Sharlot Hall - Historian on Horseback

My name is Sharlot Hall. I've climbed the mountains and they are my home. I am no man's woman. My heart and soul belong to this vast land of desert, cactus, pine, and mountain. I explored the heights and depths of the Grand Canyon and the vast terrain that lies to the north, riding horseback for days over hills and through washes. This is my home. A land of peace and beauty, of storm and unrest, of color and vibrance, of good times and hard. I lie here even now. Not in death, really, but on an eternal prospecting trip.harlot Hall first Two years later, she wrote of that trip: “In mid-February of 1882, I rode into Prescott on a long-legged dapple-gray mare who had just left her hoof-prints on the full length of the Santa Fe Trail. We had been three months coming like Abraham and his family seeking new grazing grounds.” Hardly could Sharlot have known what this place called Arizona Terri-tory held in store for her.

The Halls settled on Lynx Creek, southeast of Prescott, at a place theycalled Orchard Ranch. During her teen years, Sharlot toiled long hours at the ranch, helping her crippled father brand cattle, milk cows, split wood, pick fruit, and plant crops. She attended grade school, making the four-mile trip twice daily.

For one year, Sharlot lived in Prescott with the Adams family, to attend high school. But lack of funds at the family ranch and the failing health of her parents brought her back.

Once Sharlot found she could escape the bitter pains of reality by putting her thoughts and observations into words, she wrote continually, bits and pieces, on anything, about the Arizona land she wanted to explore.

So began a life-long interest in Arizona's Indians, its prehistoric peoples, its frontiersmen, and early pioneers.

She traveled into Prescott, then the territorial capital, often meeting the people who were helping shape and mold the embryo of a new state.

Her professional writing career was launched by Charles Lummis, a California editor who published her short piece on the history of camels in Arizona. It was the first of many stories and, later, poems. So impressed was Lummis with the young lady, he asked her to join his writing staff. “A genuine young frontierswoman,” he called her. “Not of the cheap drama and Sunday-edition counterfeits, but a fine, quiet, loveable woman made strong and wise and sweet by life in the unbuilded spaces.” As Sharlot's career blossomed, so did her relationship with the editor. She assumed more editorial duties, but she was not pinned down to particular assignments. She traveled often between Los Angeles and Arizona, keeping in touch with the Orchard Ranch and raising eyebrows that are still arched today over her love life.

In 10 years' time, Sharlot had contributed numerous pieces to Lummis' magazine, mostly inspired by the land, people, times, and intrigues of Arizona. But in 1906, Sharlot penned her most popular piece, simply titled “Arizona.” In that year, the “Wise Men of the East' were contemplating admitting the territories of Arizona and New Mexico as one state. That proposal made Ari-zonans hopping mad. President Roose-velt endorsed the plan and won Shar-lot's wrath. She hurried back to the ranch house and quickly penned a scornful, sarcastic piece designed to shame the all-knowing lawmakers, who would “sit at ease and begrudge us our fair won star.” Together with that scorching piece Sharlot wrote a 68-page study of Arizona's economy.

In December, 1905, President Roose-velt advised that Arizona and New Mexico be admitted into the Union as one state, a measure bitterly opposed. In response to her government in Washington, Sharlot Hall penned the following poem. In this first of eight stanzas, she painted a vivid picture of

Arizona that has remained unsurpassed over the years.

Arizona No beggar she in the mighty hall where her bay-crowned sisters wait; No empty-handed pleader for the right of a free-born state; No child, with a child's insistence, demanding a gilded toy; But a fair-browed, queenly woman, strong to create or destroy. Wise for the need of the sons she has bred in the school where weaklings fail; Where cunning is less than manhood, and deeds, not words avail; With the high, unswerving purpose that measures and overcomes; And the faith in the Farthest Vision that builded her hard-won homes. - Sharlot Hall from Cactus and PineWhether her work had any impact on Congress is not known, but in 1906 U.S. lawmakers amended the joint statehood bill, permitting the two territories to vote separately on the question. Arizona resoundingly rejected the proposal.

Then in 1909, Sharlot was appointed Territorial Historian of Arizona, the first woman to serve in a state office, even before women were permitted to vote. It was to be her most memorable challenge.

On October 1 of that year, Sharlot agreed to “faithfully and diligently collect data of the events which mark the progress of Arizona, from its earliest days to the present time, to the end that an accurate record may be preserved of these thrilling and heroic occurrences.” To Sharlot that was no job - it was the first love of her life. Besides, there was a salary. She received $2,400 per year and $1,800 traveling expenses. Good wages in those days, especially for a woman.

So Sharlot left the ranch and entered the State Capitol at Phoenix, blowing dust off old books and getting acquainted with antique documents held in private hands and public institutions. But that was only part of her plan.

What she really wanted to do was record the reminiscences of those who had a hand in the territory's beginning. They know the stories, they should tell them, she reasoned.

Setting out across Arizona, Sharlot became personally familiar with the places and people that would help her write intelligently of the area. She visited nearly every city and every town and mining camp in Arizona, reaching remote areas on horseback and making long trips by wagon and team.

After a year in the field, her thirst for knowledge was still unquenched. At the beginning of the second year, she started on one of the longest, most dan-gerous, but rewarding journeys of her life.

On July 23, 1911, at age 40, Sharlot and guide Allen Boyle of Flagstaff, a stout traveling wagon, and team of horses started off for the Arizona Strip, From the ferry they went on to House Rock Valley and across the Kaibab Plateau, spending glorious days on the North Rim of the Grand Canyon. And Sharlot wrote about it in detail.

Heading westward, they struck Kanab, Pipe Spring, Hurricane, Zion Canyon, and the Mormon villages along the Virgin River. Next, they edged their way to St. George and then on to the Grand Gulch mines. From there it was into Nevada, then south, hitting mining districts in the Cerbat Mountains of Arizona. Finally, 75 weary days later, the pair reached Kingman. “From a hilltop we saw the dark smoke of a puffing railroad engine, and I did indeed say some prayers of gladness - for a thousand miles in a camp wagon is no joke, even when every day is filled with interest and the quest of fresh historical game,” the historian wrote.

Sharlot had fulfilled a dream. She saw an unknown and she went to explore. Her reports of the area flowed into Arizona, the New State Magazine, for 18 months, until statehood was achieved in 1912.

After that, Sharlot resigned her job as historian to return to her aging parents at Orchard Ranch. There she remained to run the operation until 1922.

That year a small group of Prescott business and professional men, calling themselves the Smoki, were developing an annual pageant based on Indian themes. They asked their neighbor and friend Sharlot to write a pamphlet describing their purposes. “The Story of the Smoki People” rekindled the age-ing woman's interest in writing. She brought out a second edition of a book of poetry, Cactus and Pine, having written the first before her mother's death in 1911.

She was one of Arizona's Republican electors in the national election of 1924, and was chosen to hand-carry Arizona's vote to Washington, where she stayed to witness the inauguration of Calvin Coolidge. To the ball, she wore a turquoise gown with shawl and purse woven from copper fibers, another plug for her adopted state.

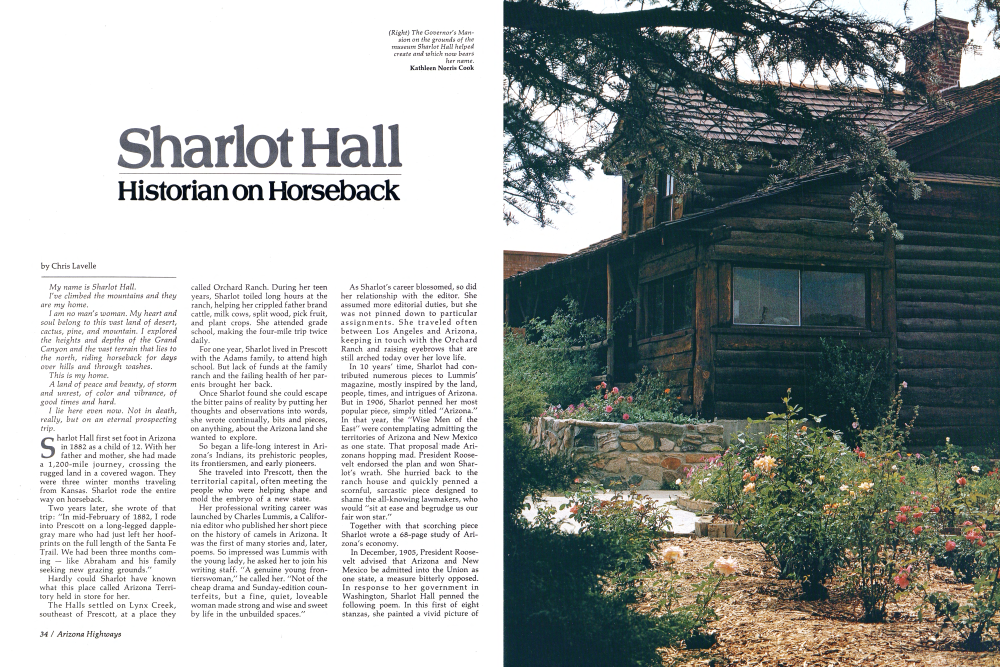

In 1928, her father's death set Sharlot free. She moved to Prescott to take up permanent residence at the old Governor's Mansion. She leased the sorelyforgotten historical building, moved in with her extensive collections of artifacts and relics, and continued gathering bits and pieces of Arizona history.

The last 15 years of her life were spent restoring the old log mansion to its original beauty.

Sharlot once wrote about the house.

To her, it was an alive place, filled with alive persons and animate objects. Its history is a living one, and that thought continues today.

Sharlot Hall died on April 9, 1943, at the age of 73, her vast collection of artifacts and the Governor's Mansion forming a cornerstone of today's Sharlot Hall Museum in Prescott, a living monument to the places and things Sharlot Hall loved best.

In 1973, Dr. Kenneth Kinsey, Ph.D., stepped into the directorship of the museum. His mission: to preserve and bring to life this state we call Arizona. On the grounds of the museum today, in addition to the Governor's Mansion, stands old Fort Misery, a one-room schoolhouse, and the charming Frémont House, home of John C. Frémont, western explorer and fifth territorial governor of Arizona.

The Frémont House was donated by the Methodist Church of Prescott, and land to the east of it, acquired in 1972, sealed the state's commitment to expand the historic site.

The Bashford House, a splendid example of life in the 1880s, was moved to museum lands in 1973, following a threat to tear it down. People raised such an uproar that the house finally was offered to the museum if they would have it moved.

The estimated cost of the project was a staggering $25,000, to be acquired within three months. Every organization in town without exception pooled their efforts, and in a unified push, the house was moved to the museum site within the three-month deadline. Today, the building is still undergoing restoration, most of the money being raised locally.

When space for new exhibits finally ran out in 1974, Prescott sought and received a federal grant to design a new museum building. The $1.4 million facility opened in March, 1979, the pride of Prescott. Heated by solar energy, the building includes a large community room for meetings, demonstrations, and learning experiences, sponsored by the museum. A cozy living room atmosphere has been created in the reading room with a fireplace and overstuffed chairs. And a library and archives allow for organized arrangement of the museum's many documents.

History is a people's collective memory; the museum is a tangible part of that history, philosophizes Dr. Kinsey. To be interesting, educational, exciting, the museum must be very alive and that's the only real guidebook Kinsey uses.

People are discovering museums, Dr. Kinsey says. Arizonans are looking, too, searching for roots, meaning, even direction in today's mishmash society. Sharlot believed the past tied directly to the present and into the future. No time stands alone, and to lose one part of it is to create a void that cannot be replaced. Avoiding those gaps is the aim of the Sharlot Hall Museum.

The new building has relieved pressure of the passage of time. Exhibits stuffed in attics and corners of storerooms across town now see the light of day and are there for others to see. Every day interested residents, both longtime and those new in the area, bring items to the museum. It's a community spirit that turns up new twists of history on a regular basis. "Every time a group visits, we get a new sense of history," says archivist Sue Chamberlain.

Sharlot, who felt western pioneers were the best people in the world and wanted that to be remembered, would be pleased to read the roster of visitors, more than 50,000, who come here each year from all over the world to see the museum's collection. In addition to Southwestern Indian artifacts, mining tools, and artifacts, in the fall a Folk Arts Fair features costumed demonstrations of the nearly lost arts of weaving, spinning, butter-churning, quilting, woodworking, and blacksmithing. They also see one of the first metal windmills manufactured in the United States the only one remaining in this country a pioneer herb garden, and a rose garden, fragrant and colorful, with each of the 350 roses honoring an outstanding Arizona woman.

But the Sharlot Hall Museum is something more than a place where things of the past are put on display. In Sharlot's own words: These rough walls the memories hold Of the long-past days of gold; A shrine beside the busy way To hold the Soul of Yesterday.

Already a member? Login ».