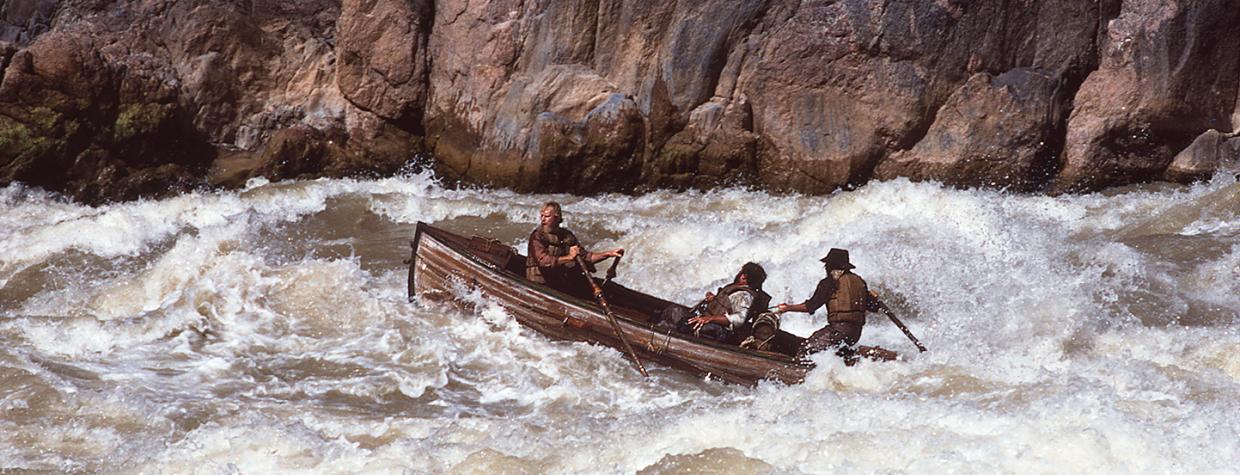

The rapid we started with this morning gave us to understand the character of the day’s run. It was a wild one. The boats labored hard but came out all right. The waves were frightful and, had any of the boats shipped a sea, it would have been her last for there was no still water below. We ran a wild race for about two miles, first pulling right, then left, now to avoid the waves and now to escape the bowlders, sometimes half full of water and as soon as a little could be thrown out it was replaced by double the quantity. Our heavy boat ran past the lead boat and we dashed on alone, whirling and rushing like the wind.

— George Bradley, Powell Expedition, August 19, 1869

One hundred fifty years ago, Major John Wesley Powell and five other battered, half-starved mountain men floated out the foot of the Grand Canyon. Powell brought the first detailed descriptions of the canyons of the Colorado River to the public, having descended the entirety of the river in wooden boats. He was lucky to have survived.

Running rapids in rowboats was an untested concept. Although voyageurs had long been descending rapids in canoes in the Far North, that did not translate to oar-powered craft. Powell, who had rowed a good deal of flatwater in the Mississippi River drainage before losing his right arm in the Civil War, went with his intuition. The fastest and most seaworthy cargo-hauling boat at the time was devised in New York Harbor for servicing ocean vessels. Called Whitehall boats, their hull design evolved over centuries of fine-tuning, and they were prized for their speed and capacity in Eastern ports.

To this day, Whitehalls remain the most sophisticated hull design ever to run whitewater. They are exacting, time-consuming and expensive to build. Their elegant lines are a joy to behold: a sharp cutwater in front, a sexy guppy belly through the center section and a graceful wine-glass transom that leaves little wake. Powered by one or two strong oarsmen pulling hard, with their backs downstream, they were steered from the rear with a tiller or, in Powell’s case, a long steering oar.

Unfortunately, they were a dreadful design for the rocky rapids of the Colorado. Although they were fast and carried a good load, they had a keel strip along the length of the hull. This made them difficult to turn and made rocks hard to avoid. They were quite narrow, making them marginally stable in the chaotic waves of the Colorado. Worse, steering necessitated moving faster than the current, so they struck the unavoidable rocks with tremendous velocity. If they broached sideways on a shoal, the keel strip would catch — dumping the boatmen downstream, then running them over. But the boats were only part of Powell’s problem.

I have given away my clothing until I am reduced to the same condition of those who lost by the shipwreck of our boat. I cannot see a man of the party more destitute than I. … The men are uneasy and discontented and anxious to move on. If the Major does not do something soon I fear the consequences. But he is contented and seems to think that a biscuit made of sour and musty flour and a few dried apples is ample to sustain a laboring man.

— George Bradley

Midway through the Grand Canyon, Powell’s party was nearly out of food, supplies and patience. Camped in the middle of what would become one of the most revered landscapes in the world, they could perceive it solely as a hostile threat in their race for survival. Only through strength, perseverance and sheer dumb luck did they make it through.

In the decades that followed, rivermen learned to row boats through rapids the way ferrymen move a boat back and forth across a river. By facing downstream and rowing upstream, boatmen could slow their downstream progress and cross more easily from side to side. They could avoid rocks and large waves, and thread their way down complicated channels. Pioneer boatman Bert Loper learned the technique from miners on Utah’s San Juan River in 1892. Utah trapper Nathaniel Galloway later evolved the technique on the Green River. Both men were using flat-bottomed boats with upturned ends, drawing little water and allowing them to pivot quickly. For the next 70 years, boatmen tinkered with the design: adding more rocker (raising the fore and aft), increasing center width for buoyancy and stability, decking more of the interior to avoid swamping. These boats were a definite improvement over Powell’s Whitehalls, but still very limited in terms of carrying cargo and passengers.

It was in Oregon that riverboats evolved furthest and fastest. By the 1940s, McKenzie River fishermen and boat builders had devised a boat with a very high prow, radically flared sides and a great deal of rocker. Form, as it often does in boat design, followed function. They called them “drift boats.” The prow was pointed downstream, into the waves, while boatmen slowed their progress by pulling upstream.

In the early 1960s, environmentalist Martin Litton brought drift boats to the Grand Canyon and decked them over. He called them “dories,” preferring the iconic New England term to the less fanciful “drift boat.” It was in these craft that river running in rigid boats finally became practical. Dories could haul a great deal of gear and comfortably carry four passengers. They were far more seaworthy than their predecessors. The weight of supplies to run a two- to three-week expedition serendipitously added ballast below water level, giving the boats tremendous stability. And they were drop-dead gorgeous. Litton wrote:

The dory is an ancient design. We didn’t originate it. It goes back into antiquity. There’s a kind of magic in terms of its stability and its ability to recover from extreme situations — self-righting practically. The boat is something beautiful to look at; it has lines that belong on the water.

For the first decade, Litton’s trips were, shall we say, quite adventurous, as he trained himself and his new, green boatmen in the art of river running and boat repair. But boatmen, by nature, are quick learners, and by the mid-1970s, Litton’s Grand Canyon Dories was offering regular trips through the Canyon in wooden dories. There was a not-so-subtle environmental ethic espoused on those trips. Litton felt that by connecting people to the river for that long, in those fragile, beautiful boats, they might go home changed and be willing to stand up and fight for wild and irreplaceable places being lost through development. Each dory was named for a place already destroyed or endangered: Glen Canyon, Hetch Hetchy, Lake Tahoe, Rainbow Bridge.

The dory ride is unique, the rigid hull telegraphing every subtlety of the river into your body. They give an unparalleled ride in rapids. And, yes, sometimes they tip over. But rarely. They usually are righted quickly and easily.

For most of Litton’s tenure at Grand Canyon Dories (he sold in 1987), he alone chose to use these barely practical, insanely beautiful boats. The rest of the river-running world had long since moved on to rubber rafts — sometimes rowed or paddled, but, for the most part, motorized.

“The fourth boat is made of pine, very light, but 16 feet in length, with a sharp cutwater, and every way built for fast rowing, and divided into compartments as the others. The little vessels are 21 feet long, and, taking out the cargoes, can be carried by four men.”

— John Wesley Powell

However, there was an indescribable lure to the dories. As time passed, more and more river outfitters added a dory or two — and sometimes a whole fleet — to their offerings. The dory’s popularity has spread throughout the private river-running world as well: Each year, more hobbyists buy or build a dory to run on rivers throughout the West. Kevin Fedarko’s popular 2014 book, The Emerald Mile, detailing a speed run through the Grand Canyon in a dory, has raised public consciousness of the craft, spiking awareness and demand. The inoculum continues to spread. Although traditional dories still are made of wood, many riverboats now are made from aluminum or epoxies. But the form remains the same: three elegant curved panels, flared on the sides, high at the ends. They are as different from Powell’s Whitehalls as a boat of that size could ever be.

The trip itself has changed immeasurably since Powell’s desperate struggle, too. Camp comforts abound; the food borders on gourmet; hikes are guided and selected for the weather, the group, the situation. Today’s experience balances the challenge and thrill of wilderness and whitewater with the skills and safety of modern techniques, giving participants security and the opportunity for life-changing adventure. The boats have gone from something feared to something revered. As unlikely as it seems, the quirky idea of running rigid wooden boats on rocky rivers has not only survived, but flourished.

As Litton said:

There’s a mystic thing about a dory to those of us who know them. I feel that anyone who looks at a dory and has to ask why you use that will never understand, no matter what kind of answer you give.