The first picture of Grand Canyon I saw as a small boy was a photographic card inserted into our family stereopticon. It evoked from me the clamor of every boy for the Big Adventure of those days: a mule trip down into the Canyon.

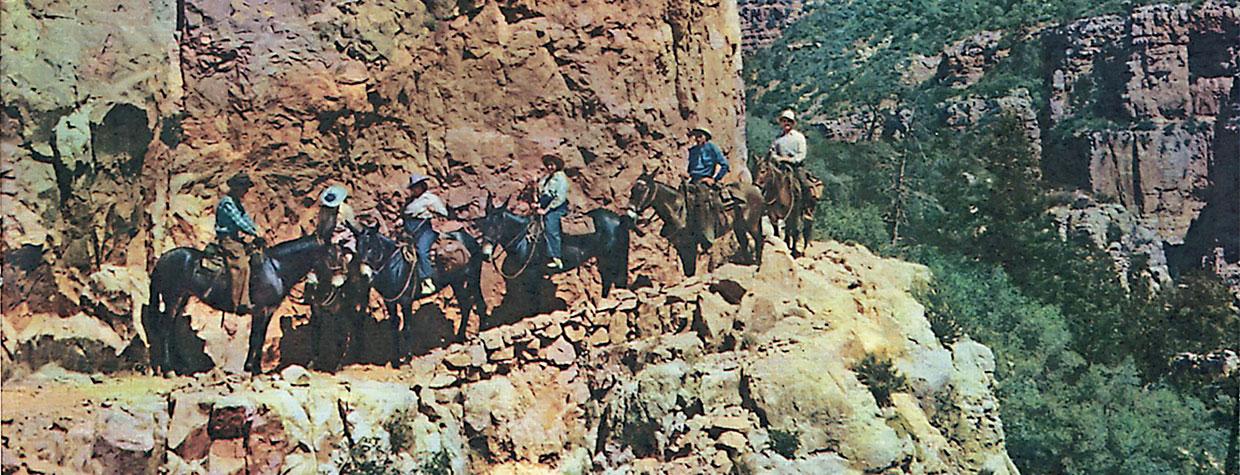

So, of course, we went, riding the spur train to the South Rim and looking down from Fred Harvey’s new hotel, El Tovar. Mother in long skirts and big hat, holding her parasol in one hand and little sister by the other. Papa in riding boots, and the mule driver boosting me up on the back of a scrawny mule. Then down we plodded on a narrow, twisting trail.

The greatest chasm in our global Earth then seemed to me more than I could comprehend. It still does, after so many years of trying to plumb its sublime expanse. Grand Canyon has never been adequately described. It never will be. We can be wary of the wordy rhapsodies written by so many observers.

My view back in Colorado, where I lived, had been of lofty Pikes Peak and the Front Range of the Rockies. Down here in Arizona, I now can practically see it again — but upside down: an immense intaglio instead of a cameo, 277 miles long, up to

18 miles wide, and a mile deep. In it rise high peaks, flat-topped mesas, squat buttes and wide plateaus. There emerge in the shifting light other archetypal forms named Cheops Pyramid, Wotans Throne, King Arthur Castle, and temples for Buddha and Brahma, Zoroaster and Confucius, Apollo and Jupiter, and the sanctuary of the Holy Grail.

It often seems as if Grand Canyon is an immense house of worship itself, dedicated to every faith and myth-drama spawned in the world — a vast universal recollection of all mankind’s architectural and religious heritage.

You may not distinguish the varied forms at sunset when color floods and dissolves their sharp outlines. The hues are royal purples, angry reds, shrieking yellows, cool greens and soothing blues, all enacting their own drama. During this magic hour when the cliff swallows are skittering below my own perch on rimrock, the Canyon seems unreal. A realm of the fantastic unreal, the nonexistent material world of the senses defined by the ancient Sanskrit word Maya — the world of illusion.

The Canyon shows its hard-rock reality on a muleback ride down through a vertical slice in its mile-deep walls. Yet even then it suggests another element of its unfathomable mystery.

At the bottom, where the river is still patiently gnawing at the foot of the sheer walls, one can experience the Canyon’s impalpable fourth dimension. Here its depth translates into time. The compressed, twisted and folded layers of its rock walls, seen in profile, reveal the great geologic eras and ages of the Earth measured in hundreds of millions of years. From the Cenozoic or Modern Era on top — with its brief million-year Age of Man — we read down through the periods of reptiles and dinosaurs, fishes, toothed birds, and land plants, to the oldest Archeozoic Era. Here protrudes part of the Earth’s original crust formed before the planet had cooled. An Earth some 2 billion years old, if geology has put its decimal points in the right places.

We can go no further back into the past. Nor can we extrapolate into the future.

There have been schemes to commercialize Grand Canyon, even to flood it, like its neighbor Glen Canyon. To bureaucratic and private-interest promoters nursing similar ideas, I would recommend the advice of the distinguished English author J.B. Priestley: “If I were an American, I should make my remembrance of it the final test of men, art, and policies. ... Every member or officer of the Federal government ought to remind himself, with triumphant pride, that he is on the staff of the Grand Canyon.”

Yet it is not ours alone. It belongs to everyone, of all races and nations, to preserve as a temple of our one common Mother Earth.

Frank Waters, who was a winter resident of Tucson, is considered to be one of the great writers of Western literature. His life’s work includes books of fiction, anthropology, religion, history, biography and philosophy. He wrote this piece for Arizona Highways a few years before his death in 1995.