On a late afternoon in mid-November, the sun angles low over The Nature Conservancy’s Aravaipa Canyon guesthouse, lighting up a yellowing pecan tree like a flame. Below it, a dozen wild turkeys forage among lush foxtail grasses.

It’s hard to imagine this serene spot as the headquarters of a large ranching and farming operation. But it once belonged to the T-Rail Ranch, which employed as many as 20 permanent cowboys and controlled 5,000 head of cattle at its peak.

Farms and ranches such as the T-Rail contributed to the disappearance of turkeys in Aravaipa Canyon. Grizzly bears, wolves, bighorn sheep, pronghorns and beavers also disappeared. Today, reintroduced turkeys and bighorns once again populate the canyon, and much of its natural beauty has been restored, thanks, in large part, to The Nature Conservancy (TNC).

In 2016, TNC celebrated 50 years in Arizona. The organization’s work here began with the acquisition of the Patagonia-Sonoita Creek Preserve in 1966, although TNC did not have an official Arizona chapter until 1979.

In 1970, the Panorama Ranch on the west end of Aravaipa Canyon became the organization’s third Arizona project. Today, the group’s Aravaipa Canyon Preserve includes 9,000 acres of deeded land and grazing leases on another 44,000 acres, including the Bureau of Land Management wilderness area in the canyon itself.

The management of the preserve, whose early caretakers included author and naturalist Edward Abbey, provides a window into TNC’s work in the state, as well as its evolution — from an organization that bought and protected small parcels to one that works with partners to protect whole systems, even across international borders.

Aravaipa Canyon runs for 11 miles through the rugged Galiuro Mountains of Southern Arizona. Walls of volcanic tuff tower as high as 1,000 feet, cradling one of Arizona’s finest riparian woodlands, along with healthy populations of mountain lions, deer and javelinas.

One of Arizona’s few perennial streams, Aravaipa Creek is home to seven species of native fish, including two endangered species: the loach minnow and the spikedace. The trees that grow along its banks shelter more than 200 species of birds, including rare gray hawks, common black hawks and yellow-billed cuckoos.

At the peak of canyon settlement in the 1920s, about 700 people lived there. Large herds of cattle, goats, feral horses and burros browsed the canyon and tablelands. The T-Rail dominated the east end, where ranching and feed crops such as alfalfa dominated. The west end consisted largely of orchards.

The ecological effects were widespread. Farmers diverted the creek, miners dynamited fishing holes and harvested old-growth trees, goats competed with bighorns for food and habitat, and unrestricted cattle denuded native grasses.

Predator-control programs devastated populations of mountain lions, bears and coyotes. Fur companies solicited Aravaipa residents for pelts of raccoons, ringtails, bobcats and foxes, while farmers waged war on javelinas, rabbits and prairie dogs. Residents also harvested loach minnows to sell to fishermen and stocked non-native species in the creek.

Conservation efforts began in the 1940s, when Montana resident John Blackford launched a campaign to protect the canyon. He made a formal proposal to the National Park Service in 1952; the Park Service passed but recommended a nature preserve under TNC, the Wilderness Society or the National Audubon Society.

In the late 1960s, brothers Fred and Cliff Wood approached TNC about selling the group their 4,200-acre Panorama Ranch on the west end. There was no TNC field office, so a small operating committee led by conservationist Ted Steele led the effort. TNC made the down payment in 1970 but could not come up with the balance.

Steele also served on the board of Defenders of Wildlife, which received a timely bequest from the estate of California millionaire George Whittell. Steele convinced trustees to buy the Wood ranch, along with additional properties on the east end, including the McNair Ranch, formerly the T-Rail.

Meanwhile, in 1969, the secretary of the interior designated about 4,000 acres of public land inside the canyon as the Aravaipa Canyon Primitive Area. In the early 1980s, Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater led an effort to upgrade the primitive area to a wilderness area. That effort paid off in 1984 with the creation of the Aravaipa Canyon Wilderness, which today protects more than 19,000 acres.

Hunting and fishing were prohibited, and Defenders of Wildlife worked with the BLM to limit visits to the canyon, initiating the permit system that exists today. In 1988, Defenders of Wildlife transferred ownership of the Wood ranch and its other Aravaipa properties back to TNC and provided a $1.2 million endowment to manage them.

In 1972, Edward Abbey became the first manager of the Aravaipa preserve. Tasked with monitoring wildlife, patrolling the canyon and keeping hunters out, Abbey soon shared his job and salary with his friend Doug Peacock.

Working out of a trailer near the Wood residence, Abbey and Peacock filed reports to Defenders of Wildlife that included visitor numbers, wildlife counts (including what they believed to be two wolves) and Peacock’s observation that the human history of the canyon is “as colorful as a Western novel.”

It was Abbey’s first year-round wilderness job. He had just published Desert Solitaire, and at Aravaipa he recovered from a devastating romantic breakup and a period of writer’s block that lasted a year.

In June 1973, he wrote in his journal: “Still here! Longest I’ve held a steady job since … I was drummed out of the Army in ’47. Despite the lugubrious tone prevailing through most of these erratic journals, I am, most of the time, a rather happy man. … My mind is clear, my head on straight, my body functioning properly, my heart alive and throbbing — and them blues, they don’t come knockin’ on my door no more.”

Aravaipa provided the setting for some of Abbey’s most memorable essays, including the haunting story of his encounter with a mountain lion and a lighter essay about javelinas he titled Merry Christmas, Pigs! More importantly, he completed his novel The Monkey Wrench Gang, using Peacock as the inspiration for George Washington Hayduke.

While most of Abbey’s journal entries make no reference to time of day, the one for May 4, 1974, begins at 6:14:02 p.m.: “Currently on page 647 of Monkey Wrench. A splendid hilarious tragic book. … One-and-a-half chapters and an epilogue to go. Then FINIS.”

Defenders of Wildlife fired Abbey at the end of that month. He claimed in his journal that he had fallen out of favor with Steele. “A shabby, sneaky, cowardly thing to do,” he wrote of his dismissal.

But Abbey had not endeared himself to many Aravaipa residents. They objected to his habit of skinny-dipping in Aravaipa Creek. And his inflammatory letters to the editor didn’t sit well with the conservative ranchers, farmers and miners whose cooperation Defenders of Wildlife needed.

Historically, Aravaipa Creek rose from the ground as a visible spring. The emergence point has changed over time, fluctuating with natural cycles of drought and rain, and due to human-caused influences. Today, it emerges about a mile upstream from TNC’s guesthouse, amid towering stands of cottonwoods, whose tall, rough bark mixes with the graceful, pale trunks of sycamores.

Stamped with tracks of turkeys, javelinas, mountain lions and one of a handful of cows that have evaded capture, the creek’s beginnings are subtle, appearing first as wet sand with a few puddles, as though from a recent rain. A large puddle dappled with cottonwood leaves seems to ripple with a gentle current. But a closer inspection reveals water rising from the ground. From there, the flow quickly gathers into a recognizable stream. Under normal conditions, the creek flows through the canyon and disappears underground just beyond the west end. Protected along nearly its entire length, it has become one of the best native fisheries in the state.

Water has flowed like a perennial stream through TNC’s work in Arizona, beginning with its first purchase in Sonoita, then expanding to include projects along the San Pedro and Verde rivers. Preserving Aravaipa was also about preserving its creek, and the evolution of the preserve’s management illustrates how the organization’s mission has evolved and expanded.

“Historically, we were thinking about Aravaipa,” says Patrick Graham, TNC’s state director for Arizona. “Then we started thinking about the San Pedro River watershed [which includes Aravaipa Creek]. Now, we’re thinking about the Colorado River Basin.”

According to a TNC study, Arizona has already lost many of its rivers and streams. The 2010 study predicts that by 2050, if nothing is done, the state will lose seven more. That sense of urgency underlies TNC’s evolution.

“Buying land and protecting it was not going to be enough,” Graham says. “We couldn’t acquire enough of it fast enough to really make a difference. Maybe this is the big challenge: How do we take these ideas and scale them up large enough, fast enough, before our rivers go dry?”

Broad, flat Aravaipa Valley spreads out over the aquifer that feeds Aravaipa Creek. A little upstream of today’s emergence point, the water lies just close enough to the surface to maintain young cottonwoods that line the edge of a grassy pasture.

On this fall day, the meadow — part of the Cobra Ranch before it was donated to TNC — vibrates with life. The clacking of grasshoppers accompanies the trill of Cassin’s sparrows. A vermilion flycatcher abandons its barbed-wire perch just long enough to snatch its prey before returning to its post. A breeze ruffles the tawny grasses: fluffy-headed beardgrass, tall-bunched sacaton, sparkler-like spangletop.

“When we first got the Cobra Ranch about six years ago, this had been abandoned as a farm and they fed cows here,” says preserve manager Mark Haberstich. “There was no grass, mostly dirt and a lot of erosion. Historically, it was probably a bigger, marshier, grassier area, and one of the key species of the flood plain is sacaton, so I started planting it.”

Transplanting seeds germinated in a greenhouse, Haberstich initially watered the field with flood irrigation to mimic historical flood cycles. He also planted a variety of other native grasses. “I’ve got five years into this, and it’s getting progressively better,” he says.

Haberstich harvests the grasses to restore the preserve’s historical grasslands — he spreads it as mulch or feeds it to cattle, which pass the seed along with fertilizing manure. He thinks of it as a working laboratory, and that’s one way the Aravaipa preserve has evolved to contribute to the organization’s new business model. “If I can demonstrate sustainable, human-based strategies that contribute to the preservation and conservation of a watershed, that information can be used on a bigger scale,” he says.

He also partners with organizations such as the Arizona Game and Fish Department, in harvesting Aravaipa’s native fish to help restock other rivers, and the BLM, in setting prescribed fires to improve habitat for reintroduced bighorns. Over the two decades he’s worked in the preserve, Haberstich has seen many historical conditions restored, including swampier areas that now support lowland leopard frogs.

“It’s been neat to see the whole process,” he says. “Most of the really big threats, like water, have been, for the most part, taken care of. Acquiring the lands, we have solved a lot of problems.”

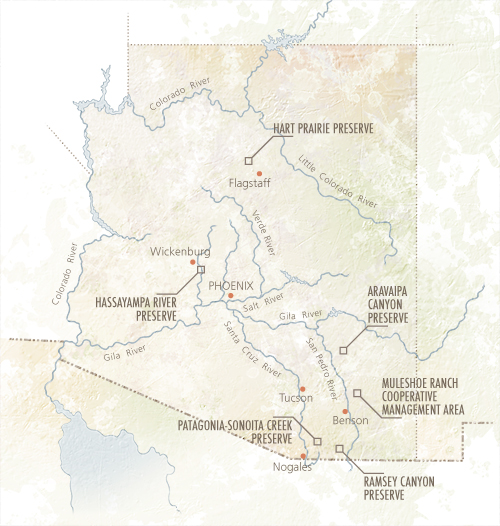

The Nature Conservancy in Arizona

The Nature Conservancy is a leading conservation organization that works locally, with global reach, to protect the state’s fresh water, forests, critical lands, wildlife and rich biodiversity. 2016 marked TNC’s 50th anniversary in Arizona.

PRESERVES TO VISIT

Aravaipa Canyon Preserve

The perennial Aravaipa Creek flows through this preserve’s namesake. The 11-mile-long gorge is home to mountain lions, deer and javelinas, along with seven species of native fish. Access to Aravaipa Canyon from the preserve requires a permit from the Bureau of Land Management.

Directions (to west end of preserve): From Tucson, go north on Oracle Road (State Route 77) for 18 miles to a “Y” intersection in Oracle Junction. Bear right to stay on SR 77, then continue 35 miles to Aravaipa Road. Turn right onto Aravaipa Road (which turns into a gravel road) and continue approximately 12 miles to the preserve.

Information: Aravaipa Canyon Preserve, www.nature.org/aravaipa; Bureau of Land Management, 928-348-4400 or www.blm.gov/az

HASSAYAMPA RIVER PRESERVE

Rare Gilbert’s skinks can be found in this preserve, as can many other species of lizards. Palm Lake, a 4-acre pond and marsh area, provides a habitat for the endangered Southwestern willow flycatcher and hundreds of other bird species. The preserve’s operating days and hours vary depending on the season.

Directions: From Wickenburg, go southeast on U.S. Route 60 for 3 miles to the preserve, which is on the west side of the road near Milepost 114.

Information: Hassayampa River Preserve, 928-684-2772 or www.nature.org/hassayampa

Muleshoe Ranch Cooperative Management Area

This area’s seven perennially flowing streams represent some of Southeastern Arizona’s best remaining aquatic habitat. The site is jointly managed by TNC, the Bureau of Land Management and the Coronado National Forest. Visitors can stay overnight in one of five casitas (reservations required).

Directions: From Willcox, go west on Airport Road for 14 miles to a “Y” intersection. Bear right onto Muleshoe Ranch Road and continue approximately 14 miles to the preserve.

Information: Muleshoe Ranch Cooperative Management Area, 520-212-4295 or www.nature.org/muleshoe

Hart Prairie Preserve

Home to uncommon wildflowers, ponderosa pines, elk, birds and the world’s largest community of Bebb willows, this preserve offers a cool getaway at the foot of the San Francisco Peaks, Arizona’s highest mountains. TNC hosts 90-minute nature walks every Sunday from mid-June through September. Other visits are by appointment only.

Directions: From Flagstaff, go northwest on U.S. Route 180 for 9.5 miles to Forest Road 151 (Hart Prairie Road). Turn right onto FR 151 and continue 4.5 miles to the preserve, on the right.

Information: Hart Prairie Preserve, 928-774-8892 or www.nature.org/hartprairie

Patagonia-Sonoita Creek Preserve

This preserve protects some of the largest Fremont cottonwoods in the United States, and rare plants found in the Sonoita Creek watershed include Huachuca water umbels and Santa Cruz beehive cactuses. A diverse avian population makes this a popular spot for birders in spring and summer. The preserve is open Wednesdays through Sundays, and a small fee is required.

Directions: From Patagonia, go southwest on Pennsylvania Avenue, which turns into Blue Heaven Road, for 1.5 miles to the preserve’s visitors center, on the left.

Information: Patagonia-Sonoita Creek Preserve, 520-394-2400 or www.nature.org/patagonia-sonoita-creek-preserve

Ramsey Canyon Preserve

The lush Ramsey Canyon is a world-renowned hot spot for birders, and 15 hummingbird species have been spotted there. The preserve’s boundaries include plant communities ranging from semi-desert grasslands to pine-fir forests. It’s open Thursdays through Mondays, and visitors must pay a small fee.

Directions: From the intersection of state routes 90 and 92 in Sierra Vista, go south on SR 92 for 6 miles to Ramsey Canyon Road. Turn right onto Ramsey Canyon Road and continue 3.6 miles to the preserve.

Information: Ramsey Canyon Preserve, 520-378-2785 or www.nature.org/ramsey

For more information, call The Nature Conservancy at 602-712-0048 (Phoenix) or 520-622-3861 (Tucson), or visit www.nature.org/arizona.