Chiricahua National Monument is known for its rhyolite hoodoos, stone pillars carved by natural processes over thousands of years. But just northwest of the monument’s visitors center are two stone pillars of a different kind. They’re the only standing reminders of a long-gone destination — and, for Susan Reedy, an important chapter of her family’s history.

“My generation is the only generation that heard it from the people who were there,” she says. “It’s a part of the history of that area, and if I don’t say something, the next generation will be further removed from it.”

Indeed, most visitors to this corner of Southeastern Arizona have never heard of the Silver Spur Guest Ranch, and the only reference to it on the monument’s website is in relation to the Silver Spur Meadow Trail. That easy hiking route leads to the stone fireplaces that Bill Spragge, Reedy’s grandfather, commissioned while he developed the ranch in the 1940s. Now, Reedy is hoping more people learn about what she calls “kind of a forgotten place.”

Some of the Silver Spur site’s history is relatively well known. Its original owner, Ja Hu Stafford, moved to the Chiricahua Mountains’ Bonita Canyon with his wife, Pauline, in the late 1870s. “He homesteaded in the canyon, and this was part of his property,” says Suzanne Moody, an interpretive ranger who’s been at Chiricahua National Monument for almost three decades.

Later, Stafford sold the parcel to Lillian and Hildegard Erickson, the daughters from the family who developed Faraway Ranch a quarter-mile to the west. After Hildegard married and left the area, Lillian and her husband, Ed Riggs, rented the property to the federal government, and in 1934, it became a camp for the Civilian Conservation Corps, the Great Depression-era program that contributed infrastructure development to many National Park Service sites.

The CCC’s Company 828 lived and worked in Bonita Canyon for six years. “They did all the visitor and staff facility development” at the monument, Moody says, including improving the scenic drive through the canyon, building trails and a campground, and constructing staff housing and a fire lookout.

“Visitors have the Civilian Conservation Corps to thank for everything at the monument which has been done to promote their convenience and pleasure,” Park Service official Frank Pinkley told The Arizona Republic in 1936. The crew also built its own camp, the centerpiece of which was a large mess hall. But after the company was transferred to a Colorado project in 1940, the Riggses began renting the site out to church gatherings and other groups.

That was around the time Spragge entered the picture. Born in Rochester, New York, in 1895, he moved to Buffalo as a teenager and worked a variety of jobs there, including in the auto industry and as an importer. “He was a very creative individual,” Reedy says — in the 1920s, for example, he made a collection of miniature model airplanes from scratch. But Spragge developed health problems ill suited for the climate in Western New York, and in 1941, a doctor’s advice sent him on his first trip to Arizona. He initially visited Douglas, where the local chamber of commerce recommended Faraway Ranch. There, he struck up a friendship with Ed Riggs, and together, they explored the monument’s attractions and hiking trails.

“He fell in love with the place,” Reedy says. “He fell in love with the independent life and living out in this open area with so much natural beauty. He just had this idea that he wanted to start a guest ranch of his own. I think of that now — of him going back to Buffalo and telling his wife, ‘This is what I want to be doing now.’ ” She believes her grandfather’s natural

creativity helped him envision the CCC camp as a destination for travelers.

Over the next few years, Spragge spent plenty of time in Arizona, joined at various times by his wife, Jessie, and sons, Bill Jr. and Bud (Reedy’s father). “He didn’t have a typical adolescent experience,” Reedy says of her dad. “Eleven years old, average life in Buffalo, and all of a sudden, you’re on a horse.” Bud stayed in Arizona for longer stretches as he got older, taking correspondence courses so he could keep up with school.

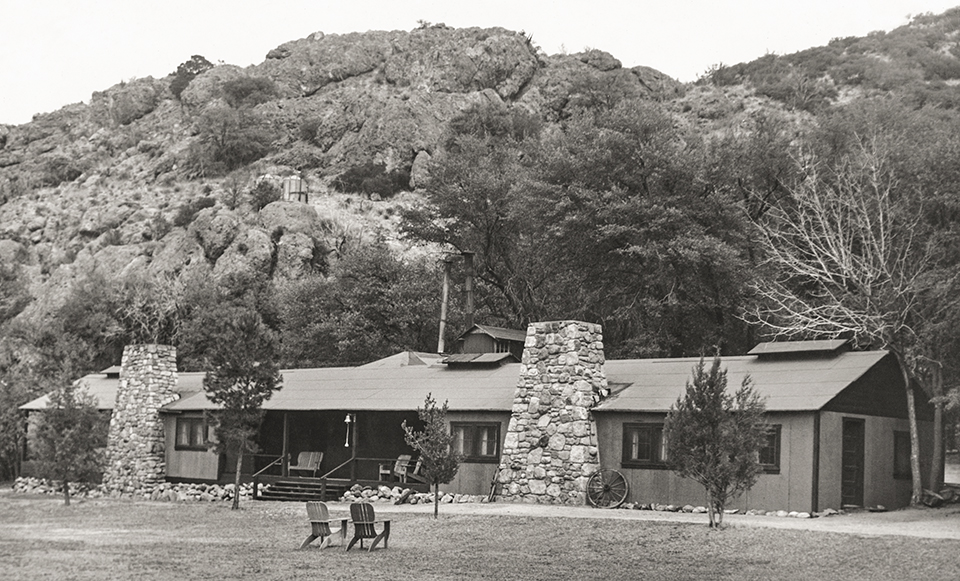

Spragge eventually cobbled together enough investors to buy the property from the Riggs family. He had big plans for the CCC buildings, and a watercolor and pencil sketch shows his early vision for the mess hall. He converted that structure into a lodge, which he renamed the Long House, and added two stone fireplaces he commissioned from Tucson mason Red Wright. He christened the property the Silver Spur Guest Ranch and designed the ranch’s brochure and letterhead himself, incorporating Bud’s drawing of his older brother’s boot spur.

World War II led to manpower and material delays, but the ranch was finally ready for guests in August 1945. And Spragge was clear about the type of guest he hoped to attract. Ahead of the opening, he told a newspaper that the starting daily rate, “including everything but saddle horse,” would be $5 — the equivalent of $83 today. “We’re not going to cater to the luxury trade,” he said. “The Silver Spur will be a spot where the average wage earner may come for an enjoyable and comfortable stay.”

Photos from the years that followed show the family fully invested in ranch life. In one, Spragge, Jessie, Bud, Bill Jr. and ranch hand Dick Spaulding pose in cowboy hats and Western dress shirts during one of the chuck wagon dinners for which the ranch became known. Spragge died when Reedy was very young, so most of what she knows of those days came from her father. She says he embraced the lifestyle change.

“It was such an extraordinary experience to be plucked from this life [in Buffalo] and land there, because he was at an age where it was not his choice to do so,” she says. “But he really thrived in that environment.” Bud helped with chores and running the ranch, but he also had plenty of freedom to explore his expansive surroundings, and there were tales of hiking up Cochise Head and of a captured pair of mountain lion cubs that were being trained for roles in a movie.

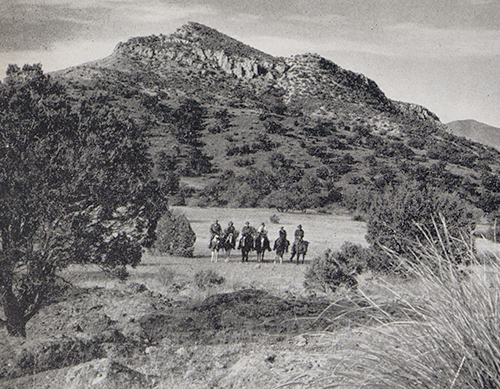

The Silver Spur was equally memorable for guests, who enjoyed hikes around the monument, trail rides on leased Faraway Ranch horses, and dances in the recreation hall. A Happiness Tours “Three Nations” trip — one that embarked in Chicago and took passengers by train to destinations in Mexico, Canada and the American West — stopped at the ranch for a chuck wagon dinner in 1946 and 1947. “The tourists were greeted with a rousing welcome that is typical of the Old West,” the Arizona Range News in Willcox reported in 1946. “Cowboys were on hand when the train arrived and added local color to the affair.”

Around 1948, the Spragges left the ranching business and returned to Buffalo — with the exception of Bill Jr., who went to California to raise his family. A split among the ranch’s investors had led to the Spragges being leveraged out. Ray and Ruth Kent, a St. Louis couple as unfamiliar with Arizona ranch life as the Spragges had been, took over in 1949 and ran the Silver Spur for nearly two decades, and newspaper accounts from that time indicate that the ranch became a popular honeymoon destination.

In 1968, the Park Service bought the property and added it to Chiricahua National Monument, and the buildings were later demolished, with only the stone fireplaces left standing. As a result, Moody says, the Silver Spur has become “a little-known and often-forgotten part of the monument.”

In some ways, that was true for Reedy, too. But when her father died in 2018, she inherited his collection of photos and other memorabilia, allowing her to get a fuller picture of the role her family had played. She later provided copies of those items to the Arizona Memory Project, an online repository of documents that chronicle the state’s history; they can be viewed in the Silver Spur Ranch collection. Reedy hopes having those items publicly available will lead to more people learning about the guest ranch her family founded in the 1940s — and visiting the site itself.

In the meantime, Reedy is still waiting for her first visit. She’s back in Buffalo, and for years, she and her brother have been hoping to make a trip to Arizona, but the COVID-19 pandemic and health issues have led to delays. When they finally come, they’ll be able to walk the Silver Spur Meadow Trail, which goes right through the footprint of the Long House. There, in an idyllic meadow dotted with alligator junipers, they’ll find those two fireplaces — relics of the years when their family took a break from East Coast life and served chuck wagon dinners beneath the hoodoos of the Chiricahuas.

To view the Silver Spur Ranch collection at the Arizona Memory Project, visit azmemory.azlibrary.gov/nodes/view/207.