Land Management and U.S. Forest Service land in Arizona was at risk of being sold to private investors. Public opposition helped erase that threat for the time being, but the ATA is always preparing for other threats. In the meantime, the Arizona Trail ranks as one of only 11 National Scenic Trails in the United States. For more information, visit aztrail.org.