Editor’s Note: This story was first published by the Arizona Writers Project, a program of the New Deal-era Works Progress Administration. It was reprinted in the December 1940 issue of Arizona Highways.

Today a blizzard. Radio says it is a storm from Alaska. It blows and snows until one cannot tell where earth leaves off and sky begins. Once in a while there is a pause in the grayish-white gusts and I can see the other houses of Lauritzen, sitting tight on their spot of earth. In those lucid glimpses one also sees gusts of snow, some of it from the sky, some picked up from earth, sweeping up the hollows of the hills, rising like cold surf against the faces of the cliffs, around which the ragged underclouds have already wrapped themselves.

Ordinarily one can stand and look out the window, watch nature cut loose and really enjoy herself like that, and enjoy it oneself. Now it is different. There is menace in this grand frolic. Out southward, 60 miles away, on the very rim of the Grand Canyon, is Tuweep. Somewhere between here and Tuweep are two brothers who went in a pickup yesterday to take the mail to the folks down there. They were not prepared for this kind of weather.

Fifty miles on paved highway is nothing much, even in a driving snow like this. Fifty miles on the Tuweep route is something else. There isn’t a living soul on the whole stretch. There is one cabin, 8 miles out from here. It is deserted. Maybe there is fuel there, maybe not. They could rip off the boards and make a fire if they got that far.

One stands and claws one’s belt, imagines the worst. Two men staggering through that stuff out there, exhausted after a few miles, with the cold and the exertion. Two corpses huddled in a drift somewhere. Already the atmosphere is charged with death. There is a heavy gloom about the place, without this storm. A fresh grave up by the hill — now perhaps two more. Three years ago there were six of us brothers. Is it only two now? Two brothers and a son gone in three years. Now two more? It is like a drumming. It is like the faint echo of taps, as I heard them through the hills two weeks ago when we buried Marion. Graves — all I have done in this damned country is dig graves. In this country the worst always happens.

Daylight shows that the pickup has not come in. Neither have the brothers. As I do the chores for myself and the temporary — I hope — widows, I decide there is only one thing to do: get an outfit together and go look for the boys. They are probably all right, but we do not know. That is the trouble with this country: We can never be sure of anything, except that the worst always happens.

The sky is clear now, but the air is bitter cold, with a slight wind from the northwest. If they did not find shelter last night, God help them.

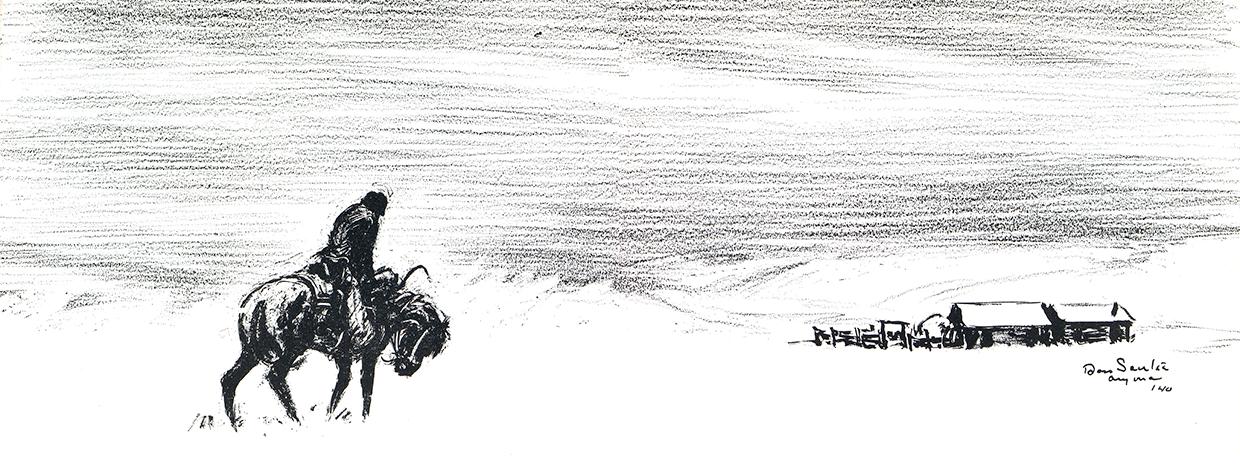

Chores done. While my wife fixes sandwiches, I put on two pair of underclothes, pants, socks, shirts; strap on the knapsack, buckle the overshoes. I should be impervious to everything but gloomy thoughts with that outfit. Both horses are saddled. I ride one, lead the other. If I meet the boys coming in afoot, the three of us can take turns riding back.

Over Berry Knoll we seem to crawl, and ever so slowly down toward the deserted Childers cabin in the lake bottom. Now that we are out of the shelter of the cliffs, the north wind really begins to cut. I must take frequent turns warming one hand in the pockets while the other holds the reins of the two horses. It is so much slower, leading one horse. Both are reluctant to go in a direction away from hay and shed.

There are still jagged clouds over the cliffs and over Pine Valley Mountain in the northwest. It might cloud up and storm again. I urge the horses on, following the faint track the pickup made going toward Tuweep an eternity ago — or was it only two days ago? The snow has drifted high over the track, but there is still enough of it to follow. Here and there we plunge into a wash, completely filled with snow, and it looks for a moment as though we might not be able to flounder out.

Up over the cedar ridge we creep, the horses’ feet sinking far into the soft snow, while I scan the landscape continually, seeing in every greasewood brush and scrub cedar the dark outlines of a man against the white. The wind is increasing now; we seem to be floating slowly over a silvery mist, a mist that has myriad little sharp, cold blades that cut at one’s face and hands.

Now we are finally atop the ridge and going across a flat mesa dotted with scrub cedars. There is a herd of horses pawing at the snow to find grass beneath. It is a comfort to find something alive in that white expanse of quiet death. The horses’ tracks have made deep trails in the snow, and with the light patterings of rabbits’ feet have made black-shaped designs in the smooth surface, like patterns in old lace.

Lady, the white springer-collie, has followed me. She runs about endlessly, plowing through the snow. Now and then she starts a jackrabbit from a bush. Away it skims across the drifts with its light feet, light body, while her heavier body and shorter legs wallow along futilely and frantically after it. She has better luck when she surprises a chipmunk on a foraging expedition. His short legs are not so fast as hers, and she finishes him. There are other evidences of murder in the snow as we go along. There is blood and entrails and rabbit fur scattered over a drift. Tracks and signs of struggle all about. Far across the mesa I glimpse the murderer, a thin, gray line moving across the glittering surface of the earth. A fox, perhaps a coyote. I cannot tell, for the image is blurred in my colored glasses. I remove the glasses, but the object disappears entirely in that blue-white glare. Those glasses, by the way, make an unreal world seem more unreal.

The high wind clouds sweeping up over the Buckskin Mountains in the west look dark, moody, foreboding. The mesa is a crystalline fairyland marked by crystalline shapes, motionless, soundless, of grazing horses, snow-laden cedars, bushes reaching above the snow, icicles like pendant glass prisms weighing their naked twigs. When I take off the glasses, the scene dazzles, still unreal, still gloomy in its blue-white light — far gloomier than darkness in a garden of roses, lilac, delphinium. Fine time to think about gardens!

The sun has crept halfway down the western sky, so I tie one of the horses to a cedar and spur the other into a gallop. We are soon at the southern end of the mesa, where we can look down over the wide Antelope Plain. White, white, everything is white; even old Mount Trumbull, usually deep blue. There is a dark line at the far end of the plain. Clayhole Wash, skirting the valley along its southwestern edge, until it fades out of sight to northward, under the Calico Hills. But now even the Calico Hills are white. Even the volcanic cones, usually black, look like white warts on the white death mask of the earth face below me. Earth not somnolent, earth dead. The stillness is not the stillness of rest, of a simple quiet scene; it is a stillness from which every warm, living thing has been swept and driven, purged.

No life nor movement on that whole wide plain where two men and a car should be. The sun is only an hour high now. Might as well go back, get an early start in the morning with an outfit equipped to go on through till the lost are found.

We come back to where the horse is tied, and I get on it to let the other rest and follow along behind, which it does willingly enough now that we are going in the direction of the shed. Some of the grazing horses follow us for a space, their plunging, galloping hooves throwing up a white mist of snow that is like dust in midsummer, except that it gives off rainbow colors in the light of the lowering sun.

Down over the ridge at a heavy, wallowing trot. The sunlight has gone from the valley now but still glows on the cliffs. They are like palisades of brittle red candy, the kind of candy which hangs on the Christmas tree, with white ridges of artificial snow sifted over them.

Over Berry Knoll finally, and the little spots of yellow light that are in the village begin to appear. I stop at Deputy Sheriff Black’s to arrange for the sled that was used two years ago when we had our bad winter. He says he will fix up the sled and go along with me tomorrow.

Now across the bridge. It seems so much warmer now. Maybe it’s just the light of home. Horses are unsaddled, fed. Feet are in the oven. Thank God for home, fire, wife — and, of course, beans.

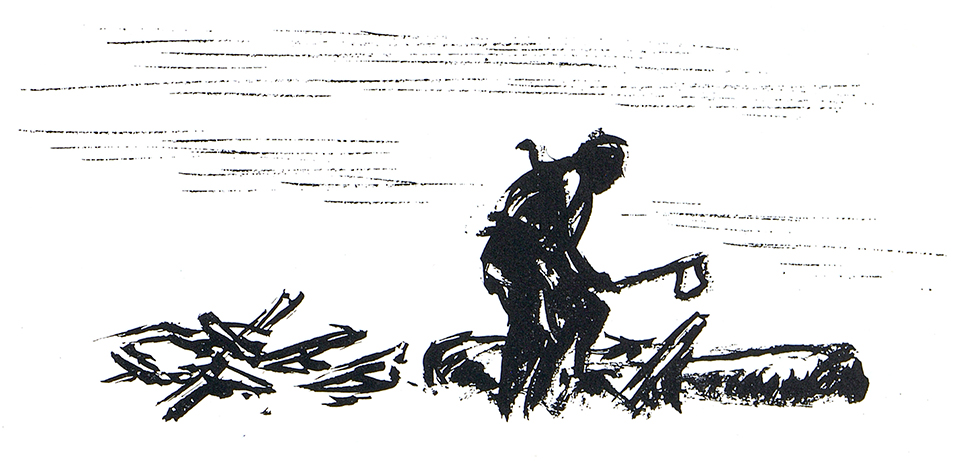

Chores done for everybody in the cold dawn. Things drag when one is in a hurry. Cows won’t give down, calves won’t drive, pigs try to eat your arm off while you clean their troughs, water all frozen up. Finally it is all done, horses harnessed. The sun trickles a cold light over the eastern ledges. It will be clear today and, I hope, warmer.

Across the creek with the team, I have to wait a couple of hours till we get the sled fixed. Wrong tongue, wrong size bolts, runners rotted and caked with clay. Wonder if the minutes make any difference to the boys somewhere “out there.”

Finally we are ready to go. I have brought a grub box, full, plenty of blankets. Deputy Black puts in his. There is baled hay to last us a week. We are prepared to go all the way to Tuweep if necessary, a four- or five-day trip.

We pull away from the quiet village. The morning sun is high when we come down toward the Childers cabin and the old lake bed. The sled is hard pulling. Horses are steaming from the exertion of wading the snow, a job in itself, and that load to drag. They will be done in if we have to go the whole way to Tuweep and back.

Down over Mount Trumbull, it doesn’t look so good. Gray wind clouds begin to hoop their long tentacles across the sky. Radio said storm again. Comforting thought, another blizzard, with our outfit miles from anywhere. Anyway, we’ve got plenty of bedding, plenty of grub. We’ll throw in some wood when we get to Cedar Ridge. The storm can’t do anything to us.

Millard, the deputy, is saying something about “Is that a crow circling over there, or is it a buzzard?”

I have no answer, for I am not looking where he is looking. My eyes have caught sight of two dark, moving, upright lines against the snow about a mile ahead. I begin to get all warm inside, as if it has suddenly come spring. “It’s Dean and Dawn — safe!”

It seems funny, riding along, joking, laughing, telling about two nights in deserted cabins, plowing through drifts till the gas ran out, wading through snow up to their knees, two days on one loaf of bread and a small hunk of bacon. It seems funnier than you think. It is very funny, now that our backs are turned to those darkening wind clouds in the south.

The same home, the same cuddling little daughter, the same wife — and, yes, the same beans — but how different everything is! There is a warm glow over the world that has not been there for two weeks, for months, ever before, in fact.

The feet in the oven are beginning to feel their socks, the beans are revolving contentedly in their intestinal orbits, when a knock sounds on the kitchen door. “Come in.” It flashes through my mind that it is some of the folks come over to congratulate me.

For a moment — one sweet shining moment — I have forgotten that the worst always happens. Three men are looking at me kind of sober and asking me about saddle horses for tomorrow. Dale Finicum, the mail driver on the Short Creek-Fredonia route, is missing. Glen Johnson’s tractor came through from the sawmill on Kaibab this afternoon. Glen inquired about Dale in Fredonia. Nobody knew anything. Glen wanted to find him to learn about the condition of the roads. When Glen got to the mailboxes 15 miles southeast of Short Creek, he found Dale’s truck, fast in a drift, headed Fredonia way, the mailbags he took with him Wednesday locked in the cab. Not a sign of a track around the mail truck. This isn’t like Dale — two days overdue with the mail, and him with a wife here. She had appendicitis pains when he left; he was worried. He ought to be back.

My too-vivid imagination sees him leave his car in that blinding wall of snow and go staggering over the flats, recognizing no landmarks, finally crumpling up in the snow. Mentally I am digging the frozen body out. It is 3 a.m. — might as well get up, slip into my clothes before my skin crystallizes in this frost. Make a fire in the kitchen stove. Put on the coffee, slice off some bacon. While things are warming up, go to the corral and throw some hay to the horses. They are too tired from yesterday to even snort in the darkness. The pitchfork feels frozen to my gloves. I can see the glint of frost on the backs of the cows lying there in the starlight. Their breath comes in white puffs.

There’s another light on the flat. Dawn’s. He soon comes stomping in. His face is still reddish-purple from the Tuweep trip, but he can still grin. He’s had a harder time of it than I have.

There is no light in the village. Nobody worries. But yes, there is a flicker of yellow in Deputy Black’s window. When we knock on his door, we hear a muffled “Come in.” We catch a glimpse through the open door of the long face of the deputy peering out between bedcovers and a stocking nightcap where hair should be but isn’t.

He says something about having to harness up a mule, then he’ll be ready. Might have to have the mule pull Leonard’s car. I impatiently visualize that mule clipping along at 2 miles an hour. We on horses could have found the body, the funeral over, before the car got there.

“I’ll go get Leonard up. Maybe I can roust some other men out to go along and push. Glen’s tractor must have made a pretty good track yesterday. Maybe we can get along without the mule,” I suggest.

At Leonard’s. This time a stocking nightcap pokes itself out the front door. Yes, he’ll be ready in 10 minutes.

Soon Leonard comes out dressed and steps on the starter of the old sedan in front of his place. After a good deal of whining and retching, the starter brings a cough out of the motor, smoke begins to pour from the exhaust. I keep myself warm and contented by carrying water for the radiator from the windmill tank. As fast as I pour in water at the top, it leaks out the bottom. We discover a leak in the bottom of the radiator. The hole is finally plugged with rags, and we are away.

Some of the going is not bad. The tractor has broken track, but where the drifts were heavy the tractor has only packed the snow down, and the hind wheels of the little sedan shake and shiver and burrow down through the powdery snow to the ground beneath. In these spots we have to snag onto the bumper with lasso ropes and pull the car along with ponies while those in the car get out and push.

Only 4 miles out when the sun sends its first frozen shaft over the Cane Beds hills east of us. I finally decide to mount the third horse, a little mustang which is too slow and too lazy to do any pulling, and ride on to Cane Beds, to Glen Johnson’s home; maybe get him to go on to Pipe Spring with the tractor, phone in to Fredonia for any information about Dale. By kicking and lashing the little mustang, I manage to keep ahead of the car until we reach the forks of the road, where I turn toward Cane Beds.

Glen has had a hard three days bucking snow but promises to be out. He tells me of a cutoff south toward the mailboxes where Dale’s car is parked. It will save me 2 or 3 miles.

After what seem hours of wallowing through drifts, we come out at the Perkins ranch. I stop to water the horse. Mrs. Perkins opens the door. They haven’t heard about Dale being lost. I suggest that the Perkins boys saddle up and follow along. There is no very audible response.

Now we are crawling up onto Forty Hills Mesa. Even without their blanket of snow, these hills all look alike. Each one gives the impression that it is the last. I watch the side of the road for any sign of man tracks. Dale could have gone back toward home.

We top the last hill. We should be able to see the mail truck. It is not in sight. It is gone. No cars, no horses in sight. Signs in the snow tell me that the mail truck has been dug out. Far off to westward, I see two black dots moving slowly across the sheet of white. That would be Deputy Black and brother Dawn on the horses, cutting across country to get the mail out of the stranded Tuweep truck, or to Marshall’s to help him resurrect the county tractor. All must be well. The search is over. Over a ridge Fredonia way comes Leonard’s car, followed by the mail truck. I wait while they stop every so often to dig themselves out of drifts. I go to meet them. Dale is there, shovel in hand. It is like the resurrection. I put my arm around his shoulders. He is too busy to realize that for 16 hours we have been finding him dead behind every bush on the flat. All the time he has been at Marshall’s, trying to help get the county tractor to whisper sweet messages long since forgotten.

Over the Forty Hills I see Glen with his tractor, and several horsemen who have met the mail truck and turned back toward home. It makes one feel a little foolish — all this stir for nothing. I doze while the horse pokes along, now and then raising my eyes to the cliffs, which never seem to get any nearer. They stand out, red and blushing but brave above the gray-white plain — like an intelligent thought in a newspaper.

Why do you live in this country? It is mean, miserly, brutal — but sometimes it smiles and is kind and you love it. Maybe you are just stubborn. There seems to be a conspiracy between man and nature to keep you from being here, living here. But sometimes you love even that.