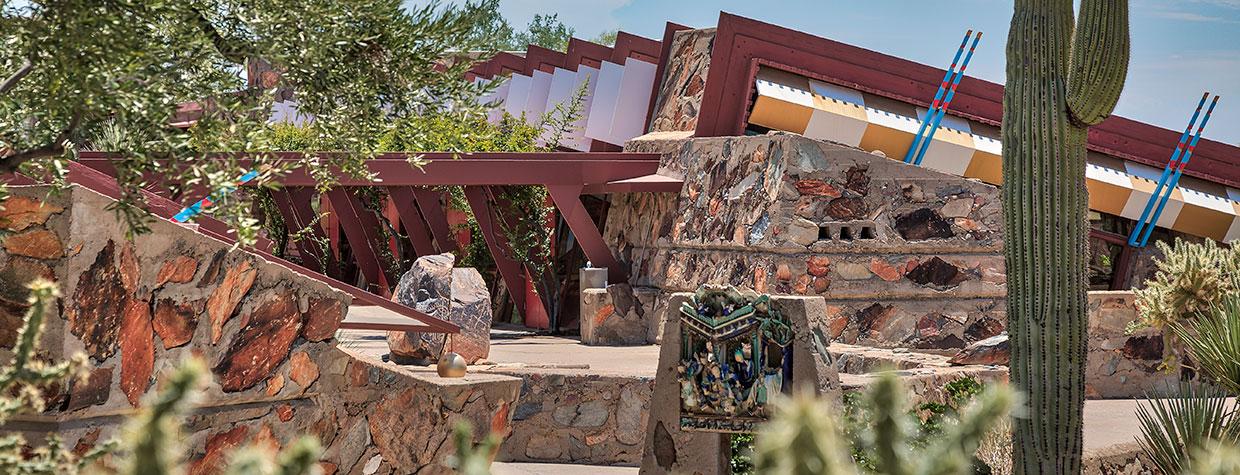

Under a cloudless morning sky, 10 architecture students from Washington State University and their professor roll out yoga mats on the lawn of a secluded courtyard at Taliesin West (pictured), Frank Lloyd Wright’s winter camp and architectural compound in Scottsdale. For the next hour, the group is guided through poses, proper breathing and mindful meditation. The rest of the day is filled with a tour of this National Historic Landmark and UNESCO World Heritage Site, classwork in the compound’s original drafting studio and an exploration of desert shelters built by Wright’s apprentices and previous students. In the evening, before retiring to their rooms at Taliesin West, the group shares cooking duties in the central kitchen to create a six-course dinner.

This weeklong program is part of the Taliesin Institute, launched in 2022 by the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation — which owns and operates Taliesin West and Taliesin, Wright’s original home and studio in Wisconsin — to engage university students and design professionals in learning experiences that channel Wright’s philosophies. “We are distilling Wright’s method of learning by doing, and using the site for experimentation,” says Jennifer Gray, an architectural historian who joined the foundation from Columbia University to launch and run the Taliesin Institute. “This is not a degree-granting program, but we collaborate with academic and professional groups to come up with programming that suits their needs.”

The Taliesin Institute is both a nod to the past and a glimpse of the future for Taliesin West, founded by Wright in 1937 on several hundred acres at the base of the McDowell Mountains. For decades, Wright worked with apprentices, collectively known as the Fellowship, to build and maintain Taliesin and Taliesin West and to work in the drafting studio on his architectural commissions. Particularly at Taliesin West, which he called a “camp,” Wright experimented with materials and forms, mining the desert for inspiration. The hardy band of apprentices — who lived on-site in tents, shelters, cottages and apartments — gained hands-on knowledge about site planning, construction and design, not to mention practical skills such as cooking and landscaping. The arts were encouraged via musical and dance performances, painting, sculpture, weaving and more. After Wright’s death in 1959, the apprentices carried on his architectural practice as Taliesin Associated Architects; by the 1990s, the apprentice program morphed into a formalized, accredited and degree-granting school.

However, in 2003, the architectural practice disbanded, and in 2020, the school parted ways with the foundation and moved to a different location. “The Taliesin Institute is not intended to replace the former school,” Gray says, “but we want this site to continue being an active learning space, like Wright originally intended.”

Gray points out that the Taliesin Institute isn’t strictly about architectural studies. More esoteric explorations are encouraged, following Wright’s example of being interested in the arts, society, politics, sustainability and more. The Washington State group, led by professor Ayad Rahmani, blended in literature while soaking in Taliesin West’s angular and organic architecture. The group read works by Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau and other American writers. “The idea was to explore what Wright and literature were grappling with during the architect’s time,” Rahmani says. “In his day, Wright was not just educating architects; he was educating humans.”

Another group, from Arizona State University’s humanities department, explored sound at Taliesin West, “sound-mapping” and recording everything from the crunch of gravel on walkways to acoustics inside buildings, proving architecture can be enjoyed via sound as well as sight. And University of Pennsylvania students spent several days learning about concrete preservation by doing chemical tests and scans of Taliesin West’s desert masonry walls, then built a sample wall of desert masonry concrete using the same methods the apprentices used to build the site in the 1930s and ’40s.

To date, more than two dozen schools and close to

700 students have participated in the programs at Taliesin West, staying for as little as a day or as long as a month. During hot months, the programs move to Taliesin in Wisconsin. While most of the programming is geared toward academics and design professionals, there are opportunities for the public in the institute’s online and in-person lectures and classes. Outside of the Taliesin Institute, Taliesin West’s tours are a good way for individuals to learn about Wright and his architecture, and the site’s public programming includes regularly scheduled concerts, lectures and film screenings, not to mention yoga and tai chi classes and sunset happy hours.

Back on the lawn, the Washington State students finish up their downward dogs and sun salutations, their minds recalibrated and ready to soak up knowledge. “The goal of the Taliesin Institute is to create a community of learners,” Gray says, “and, in the process, to raise awareness not only about architecture, but about ourselves and our society.”