During their brief marriage in the 1920s, writer and photographer Elizabeth Compton Hegemann and her husband, Michael Harrison, lived on the South Rim of the Grand Canyon, where Harrison worked as chief clerk at the newly established Grand Canyon National Park.

“We lay supreme in our little world, flanked by the great, colorful depths of the Canyon and the miles of pine-covered plateau stretching south to the San Francisco Peaks,” Hegemann wrote in the 1963 book Navaho Trading Days, a memoir of her Arizona years. “A single track of steel bound us to the main artery of travel at Williams, over which each morning came our precious water supply in tank cars on the regular freight train. … It was our lifeline. Nothing existed as yet in winter on the North Rim except the deer herds and the white-tailed Kaibab squirrels, so when we looked across that twelve-mile-wide chasm to the eight-thousand level on a winter’s night, not a light was to be seen.”

The South Rim of those years was a tiny community populated by such Canyon characters as the great Swedish painter Gunnar Widforss, Fred Harvey employees and a dozen National Park Service personnel. Harrison’s staff consisted of a stenographer and a bookkeeper, and Hegemann’s $1 park automotive permit was valid for an entire year.

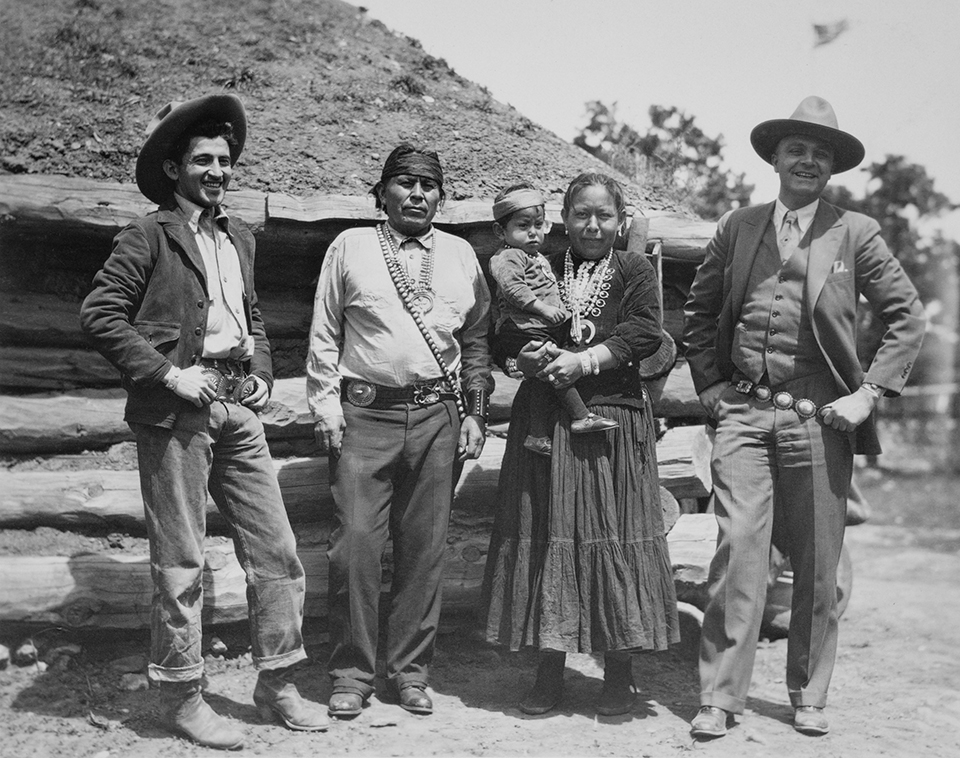

Born nine months apart and still in their 20s, the couple cut charismatic figures. Known among the area’s Navajos as Asdzáán Nez (Navajo for “Tall Woman”), Hegemann had taken to wearing handmade, traditional Navajo skirts and black and crimson velveteen blouses accessorized with “necklaces and bracelets of heavy old silver or colorful turquoise and coral.” Harrison, lean and with a warm smile, had a dashing, confident bearing, whether in his Park Service uniform or a pair of Levi’s cuffed just so over cowboy boots, and with a neat dimple in the high-crowned, Navajo-style cowboy hat he sported at a jaunty pitch.

For $10 a month, the couple lived in “cramped government quarters” with their cat, Señor Tomaso Tabasco Chilipepper. Unlike other South Rim employees, they socialized with the Navajos and Hopis who worked at the Canyon. The Hopi men even crafted a drum for Harrison and frequently visited the couple for singing and chanting that extended past midnight.

“Altogether, it was a fascinating and almost unreal background in which to make one’s home, if all the beckoning potentialities were to be explored,” Hegemann wrote. “Mike Harrison and I tried to do just that. … The surrounding country became a part of us, or at least we became an integral part of it.”

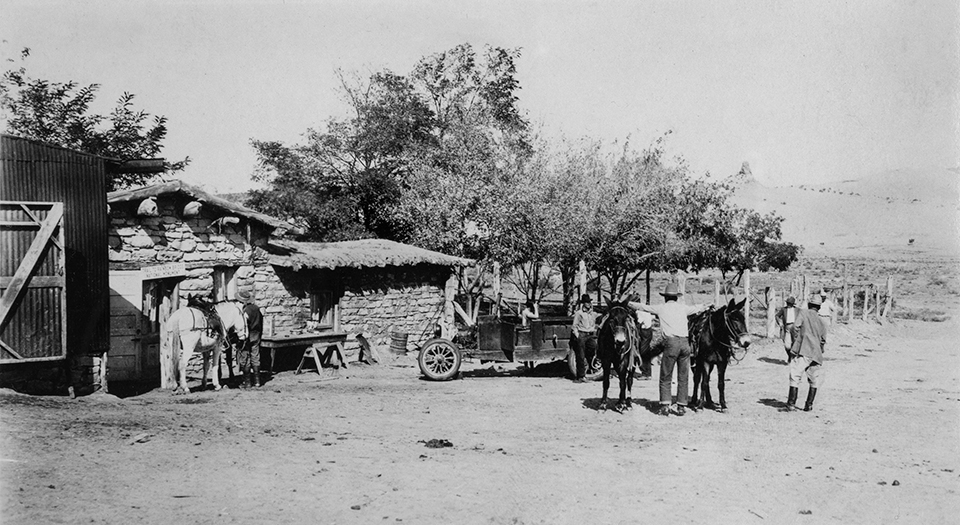

The couple explored Arizona in an era when the state was straddling the narrow margin between ancient and modern. They traveled by horse, by burro and in their red 1923 Buick touring car, following rough tracks and crossing washes of quicksand in the Painted Desert en route to the Hopi mesas and remote Navajo lands. They attended a Navajo purification and healing ceremony that continued for three days and nights of dances, singing, races and feasts.

Hegemann and Harrison were among the first few hundred bilagáana, a Navajo term for white people, to reach Rainbow Bridge. They befriended elders who had escaped Kit Carson’s raids and saw the first airplane land on the northwest Navajo Nation in 1927. The Navajos called the plane a chidí naat’a’í, or flying automobile. “I could hardly grasp the full significance,” Hegemann wrote. “We were quiet in our contemplation of the past and in our wonderment of what the future might hold.”

But something didn’t work. Hegemann offered no details in Navaho Trading Days, only a quick aside that by the fall of 1928, “Mike and I had written finis to our marriage.” Harrison lived in the Southwest for a few more years before taking a job with the Bureau of Indian Affairs in California. He maintained a lifelong interest in the Southwest and went on to amass a 21,000-volume library of printed materials, as well as a large collection of Indigenous crafts.

Eyes wide open and camera at the ready, Hegemann remained in Arizona and embraced “the free, simpler life of the vast Navaho Reservation.”

Navaho Trading Days is a remarkable, if uneven, record of Arizona in the 1920s and ’30s. Hegemann was a good writer and a vigilant observer, but the book unfolds as a series of episodes rather than building into a fully realized narrative. And while Hegemann was deeply respectful of Navajo culture, her repeated use of the slang term “Navvies,” intended as an endearment, sounds tone-deaf by current standards.

As a photographer, she was more documentarian than artist, capturing a rapidly changing world on the fly rather than carefully composing images. She initially used a simple Kodak before switching to a large-format Graflex, and the book’s low-quality image reproduction turns Hegemann into a literal shadow catcher as photographic details are frequently swallowed in silhouettes. Despite their flaws — or maybe because of them — her photos often take on a dreamy, even hallucinatory quality, like buried memories resurfacing unbidden.

Born into a prominent Cincinnati family in 1897, Hegemann might seem an unlikely chronicler of the changing frontier. She attended exclusive prep schools and the New England Conservatory of Music, and at 19, she married naval aviator Lieutenant William M. McIlvain after meeting him at a military ball in Coronado, California. An engagement announcement described Hegemann as “a well-known beauty who has attracted attention in society all over the country” and featured a pastel portrait of her by Louis Hels, a renowned Parisian artist living in California.

Hegemann’s grandfather, businessman Charles Gove, founded a water company near San Diego in the 1880s. He collected Indigenous crafts and traveled on horseback through the Hualapai Tribe’s land to the Grand Canyon. With family based out West, Hegemann spent summers in California and first visited the Canyon while still a teen. She explored Navajoland north of Leupp in 1922 and stayed at El Tovar a number of times; the South Rim hotel was where she met Harrison in 1924, after her marriage to McIlvain had ended.

A year after divorcing Harrison, Hegemann married Harry Rorick, a blue-eyed Kansan who prided himself on his one-eighth-Cherokee bloodline and his family’s homesteading in Oklahoma during the 1893 Cherokee Strip Land Run. Rorick worked in the cattle business but had no trading experience when he and Hegemann bought Shonto Trading Post from the Babbitt family in 1929.

“The long-haired Navahos, their horses, and enormous herds of goats surrounded them on the outside,” one description of the trading post reads. “Inside were the wool, the goatskins, the stacks of Navaho rugs, and their pawn rack loaded with silver jewelry. That was Elizabeth Hegemann’s home during the next 10 years.” Trading local weavers for groceries and other staples, the couple bought rugs, usually at $1 per pound, and sold them in 90-pound bales to wholesalers in Gallup, New Mexico, while shipping 350-pound sacks of raw Navajo wool to carpet factories.

If it’s tempting to accuse Hegemann of Navajo cosplay or cultural appropriation, she did live the life. She spoke the language and cultivated traditional weaving skills — she washed, hand-carded and spun her own wool and gathered natural pigments for dyes. On brutal roads, she made frequent 250-mile round-trip runs to Flagstaff solo to pick up 50-gallon drums of gasoline. Driving the couple’s 1.5-ton pickup with its low first gear, Hegemann would leave Shonto at 4 a.m., hoping to return by midnight. “Sometimes I would stop a minute,” she recalled, “and from horizon to horizon there would not be another light nor a sound, just the great dark sky overhead. I grew to know every foot of the road and the bordering terrain.”

Then, in 1939, Hegemann sold her share of the trading post to Rorick, citing “personal reasons” that went unspecified other than a passing mention of her nearly 80-year-old mother, who lived with the couple. Later that year, she married her fourth husband, Anton Hegemann, a German national who had immigrated to the United States from Mexico. The 1940 census shows the Hegemanns living in Coronado, California.

“I would not care to return to trading,” Hegemann said in a 1957 Los Angeles Times article. “The modern Indian chugs over the landscape in trucks and jeeps; the primitive was passing. Truly, my home was actually like our West of 100 years ago.”

Hegemann eventually moved to Albuquerque and lived in a 1,000-square-foot adobe built in 1941. Her trading days gave her enough expertise to write about Navajo silver for the esteemed Southwest Museum in Los Angeles, and she also collected and wrote about Spanish Colonial crafts and 17th and 18th century santos carvings.

In April 1961, Harrison learned from mutual friend Horace M. Albright, the noted conservationist and former director of the Park Service, that Hegemann was working on a book. The former couple had fallen out of touch, maybe for decades, before Harrison wrote to Hegemann through University of New Mexico Press, the book’s publisher. “I hope the shock of hearing from me is not too great,” he wrote, explaining that he “made up my mind that the lights in this house wouldn’t be put out until I had written you offering my congratulations. And here I am.”

Delighted to hear from Harrison, Hegemann quickly responded. Galleys for the book, nearly 400 pages and with more than 300 images that she had spent years restoring, were coming in. She promised to send one of the first books to Harrison and his wife, Margaret, a renowned bookbinder, hoping they would enjoy her account “of the old days at Grand Canyon and on the Hopi and Navaho reservations when life was so much simpler, and the pace was decidedly slower.”

At the end of the letter, almost as an afterthought, Hegemann revealed her 15-year battle with “cancer in the chest.” She was dying. “Please keep this confidential,” she wrote, “as I like to keep the flag high in the last!”

Thus began a steady correspondence between the two, now preserved in the Michael and Margaret B. Harrison Western Research Center Collection at the University of California-Davis. In that pre-email, pre-text era, the couple exchanged nearly 30 letters, some running for several typed, single-spaced pages, with Hegemann frequently scrawling handwritten asides in the margins. They warmly reminisced about their times together before returning to the present and lengthy recitations of ailments as they detailed the declines and demises of those they knew.

One champion rodeo bulldogger’s death was particularly tragic, Harrison wrote: “Tom stopped his car to take a shot at a rabbit with his carbine, which was wrapped up in his camp bed. The muzzle was toward him, and he pulled on it with the usual result. He bled to death. … Rose took it pretty hard, and a couple of years later, while on the train to another show, she jumped off while the train was barreling along and was killed.”

The letters mix an appreciation of Hegemann and Harrison’s good fortune and a sadness bordering on resentment about the changes since the days when they’d camped in Monument Valley with Navajo friends, alone in the big country. Acknowledging that she and Harrison were “now the old-timers,” Hegemann wrote: “The beautiful untouched isolation of the northwest Navaho Reservation is now a thing of the past. … I never want to see it again. The hordes of tourists are beginning to stream through with their litter and beer cans and their silly behavior. The young Navahos think it is progress.”

Delays pushed back the book’s scheduled August 1961 publication. Hegemann blamed management and scheduling missteps resulting from what she characterized as the “favoritism and vindictiveness” of an editor and designer at UNM Press. “Everyone is telling me that they hope I have written the truth as I saw it, because so much hokum has been put out by others on the subject,” she wrote. “I have tried to keep it authentic in every detail. … There has been no attempt to pretty it up. Personally, it is too harsh for [the editor’s] taste, but it was a harsh and hard land in which the Hopis and Navahos and [white settlers] scratched for their living in those years, and [the editor] knows that I must keep this true picture.”

Unfortunately, Hegemann never saw the book in print. “Mrs. Hegemann died at age 65 in Albuquerque in April 1962, a few days after she read proofs and approved the sequence of photographs planned for Navaho Trading Days,” the dust jacket’s author description reads. Harrison learned about Hegemann’s passing from one of her Albuquerque neighbors.

Harrison would live another 43 years before dying at 107. Writing to one of his and Hegemann’s mutual friends, he concluded: “She was a remarkable woman, and it is a pity that this had to happen when she had so much to contribute to our knowledge of the Indians and the Southwest. … She was hoping to see her book off the press, but this was not granted to her. A funny old world, isn’t it?”

Photographs: Elizabeth Compton Hegemann Photograph Collection of Navajo Indians and the Southwest, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California, from Navaho Trading Days by Elizabeth Compton Hegemann, copyright 1963, University of New Mexico Press.