Laura Gilpin was born on the north side of Colorado Springs, Colorado, in 1891. At an early age, she was drawn to photography. Her father, perhaps glimpsing the talent she’d eventually share with the world, bought his daughter a camera for her 12th birthday — it was a Brownie, the Eastman Kodak box camera that launched so many illustrious careers.

A year later, she made her first photographs while attending the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis. In 1908, at age 17, she graduated to Autochrome prints, an early color process. Then, in 1917, she moved to New York to study at the Clarence H. White School of Photography, which the acclaimed Mr. White opened in 1914 in a brownstone church on the east side of Greenwich Village.

She didn’t stay long, though. In 1918, Ms. Gilpin was downed by influenza. Her nurse, Betsy Forster, became her constant companion, and together they traveled west, landing first in Colorado Springs. According to the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, she returned home to establish “a publishing company and her own studio for portraiture and architectural work, but left to work for the Boeing Aircraft Corporation during World War II. After the war she settled in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where she supported herself with commercial assignments while working on her personal projects.”

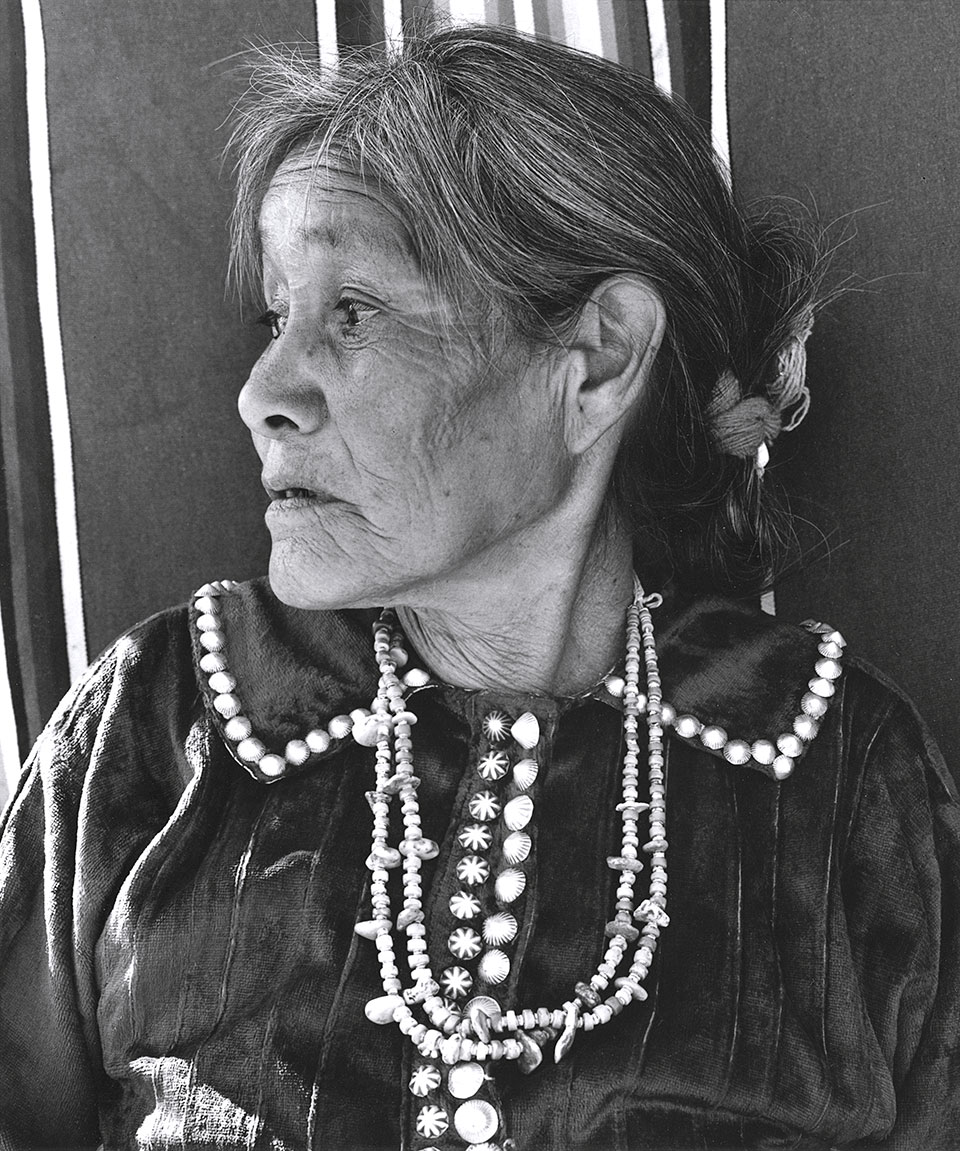

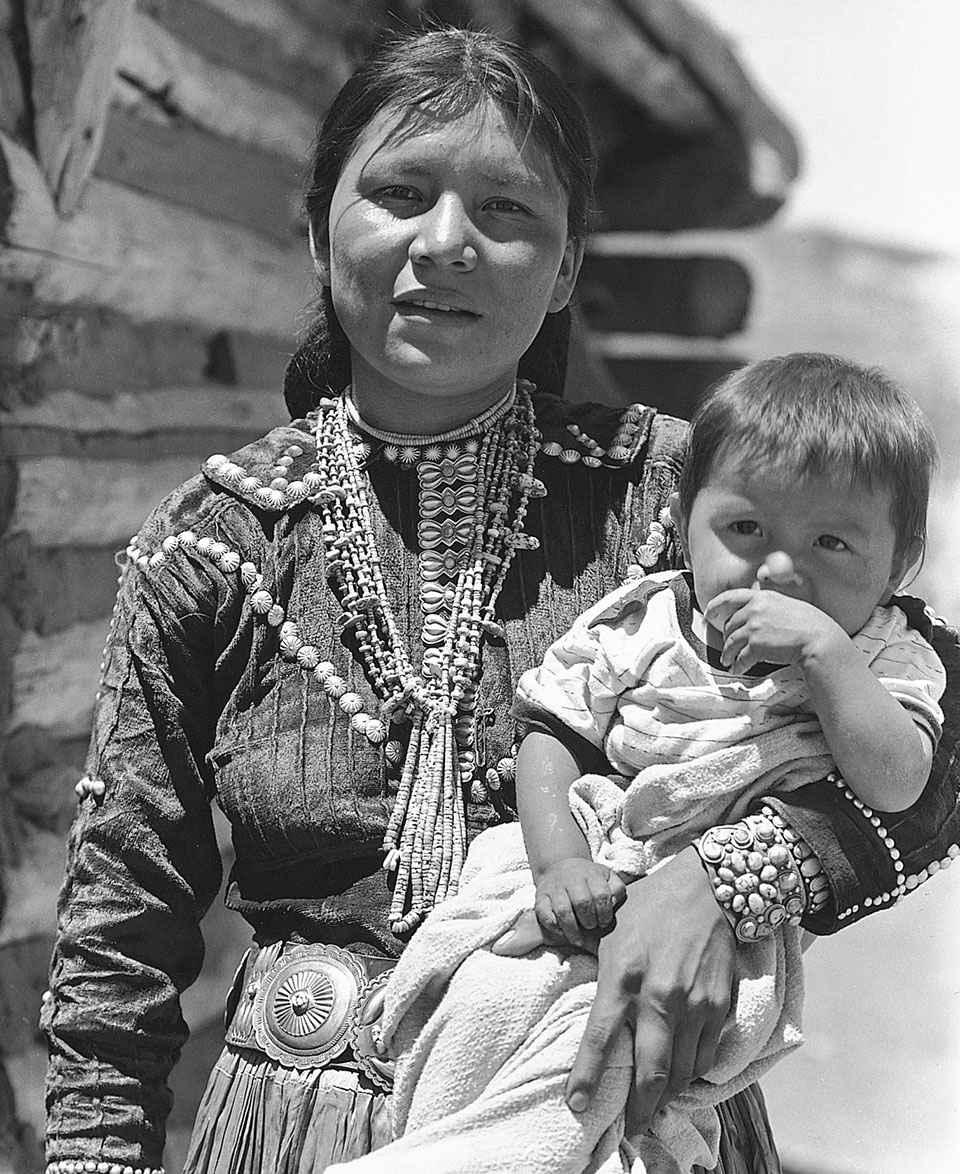

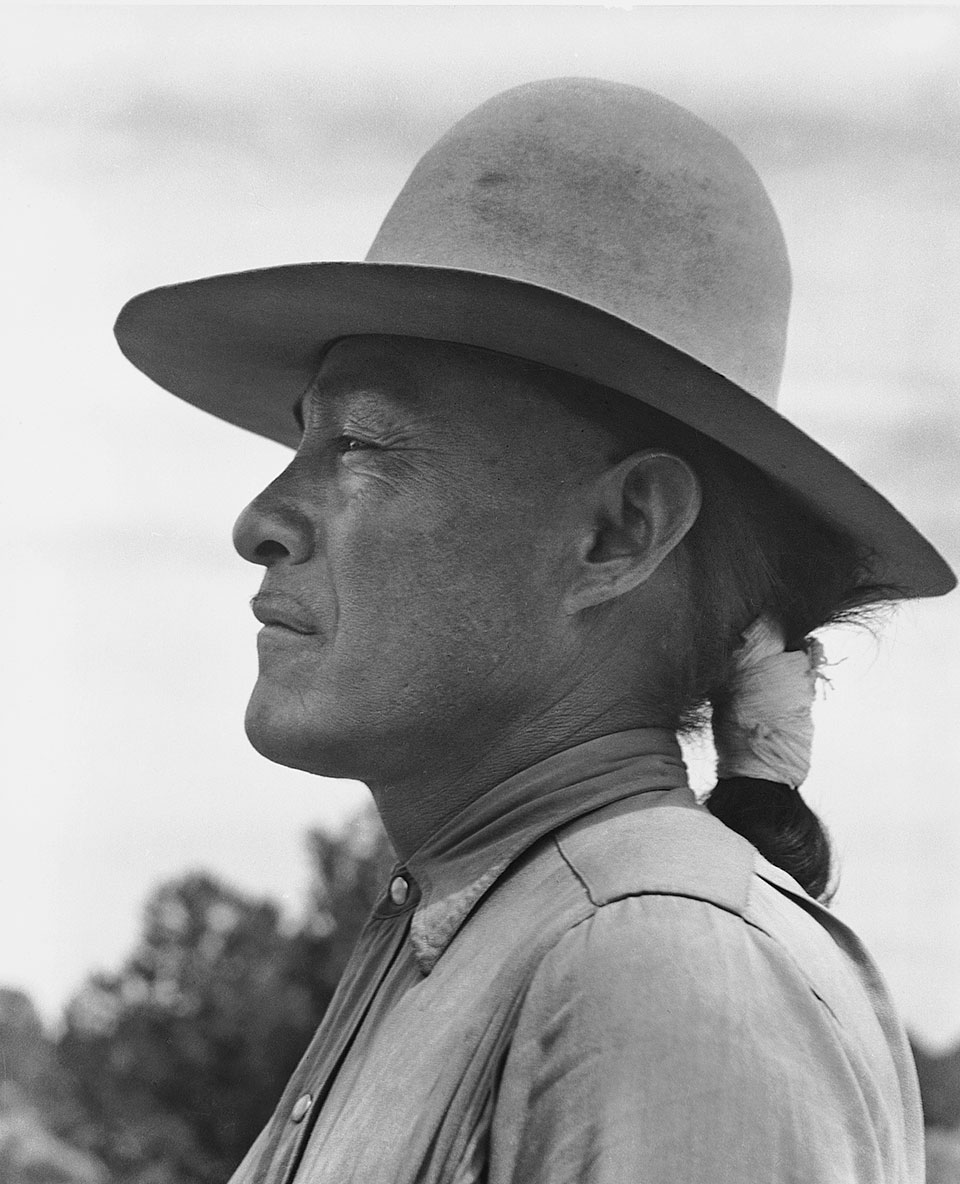

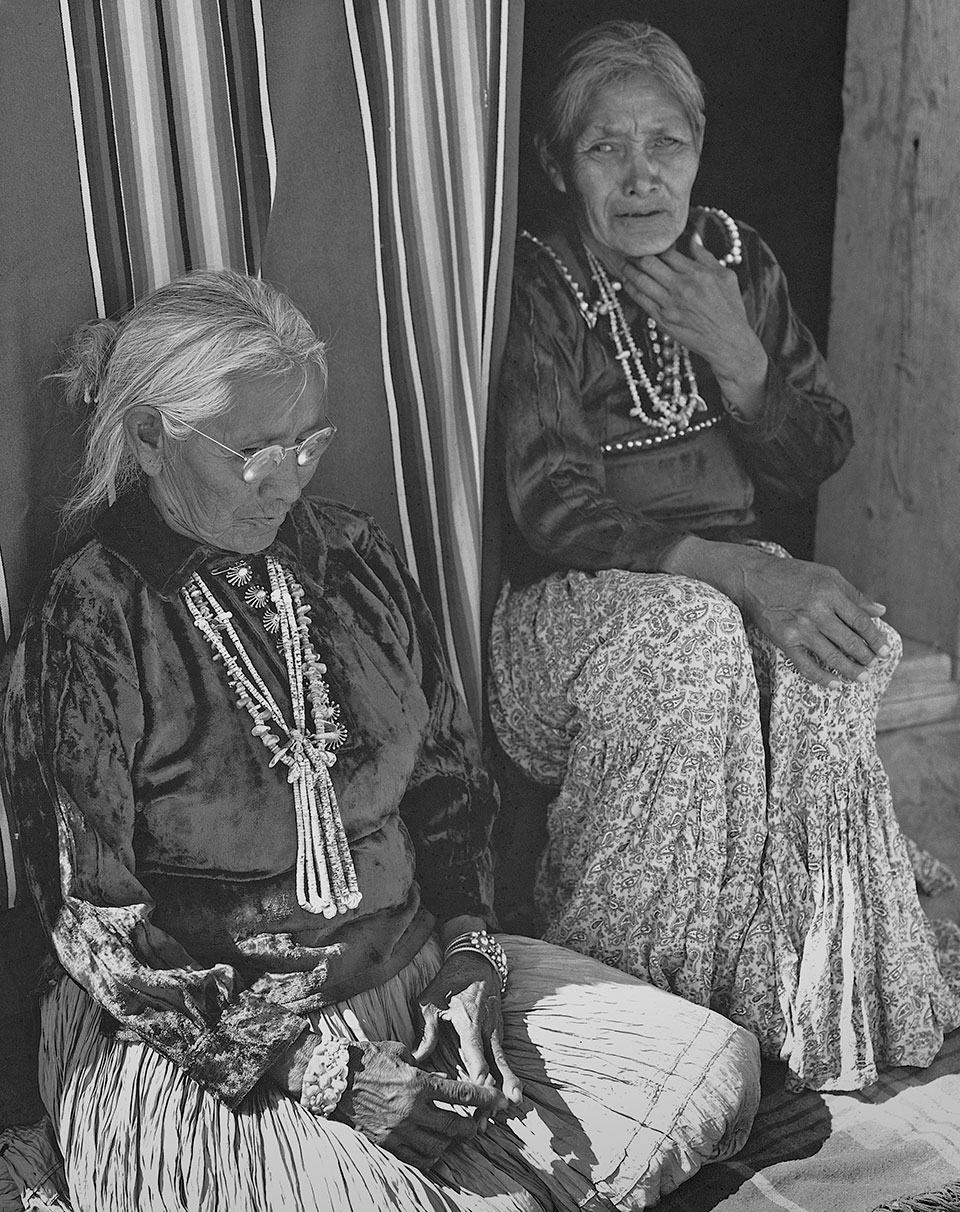

Among them were several books, including Temples in Yucatan (1948) and The Rio Grande (1949), both of which she wrote and photographed. Twenty years later, in 1968, she would publish what is arguably her most important book, The Enduring Navaho.

“Within the boundaries of their 25,000-square-mile reservation,” she writes in the book’s preface, “more than 100,000 Navaho People, the largest tribe of Indians in North America, are striving for existence on a land not productive enough to sustain their increasing population.”

Thus the word “enduring” in her title.

“Gilpin found no evidence that the tribe Edward Curtis once referred to as ‘the vanishing race’ would soon disappear,” Martha Sandweiss writes in her analysis of the book. “The Navajo she depicted could accommodate to change as easily as they could adapt to their desert environment. Most important, they could do so without losing the essential values of their culture.”

Toward the end of the book, Ms. Gilpin offers a note of hope, one that’s echoed today — more than 50 years later. “Many who know the Navaho will think that the great days of ceremonialism are lost,” she wrote. “Possibly this is true, but I cannot believe the old ways will really be lost. ... We can but hope that those essential qualities of the Dinéh will never be lost. Song and singing are the very essence of Navaho being, and as long as the Navaho keep singing, their tradition will endure.”

In 1972, at the age of 81, Ms. Gilpin made one final visit to the Navajo Nation — to create a book of images from Canyon de Chelly. While working on the project, Sandweiss writes, one of the Navajo families she photographed put on a picnic in her honor. It was a show of appreciation for the gift of a photograph she’d made of a deceased family member.

“It was a Navajo gift,” Ms. Gilpin said. “That was a day I’ll never forget, because it just summed it all up. ... It was just that I was accepted by them, I think, as much as anything else — as somebody that understood them.”

Sadly, the Canyon de Chelly project was never completed. Ms. Gilpin died in 1979. Upon her death, she left her photographic estate of 27,000 negatives and more than 20,000 prints to the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, Texas.

— Robert Stieve