On the day before the winter solstice, I follow Jon Hardes up a scree-covered trail at Petrified Forest National Park. I’ve come to see a petroglyph known to interact with the sun this time of year, and I’m hoping to arrive at just the right time. “This [petroglyph] is really unique,” says Hardes, the park’s lead archaeologist. “It’s also in a pretty incredible setting.”

At what looks like a jumble of boulders, we locate a discreet entrance to a shelter created by enormous rock slabs. “We don’t have the right geology to have a lot of true caves,” Hardes says. “But sometimes, you’ll get these really advantageous boulder arrangements.”

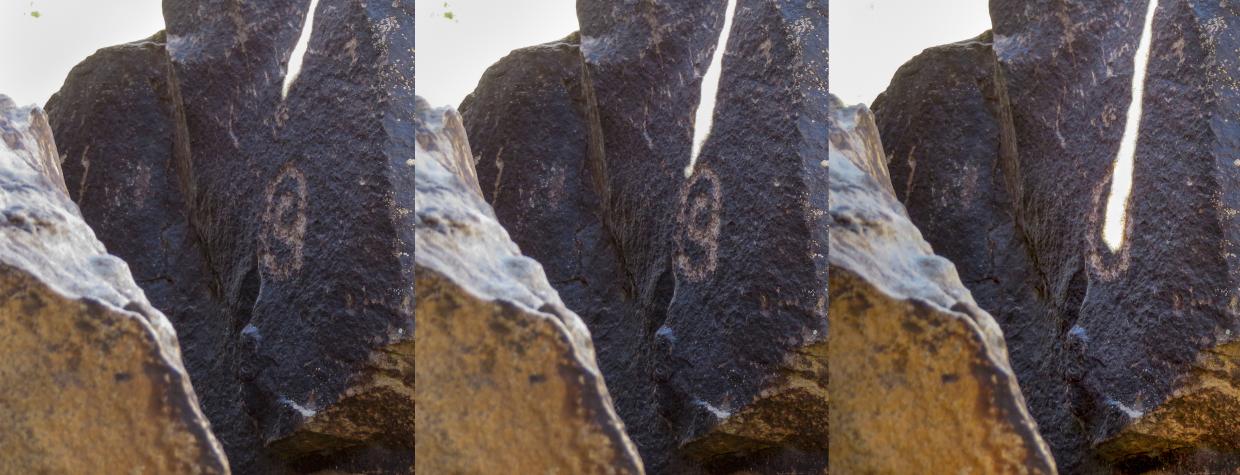

Inside, the space soars above our heads and we crane our necks to examine a large spiral surrounded by a pair of feet in each of the cardinal directions. “That thing amazes me,” Hardes says. “It looks like it was made yesterday.” Then, we notice the wedge of sunlight brushing one of the feet. Not quite believing my eyes, I ask, “Is this it?” In a few minutes, the light has disappeared.

We compare the image I’ve captured on my phone to a published photo made during a past winter solstice. They match. I can hardly believe our timing — if I’d come at any other time, Hardes says, I would wonder how light could ever get in.

It’s well documented that prehistoric cultures around the world have marked the solstices at Stonehenge and other sites. But until relatively recently, archaeologists didn’t know the ancient Pueblo peoples did so using carefully placed petroglyphs. These “solar interactions” have been intensively studied at Petrified Forest, and one of the easiest to see happens during the summer solstice at Puerco Pueblo.

On one such solstice, in the summer of 1977, artist Anna Sofaer watched a narrow band of light move through the center of a spiral petroglyph at New Mexico’s Chaco Canyon, then published her observations in the journal Science. Among those who read the paper were Bob and Ann Preston, who later stopped at Petrified Forest National Park on their way to Albuquerque. Studying the petroglyphs at Newspaper Rock, Ann, a sculptor and painter, wondered if a spiral there exhibited something similar. “That was the long road down,” she says.

“In Albuquerque, we quickly bought a Brunton compass and clinometer and went back to Petrified Forest,” says Bob, an astronomer at the NASA/Caltech Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “And we got stuck there for years.”

The National Park Service provided the couple a home at the park for three or four years, with Ann spending a lot of time there and Bob joining her when he could. They set out to find every rock image with a spiral or circle to see if any of them demonstrated a similar interaction. Ultimately, they documented more than three dozen such interactions at 17 sites in or near the park, mostly on spirals or circles. Most of the petroglyph interactions they identified marked one or both solstices; some observed the equinoxes, and a few marked multiple events. In one special “cave” alone, they documented 13 interactions. To this day, Ann says, “I don’t know of any other place like that.”

The Prestons took a hiatus from their work in the 1980s but later returned to their fascination. “There was a puzzle that related to astronomy and art, our two fields,” Bob says. “And it’s tough to put down a puzzle until it’s solved.” Through 1996, they’d studied 46 prehistoric sites in Arizona, New Mexico and Utah, and documented 109 interactions; they’ve since studied and documented many more such places. The purpose of solar calendars — and petroglyphs, for that matter — is a matter of speculation, but the Prestons’ analyses convinced them that the practice was widespread and intentional.

Many of Petrified Forest’s calendar sites are closed or not easily accessible to the public, but the one at Puerco Pueblo can be seen from a formal trail and viewing area. It’s also among the largest of the roughly 1,400 archaeological sites in the park. With a nearly 360-degree view, the pueblo was close enough to the Puerco River to support agriculture, while closer seeps and springs provided clean drinking water. As many as 200 people lived there at its peak.

They were flourishing, Hardes says, based on evidence of specialization and an abundance of artifacts we’d call art, including pendants and beads. “The ceramics are absolutely mind-blowing,” he says, and that suggests villagers had the time and freedom to become artisans and engage in regional trade.

“That’s going to go hand in hand with [large-scale] agriculture,” Hardes adds, and that endeavor may tie in to the solstice markers. In contemporary Pueblo cultures, the growing season is tied to a lifestyle, with fall ceremonies and hunting ceremonies interwoven and sometimes dictated by the time of year. “So, there were many reasons to track that,” he says.

On this winter day, the small spiral tucked between boulders at Puerco Pueblo is shaded and hard to see. But around 9 a.m. for two weeks surrounding the summer solstice, a shaft of light highlights it, penetrating the center. There’s an interpretive display on the trail, and a ranger will be on hand June 20 to 22, between 8:30 and 9:30 a.m., to answer questions.