Editor’s Note: The disaster in Phantom Canyon is included in our book The Desert Cries by Craig Childs. It appears in two parts: an essay about the canyon, and a detailed account of the deadly flood. In the book, Craig writes: “I did not write these pieces to be read strictly as stories of disaster nor as cautionary tales. I also wrote them to reveal a furious and elegant beast that few people ever get to see.” Nevertheless, their invaluable purpose as cautionary tales cannot be overstated. Although it’s been more than 25 years since the tragic summer of 1997, the deadly realities of flash floods never wane. In this issue, we hope to inspire you to explore some of the state’s waterways. But when you go, it’s important to remember that Mother Nature plays by her own set of rules. Traveling into the wilderness, even on short trips, can be challenging and risky and requires careful planning before you begin. Your safety depends on your own good judgment, adequate preparation and constant observation. Know the weather forecast and flash flood potential before starting your trip. And if bad weather threatens, never, ever enter a narrow canyon.

Part One: Phantom Canyon

There is a hole where the water sings. The hole is a canyon that clamps down on itself. The place is called Phantom, one of the many canyons inside the Grand Canyon. A small creek wanders inside, its voice echoing in its descent.

It is early evening when I reach the hole, hiking for a couple days from the south, across a place called Utah Flats. I pull out my sleeping bag and start cooking dinner on a small stove.

Behind me, the land is a vast opening of cliffs and steep chasms, classic of the Grand Canyon’s interior. Sunset still holds the highest cliffs. Ahead of me is this plunging hole where bedrock is worn smooth. It stoops out of view. There are no plants in there, no customary boulders or small rocks. No broken cottonwood trees. No sand. No dirt. When my meal of rice and beans is ready, I walk with the pan in a gloved hand. Reaching in with a spoon, eating distractedly, I step around the edge of this hole. It is like walking the rim of a bowl clean as stainless steel. A huge boulder is jammed into a nick at the upstream end, turned smooth as ice by the polishing force of floods. Water of Phantom Creek strains into this place, running down a smoothed ladle of stone into a dusky canyon. The sound is opulent. Long tails of creek water spatter and gurgle. I crouch there on the rim, taking another bite. The water is a meditation, a sweet sound.

As the last light slips out and the stars come, I am still crouching there with this crystalline timbre of running water. This is why people place miniature, burbling fountains on their desks at work, why they linger beside rivers. The libretto tones of water settle the electrical storm of the mind. This little creek is alert, though, not sleepy. Every now and then it perks with a sudden high pitch. I’ve listened to floods, as well as these trickles of water. The voice is different, but it is still water song. It is still baritone and shrill at once.

The next morning, I gather a day’s worth of gear and walk upstream to follow the course of the most recent flood, a big September deluge from a month ago. By tracking the path of rubble, I will be able to find the source.

Entire groves of thin willows are bent to the ground, their leaves matted with mud and roots from upstream. The largest of the surviving willows are 17 inches in diameter. Anything larger did not bend in the flood. It broke. The big willows are gone.

Only the established cottonwood trees survived. The young ones were yanked out, their entire root balls twisted from the ground. If they weren’t dug out by the flood, they were severed, leaving broken stumps standing around like gravestones, some cocked in the direction of the flow, ragged tops decorated with hanging wreckage. Eight-foot-high bridges of broken cottonwood trunks stand locked together, the arms of branches linked. Logjams of 30 full-grown trees thrust into each other. Amid the debris I find the skinned leg of a fox. Claws and articulated toe bones are held in place by scrappy tendons. I sit on my haunches and lift the remains with my right hand. I rotate it. The four darkened toe pads are still in place.

Tracks of a trotting coyote show in the aftermath mud nearby. It came through sniffing at the fresh green snap of willows. Surrounded by upended trees and toppled boulders, the small tracks seem too individual, too cognizant, heading upstream instead of downstream. In view of the flood damage, they are as trivial as bystanders.

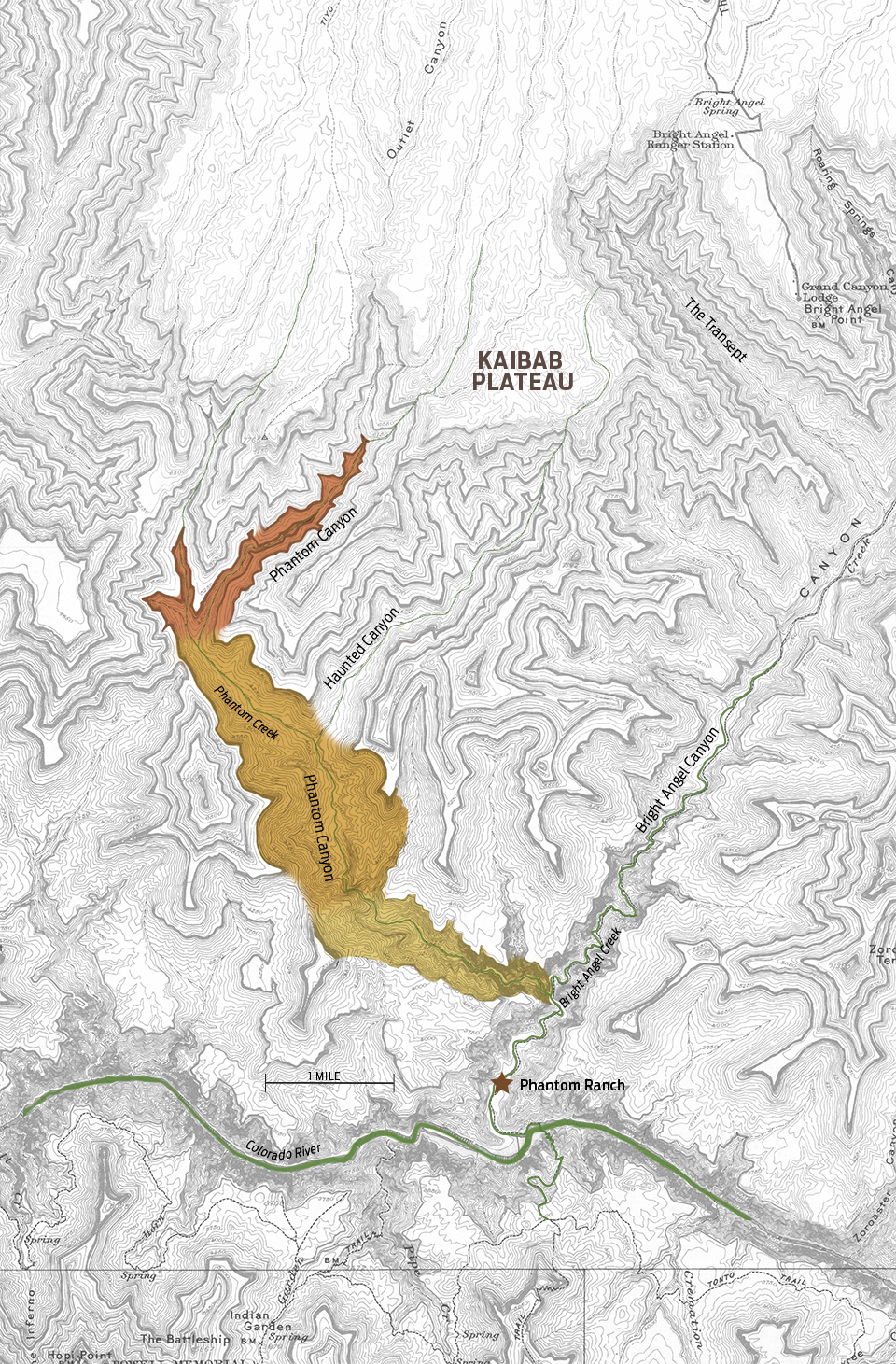

Where Phantom Canyon splits into two major feeder canyons, it is obvious that the flood came from the northeast. The western continuation of Phantom Canyon looks untouched, its trees still standing. Haunted Canyon, the northern addition, is heaped with debris. Roots swim to the surface of log piles.

I turn up Haunted and follow it.

I had made acquaintance with the storm that sent down this recent flood. At the time, I was in a canyon not far to the west of Phantom and Haunted when one of the largest floods I had ever witnessed came through. It grew from beneath a thunderhead after only two minutes of rain, sending boulders and entire trees through. I watched from a ledge, pinning my body against the cliff wall behind me.

A week later, I hiked to the Colorado River, the exit point for this flood. A raft group happened by in the evening, and we camped together. Three of the boatmen along were Pat Phillips, Bret Stark and a man called Okie. They each had been parked at Havasu Canyon the month before when their boats were blown end over end by a flood. We spent hours sharing stories.

When I mentioned seeing a large flood just a week ago, they all asked questions, curious about its size and the force. Stark asked if I was going to be walking along the river from here. I told him I hadn’t decided which way I’d go yet, but following the river was one of my thoughts.

“Why do you ask?”

“Well, if you’re down here,” he said, “keep your eye out. Phantom Canyon flooded, and they haven’t found one of the bodies yet. Sounds like it’ll show up in the river somewhere.”

“A week ago?” I asked.

“Seven days,” he said. “Probably the same storm system that flooded you. Friends of ours found one body near Tapeats Creek, and they tied her to shore so she wouldn’t float away.”

There was quiet for a bit. I looked out to the river. I had escaped the last storm so easily, climbing up to a ledge, my face finger-painted with flood mud, muscles shaking. To know that it killed people nearby did not change the water in my mind, but immediately I sensed my own breathing and the easy beating of my heart.

I looked back at Stark and asked, “So if I see a body floating down the river, you’re thinking I can somehow grab it?”

He gave me a grim smile. “No. I guess you just have to watch it go by.”

I decided not to follow the river. I did not want to stand helplessly, seeing a dead man come and go.

Traveling up Haunted Canyon for the next few hours,

I worked among the gaunt, broken remains of September’s flood. I ducked through the locked trunks of trees and ran my hands into gaping cavities in the ground where boulders were once planted. The eagerness of the flood had been replaced

by stillness.

Everything is waiting for the next thrust of motion. The violence is redeemed by today’s patience and placidity.

There is one place where cottonwood trees have been left in the form of a jungle gym dome. Out from under this dome comes a chant of canyon tree frogs. Their voices are each of a different tone, hard to tell how many, maybe 15 or 20. As if invited into a ceremonial hut, I crawl beneath the canopy into an open space, skirting over boulders. In the middle, the creek has pooled behind a dam of rock and wood. Bright purple flowers of western redbud trees float across the surface like Hawaiian leis. The edges of the pool are lined with silver-gray canyon tree frogs, each the size of a matchbook. They swell and collapse as they call, membranes around their throats pulsing outward.

The voices are percussion instruments, a mix of ratchets and marimbas. I listen to one, then another, each voice separated by octaves and half-steps. Put together, they produce a riveting drone. I crawl in closer. A few of the frogs shift uncomfortably. Others freeze. The noise goes on. They are basking in these new niches and enclaves left by the flood. For them, the flood is a blessing. Certainly, many were lost. But even that is a blessing, dissolving the glut of competition. I move forward just another inch. Too much, though. Frogs suddenly go catapulting every direction, slapping into the water. Their pale bodies plummet to the bottom, scooting beneath drowned leaves and branches. The place is suddenly quiet except for the trickle of water. Shadows drop through the flood debris over my head. Branches are interlocked like antlers. The flood isn’t gone. I feel it around me. The big water is gone, yes. But everything else is still here, every cataract and mood of the flood, every remnant of scale.

In the evening, I return and again fix my meal and carry it to the edge of the hole. Hours later I am still crouching, the canyon dark. There is not a single frog voice down there. It is clean. I stand and walk slowly around the deep chute. I squint to see down in the darkness. Is this a tomb, or is it the eye of a needle? This canyon will continue ushering floods for hundreds of thousands, even millions, of years. Undoubtedly, other people will die here. To call it a tomb, though, would be arrogant. This canyon predates the human species. Our lives here are as fleeting as the floods themselves.

The loss of life seems far away. Death is at the bottom of a hole that has no end as far as I can see, and I am at the top peering in. Even considering my experiences with floods, it is difficult for me to recapture the horror that must have been felt when people were in the pit of Phantom Canyon. The petrifying roar of trees, boulders and water compressed into an alleyway of rock seems unattainable right now. All I hear is the constant language of babbling stream water.

Part Two: September 11, 1997

The storm enters the Grand Canyon at a high butte called The Dragon. It breaks apart, sending itself out, lightning striking the points of rock that stand out of the Canyon like heaved idols. The storm overtakes a place called Shiva Temple, wrapping into an amphitheater canyon known as the Buddha Cloister. All of the names in this part of the Grand Canyon are theatrical. The landscape matches the names. Canyons engulf each other. On the opposite side of the Grand Canyon from Shiva Temple is a point called Mohave. The wind comes strong here, pushing away from the center of the storm. It is not raining on Mohave Point yet. A young German tourist stands on the farthest edge, watching the convulsions of clouds, how they fold into each other like tremendous, dark blankets. The force of the storm is palpable and mesmerizing. He sees rain in the distance. It comes in violet-colored sheets, swallowing the North Rim 14 miles across from him. The air smells rich with water. He has to spread his legs to stand against the wind. The ground vibrates. His skin prickles.

What he never sees is the stroke of lightning. It reaches clear across the Grand Canyon like an arm outstretched where there had been no arm before. It comes so fast that there is not even a flash registered in his eyes. The bolt of lightning strikes him directly, blowing him back from the edge. He lands on the ground, his body hitting like a sack of oranges. A woman standing behind him is also blown over, taking burns across her body.

When rescuers arrive, they find tourists administering CPR to the man. His heart is still beating, although his unconscious body shivers and charges from respiratory arrest. The woman is conscious. She has first- and second-degree burns. Attention is focused on the man. They hold a mask around his nose and mouth, forcing pure oxygen into his lungs. The rhythm of his breath slowly returns as they work. He will live.

Ken Phillips, the head of search and rescue for the Grand Canyon, is at the scene, lifting the man into a gurney. A tone comes across the radio on his hip. He reaches back and turns up the volume. Flash flood, the voice says. Phantom Creek. He looks up from the edge of Mohave Point. His eyes track across the Grand Canyon. On the other side from him, below the temples and spires, is Phantom Canyon. It is incised so deeply that none of it can be seen. Storms are plunging into it from the rims, arms of murky clouds reaching into every canyon that leads to Phantom. It looks as if a preposterously huge creature is sliding in. His first thought: Is anybody out there?

Indeed, there are people out there. A woman, her brother and her husband. With backpacks they had walked down to the popular Bright Angel Campground on the floor of the Grand Canyon. The couple, 39 and 40 years old, came on vacation from New Orleans for four days of foot travel through the canyons. The woman is a nurse practitioner and president of a hospice. Her husband is a police officer. The younger brother, studying to be a nurse practitioner, came from Chicago. He is in his mid-30s. They had set camp, spending their first night beneath stars and a clear sky.

On this, their second day inside the Grand Canyon, they get a late start, walking a northward trail until reaching the confluence of Bright Angel Creek and the narrow hall of Phantom Canyon. Phantom has a dark gravity to it that Bright Angel does not. Its black walls cut immediately out of view. It is as enticing as the devil peeking around a corner. Even with storms bearing down from the north, the sky directly overhead is fairly clear, sputtering out bits of rain now and then. Often the storms won’t come this low, sizzled away by the heat of the desert. Several thousand feet above the three of them, 2 inches of rainfall would be recorded for this day, while down here the gauges show barely a 20th of an inch.

They leave the trail and start up this inviting canyon whose head begins at 8,000 feet, where 2 inches of rain is now falling. Moving through clear, shallow water, a year-round creek sent from the North Rim, they splash up onto boulders and wade through crystalline pools. The flashing, orchestral tones of water draw them farther up the canyon.

It would be paradise, a muscle-relaxing, linen-clean scene for a Maxfield Parrish painting, except for the depth and claustrophobic squeeze of the canyon, except for the darkening of its stone, how shadows cast across each other. There is always a bit of fear in these canyons. The travelers drown it out as best they can. The youngest of the three goes ahead until reaching the glint of a clear waterfall. Sunlight breaks through clouds, leading down into the canyon. It is going to be a fine day, he thinks. Soon they will all three be here in the sun, mesmerized by the sweet spray of this waterfall.

He returns to the other two, offering a hand so that his sister can cross the boulders without getting too wet. He says that there is a waterfall up ahead. Beautiful. His hand goes out. He hears a deep-throated roar from the canyon behind him. At that moment his sister’s eyes dart upstream, held suddenly still. A word forms on her lips. Then she shouts it: “Water! WATER!”

He wheels around. Cresting over the top of the falls is something unimaginable. Like a wall of rust-red lava, a flash flood thunders down, consuming the entire waterfall. The space it occupies, the sound, the speed, the color, these are all impossible. A moment before was the sweet chime of a waterfall. Now they have no more than 15 seconds.

His eyes shoot downstream. The first instinct. Run. At a full sprint he could reach a clearing 50 feet away, a place where he could scramble to safety. But if he runs, what of his sister and brother-in-law? He glances quickly at the two of them, and their eyes are frozen. They seem no longer connected to their bodies. They are not going to run. In fact, if he doesn’t grab them out of their sudden stupor, they will be bowled end over end, no chance of survival. He is the one with outdoors experience. He knows that one should not freeze, that the deepest instinct, the one that says Move, is the only one to follow now. But if he leaves them here, they will die.

Ten seconds now. He yards back on his sister’s arm, shouting for her to move, to follow him. If they won’t run, they need to at least find protection. Eight seconds. There is a boulder nearby, about 8 feet tall, leaning against the canyon wall. He shouts again. “Get behind that boulder!” Their eyes turn to him as if just out of a dream, not yet awake. They almost float as they move, drifting without gravity. Seven seconds. He yells again, dragging them along. Six seconds.

They each crowd into the space, backing up to the boulder. Arms lock into arms, seeking protection. Three seconds. The sound rises like some godless creature. The young brother thinks, in that final moment, of dinosaurs. This, he thinks, is what it must have been like to have a Tyrannosaurus rex coming down on top of you. No way out. The thing is huge and angry. It has sabers for teeth.

One second.

“Please, God,” he says. “Please.”

The boulder shudders at the impact. It feels as if it might topple on them, 40 tons of rock turning over in the wall of a flood. But it does not come down. Like a huge ocean wave cresting with whitecaps, the flood wall passes. Water shoots through gaps behind the boulder. The slurry pounds over the top, twisting around on them. Currents immediately reel up their bodies chest-deep, pulling them apart. The boulder does nothing. There is no protection. The flood is everywhere.

He shouts instructions: “We’re going to get swept away! Keep your legs pointed downstream! Keep on your backs!”

But the other two do not hear him. Their eyes glaze in such a deep horror that their selves are gone, to who knows where. Somewhere safe and far away. He shouts again as the red water lifts, pulling him out from behind the boulder. He can barely get the words out now, “Save yourselves,” when the water has him. It sucks him into the flow. He tries to follow his own advice: Point his feet downstream to fend off objects. Float on his back so that his head can stay in the air.

None of this happens. He is taken straight to the bottom, his body no longer his own. His legs yank down, then behind him, rolling him over and over. The sound of the flood thrums underwater, the garble of furious air bubbles, barrels of air taken down with him. The canyon wall comes. He feels it. His body collides with it, rolling violently along its surface. Then something else. It is a boulder. A moving boulder. It rides up into his chest and he passes beneath it as if under a steamroller. Then the wall again.

Where is the air? He has not breathed for some time. His head surges out, and he catches a mouthful, breathing in mud and water and enough oxygen to keep him alive for a little longer. As he comes back down, a broken cottonwood tree thrusts into the right side of his head, sending him deeper.

He knows he is a good swimmer. He has performed well in triathlons in the past. There must be some way. But no matter how much force he commands of his body, he cannot muscle his way to control. He feels exhaustion setting in. The need for air.

Then he is out. A stray current sends him straight up, firing him like a missile. He is clear of the flood, completely above it. Flying. He takes a full breath. He can see the canyon walls around him. Cottonwood trees recoiling against the water. The sky. Freedom. But he sees all this for only that second. He falls from the air. Instantly he is down. He hits the floor of the canyon. There is gravel down here. The rocks are smaller, grating along the back of his head. He knows he is at the bottom.

By now the flood has carried him half a mile. He has taken only three breaths in this span. At the bottom he feels the ache. He must breathe. Soon his reflexes will take over for him. He cannot stop the urge to breathe. He will drown. Once he knows this, the flood pulling at his appendages, knotting them around each other because he has no resistance, he lets go. Death will come quickly, he thinks. And it is not so bad. He is a religious man. He has made his peace.

We fight so hard to survive. But to die takes this last, greatest strength. There is no terror now. He waits for it to come, the final gasp that will fill his lungs. He quietly ignores the pain and panic of his body.

Then he thinks of his wife. The pain and panic she will feel. His right hand hits something solid. It is not one of the many moving boulders. This one stays put. He catches a finger hold just as his body swings into an eddy behind the boulder. The water is shallow here. He figures he must be off to the side of the flood. He is face down. When he lifts his head, he finds air. He pulls it in, then coughs out red mud, his lungs seizing on him. A light current carries him along the shore of Bright Angel Creek. He has come into a calm area but hardly has the strength to clutch the young cottonwood trees going by, the shoots and elastic saplings. He finally gets a hold of one and pulls himself free.

He does not know what has happened. How can he know? Not more than a minute ago, he was reaching out to help his sister. He had been aroused by a sense of awe, the canyon huge around him, the beauty of a waterfall. Now here, suddenly, he slops his way into shallow mud. Where is his sister? She was in his hands moments ago. And his brother-in-law, there beside him?

The clear, tiny creek is gone. Now a tumultuous street of red water and mud rumbles through. Boulders detonate deep beneath. Objects become snared in rafts of debris, settling out in eddies as the flood moves down Bright Angel Creek, then on to the Colorado River.

Downstream from him, a torn piece of a blue waist pack snags against the shoreline. Just upstream is a blue sock and the broken frame of a pair of sunglasses. Much farther downstream is another blue sock, a pair of boxers, a yellow sandal, a white bandanna. The flood has riffled their belongings. It has searched their pockets, their gear, pulled their clothes off. Everything is left strewn and torn apart.

He is one of the pieces of debris. The silt has acted like sandpaper on his eyeballs. Now everything he sees is backlit by a halo. He crawls from the water to dry ground. He is bleeding. Any part of his body that stands out — ankles, shins, backbone, elbows, forehead, ears — is missing skin. The flood has tried to turn him into something else.

When he finds the strength, he stands. He knows that he is the sole survivor. His sister and brother-in-law are gone. He looks up into the hazy-bright sky through hundreds of scratches on his corneas. He is a Christian. He believes in God. And this God, he thinks, where was he?

“Where were you?” he demands. Then he throws his fists, tears coming out red with mud. “HOW COULD YOU DO THIS?” Mud streams down his face.

He begins to run, fumbles, almost falls, then runs faster. As he runs, he shouts at this God, hurling insults and incensed questions. He does not understand how this could happen. In the time of greatest need, God did nothing for them. Not for his sister, not for his brother-in-law. And what was this? Allowing him to live. Punishment? He screams at the sky. Furious. Out of control. He heaves his arms. He throws rocks, sticks. Over and over, “WHAT HAVE YOU DONE?”

After 20 minutes, he has no more energy to confront the heavens. He crumples on the ground. His first clear thought comes into his head. Not since he offered a hand to his sister, telling her of the beautiful waterfall just ahead, has his mind functioned in any customary way. He thinks that he should get up. He should find help.

Next, he is in a room. A helicopter has transported him to the South Rim only an hour after the flood. He knows he is the survivor. The only one. They do not need to tell him this. A desk is positioned strategically between him and a law enforcement official arranging paperwork. The survivor’s hair is matted with mud. Streaks of blood and abrasions cross his arms, chest and face. The more impressive wounds have been cleaned and bandaged. He does not fidget or look about the room. His vision is still cloudy. It has been, at the most, two hours since he was saved by the boulder and the eddy. Two hours since they died. He doesn’t have much sense of time.

The officer, wearing a tie and a badge, looks up at him, studying the pale, shocked complexion, the ghastly eyes. He has seen this too many times. A disaster, people dead, a bewildered survivor. He is almost angry that this has happened and at the same time unbearably saddened that he can do nothing and that he finds himself here in this role. He cannot shout or cry or run away. Strangers have died, he thinks. He controls his emotions, quieting himself so that he can gather the needed information — a technique common among those who must often deal with death. He says that he has a few questions. The survivor nods for him to go ahead.

“Whose idea was it to come here?”

“Mine,” he answers, his voice flat, the only voice he can offer.

“Had you been here before?”

“Yes.”

“And the other two had never been backpacking before?”

“Correct.”

“You were the trip leader?”

“Yes.”

“Did you know about flash flood dangers?”

“Yes.”

“How did you know?”

“People were killed in a canyon in Arizona. A couple weeks ago. I heard about it.”

“Did you think that there was danger in this canyon?”

“I thought there could be danger, yes.”

“Why did you go?”

The survivor pauses. His breathing is shallow. The event plays through his head with high volume. He can’t turn it off. He wonders: Did he kill them? Has he performed some terrible act? Or was it strictly the result of a flood? Was he an ordinary man thrown into an extraordinary circumstance, or was he a killer? He feels swollen muscles, a rash of sound, boulders crashing into each other like freeway impacts. But the room is quiet, fluorescent lights humming. He hears the crisp turn of a page under the officer’s fingers.

“I don’t know,” he says.

“You don’t know?”

The survivor swallows. “We were hiking,” he finally answers.

“Hiking?”

“Yes.”

“But in that narrow canyon, when a flash flood was coming, you must have had some idea.”

“I thought it could happen. Yes.”

“And you still went into the canyon. You knew you were putting lives at risk?”

“Yes. Am I in trouble?”

“I don’t know. That’s what I’m here to figure out. Why did you go into that canyon?”

“We were hiking.”

The officer takes a heavy inward breath, then lets it out. He draws his pen over the answers he has written down. “You were the trip leader,” he recites. “You knew about flash floods. You had been here before.”

“It was sunny,” the survivor says, partly in his own defense.

“Sunny?”

“Seventy-five percent clear, I think.”

“But you knew a storm was near.”

“Yes. I knew.”

Again, the hard breath of the officer. He has seen this before. So many times. Foolish people dying, getting people they love killed. For what? To go hiking? Drownings, rockslides, falls. He is even more inwardly angry now. He carefully holds down his emotions, the scientific, professional control he must maintain.

The evidence leads to only one place. The survivor sits and breathes into the pit of this realization. He has killed his sister and brother-in-law. He will someday, years away from this room, come to the conclusion that he is not a murderer, but for this moment he is sure that he is. All of his interior, emotional defenses have failed in this line of questions. He is finally broken.

The air stands taut between the two of them, a tight wire strung between human ignorance and the relentless happenstance of nature. Both the officer and the survivor struggle quietly with this division, while thousands of feet below them, miles away, the last of the floodwater trickles lightly from Phantom Canyon.