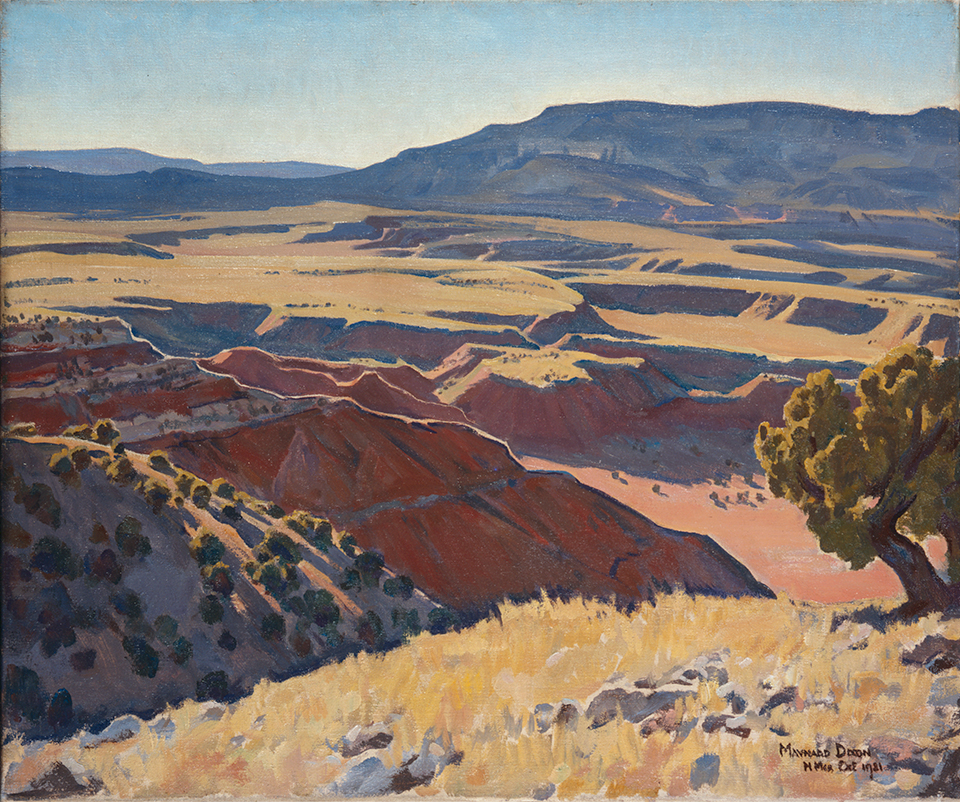

Thomas Moran, Gunnar Widforss, Bruce Aiken, Ed Mell ... some of the country’s most renowned artists have offered their visual interpretations of the Arizona landscape. Among that elite group is Maynard Dixon, who is considered the master painter of the Southwest. The story of his life is pretty impressive, too.

By Kelly Vaughn

It is a summer day in Columbus, Ohio, in 1999, and the woman stands with her arms clasped loosely in front of her. She wears a black long-sleeved shirt and khaki shorts. Her hair is bright blond and pulled back with a black butterfly clip. She is anxious, but not overly so. Her posture never varies.

In front of the woman stands Nan Chisholm, a New York-based art expert, and before her, on a big wooden easel, is an original Maynard Dixon oil painting titled I Looked on My Valley and It Was Beautiful. It shows a man in profile, looking out into a great gray landscape, his own clothes painted in muted tones to complement the rock on which he’s sitting. He wears a brown hat. A gun is holstered at his hip. His boots are laced to mid-shin. The painting dates to San Francisco, circa 1912. It has been handed down over generations in the blond woman’s husband’s family.

This segment of Antiques Roadshow is only two minutes and 15 seconds long, but there is a sense of a looming climax — that when Chisholm tells the blond woman how much this painting is worth, there will be awe, crying, whooping, jumping.

Instead, the woman coolly says, “Well, isn’t that something?”

Chisholm valued the Dixon between $20,000 and $30,000 if it were to go to auction. Upon reappraisal in 2013, it had grown in value — to somewhere between $150,000 and $250,000.

That is something. But it’s no real surprise, either. Dixon was, after all, the consummate painter of the American West.

Early Promise:

San Francisco to New York

Unpacking Maynard Dixon feels a lot like wading into very deep, very wide water. There are plenty of stories. Hundreds of documents. Experts galore. Paintings and quotes and letters and interviews. Legend and lore repeated time and again. Waves of images. But we can’t talk to the man himself — he died in 1946. Instead, we hope to hear his voice through his paintings, and through the legacy contained therein.

Born in Fresno, California, in 1875, Dixon was the only child of Confederate veteran Harry St. John Dixon, an attorney, and Constance Maynard Dixon, the daughter of a Navy officer from San Francisco. From his mother, Dixon learned an appreciation for classic literature and drawing. From his father, he “absorbed … strict standards along with a family culture based on the code of honor of the Southern aristocracy,” writes Dixon scholar Donald J. Hagerty in A Place of Refuge: Maynard Dixon’s Arizona. “For Dixon’s father, it was the ‘damn Yankee.’ For Dixon, it [eventually] became the ‘damn businessman’ or the ‘damn smart-arty artists,’ those who ran with whichever style was in vogue.”

Prone to bouts of frailty because of his severe asthma, Dixon spent a fair amount of time inside the family home: sketching the lines of the San Joaquin Valley, creating illustrations for the scenes he read in novels, using local cowboys and cattle as the subjects for his early portraits. By the time he turned 16, he’d grown some confidence, too, and mailed two of his sketchbooks to acclaimed Western artist Frederic Remington. The response was both encouraging and cautionary.

“You draw better at your age than I did at the same age,” Remington wrote. “If you have the ‘sand’ to overcome difficulties, you could be an artist in time. No one’s opinion of what you can do is of any consequence — time and your character will develop that. … Art is not a profession which will make you rich, but it might make you happy — its notaries are all sacrifices, but you are the master of your own destinies. Another thing — never cheapen yourself — you do not know it, but to be a successful illustrator is to be fully as much of a man as to be a successful painter, so I do not think many young men help themselves financially in that way. If you want to get a living while studying, that is very hard — it can be done, but circumstances, and not men, are responsible.”

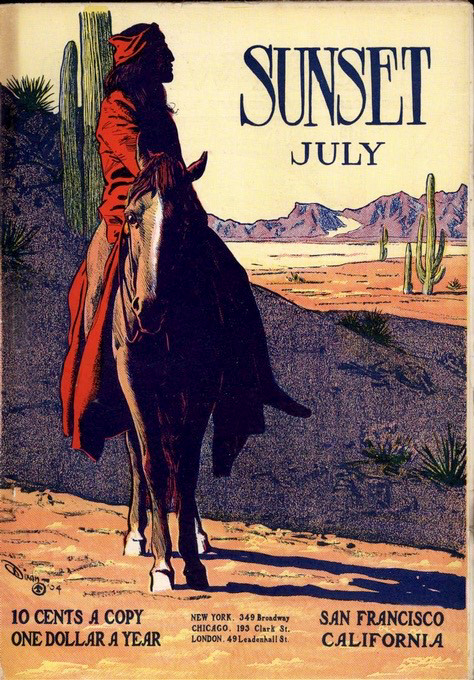

Two years after his correspondence with Remington, Dixon moved to San Francisco to attend the California School of Design. But after three months of studying there, he quit, determined to pursue an education on his own. He jumped into the world of illustration with both feet, publishing a series of sketches in Overland Monthly in 1893. By 1902, his work was appearing in Sunset magazine.

Two years after his correspondence with Remington, Dixon moved to San Francisco to attend the California School of Design. But after three months of studying there, he quit, determined to pursue an education on his own. He jumped into the world of illustration with both feet, publishing a series of sketches in Overland Monthly in 1893. By 1902, his work was appearing in Sunset magazine.

“I would call the years between 1893 and 1912 Dixon’s ‘illustration period,’ ” says Mark Sublette, a Dixon scholar and the owner of Tucson’s Medicine Man Gallery and the Maynard Dixon Museum, home to approximately 150 Dixon works. “He was highly successful and moved to New York after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.” Indeed, the earthquake so decimated the city that Dixon had little choice but to leave. New York, it seemed, would be his best bet in terms of marketing his art.

From there, his illustrations appeared in magazines, in national ads and even in a number of books. And Dixon’s artistic circle was growing. In the Big Apple, he worked and socialized with painter Robert Henri, who led the Ashcan School artistic movement. And when he could, he visited the city’s innumerable museums, studied American art and practiced his own easel painting.

But in 1912, dismayed by commercial depictions of the American West, Dixon returned to San Francisco with his wife, Lillian West Tobey, and their young daughter. He opened his studio at 728 Montgomery Street, in a three-story brick building that dates to the early 1850s. The building was severely damaged during the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake but has since been restored and reopened with commercial and living space. The building has been on the San Francisco Planning Department’s dedicated landmarks list since 1969, and it was within its walls that Anita Baldwin — the daughter of mining magnate E.J. “Lucky” Baldwin, and one of the wealthiest women in America — commissioned Dixon to paint four murals in her new home, Anoakia, in Arcadia, California.

The gig changed Dixon’s life. The murals’ subjects were Plains Indians, and their significance was immense. “He’s written up in the Los Angeles Times,” Sublette says. “He gets rave reviews, and now he has this benefactor in Baldwin.”

By his own account, Maynard Dixon was no longer just an illustrator: “As a painter, then, I date to 1912.

Arizona: East to See the West

Of course, Dixon had been painting all along, but now, it seemed, he had a renewed sense of purpose — and much of that was focused on documenting the West. In 1900, inspired by friend and mentor Charles Lummis to “go east to see the West,” Dixon crossed into Arizona Territory for the first time. His first stop was Fort Mohave, where he immediately endeared himself to the people who lived there: sketching their portraits, hearing their stories, giving them 25 cents in turn.

His travels next took him to Prescott, where he met with poet Sharlot Hall, then on to Jerome. He hiked to the ruins of Montezuma Castle, near Camp Verde, before making his way to Phoenix — the capital of the Territory, with a population of 5,000.

“Attracted by Arizona’s Hispanic culture, he moved on to Tempe, creating numerous drawings of Mexican laborers and their residences,” Hagerty writes. “Dixon stayed in their homes, enjoying the hospitality, and in the starlit evenings the people taught him to sing Spanish songs.”

In a letter he sent to writer Elwyn Hoffman, Dixon reflected on the adventure: “For me it has been for the past two months a checkered layout of Indians, cactus, rocks, sunlight, antiquities, mesas, Mexicans, adobes, Spanish songs — and salt pork.”

Over the next decades, Dixon returned often to Arizona, including during a 1902 Santa Fe Railway commission he accepted. During that trip, he traveled to the Hopi villages of Oraibi, Polacca and Walpi, where he sketched the people, their gardens, their shelters and more. In late August 1902, he traveled by freight wagon to Ganado, where he met trader John Lorenzo Hubbell. The two became fast friends, and Dixon’s visit lasted two months. After his departure, he and Hubbell corresponded until the latter’s death in 1930.

As much as Dixon admired Hubbell, he fell in love with the landscape of the Navajo and Hopi nations. His journal reveals the depths of that affection.

“On the map of Arizona, Navajoland appears as a great empty place, decorated with a scattering of curious names: Jeditoh Springs, Skeleton Mesa, Canyon del Muerto, Aga-thla Needle, Nach-tee Canyon, Monument Valley, the Mittens, Pei-ki-ha-tsoh Wash — all hinting at a far strangeness,” he wrote. “A vast and lonely land it is, saturated with inexhaustible sunlight and astounding color, visible with unbelievable distinctness, and overspread with intense and infinite blue. Its long drawn levels are a setting for the awesome pageant of gigantic storms advancing under sky-built domes of clouds, trailing curtains of rain and thin color-essence of rainbows.”

He painted the landscapes of Northeastern Arizona with the same sort of poetry we find in his writing about the place, and he returned often to its themes. In 1912, the National Academy of Design accepted his The Trail to Pei-ki-ha-tsoh in its annual exhibition, and in the years that followed, Dixon generated countless paintings of the Navajo and Hopi people he met.

“He had a real love for these people,” says Kenneth Hartvigsen, the curator of American art at the Brigham Young University Museum of Art, which maintains an extensive Dixon collection. “That’s part of what makes him so special. He was an outsider. He had to travel to visit, and he did it in a way that feels personally authentic. His creative inventions came from a place of support and love.”

“He had a real love for these people,” says Kenneth Hartvigsen, the curator of American art at the Brigham Young University Museum of Art, which maintains an extensive Dixon collection. “That’s part of what makes him so special. He was an outsider. He had to travel to visit, and he did it in a way that feels personally authentic. His creative inventions came from a place of support and love.”

On some level, too, Dixon may have been trying to make amends for work he did as an illustrator for books and advertisements. Some of that work played into the stereotypes of the American West that capitalized on cultural insensitivity; later in his career, Dixon sought to dispel those stereotypes.

Another trip to Arizona, in 1915, would mark the beginning of a shift in Dixon’s painting style, as well as the beginning of the end of his first marriage. The family began their journey in Tempe, staying for two weeks while Dixon’s wife and daughter acclimated. From there, they went to Globe, then Holbrook to meet with Hubbell. Finally, they moved on to Flagstaff and the Grand Canyon.

Surprisingly, Hagerty writes, the latter proved only mildly inspirational: “Dixon made a few half-hearted oil sketches and drawings there, but the large numbers of tourists dampened his desire to paint. More likely, he felt the Grand Canyon was not sufficiently remote or isolated enough for his purposes.”

Ultimately, Dixon produced about 30 landscape sketches on the trip, along with handfuls of drawings and at least five large canvases. He was exploring impressionist colors and incorporating other techniques he’d seen on display earlier that year at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, a show in which one of his three entered pieces received a bronze medal. He was, it seemed, both energized and exhausted.

After the trip, however, life in San Francisco would be difficult. His wife fell deeply into alcoholism, struggling for another two years until she and Dixon divorced in 1917. Broken by the loss of his family, Dixon traveled to Montana on a commission from the Great Northern Railway, then accepted a position with outdoor advertisers Foster & Kleiser.

He wouldn’t return to Arizona for five years.

The Great Depression:

Breaking the Man

“The West lends itself to a romantic, symbolic network of ideas,” Hartvigsen says. “Dixon was trying to find himself, but he was also trying to find the truth in these places — and our truth in these places. He was in service to us, to discover what these landscapes feel like and mean to us. The landscapes pushed him away from illustrations because he realized there were truths to be found. Still, we have to search for them and be engaged with them.”

We feel that search in Dixon’s poetry, in references to “the dim and wandering ghost of wilderness tribes disappearing into the blue and empty ether.” We see it in the paintings he produced between 1915 and 1920, too, and again in those he created between 1920 and 1931, an era Sublette refers to as the artist’s “cloud period.” In this body of work, many of the skies he painted are ripe with white and gray harbingers of shade and rain. Evening and Afterthought is an example; Cloud World is another. Moonrise Over the Desert is more subtle. In all of them, there is a sense of inherent admiration for the unbroken expanse of the American West. A longing to be there again.

That opportunity came to Dixon in 1922, when he and his second wife, photographer Dorothea Lange — they married in 1920 — crossed the California-Arizona state line, making the long journey to Kayenta at the invitation of John Wetherill. They stayed for four months, traveling deep into the backcountry of Navajoland — to places such as Tsegi Canyon, Betatakin, Black Mesa, Monument Valley and the long sandstone reaches of the spaces in between.

Another trip, in 1923, this time with Baldwin and Lange, resulted in another lengthy stay. According to Hagerty, “Baldwin’s camping equipment was outrageous, Dorothea thought — ten tents shaped like Chinese pagodas, with the food mostly in cans, including caviar. Reluctantly, Lange served as camp cook, preparing meals for Dixon, Baldwin, her bodyguard and two drivers. … When Walpi’s annual Snake Dance commenced, tourists who came to see the event clustered around Baldwin’s luxurious, incongruous encampment. Dixon shunned the crowds, enjoying the hot August winds sweeping over the mesas with the drama of sailing clouds bringing the promise of rain.”

Even after the women left, Dixon stayed on, living for another four months with Namoki, a Hopi snake priest and elder, and Namoki’s brother, Loma Himma, drawing scenes from their daily lives. Dixon returned to San Francisco with his sketchbooks full. Many of his cloud paintings originated from those pages, as did stunning portraits of the Navajo and Hopi people he encountered during the visit. Twelve of his Arizona paintings were put on display at New York’s MacBeth Gallery.

“Dixon had really beautiful, sensitive treatment of figures,” Hartvigsen says. “While he’s best known for his landscapes — and his landscapes are astounding — he really did have a sense of the human form and of capturing the personality of the sitter.”

“Dixon had really beautiful, sensitive treatment of figures,” Hartvigsen says. “While he’s best known for his landscapes — and his landscapes are astounding — he really did have a sense of the human form and of capturing the personality of the sitter.”

And it seems the Hopi way was fully imprinted on Dixon by the mid-1920s. Lines from his poem Little God reveal the depth of his admiration for the people and their practices

So — you fooled me little Katchina, did you?

Strange little terrible tufted god,

inscrutable small symbol of old mysteries,

painted, grim-visaged, austere,

enigmatic behind your savage green mask,

hanging there on the pearl-white earthen wall, —

so — you eluded me, did you?

Yes, — but already I have charted the theme:

the long step-down pattern of rectangular mesas,

the dreaming three-domed symbol of thunder clouds,

the mystical slow growing of tasseled corn.

I will draw forth the ghosts of your cliff-swelling fathers,

I will conjure old Betata Kin back to life,

and in my visions will live again Kit Seel and Sikyatki.

I will yet somehow divine your mysterious meaning.

Look out, little Katchina,

bright painted small inscrutable god,

perhaps I shall more than half know you.

In ways, Dixon did divine the mysteries of the Hopi Tribe when he returned to San Francisco, painting even more portraits of the friends he made there.

“He really does some great work [in] 1922 and 1923,” Sublette says. “And I think that in 1927, he had something like 18 museum shows across the country. Then, of course, he gets the commission to paint the mural inside the [Arizona] Biltmore hotel in Phoenix [see The Paintings on the Wall, page 46]. Just as he finishes that, the stock market crashes and the country descends into the Great Depression.”

So, too, did Dixon.

“Everything went downhill for him in terms of sales,” Sublette says. “Over the next five years, he only sells a couple of dozen paintings.”

Financially strained and creatively frustrated, Dixon, Lange and their two sons, Daniel and John, once again went east — this time to Taos, New Mexico, where they stayed for seven months in 1931, living in a home loaned to them by Mabel Dodge Luhan. “Well, if I can drag it out here until Christmas, I might show something myself — though it will be hell trying to out it,” Dixon wrote to his friend Harold von Schmidt. “Other than financially, we are going fine and wish you the same.” It was a critical time in the artist’s career, but he came out of it with a series of paintings that were extraordinary, according to experts.

“He creates some fantastic paintings in New Mexico,” Sublette says. “This would be yet another great period for him. But as he and Dorothea are driving back to California with the boys, they’re seeing the great exodus of people — the Okies — migrating west for opportunities, and it really strikes him. At this point, Dorothea starts to get involved with social causes and understanding.”

Dixon did, too, by default — Lange’s White Angel Breadline photograph, which dates to 1933, catapulted her into the national conscience, and she became the most well-known documentary photographer of the era.

In the years that followed, Dixon was immersed in painting the everyday people he encountered on the streets of San Francisco. The colors he chose were darker, more muted. The lines he used resembled the lines of Lange’s photographs. Their subjects were similar, too — picketers, dockworkers, maritime strikers, the homeless. In 1934, he was awarded a Public Works of Art Project grant to document and paint the construction of Boulder Dam (now Hoover Dam) on the Colorado River at Black Canyon.

“He’s there for a month,” Sublette says. “In that time, five men die. The hospital’s full. He sees his brother-in-law — a really bright, educated, erudite guy — is down to doing physical labor. Dixon really starts to wonder what this country had come to.”

“He’s there for a month,” Sublette says. “In that time, five men die. The hospital’s full. He sees his brother-in-law — a really bright, educated, erudite guy — is down to doing physical labor. Dixon really starts to wonder what this country had come to.”

In his own reflection on the project, Dixon wrote: “I found there a dramatic theme: Man versus Rock; the colossal dam an immense work compared to man, but a peanut compared to its setting. A bewildering display of engineering for the understanding of which I had not the least preparation in past experience. It gave me an impression of concealed force — and of ultimate futility.”

The paintings Dixon created during the Great Depression speak overwhelmingly to that theme. Shapes of Fear is a drab tableau of faceless characters huddled together in robes — an expression, Sublette says, of Dixon’s own fears about the Depression. In No Place to Go, we see a man in work clothes with a pack strapped to his back. He is backed against a wooden fence, with nothing but rolling hills and the ocean behind him — everything in shades of brown, blue and gray. Forgotten Man served as the thesis for Dixon’s Forgotten Men series.

“That painting, in particular, really shows a direct tie between Lange’s photography and Dixon’s own work,” Hartvigsen says. “The angle is very, very similar to the White Angel Breadline photo. And I think there were times during the Depression where he saw himself in some of those men. He thought, That could be me. There’s a period here where they really had very little.”

Dixon’s own records indicate he created 282 pieces between 1930 and 1935, the year he and Lange divorced.

To Tucson: For Good

Edith “Edie” Hamlin had high cheekbones and long eyelashes, but — more importantly to Maynard Dixon — she was an artist, too, painting the West in a way all her own. And she loved him. Despite a 30-year age difference, they married in 1937.

The same year, Herald R. Clark, the dean of BYU’s College of Commerce — there was no art school at the university at the time — approached Dixon, having seen some of his social realism paintings in a St. Louis newspaper. The men struck a deal: Clark would purchase 85 pieces for $3,700, forming the basis of the university’s art collection.

“Dixon, of course, wanted to seal the deal with a toast,” Hartvigsen says. “Clark, being a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, declined. So, they sealed the deal over a shot of milk.”

Financially secure for the first time in years, the Dixons moved to Tucson in 1939, splitting their time between 2 acres on Prince Road and their summer home in Mount Carmel, Utah [see Maynard Dixon Legacy Museum, page 34]. Dixon was aging rapidly, his lungs rattled by the cold winds of San Francisco and emphysema from years of smoking hand-rolled cigarettes.

Tucson, it seemed, made Dixon feel lighter somehow, as he reveals in his poem Sun-Land:

… I feel the inescapable pull of the earth, —

the deep old Earth pulling me back to her.

But now as the changeable colors of days

wheel with increasing velocity past my sight

these eyes of mine grow steadier,

my heart grows stronger,

and from the deep old Earth I know knowledge of things,

wonderful things I could never have known before;

and yet — where is the vast arc and the rainbow edge of the dream —

that marvelous Dream —

I could never have dreamt, except —

except in the Sun-Land.

During the early 1940s, the couple traveled throughout Arizona and hosted a number of friends and contemporaries — including photographer Ansel Adams — in their Tucson home, an ochre-colored adobe with a thunderbird emblem emblazoned on its address plaque and a single cottonwood near the patio. The tree began to appear in many of Dixon’s paintings.

During the early 1940s, the couple traveled throughout Arizona and hosted a number of friends and contemporaries — including photographer Ansel Adams — in their Tucson home, an ochre-colored adobe with a thunderbird emblem emblazoned on its address plaque and a single cottonwood near the patio. The tree began to appear in many of Dixon’s paintings.

“He knew its leaves, rotating and rattling, might foreshadow the arrival of rain,” Hagerty writes. “When enough frosty nights prevail in autumn, the cottonwood’s foliage turns from bright green to shining yellow, the spade-shaped leaves like little mirrors throwing shimmering light on the adjacent terrain. The tree is often solitary, tolerating little between it and the sun and wind, as did Maynard Dixon, who made it a personal symbol in many canvases.”

By 1945, though, the artist was collapsing, tied constantly to an oxygen tank. Still he painted.

“To those who saw him then, he appeared a lean, weathered man with drooping mustache and chin beard, sketchbook and pencil always clutched in his left hand,” Hagerty writes. “But those who looked closely saw that his blue eyes still incessantly searched the desert horizon.”

On November 13, 1946, Hamlin found Dixon unconscious in his wheelchair. He died a few hours later. His ashes went to live in a Hopi bowl he’d brought back from Walpi in 1923. Hamlin returned to San Francisco in 1953 and worked to preserve Dixon’s legacy until her own death in 1992.

It isn’t easy to articulate that legacy, and it can’t simply be explained by the value of Dixon’s paintings today — the “Well, isn’t that something?” aspect of it all. Dixon’s paintings are a testament to the romance of the American West and its people.

“When you talk about ‘the West,’ you almost always want to talk about the Old West,” Hartvigsen says. “The Hollywood cowboy and Indian stories. You have the essentialist narrative of the Native peoples as being these perfect societies that had no strife. I think that Dixon, while very much part of that and being inspired by that, was always digging and drilling down to find something real. I think he was trying to find himself and a place where he felt comfortable and safe and protected, and the landscape of the West provided that for him. That’s his legacy. As much as there is a process of imagination with him, it was in service of finding the truth of the American West.”

To learn more about Maynard Dixon and to see more of his art, subscribe to our digital edition today for immediate access to the September issue of Arizona Highways.