State parks often protect cultural, historical and natural resources and provide education and recreation. But one of Arizona’s newest state parks — which honors the 19 Granite Mountain Hotshots who perished in the Yarnell Hill Fire — also serves a higher purpose.

“I have a very unique park,” says ranger Jared Welsh, who lives in the neighborhood that was hit hardest by the 2013 fire. “You meet some amazing people at this park because of its significance. And that’s definitely different than other parks. People come here with love in their heart.”

“Love” is a word nearly everyone involved with the park uses when talking about it, because to most of them, it’s personal. For those who knew the hotshots or their families, building the park was a labor of love. And for those who didn’t, it quickly became one.

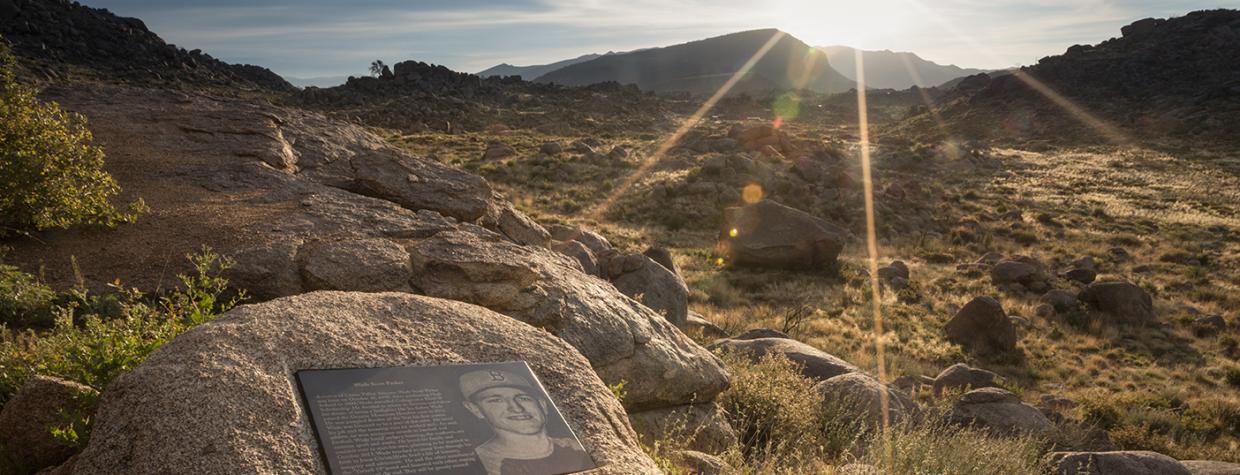

Located southwest of Yarnell, Granite Mountain Hotshots Memorial State Park includes a strenuous, 2.9-mile trail that climbs 1,200 feet into the Weaver Mountains, to a spot overlooking the place where the 19 hotshots deployed their shelters for the last time. It’s a physical, educational and emotional journey that includes interpretation of wildland firefighting and fire ecology, along with plaques with the hotshots’ pictures and stories. A shorter, steeper trail leads down to the deployment site, where 19 metal crosses mark where each hotshot was discovered.

More than 120,000 people have visited the park since its dedication in 2016. Some come because it’s a beautiful trail with sweeping views in all directions. But many, including firefighters from as far away as Australia and Iran, come to pay their respects. It’s also a place where wildland firefighters come to try to understand what happened on June 30, 2013, so it doesn’t happen again.

“On Sunday evening, June 30, [Arizona House] Speaker Andy Tobin, who was my seatmate, called me and said, ‘Karen, we’ve had something really awful happen,’ ” recalls Karen Fann, now the Arizona Senate president. “Some [of the hotshots] were personal friends of ours, as were their families. Wade Parker’s mom and dad worked for me in my construction business when Michelle was pregnant with Wade. So, I’d literally known him from the day he was born.”

Fann, who lives in Prescott, attended meetings organized for the hotshots’ families at Prescott Mile High Middle School. “The first day … there was just a small handful of people there, people who were close by,” Fann recalls. “Every day, that group just got bigger and bigger. … There were more and more people you knew, and you didn’t realize how everybody was so related and connected. It was heartbreaking. It really was.”

Knowing the deployment site was on state trust land that would one day be sold to support education, Fann began talking to Tobin about buying it. “I only wanted, originally, like 10 or 20 acres,” Fann says. “Then we started talking with the [Arizona] State Parks director and the state land director. … They said, ‘Yeah, we can do it, but we’re going to do a quarter of a section, because we don’t sell just 10 or 20 acres.’ ” And it had to go to a public sale.

Governor Jan Brewer threw her support behind the idea, and Fann sponsored the legislation that allowed the state to buy the land and establish a board to oversee the design and development of a state park. The board would include State Parks employees, state and local officials, citizens, fire chiefs, family members and the lone surviving member of the Granite Mountain Hotshots.

The sale of 320 acres, a half-section, took place at Prescott’s courthouse with many of the hotshots’ family members present. There were no other bidders.

With so much land, the project immediately got bigger. “We looked at all kinds of ways to get to the site,” recalls Chuck Tidey, who represented the Yarnell-Peeples Valley Chamber of Commerce during the process. “The one thing we didn’t want it to be was a drive-by.”

Ken Sliwa, State Parks’ community relations administrator, recalls that some board members originally didn’t want anyone to visit the deployment site, thinking it should be hallowed ground. “As that conversation kept going,” he says, “they decided that to be able to hike into the site would give a bit more of the experience of what the hotshots did in support of the communities.”

For the families, the most important thing was to protect the deployment site. Eric Marsh’s widow, Amanda, took her role of representing the families’ wishes seriously. “It wasn’t easy,” she says. “There were so many people who wanted a voice into that state park. And for me, the only people who mattered were the families.”

Surrounding the site with 19 gabion boxes connected by a chain accomplished that goal and came to symbolize the bond that connected the hotshots. “I think everyone came together on it toward the end,” Sliwa says.

Trail construction wasn’t easy. The Weaver Mountains are rugged, and trail crews moved thousands of boulders, says Mark Loseth with Flagstaff-based American Conservation Experience, which built the trail. “It’s still the most challenging project that I’ve ever been a part of,” he says.

In the beginning, volunteer crew members camped nearby. But as they progressed up the trail, they camped along the ridge, with helicopters dropping off water. Each night, they took turns reading a chapter from On the Burning Edge, Kyle Dickman’s account of the fire.

“Once the plaques were installed, the meaning of the trail hit home for everybody,” Loseth recalls. “It was really powerful.”

Over the years, Sliwa has hiked the trail many times. “I’ve seen 95-year-old people, and classrooms of children with their teachers, and people who have traveled from all over the world to … give their thanks, and people who go up there every week and challenge themselves,” he says.

A few stand out. Like the class from Texas that saved up money for a year, and firefighters from Germany who made the trip with the sole intention of paying their respects. Firefighters from around the world have left patches, hats and T-shirts. A hotshot who knew Travis Carter and Jesse Steed returns each year and leaves a Pulaski, a firefighting hand tool, on one of the gabion baskets. Others bring painted rocks, wood carvings, murals and metal art.

“To me, that’s just amazing,” Welsh says. “That people are inspired to … make something, bring it here, hike it here, leave it here, just leave a piece of them behind.” He’s heard visitors recount spiritual and even supernatural experiences at the park, and he often checks the visitor log for last names that coincide with those of the hotshots. “I’ve met a lot of distant family members who come here to pay their respects,” he says.

And then there are the hotshot crews. “They’ll be fighting a fire in the area and … come here and hike the trail with soot still on their clothes,” Welsh says.

The park has also become an important training ground. Crews come for “staff rides,” parking where the hotshots’ buggies were found and following their footsteps, role-playing the events of the day. “They bring in subject matter experts … to lay down the groundwork,” says Welsh, who attended one such event. “ ‘We’re here where the Granite Mountain Hotshots had lunch that day, did this, this and this. What would you do with your crew?’ They really hammer out some decision-making skills.”

And then there was Jose “Firefighter Joe” Zambrano, with the El Segundo, California, Fire Department. Since 2013, Zambrano has run more than 80 marathons in full turnout gear to raise money for charitable causes. He graduated from the academy that hotshot Kevin Woyjeck attended and was working there as a mentor when Woyjeck was there.

After the fire, Zambrano reached out to Woyjeck’s parents, Joe and Anna, to say he’d like to do the same for the nonprofit they’d founded, the Kevin Woyjeck Explorers for Life Association. After running two marathons to benefit the organization, he told them he’d like to kick it up a notch. Zambrano’s idea was to run or walk from the Los Angeles County Fire Museum, where a Granite Mountain Hotshots buggy is located, to the park — a journey of nearly 400 miles — and arrive on the fifth anniversary of the fire.

So, on June 23, 2018, he set out, carrying the grommets left from a flag Woyjeck carried during the fire. He crossed the Mojave Desert in full gear, and on the day he walked into Parker at 6 p.m., the temperature was over 110 degrees. Every night, he packed his swollen feet in ice.

“It was emotional,” Zambrano says. “It was times when I don’t know I’m going to make it. But then it would be like, I’m getting to this mile. I’m getting to this little city. And then as soon as I get into the little city, there were people welcoming me and the fire department was welcoming. So, it was [like], OK, I’m not giving up.”

He arrived on June 30 and hiked the trail with a crowd of supporters, carrying flags to drape on each of the 19 gabion baskets.

“[The park has] impacted a lot of lives around the world,” Sliwa says. “I’ve heard that a lot from people who have donated their time or work or equipment, just wanting to be involved.

I think it becomes a lot more. It becomes a part of your life.”

For more information about Granite Mountain Hotshots Memorial State Park, visit azstateparks.com/hotshots.