Smoke from a controlled burn on Observatory Mesa drifts across Flagstaff, and the faint whiff of burning wood works its way through the tall, narrow windows of Navajo artist Shonto Begay’s second-floor walk-up studio.

“It’s a good place,” Begay says of the high-ceilinged space in a 19th century brick building on downtown’s Aspen Avenue. Forests of brushes, from wall brushes to fine rounds for detail work, poke out from a half-dozen paint-spattered cans crowding his worktable.

On a quiet Saturday morning, Begay settles into a squeaky, old-fashioned desk chair in front of an easel and turns his attention to a large horizontal painting depicting boys at an Indian boarding school. They’re wearing matching uniforms of dark pants and white shirts, and Begay mixes acrylic paints on a wooden palette, then dabs the boys’ featureless faces to refine the skin tones.

Watching Begay paint, there’s a sense he’s engaged in ritual. The Neo-Impressionist describes his brushstrokes as “a visual chant,” in which lines of different lengths, widths and shapes — swirls, curls and dots — are akin to syllables that add up to words, then to sentences and paragraphs, and finally to Navajo prayers. He puts more strokes to the canvas, chanting with each one, to emphasize his point.

2021, acrylic on canvas, 20 by 24 inches

“That’s how it began: in a huddle with the medicine men, creating a healing mandala sand painting way back as a kid,” Begay says. “So, I’ve always seen my work as a ceremony. More than trying to achieve something with shock value or mimicking a photo. Mimicking realism. Or being just too mysterious. I celebrate the visions I see, the things I know, through these prayers. Broken into syllables, into lines. That’s what I’m conscious of. That’s the only part I’m conscious of. Everything else, I’m pretty much just following the road map of the heart.”

He depicts sacred visions and mystical landscapes, but also hitchhikers in the beds of pickup trucks, windmills and wind-wrecked trailers, twisting junipers, and coyotes running across two-lane roads that disappear beyond distant mesas and into the infinite. He can be darn funny, too, even portraying himself squeezed into a pickup’s front seat between Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings as a glowering state trooper approaches the trio during a traffic stop on U.S. Route 160.

In Diné, shonto means “sunlight on water,” and Begay’s works have a luminous, liquid ephemerality that conjures the spiritual realm just beneath the surface of the material world. His swirling, colorful skies bear a cursory resemblance to those of Vincent van Gogh, but Begay instead sees parallels to the paintings of Australia’s Indigenous peoples. He incorporates pop culture into his work, too, and credits Norman Rockwell, Thomas Hart Benton and Winslow Homer as major influences.

Begay finds beauty in the idea that each stage of life is like a lifetime unto itself — maybe because his own 67 years have been so picaresque, with stints as a national park ranger, a wildland firefighter, a newspaper columnist and part of the support team for a professional boxer. He’s also an educator and has written and illustrated children’s books focused on American Indian themes. Through it all, Begay has told stories to keep both himself and Navajo traditions alive.

“Life presents us with so many wonderful plays, little dramas,” he says. “Every breath you take is a great story.”

Begay grew up the fifth of 16 children in the Kletha Valley, near Shonto, on the Navajo Nation. His mother was a rug weaver, his father a medicine man. The family lived in a hogan with no electricity or running water, and Begay immersed himself in the stories and songs of his elders, watching as his mother and aunt worked on their weavings every day.

“Pretty much all of my maternal family were weavers,” he says. “That’s pretty much what they did. And people in my family were also very, very holy people. Shamans, medicine people, and also drunkards. Those two very diverse qualities, they competed. Demons and angels.”

As Begay rambled across the vastness while tending sheep, his imagination roamed free. “Being a shepherd, I was spending many hours, many days, alone with the sheep and a sheepdog and a donkey,” he recalls. “Way out there on the hills and in the valleys. The canyons. Being surrounded by this glorious scene. It was fantastic. The trees, how they were shaped. The bushes. Everything demanded some kind of attention.”

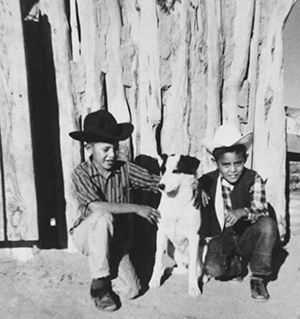

But Begay says Navajo children grew up knowing that one day, everything would change — that they would be taken from home and sent to a Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding school. Begay was just 5 or 6 when a government agent kidnapped him on a sheep trail.

“I was bewildered more than I was sad or more than I was angry or anything like that,” he says. “More bewildered. Until then, I thought my whole world was just my horizon, where I herded the sheep. Black Mesa to the east, Long Mesa to the west, Navajo Mountain on the far north, and Tonalea and the [San Francisco] Peaks way down to the south. That was my world. Beyond it, nothing existed. Then, all of a sudden …”

Begay describes himself as “an inmate” at the school. His mother and father lived only 10 miles away, but during the school year, he wasn’t allowed to see them. Administrators changed his name to Wilson. The school ordered the boys to dress the same, he says, and their hair was immediately shorn. They were forbidden to speak Diné and recited from a sign that read, “Tradition is the enemy of progress.” The children underwent religious indoctrination and watched black-and-white B-Westerns intended to instill shame about their culture. “The cavalry came over the hill, and the savages were driven away,” he recalls of those films. “Psychological abuse — that’s pretty much what it was. Spiritual and psychological abuse.”

When summer arrived, he could finally return home. “We were released,” he says. “It was a joyous day. What a joyous day. My God, that was a joyous day.” He revels in the sense of liberation, even decades later. “You survived,” he says. “You could kick your shoes off again and run with the goats all summer long. Be part of ceremonies. Speak Diné. Hear stories. All of that again. Until fall.”

The land told him when it was time. “In the summer, the sunflowers are happy and their heads are high,” he says. “Then the heads start dropping. That’s how I knew the day was coming.”

There was no resisting. Parents who tried to keep their children at home were thrown in jail, and Begay’s mother and father served time. Government agents came around picking up kids, and he remembers cars approaching in the darkness. “You had to sleep with one eye open,” he says. “You were woken up out of your hogan, out of your sheepskin. You’d run up the hill, way into the hills on the side of the mesa, and you’d camp out there the rest of the night, and they’d be looking around with their flashlights at the sheep camp. That’s how it was.”

Art became Begay’s refuge. He escaped into imagination and dreams, creating a universe of his own where he could feel safe — and maybe even be a hero. He found artistic inspiration in unlikely places, from depictions of Jesus herding sheep in the proselytizing pamphlets of missionaries to classic cartoons and comic book characters: Sad Sack, Huckleberry Hound, Superman, Sergeant Rock and the Green Lantern. Begay loved Eerie and Creepy, two oversized horror comic magazines that he says masterfully depicted the human form and action while always advancing the story.

2019, acrylic on canvas, 50 by 82 inches

But nothing could quell his longing for freedom. On one especially bad day, Begay says, a student named Floyd, who aspired to be a medicine man, announced, “We are going to go home this afternoon. We’re going to pray to the spirit of the great wind. And the great wind will descend upon us and we will be transported back to our homeland.”

A group of boys walked to a mound behind the dormitory. They closed their eyes as Floyd led them in song and prayer. Begay then looked out and saw a giant dust devil form over the desert: “It swirled and danced, and I thought, Here it comes; we’re going to go home!”

He shut his eyes again, then took another peek, only to see a bigger dust devil coming up the hill, right at the boys. The whirlwind dropped below a ridge before twisting behind the water tower, scattering tumbleweeds and trash.

“I said, ‘We’re going home; hang on!’ ” Begay says. “I closed my eyes, even more tightly, and slowly opened them. But we were still standing there. I was so sad, so disappointed.“Then Floyd said, ‘It didn’t work, because someone had his eyes open.’ ”

One summer when Begay was a teenager, he went back to the family’s sheep camp to help with chores, then realized his siblings could take care of the work. “I was outta there,” he says. “Changed my clothes, put more clothes in a duffel and $5 in my pocket, and hit the road. Every summer after that, I just hitchhiked, never really having a destination.”

Begay picked up rides in whatever vehicle stopped — family station wagons, motor homes, converted school buses. Sometimes he headed home to check on his family, then, after attending a ceremony or gathering, returned to the road. “I was young; I was mesmerized,” he says. “Nobody asked you where you were going. Or where you’re coming from. You just are.” The rides, he says, offered stories the same way his sheep camp had.

He attended three high schools, finishing in Santa Fe because he was deemed “too incorrigible and distracting” to stay on tribal land. He later enrolled at Santa Fe’s Institute of American Indian Arts, where, for the first time, he met students from other tribes. “That opened my world quite a bit,” he says. “It was really inspiring because of what other people were creating and representing about their tribes. I was seeing some really fantastic art and thought, I can do that. But for months, I didn’t. I was kind of ‘shelled up’ and just watched others do. Finally, I tried my hand at it.”

His art took him to new places. From New Mexico, Begay went to the Bay Area to attend the California College of the Arts, where he completed 10 ballpoint drawings of the Navajo Hero Twins legend that now are part of the permanent collection at Santa Fe’s Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian (which recently featured a major exhibition of 40 Begay works).

He has painted professionally since 1983, never letting go of a powerful belief: Art saves lives. Begay’s success — indeed, his very survival — stands in marked contrast to the fate of his close group of friends from childhood. Ten of those 13 boys are dead, done in by violence or alcohol. “When you’re raised in an institution that devalues your culture, the very core of your being and your existence — your stories — then everything else kind of shatters in your life,” he says. “A lot of the kids didn’t have the outlet that I had.”

Begay puts aside the Indian school painting and turns his attention to another canvas, where a coyote stands in front of a petroglyph panel with cliff dwellings tucked into an alcove behind it. He takes a small brush and with quick, short strokes adds white highlights and texture to the coyote’s muzzle and legs. He talks about his many school visits and how he tries to inspire and give kids hope through art — and by sharing the story “of how I got from there to here.”

He adds, “I still go back to where my umbilical cord is buried: on the Shonto, where my house is built. It’s a place that ties you to the Earth, ties you to life, ties you to the universe. To know where you sprang from, where the Earth hugs you for all time. That’s why they say you can go anywhere in the world and feel at home.”