As the sun rises over Tempe Town Lake, a goldendoodle pulls a woman wearing spandex along the paved riverwalk, past a flock of tethered swan boats. From the other direction, three college-age men on electric scooters scatter a flock of grackles as they glide past a middle-age man in a neon shirt, doing pushups against a bench.

It’s a scene you might expect at a modern park in a college town. But the people who built the park a century ago would hardly recognize it. Over its long history, Tempe Beach Park has evolved to reflect the fashions and passions of the times. It has included a skating rink, a bowling alley, tennis courts and, in 1934, an outdoor movie theater. Boxing was big in the ’40s, softball in the ’50s, and love-ins and draft protests in the ’60s.

Through those decades, the one constant was the swimming pool. The state’s first Olympic-size pool was the reason the park was created, and it quickly became a regional attraction, hosting Arizona’s first national competition in any sport. It also was where generations of kids learned to swim and spent long summer days. Those days loom large in the memories of those who came of age riding their bikes to Tempe Beach before stopping at the Laird family’s Mill Avenue pharmacy on the ride home for a 5-cent root beer in a frosted mug.

“It was a Charlie Brown world … an adult-free zone,” writes Sally Cole in her collective memoir Alligators in the Baby Pool: Remembering Tempe Beach. “The sun beat down on the city’s children, the water shimmered, [and] the jukebox played its endless tunes, punctuated by the rattle of the diving boards. Those of us who spent our youth there can call up those days from decades hence, can still smell the pool deck under our noses … can still feel the slap of a mis-dive from the high board and that icy plunge.”

Before Tempe Beach, residents swam in the Salt River, at a bend north of Tempe Butte (now also known as Hayden Butte or A Mountain) that the local newspaper described as “a fine bathing pool” with “a stretch of sand … surpassing many of the ocean beaches.” There, locals installed a diving board and talked of building a bathhouse.

But swimming in the river had its hazards, including broken bottles, tin cans, and risk of infectious diseases and drowning. The Tempe Civic Club, which later became the Chamber of Commerce, proposed a public pool as a safer alternative and a place where the city could host swimming and diving competitions.

The club’s preferred site was at First Street and Mill Avenue, where years earlier Charles Hayden had cultivated a garden, planting grape vines, fruit trees and stands of white oak and black walnut. The property’s owner at the time agreed to sell it, offering a $500 rebate if the new facility bore the name Tempe Beach. The city purchased the land, and the Civic Club sold stock to build the pool.

Tempe Beach opened in July 1923, but local kids didn’t wait for the official opening to swim. William Windes jumped in the pool the first day it held water and continued to swim there nearly every day of every summer until he left Tempe at age 19. In an unpublished memoir, he wrote that he climbed onto the diving platform even before it had stairs so he could be the first to dive off it.

A river-rock building served as a ticket booth, and some boys spent nights on its roof, sleeping on old mattresses and jumping down to cool off in the pool. A couple of discarded structures served as bathhouses; Dr. Reginald Stroud recalled that it “took real courage” to enter them on a hot afternoon.

Stroud brought the first sanctioned swim meet to Tempe Beach in 1925. And in 1932, Tempe beat bids from much larger cities to host the women’s national swimming and diving championships, the first national sports competition held in Arizona.

Kids lined up for free, Red Cross-sponsored swimming lessons, taught assembly-line style to 200 students at a time and culminating with a goldfish swim. While teaching methods evolved, lessons remained a staple for decades.

In 1927, Tempe bought land west of the pool, extending the park to Ash Avenue. The Civic Club’s lease required yearly improvements, and that year, it built a river-rock bandstand near the pool. It also continuously expanded the picnic area toward the river, planting grass and cottonwood trees.

And after a committee member refused to vote on any issue until a new bathhouse was approved, the club commissioned one. Billed as the largest and best equipped in the Southwest when it opened in 1933, the river-rock structure at Mill and First kicked off an era of steady development with the help of the Works Progress Administration.

Subsequent projects included croquet, horseshoes and shuffleboard, along with a three-lane bowling alley, a roller rink, a regulation tennis court — “the finest court that can be produced” — and a multipurpose court. And newspaper stories in the 1930s mentioned baseball parks, handball courts, volleyball and softball courts, and a rock wall built of river boulders. Teams played football several nights a week. And in 1934, Dwight “Red” Harkins built an open-air movie theater, an ill-conceived project that lasted three months before a monsoon storm ended its run.

Against the roadway leading to the Ash Avenue Bridge, the WPA built cobblestone bleachers, and it also surrounded the park with a cobblestone wall. The tennis courts stayed busy with lessons and tournaments. Boxing debuted in 1940, and by the 1950s, three-round, Golden Gloves-sanctioned boxing cards took place in the old roller rink.

But the biggest draw was softball. After lighting was installed in 1937, men’s, women’s and youth leagues played nightly, and Tempe Beach hosted Western tournament games. Sometime in the 1950s, the multipurpose court was redesigned as a dedicated softball field; in later years, American Legion baseball teams played there, and Ladimir “Ladmo” Kwiatkowski, of The Wallace and Ladmo Show fame, coached peewee, rookie and all-star teams.

In the 1960s, young people packed the park for love-ins. “There was a bunch of them,” recalls Mary Holmes, whose family started coming to the pool in the early ’50s, when she was 3 or 4. “It got to be almost every weekend … and there were always bands playing.” Even after her family moved to Scottsdale, Holmes returned regularly: “I used to go there at night with a group of guys and girls, and we’d climb the trees and just sit in the trees and hang out, because it was nice and cool.”

But by then, cracks were beginning to show in the summer paradise. As early as 1950, the Chamber of Commerce debated ending its sponsorship, citing the expense. Rough spots formed on the bottom of the pool, and the surrounding deck cracked. Antiquated plumbing and electricity in the bathhouse created other issues.

And because it lacked a filtration system, the pool had to be drained and refilled every few days. A former lifeguard recalled there being so much silt in the water by the end of the third day that lifeguards had to dive in with flashlights to search for swimmers before letting the water out.

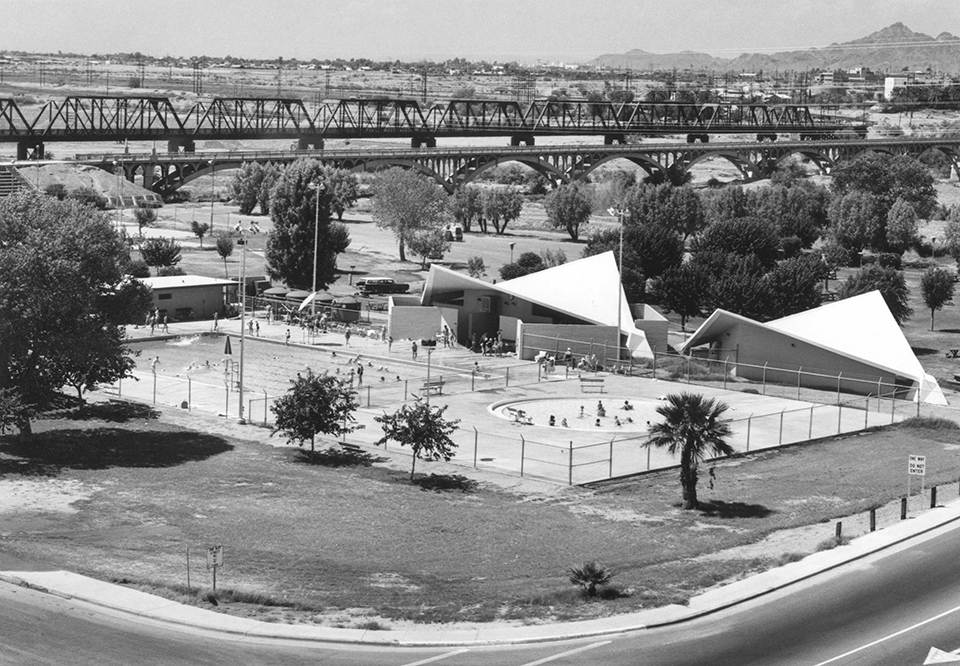

To address those issues, voters approved a bond issue to modernize the park in 1963, but many were dismayed by the results. A modern structure with a soaring roofline replaced the cobblestone bathhouse. The filtration system in the smaller pool required swim caps. Gone were the diving boards, grass and cottonwoods. “It didn’t have the same feeling,” says Tirzah Heywood, who quit the swim team.

One patron told Cole that Tempe Beach wasn’t fun anymore. For Cole, the real loss was the city’s commons, where residents had always gathered for graduations and celebrations. Community members interviewed for a 1999 report recalled the park’s lost natural beauty, lack of rules and unparalleled freedom.

The new pool that was expected to last 25 years, Cole noted, closed after 10. It sat empty for a decade until the Tempe Arts Center adapted the facilities. The pool became an art installation called Terminal Beach and was later filled with sand and gravel for a sculpture garden. In 1998, the pool and its facilities were demolished as Tempe Beach prepared to remake itself again, as part of the new Tempe Town Lake. By then, its primary users were unhoused residents.

Today, a river-rock entrance arch stands where the cobblestone bathhouse once did, and a wide promenade spans the former pool area. Most of the Ash Avenue Bridge was demolished in 1991, but a preserved abutment supports a veterans memorial. The cobblestone bleachers, protected behind chain-link fencing, await renovation.

Tempe Beach Park now attracts new users who rent scooters and kayaks via mobile apps. Little League players use Luis Gonzalez Field, and the city hosts some 40 events at the park each year.

In talking about the proposed reboot in 1999, then-Councilman Joe Spracale sounded both nostalgic and forward-looking. “Tempe Beach was my salvation,” he said of the 11 years he spent as a lifeguard and swim coach. “Everybody was there. It was the social gathering place all summer long.

“We’re going to bring it back. We really are.”