The most famous animal in national park history isn’t a Yellowstone grizzly or some majestic Grand Teton moose. It isn’t a black bear at Yosemite or a shaggy white mountain goat roaming the granite of Glacier. Those animals have their appeal. But none of them ever became an icon like Brighty, the little gray burro who ranged wild and free at the Grand Canyon, from the Colorado River to the North Rim, for more than 30 years.

Brighty’s legend was born a century ago and went on to inspire Marguerite Henry’s classic children’s novel, Brighty of the Grand Canyon, and a 1966 feature film of the same name. Although fondly remembered, with captivating Wesley Dennis illustrations that range from biological precision to Pooh-like whimsy, Henry’s book is no happily-ever-after bedtime story. The author, sweet-voiced and with the gentle mien of a favorite teacher, didn’t spare Brighty from menace.

Mountain lions maul Brighty — twice. His companion, Hezekiah Appleyard, the grizzled prospector known as “Old Timer,” is murdered, and Brighty survives a harrowing plunge into the Colorado’s whitewater. Brighty also goes rogue and battles an alpha burro before bad guy Jake Irons captures him, leading to a siege in a snowbound cabin. There are triggers aplenty — and, like the best of Disney, Brighty is just scary enough to be unputdownable.

For boomers who grew up with the novel during the golden age of Disney documentaries and View-Master projectors — and for millennials and zoomers who logged off for long enough to read the book — Brighty and the Grand Canyon are inseparable. It’s hard, then, to imagine that this beloved survivor once was exiled from the national park he symbolizes.

But the three lives of Brighty — the real, the literary and the cinematic — merged into a narrative that became entangled in a vexing environmental drama encompassing issues we still grapple with today: the preservation of native species, animal rights and, even in a pre-social-media era, the weaponization of emotion to influence policy. Long before “Free Britney,” the “Bring Back Brighty” campaign helped lead to the helicopter airlift of hundreds of Grand Canyon burros that had been sentenced to die.

It’s a complex legacy for a stubborn donkey with a hankering for flapjacks.

Bio of a Burro

For those of us who worked at Sunset magazine, sooner or later, someone would let you in on a bit of company lore: The legend of Brighty began with a 1922 article that ran in the magazine. And with this reveal came whispers that the story contained a dark secret guaranteed to generate nightmares.

Bearing the pre-clickbait headline of Brighty, Free Citizen: How the Sagacious Hermit Donkey of the Grand Cañon Maintained His Liberty for Thirty Years, the article was written by Thomas Heron McKee. Writer of 1918’s The Gun Book for Boys and Men, McKee was no random freelancer who had stumbled on Brighty’s story. He lived at the North Rim, where he and his family operated a Wylie Way camp, a concession with tent cabins, near Bright Angel Point. (William Wallace Wylie, the originator of the camps’ concept, was McKee’s father-in-law.)

Brighty’s story varies depending on the source, but in McKee’s telling, it began with tragedy upon tragedy. At the request of a woman whose husband had disappeared in the Canyon, cowboys John Fuller and Harry MacDonald descended from rim to river to see if they could find him, dead or alive. Their route was little more than a deer path, and during a rainstorm, the cowboys’ horses slipped from the cliff and died.

The herdsmen continued to a spot near the Colorado River, where they found an unoccupied campsite with a gray burro, Brighty, grazing nearby. Rifles and revolvers were stashed inside the tent, and an expensive gold watch dangled from a pole. The occupants, a pair of Chicagoans seen traveling from Flagstaff with two burros, clearly planned to return, probably after restocking on the South Rim. But other than tracks that ended at the river, Fuller and MacDonald found no traces of them and presumed the visitors died crossing the Colorado.

When Fuller returned six months later, Brighty was still there, hanging around. This time, he accompanied Fuller to the rim, and thus began the burro’s annual migration: wintering in the warm depths along Bright Angel Creek before climbing to the high country after the snow melted.

Brighty came and went as he pleased, other than occasionally being pressed into service hauling loads for prospectors — that is, until Brighty invariably managed to free himself. McKee delighted in how Brighty outsmarted his captors. He had a talent for escape and a knack for camouflage, concealing himself until he could rub against a tree to dislodge his loads. When a bell was placed around his neck to track him, McKee wrote, Brighty learned “to move along with a gentle swaying motion of the neck, resembling the swing of a waiter carrying a full cup of coffee, which hardly disturbs the clapper.”

McKee added: “He can be coaxed but not driven, and the limits of the service he renders are set by himself.”

At the Wylie Way, Brighty was more cooperative. He became known for his fastidiousness, never leaving any manure within the camp itself. He allowed younger children to straddle his back “from crupper to ears” before gently brushing them off “in a jolly pile,” McKee wrote.

According to McKee’s son Bob, Brighty was outfitted with a saddlebag that supported two water cans fashioned from Model T gas tanks. Each day, Bob and Brighty made multiple half-mile trips to a spring off Transept Canyon, then climbed the 200 feet back to the rim, with pancakes as Brighty’s reward. A sign appeared on a tree where Brighty patiently stood as the tanks were emptied:

WYLIE WATER WORKS

Power Plant: Brighty

General Manager: Bob

Brighty represented a major upgrade from Ted, his recalcitrant predecessor named for President Theodore Roosevelt. In some tellings, Brighty accompanied Roosevelt and Canyon legend James “Uncle Jim” Owens on a 1913 mountain lion hunt. One photo of the hunting party even identifies Brighty as “the last burro on the right.” But there are doubts about its accuracy, because while Roosevelt later referred to burros Ted and Possum by name, he never talked about Brighty — although Roosevelt did mention that three burros worked the hunt.

Brighty’s role in the building of an early suspension bridge across the Colorado seems more conclusive. A 1921 National Geographic article described Brighty as becoming “the bridge mascot” after he started lingering near the construction site. He even deigned to haul the occasional load, and the article credits Brighty with guiding the bridge foreman across Bright Angel Creek and up to the North Rim. (More dubious Canyon lore claims that Brighty’s wanderings blazed the trail from river to rim.) McKee wrote that when the time came to decide who would first cross the bridge, “by acclamation and by the consent of the authorities, the honor was bestowed upon Brighty as the oldest and most distinguished inhabitant of the place.”

But the story then took a macabre turn: As a coda to

McKee’s article, the editors announced Brighty’s death. He was killed for food by two men snowbound with the burro in a Bar Z Ranch log cabin.

In an unpublished piece from Grand Canyon National Park archives, McKee details these sad final days, based on the account of a World War I veteran trapped with the desperado holding Brighty captive. When Bar Z cowboys found his remains the following spring, they respectfully doffed their hats and solemnly buried him.

McKee concluded, “An old, old friend had departed.”

The Literary Brighty

Marguerite Henry had already written 22 chapters of her Album of Horses when she decided it needed a 23rd.

Despite growing pressure to finish the project — after writing about Arabians, Lipizzans, Clydesdales and Morgans — Henry started a section dedicated to burros and mules. She confessed she knew little about burros until librarian Mildred Lathrop passed along McKee’s article. “Before I finished that chapter in the Album of Horses, I knew that my next book would be Brighty of the Grand Canyon,” Henry said in a 1968 interview.

Born in Milwaukee, Henry began writing at age 7. After selling her first article to a women’s magazine when she was 11, Henry said she decided, “This is a very pleasant way to make a living.” She loved research, too. “I go to the library to learn as much as I can about the subject and locale,” she said. “As my father used to say, ‘To know what to ask is already to know half.’ ”

Henry headed to the Canyon and rode a mule from rim to rim “so that I could travel all of Brighty’s haunts.” She visited Ribbon Falls and drank from Bright Angel Creek, nibbling the white bursage and grasses that Brighty once munched on. Despite warnings about mountain lions, she camped at Cliff Spring and spent a night cowering in her sleeping bag after a big cat came by for water — an episode that helped her write the terrifying passage when a cougar attacks Brighty in the very same grotto.

Henry filled “notebook after notebook with material,” collecting anecdotes and confirming details from anyone with Brighty memories. But she couldn’t find McKee, who had moved to Southern California.

To accurately portray burro behavior, Henry hoped to bring a wild donkey back from the Canyon, explaining,

“I, for one, can’t write about an animal character unless he is part of our establishment.” But she returned home without one before finding a burro named Jiggs at a farm near Mole Meadow, her spread in the Fox Valley northwest of Chicago.

“I wanted to shove my fingers into his coarse, shaggy coat and feel how different he feels from a horse’s coat,” Henry said. “It’s much rougher and longer, and then of course he has those beautiful eyes, great big brown eyes with the white rim around them, so they’re very wistful, sort of. Then you have the white nose. And enormous ears that wiggle-waggle all while you’re talking, as if he doesn’t want to miss a word of what’s going on.”

Henry completed Brighty in longhand in a three-ring notebook, then hired someone to type the manuscript. A month after the novel’s 1953 publication, Henry received a letter from McKee, whose wife had bought a copy of Brighty for their 10-year-old granddaughter. McKee commended the book for having “plenty of pep” and added that “the pictures are admirable.” Such praise was no doubt welcome, particularly from a person so intimately acquainted with Brighty’s story. But McKee’s letter also disclosed something far more meaningful.

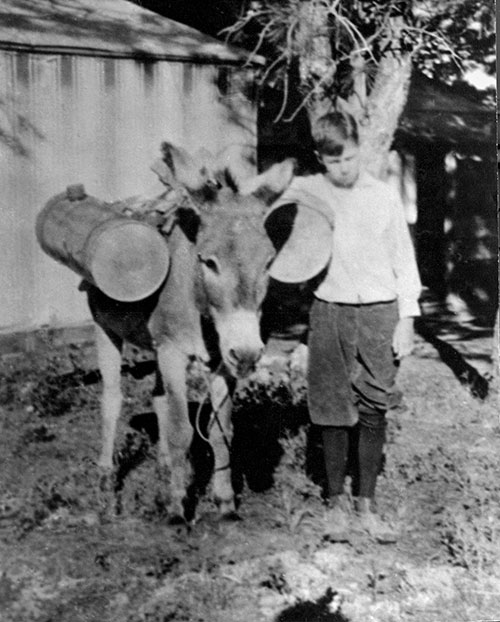

Henry tried to incorporate elements from Brighty’s life whenever possible. Sometimes she repurposed details: The gold watch found at the campsite became one of the Old Timer’s possessions, and Brighty was snowbound not with strangers but with Owens and Irons, the Old Timer’s killer. Henry also surmised Brighty probably had as a companion a boy “who understood the working of a burro’s mind and soul.” But, unable to confirm her hunch, she reluctantly invented the character of Homer Hobbs.

McKee enclosed a photo of Bob riding Brighty and wrote, “As my wife and I read your book, we knew in a twinkling that our son was the Homer Hobbs of your story.” Henry regarded this revelation as one of the three miracles she associated with Brighty, concluding, “Surely God takes faltering writers by the hand and leads them in the paths of truth.”

Brighty Goes to Hollywood

After reading Brighty aloud for his sons, Detroit-area filmmaker and television producer Stephen F. Booth decided the book should be a movie. By then, Brighty had been out for a decade, so Booth assumed Walt Disney, his friend through a shared interest in model railroading, had already purchased the rights. But when Booth contacted the book’s publisher, he discovered the rights were available.

“When Walt Disney found out, he said, ‘No, that can’t be; I own the rights to [Henry’s] novels,’ ” recalls Booth’s son Charles — who, like his father, is a producer and director. “Walt probably went back and had someone check on it that day. But my dad was a dreamer. I think that’s why he and Walt Disney got along.”

Shooting Brighty’s story posed daunting challenges, especially because Booth planned to film some of the movie at the Canyon itself. Preproduction lasted for two years — and, as Booth explained in an interview for the film’s DVD, “Everything had to be worked out ahead of time. We couldn’t invent things as we went along.”

Ferrying cast, crew and gear, a Hughes helicopter flew nearly 2,000 sorties between rim and river. A cable tram used when Irons forces Brighty to cross the Colorado required five weeks of construction. Booth drove 250 miles on North Rim back roads in a Chevy pickup to find an authentic log cabin, which then was dismantled, transported and reconstructed on location. Animals had to be wrangled for almost every scene: a burro, of course, but also mountain lions, hunting hounds, a porcupine, deer, a ringtail and a chuckwalla.

The film ended up sharing a cinematic pedigree with Citizen Kane. Screen veteran Joseph Cotten, who co-starred in the legendary Orson Welles film, played Owens, growling his way through lines such as “I bet that polecat is headin’ up for Flagstaff right now to file a claim.” Charles Booth says Cotten was “a down-to-earth guy,” despite his taste for high-end cars: “It was early Sunday morning, and there was Joe Cotten. He said, ‘Hey, young Mr. Booth, you’re from Detroit, but did you ever see one of these?’ He pointed to his two-tone Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost and said, ‘Let’s go for a ride.’ So, we went for a drive around the North Rim.”

As director and screenwriter, Booth hired Norman Foster, another Welles alum and a veteran of Disney’s Davy Crockett television miniseries. Foster had extensive experience on remote locations in Mexico and the Southwest, and his 1952 documentary Navajo had earned two Academy Award nominations. As Homer Hobbs, Foster cast Scottsdale’s Dandy Curran, a veritable All-American boy — the son of a former Miss America and an Arizona State College (now University) alum who had played for the Green Bay Packers.

Courtesy of Everett Collection

But what about Brighty? As a friend of Foster’s asked in a 1966 Arizona Highways article, “Where are you going to find the combination of a Marlon Brando and a Jimmy Dean to play the burro?”

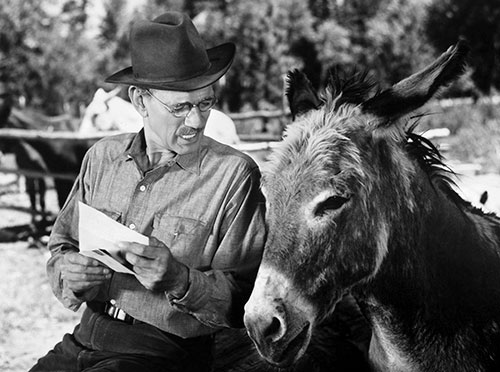

After screen-testing donkeys by the dozen, the frustrated Foster contacted Henry. She suggested Jiggs — and, after an audition at Mole Meadow, Jiggs got the gig, then was vanned 2,000 miles to a Grand Canyon corral with a star above the gate. Jiggs proved game, even if he didn’t do his own stunts (there were stand-ins). But while Henry could give voice to Brighty’s thoughts, short of going the full Mr. Ed, the filmmakers were limited in portraying the inner life of a burro. Thus, Jiggs spent much of the movie standing around while Cotten and others provided exposition.

Filming lasted a few months, during which conditions ranged from deep rim snows to 112-degree heat along the river. In a time before green screens, Foster captured memorable shots at Ribbon Falls and other landmarks as Brighty scampered through a lupine-filled meadow and brayed over the Grand Canyon’s dramatic abyss.

With the movie in the can, Booth returned home to raise more money to cover postproduction and distribution. Using a 16 mm Graflex projector to screen sample reels in Michigan living rooms, he eventually assembled 130 backers. The investors got not only a brush with moviemaking glory but also numbered miniature Brighty bronzes, based on a full-size sculpture Booth had commissioned from sculptor Peter Jepsen.

Jiggs’ film career lasted about as long as Curran’s. But the co-stars took a bow as they rode in a Brighty-themed float, complete with faux Grand Canyon rock, during Detroit’s nationally televised Thanksgiving Day parade.

Brighty in Exile

In 1978, Brighty got canceled.

The long history of burros in the Southwest dates to their arrival with the Spanish in the 1500s, and in the 19th century, the animals became a prominent presence in the Canyon as prospectors brought them in to haul loads. Sure-footed on rocky slopes and opportunistic eaters able to survive on marginal forage in the arid environment, escaped and released burros thrived in the Canyon. Some people claimed the feral burros had merely reclaimed an ecological niche once occupied by ancient relatives, and Henry celebrated Brighty not as an invader but as a native animal who “seemed part of the dust and the ageless limestone that rose in great towering battlements behind him.”

But biologists considered the Grand Canyon’s burros a major environmental threat. They decimated native vegetation and outcompeted native animals such as desert bighorn sheep for food while fouling water sources, accelerating

erosion and destroying topsoil.

By Brighty’s time, the park’s population had reached 2,000 animals in three main herds, leading National Park Service Director Stephen T. Mather to dub burros “a veritable pest” as he advocated “to eliminate the burro evil.”

None of this was the burros’ fault. As part of a strategy intended to benefit deer and bighorns, from 1906 to 1923, government hunters killed nearly 700 mountain lions,

3,000 coyotes and 120 bobcats in the Canyon, according to one 1962 analysis. Not only did burro numbers boom, but the Kaibab Plateau’s deer population exploded before an infamous die-off in the 1920s. Meanwhile, the Park Service began killing burros — lots of them — on annual hunts. One park superintendent’s wife warned her husband that so many gunshots could be heard from the rim that “it sounded like the Battle of the Bulge.”

Yet burros survived, and neither the literary Brighty nor the cinematic version made things any easier as the Park Service sought to eradicate the animals in the 1970s. Burros had come to symbolize the Canyon, and Brighty gave an endearing personality and winsome face to all of those otherwise anonymous donkeys below the rim. So, in 1978, the Park Service banished the 600-pound Brighty bronze that Booth had donated, and an exhibit detailing the environmental impacts of burros took its place. Brighty became burro non grata.

He was exiled, but not forgotten. Henry lamented the statue’s removal and protested the ongoing killing of burros. There were hearings, studies and environmental reports, and people on both sides of the issue deluged the park and politicians with thousands of letters. Kids pleaded, “Don’t shoot Brighty,” and as a Backpacker magazine article titled Up to Our Ears in Asses put it, “When word spread that burros were being killed, those children thought of cuddly Brighty.”

Others spoke of “burrocide” and likened plans to kill the animals to the removal of the Havasupai people from their ancestral lands in the Canyon. But environmentalists lamented how the Brighty-generated romantic image of burros as lovable Old West survivors had overwhelmed science.

Caught in a public relations disaster that had recast rangers, the admired stewards of America’s national treasures, as rifle-toting ass assassins, the Park Service agreed to an audacious and expensive plan proposed by the Fund for Animals. Using money raised in a national campaign, for 14 months starting in July 1980, the organization airlifted 577 burros from the Canyon at a cost of around $1,000 per animal. Some burros ended up floating down the Colorado on pontoon boats, and Patt Morrison of the Los Angeles Times dubbed the rescue effort “a donkey Dunkirk.”

With the burro dilemma largely solved, the national park rehabilitated Brighty’s reputation. The prodigal burro returned to the North Rim, where his bronze was rededicated in the Grand Canyon Lodge sunroom in 1981. Four decades later, Brighty is still there, his nose rubbed to a brassy shine by thousands of hands, large and small. And Henry’s description in the novel, of when Brighty sees the North Rim again for the first time in years, rings true:

“A delicious home-feeling welled up in Brighty. He wanted to run, to bray. In spite of his weariness he was conscious of an old remembered joy. … He had completed the journey. This spot of earth was Home.”