These days, a cross-country flight doesn’t usually make news, but in the early 1920s, America was still getting acquainted with air travel, and the idea of mailing a letter in New York and having it arrive in San Francisco in an airplane was hard for many Americans to comprehend. On December 31, 1920, John Goldstrom, a reporter for what then was called The Arizona Republican, set out to demystify the process by mailing a valuable parcel — himself — from coast to coast.

“If you are one of the hundreds of thousands who have sent letters by air mail in the past year, you’ve probably wondered as you’ve dropped your mail in the box: ‘How much quicker will it be delivered?’ [or] ‘Will it be delivered at all?’ ” Goldstrom wrote. “Speed and safety — these are the goals of the air mail service.”

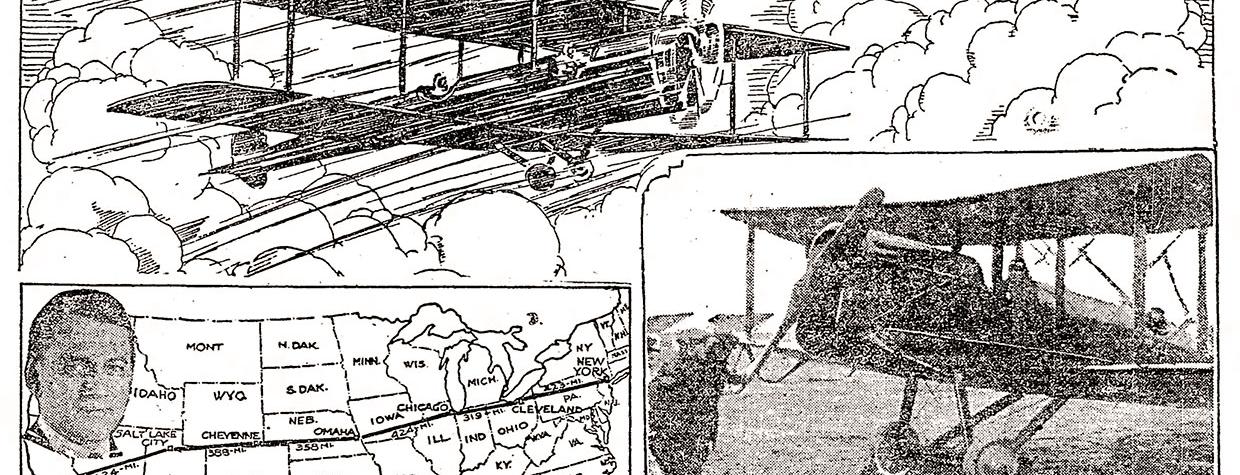

But speed and safety are relative concepts. The first leg of the trip, from New York to Cleveland via biplane, took more than five hours to cover 440 miles in subzero temperatures. From there, Goldstrom continued west, stopping in cities as big as Chicago and as small as North Platte, Nebraska. The approach to the latter was rough, he recalled: “We fly into the face of a 40-mile gale, which soon lashes itself into a 60-mile hurricane. We toss about in the Nebraska plains like a cork on the winter Atlantic.”

Over the Rocky Mountains, Goldstrom experienced more turbulence, and this time, it was enough to spin the plane “in a way that makes me fear not so much that we will crash as that we will not crash hard enough.” He and his pilot did crash but were uninjured, and after repairs, they continued to Salt Lake City. But another crash, near Elko, Nevada, left them stranded in the desert during a dust storm before being rescued.

Finally, on January 13, 1921, Goldstrom arrived in San Francisco after an air journey of some 2,600 miles, covered in about 34 hours of flying time. “The Golden Gate never has looked more golden than it does after the 13 days, 6 hours and 35 minutes of transcontinental endeavor,” he wrote.

The intrepid reporter had lost 20 pounds and survived two crash landings — and letters he’d mailed by train had beaten him by more than a week — but he proclaimed the trip a success. With more stations, better planes and more money for pilots and mechanics, Goldstrom wrote, it would become possible to deliver mail from coast to coast in 48 hours or less. It took a while, but history proved him right.