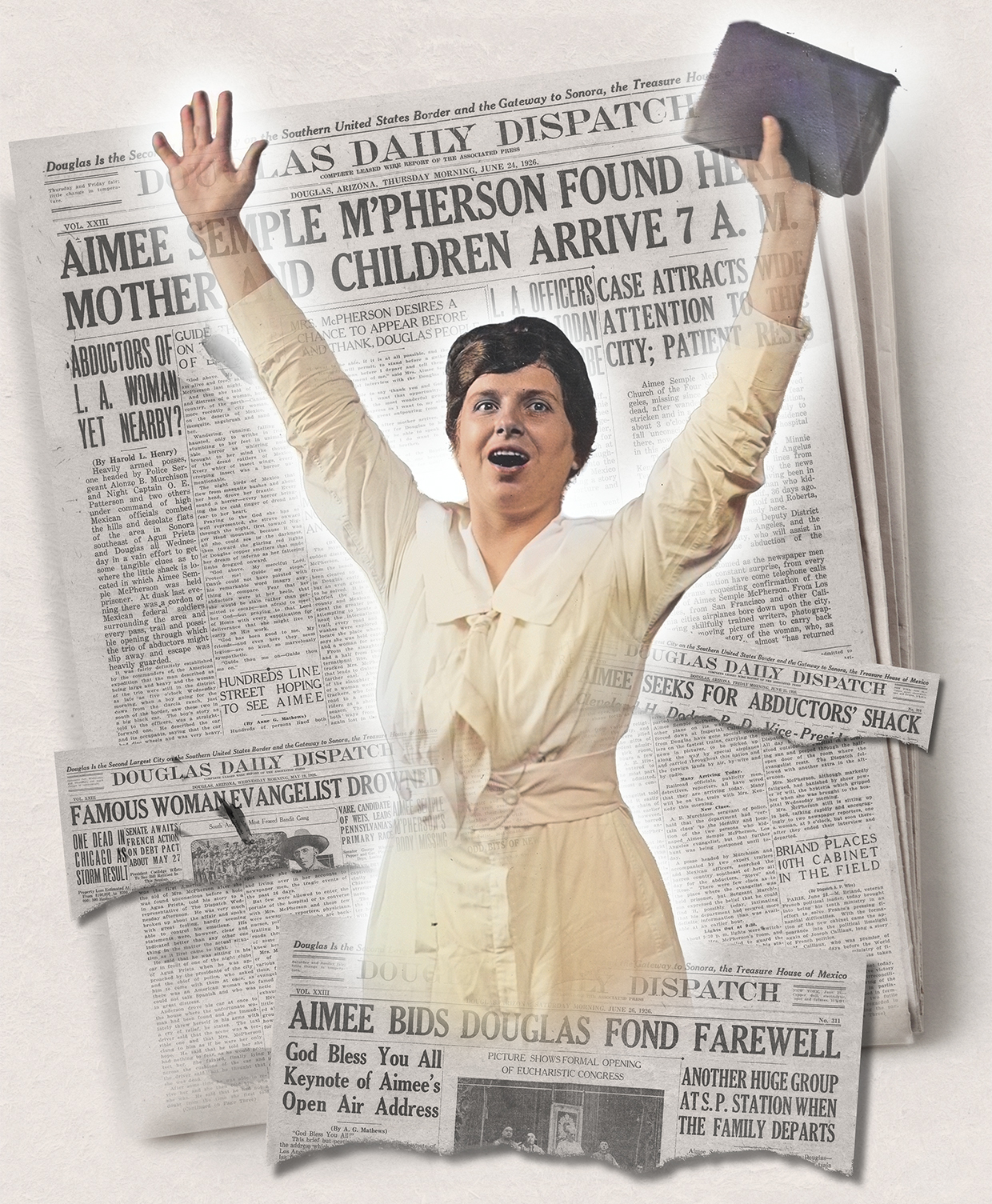

A few hours before a summer dawn, evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson walked out of the Chihuahuan Desert and came back from the dead.

Five weeks earlier, on May 18, 1926, McPherson, one of Southern California’s most famous women, had vanished while swimming near Venice Beach. Her followers held daily vigils along the shore as the ocean search failed to locate McPherson’s body. Although the Los Angeles coroner refused to issue a death certificate, 12,000 mourners gathered on June 20 for memorial services at McPherson’s Angelus Temple.

Three days later and 600 miles away, the custodian of a slaughterhouse on the border near Douglas, Arizona, and Agua Prieta, Mexico, was sleeping outside. Awakened by his dogs, he saw a distraught woman on the Mexican side. Despite his pleas for her to come through the border fence for help on the U.S. side, the woman began walking more than a mile toward Agua Prieta; then, she collapsed at the home of local bar owner Ramón González and his wife, Teresa.

It wasn’t until jitney driver Johnny Anderson arrived to take the mystery woman to a Douglas-area hospital that it became clear who she was. Desperately clinging to Anderson, the woman declared she was Aimee Semple McPherson and that more than 12 hours earlier, she had escaped kidnappers in Mexico and fled through the desert. Thus began one of the most famous events in Douglas’ history.

In the preceding days, the Douglas Daily Dispatch had published the kinds of articles typically found in a small-town newspaper. There was the tragic — a Douglas man suffocated when his Ford roadster overturned and crushed him — as well as the lighthearted, including the headline “Rancher Ropes Porcupine at Mud Springs.” A “splendid bill of vaudeville” was set for G Street’s Grand Theatre, while the Douglas Blues baseball team languished in fourth place in the Copper League.

When the outside world learned McPherson was alive, Douglas, population 9,000-plus, became ground zero for a media frenzy supercharged by the emerging medium of radio, the rise of celebrity culture, and the intense competition among the more than 2,000 daily newspapers published in the United States during the 1920s.

The story had it all: kidnapping, a famous woman in deadly peril, a miraculous resurrection, the border, hints of sex and infidelity, financial shenanigans. And two irreconcilable perspectives: the skepticism of those who doubted McPherson, and the fervor of both her true believers and the starstruck masses.

Each day atop its front page, the Dispatch ran a banner touting Douglas as the “Second Largest City on the Southern United States Border and the Gateway to Sonora, the Treasure House of Mexico.”

By 1920, Douglas was a prosperous town where two smelters processed copper ore from the mines of Bisbee. Opened in 1907, the stately Gadsden Hotel, with its marble lobby and 160 rooms, ranked with Arizona’s finest. More than 30 freight and passenger trains rumbled through town daily, and border crossings rose sharply as Americans flocked to the nightclubs of Agua Prieta after the 1920 advent of Prohibition.

With their close economic and cultural ties and geographic isolation, Douglas and Agua Prieta mostly functioned like a single city. But during the Mexican Revolution, gunshots, explosions and bugle calls echoed through Douglas’ streets as townspeople watched major battles in Agua Prieta from their rooftops. And the unsettled situation in Mexico led the U.S. Army to establish Camp Harry J. Jones to guard against potential raids by Pancho Villa’s forces.

McPherson’s reappearance set off an invasion of a different kind. Reporters descended from hundreds of miles away. Both the Los Angeles Times and the Los Angeles Examiner flew in reporters and photographers, who quickly turned back around to deliver their exclusive images. The New York Times ran front-page articles, and newspapers in cities as distant as Sydney, Australia, published McPherson’s account.

The data was primitive but telling: More than 100,000 words went out over the Western Union telegraph, and at least 400 telephone calls were placed between Douglas and the West Coast. There was quite a story to tell. In McPherson’s narrative, a man and a woman (whom she later called “Mexicali Rose”) approached her at the beach. They pleaded with the evangelist to minister to their dying baby in a nearby automobile. When McPherson approached the car while still in her beach attire, they subdued her with chloroform.

Hours later, McPherson came to in a desert shack. She saw a third abductor, she said, and claimed the kidnappers tortured her with a lit cigar. After four weeks, they took her to a second shack where, a few days later, they left McPherson alone. She said she rolled across the floor to reach a large tin can and used its lid’s jagged edges to saw through the ropes that bound her hands. She untied her ankles, then set out across a desert thick with mesquites, cactuses and catclaw.

Temperatures hovered around 100 degrees before nightfall, and McPherson continued through rugged desert lit only by the moon. She covered more than 20 miles, a journey the Dispatch vividly described: “Wandering, running, falling exhausted, only to writhe in fright, stumbling to her feet in unimaginable horror as whirring noises brought to her mind the thought of the dread rattlers of Mexico. … The night birds of Mexico that flew from mesquite bushes and about her head drove her frantic. Every sound a horror — every horror bringing the ice-cold finger of dread and fear to her heart.”

Even as she neared safety, McPherson found no relief, the paper added: The “glaring red lights of Douglas’ copper smelters made her dream of inferno.”

As word spread that McPherson was at the hospital, crowds gathered, “whispering and wondering how Douglas was selected by fate for the ‘Resurrection,’ ” according to the Dispatch.

But questions quickly arose. When she found help, McPherson was neither sweaty nor sunburned. Her lips weren’t chapped, and according to Teresa González, she didn’t ask for water until an hour after she showed up.

An examination revealed minor wounds on McPherson’s wrists and some blisters and cactus needles on her feet, but not the injuries one might expect to suffer during a trailless desert trek. Her gray dress was clean, and her black leather slippers showed little wear. She wore a corset, an odd item for kidnappers to provide her — and for her to leave on in the desert heat.

McPherson also mentioned the shack from which she’d escaped had a wooden floor, an uncommon feature in a region where most buildings still had earthen floors. Mexican and Douglas law enforcement, along with posses of townspeople and even local schoolboys, fanned out to search for the shack. McPherson joined in, too. But no shack matching her description was found.

When she emerged from the desert, McPherson was 35 and at the peak of fame after the long journey from the Ontario, Canada, apple farm where she’d grown up. Her mother, Minnie Kennedy, was a devoted member of the Salvation Army and had introduced McPherson to the religious life at an early age. The young McPherson had a vivid imagination and theatrical flair, and she staged church services with toys as her congregation.

At 17, McPherson traveled by sleigh into town with her father, then persuaded him to attend a Pentecostal revival meeting led by Irish evangelist Robert Semple. Listening to Semple, McPherson recalled, “Cold shivers ran up and down my back”; the night, she added, was “the turning point of my life.”

She not only had a religious awakening but immediately fell in love with Semple. Two months shy of her 18th birthday, the couple married, and in 1910, they sailed for China to serve as missionaries. But shortly after arriving, they came down with malaria; Robert, who also contracted dysentery, died. Their daughter, Roberta, was born 29 days after Robert’s death.

Back in the U.S., McPherson remarried, then gave birth to her son, Rolf, in 1913, before her religious passions inspired her to hit the road. “I took my suitcase and my babies, and I started off in the night, got a taxicab and went to the depot,” she recalled. “Started off to preach the word of God. I was invited to this town and that town. Preached outdoors under the trees, preached in the piazza, preached on the street corner. … I preached from Canada clear to Key West, Florida. By winter and summer. In tents or in open air.”

Wearing her trademark white nurse’s dress with a military cape, McPherson crisscrossed the country six times in seven years. Traveling with the children, she and Kennedy drove an eight-cylinder Oldsmobile dubbed the “Gospel Car” and emblazoned with the question, “Where Will You Spend Eternity?” At night, they knelt on the running board and prayed.

During a time when female preachers were controversial, McPherson filled huge auditoriums around the country. She then saw her future in booming Los Angeles, where she arrived in 1918 with $10 cash and a tambourine. She toured to raise funds for a house of worship for her Foursquare Church, and in 1923, she opened the Angelus Temple.

She preached salvation, not damnation, and the temple — a gigantic indoor Roman amphitheater considered the country’s first megachurch — was designed to uplift her followers. Painted blue to resemble the sky and complete with billowing cumulus clouds, the dome shimmered with bits of abalone shell. McPherson said, “I wanted it like God’s own outdoors.”

A pair of radio antennae rose from the roof. McPherson recognized how radio could help her save souls far beyond Southern California, and she became one of the first women in the U.S. to acquire a radio license. In 1924, she launched KFSG and became a pioneer of electronic evangelism.

McPherson produced Hollywood-style spectacles she called “illustrated sermons.” One featured cannons fired from a full-size sailing ship; another, a Trojan horse. There was a 100-voice choir, bell ringers, an 80-piece xylophone band and even live lions, tigers and camels. She once took the stage dressed as a traffic cop on a motorcycle and delivered a sermon urging congregants to slow down long enough to be saved.

A Los Angeles newspaper wrote, “If Aimee Semple McPherson had not chosen to be a revivalist, she could have been a queen of musical comedy. She has magnetism such as few women since Cleopatra have possessed.”

Douglas swooned during McPherson’s recovery. Flowers sent by locals filled her room, and McPherson proposed building a Douglas branch of the Angelus Temple to thank the community for its kindness. The Dispatch promoted her account of the kidnapping and ran unverified reports that the mystery shack had been found.

In a gushing front-page note, McPherson wrote, “The friendships here, I feel sure, will be sincere and lasting. The friendship born in the heat of an hour welds and forges sacred bonds.” Before boarding the 9:10 p.m. Southern Pacific train for Los Angeles, she bade Douglas farewell at a prayer meeting attended by 5,000 people at 10th Street Park.

The city didn’t hesitate to promote its connections to McPherson. The Chamber of Commerce produced stickers declaring, “Aimee Slept Here,” while Anderson, the cab driver, lured passengers with the promise of riding in the same vehicle that carried McPherson to safety as the Dispatch trumpeted, “All Aboard the Aimee McPherson-Douglas Special.”

“We all gave Mrs. McPherson the benefit of the doubt and in so doing endeared ourselves and our city to her,” the newspaper declared. “[We] all did ourselves proud. Why? First, because this town is made up of hospitable people.”

A crowd of 30,000 greeted McPherson when her train rolled into Los Angeles. But a happy homecoming proved short-lived: A grand jury began to investigate whether she had committed criminal conspiracy. There were too many holes in her story — too many reports of sightings everywhere from Edmonton to Tucson, as well as accounts of her traveling freely in Mexico. More damning evidence suggested that, starting the day after her disappearance, McPherson had shacked up for 10 days in a Carmel, California, cottage with Kenneth G. Ormiston, the Angelus Temple’s radio operator.

The grand jury extended the McPherson drama for several more months. Douglas locals testified, and prominent officials, including the mayor, issued a statement declaring they believed McPherson’s story. But Mexican officials had doubts from the start, especially about footprints found outside Agua Prieta that matched McPherson’s shoes. “If she did make them, then she could not have been wandering around all over the desert here,” argued Agua Prieta politician Ernesto Boubion, “but would have been the passenger in an automobile.”

McPherson, her mother and Ormiston were eventually indicted, but in January 1927, the Los Angeles district attorney suddenly dropped all charges, believing a guilty verdict was unattainable.

McPherson, having survived the scandal, continued her work until she died of an accidental barbiturate overdose in 1944, at age 53. Her son, Rolf, then guided the ministry for 44 years, and the Foursquare Church has grown to nearly

9 million members in 150 countries.

But Aimee Semple McPherson never did fulfill her vow to build a church in Douglas. Nor did she ever come back to town.