On a cloudless August morning, the Hassayampa River Preserve’s namesake waterway runs crystal clear along its sandy course while summer tanagers, warblers and indigo buntings chatter in the lush cottonwood canopy overhead. This spot near Wickenburg is one of the few places the river reliably runs above ground, unspooling southward like a lifeline for desert animals and as many as 300 documented species of birds.

Today, the river hardly seems worthy of its designation. Narrow and slow-moving, it looks more like a gentle stream. Yet branches and trunks littering the ground offer evidence of the river’s volatile nature. So does the yellow caution tape that stretches across two sections of trail where, just the week before, members of the preserve’s staff arrived to find two small footbridges washed away.

It was hardly the first time the river had risen, as rivers do. But the Hassayampa’s most tragic flood was not a natural occurrence but a human-made disaster. On February 22, 1890, a dam at Walnut Grove collapsed, sending 4 billion gallons of water downstream. The resulting flood destroyed everything in its path and killed as many as 100 people.

The dam’s failure is considered one of the biggest disasters in Arizona history. But it may have saved the river.

In 1863, prospectors discovered gold along the upper Hassayampa and two of its tributaries. The gold seekers who followed included a New York lawyer named Wells Bates and his brother DeWitt. In 1881, while operating a small mine west of Rich Hill, near present-day Congress, the Bates brothers became interested in mining along the Hassayampa in the nearby Weaver Mountains.

They purchased property near Walnut Grove and, filing a claim for all of the river’s water, created the Walnut Grove Water Storage Co. and developed plans for hydraulic mining, a technique that had been used extensively during the California gold rush. Purchasing a large financial stake, New York millionaire Henry Van Beuren later became the company’s president and public face, but the Bates brothers remained heavily involved behind the scenes.

Work on the Walnut Grove Dam began in 1886, and problems plagued construction from the start. The owners hired and fired a succession of chief engineers ...

Hydraulic mining began in the 1850s, when miners in California’s Sierra Nevada devised a way to wash gold-bearing sediment from stream banks using something akin to an enormous fire hose. Using pressure created by impounding water behind a dam, miners discharged as much as 185,000 cubic feet of water per hour under high pressure, moving up to 100,000 tons of dirt a day into sluice boxes or holding ponds.

“I am at a loss to illustrate the tremendous force with which the water is projected from the pipes,” a reporter for the San Francisco Daily Alta wrote. “The miners assert that they can throw a stream four hundred feet into the air. ... Those streams directed upon an ordinary wooden building would speedily unroof and demolish it.”

Using the technique, the North Bloomfield Mining and Gravel Co. carved out a canyon more than a mile long and 600 feet deep at Malakoff Diggins in California’s Nevada County. By one writer’s estimate, the tailings raised the Yuba River bed 50 feet. “This was once, I am told by old residents, a swift and clear mountain torrent,” he wrote. “It once contained trout, but now I imagine a catfish would die in it.”

Downstream, a foot of silt a year flowed into San Francisco Bay, and Sacramento river channels had to close to steamboat traffic. In the winter of 1861-62, flooding resulting from hydraulic mining covered the southern Sacramento Valley with a lake of toxic sludge, called slickens, bringing the consequences of the practice literally to the steps of the state Capitol. Thirteen years later, slickens buried the entire town of Marysville at the confluence of the Yuba and Feather rivers, killing residents and destroying thousands of acres of farmland.

Hydraulic mining proved so devastating that by 1884, the California Supreme Court had granted an injunction against the practice. Yet an Arizona newspaper wrote glowingly of the Walnut Grove project: “As gold exists almost everywhere in the country that will be served by these waterworks, the only question is as to its abundance. If the gravel contains sufficient gold, hundreds of men will, for many years, be kept at work washing it out. Small gardens and farms will be made in what is now a semi-desert, and domestic animals will live and thrive where, for want of water, they cannot now go.”

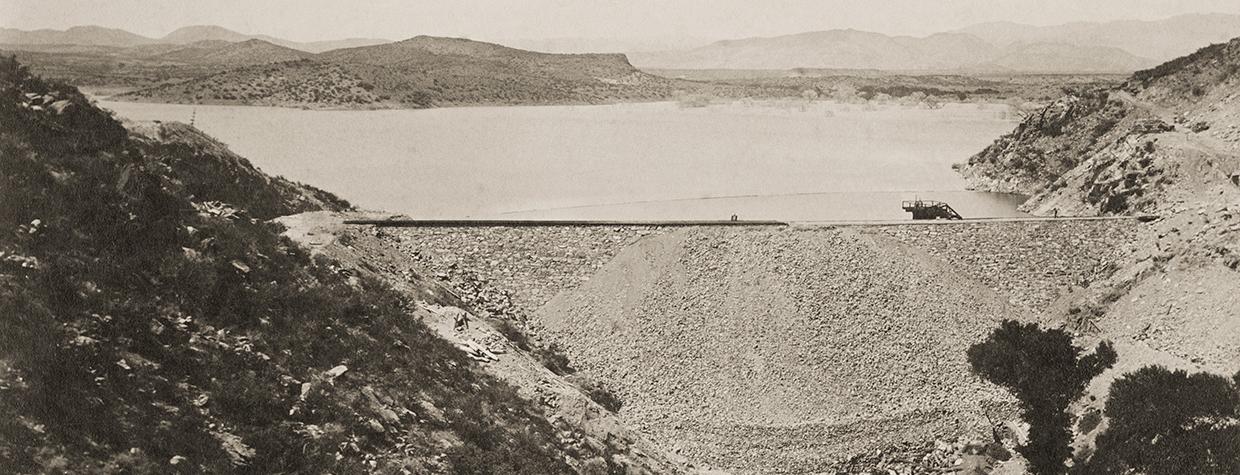

Work on the Walnut Grove Dam began in 1886, and problems plagued construction from the start. The owners hired and fired a succession of chief engineers, some of whom lacked any engineering experience at all. The second, E.N. Robinson, was a well-qualified engineer from San Francisco. He found both the work to that point and the original design so lacking that he abandoned it and started over, re-engineering the dam to include an ample spillway to prevent floodwaters from overtopping the structure in a flood.

But Robinson was fired within a few months and replaced by Walter Bates, a third Bates brother. Still in his 20s, Bates had worked only as a salesman. He immediately scrapped Robinson’s plans for the dam’s spillway, constructing a smaller, less costly one.

In 1887, the company hired Luther Wagoner, another respected San Francisco engineer, but not to oversee the dam’s construction. Instead, the Bates brothers employed him to design and oversee construction of a 20-mile flume leading to the gold-bearing placers. Wagoner later said he thought the dam construction “full of blunders” and had warned company officers the spillway would be inadequate in a major flood.

U.S. Army veteran Alexander Brodie served as the project’s final chief engineer beginning in 1889, after the 110-foot-high dam was completed, and oversaw construction of a lower diversion dam downstream.

In February 1890, work was underway to enlarge the spillway, which had been damaged by runoff, when a torrential rainstorm pummeled the state. In the Phoenix area, the Salt River rose 17 feet in 15 hours, washing out a section of railroad bridge. In Prescott, Granite Creek reached its highest recorded level in Territorial history, flooding Gurley Street and washing away an icehouse.

Two prospectors camped near the Walnut Grove Dam recalled that on Friday, February 21, the water was rising 18 inches an hour. Meanwhile, the dam’s superintendent, Thomas Brown, had 15 men blasting the spillway to enlarge it. Fearing it wouldn’t be enough, he gave the best horse in camp to a blacksmith named Dan Burke and ordered him to ride downstream to warn residents.

But Burke never made it. A second rider, William Akard, found him at the Cameron Ranch, “so drunk he could scarcely walk across the floor.” Akard didn’t make it to the lower dam in time to warn the 125 men camped there, either.

In the early hours of Saturday, February 22, Brown watched by the light of a lantern as water overtopped the dam. Thomas Hunt, who kept watch with him, later recalled that he and the superintendent stood on a bluff as water 3 feet deep poured over the dam. A steel cable broke with a ball of fire and what sounded like an explosion. In the next instant, the ground shook as if moved by an earthquake as the entire structure gave way with a deafening noise. Nearly a million tons of rock moved down the river in a solid mass, wiping out everything in its path and scouring the canyon walls smooth.

A witness said the 100-foot-high wall of water glowed spectrally “with a million phosphorescent eyes” as it moved down the canyon through the moonless night. Within two hours, the 1,100-acre reservoir had emptied, leaving boats stranded in the mud. It took only about half an hour for the flood to reach the lower dam, exploding it into pieces. The flood carried away tents and buildings, pulled up massive cottonwood trees by their roots and snapped them “like pipestems,” and stripped the canyon to bedrock.

The wall of water was still 40 feet high by the time it hit Wickenburg. There, it destroyed farms and ranches as it swept through. The river continued to flood homes as far away as Buckeye and Hassayampa, where it emptied into the already-swollen Gila River.

As the sun rose on Saturday, bodies, many mutilated beyond recognition, littered the shoreline. One man could be identified only by his belt. Dead horses and human bodies were lodged in trees, with debris and fish 80 feet above the river. “The loss of life is … beyond the power of the pen to describe,” one reporter wrote.

Most of those who died had been camped at the lower dam. Survivors there built makeshift coffins from what debris they could find and floated them down the river to where the bodies lay. When their material ran out, they buried the remaining victims in the sand, covering the graves with rocks. No one knows for sure how many died, but skeletons believed to be flood victims turned up months and even years later.

Maricopa County Sheriff William Gray headed north from Phoenix with a rescue party, while Yavapai County Sheriff William Owen “Buckey” O’Neill rode south from Prescott. They found survivors starving and naked or clad in grain sacks or their underclothes. One man was rescued from the top of a tree. Another was saved by his long hair, which had tangled in a bush.

“All the men speak in most enthusiastic terms of the untiring and self-sacrificing work being done by Sheriff O’Neill,” a newspaper reported. “They said he was here, there and everywhere, wading in water, floating coffins, and shirking no duty.”

One newspaper estimated the property damage at $3 million to $4 million — the equivalent of $100 million to $130 million today. The editor of the Engineering News blamed the disaster on Van Beuren’s “foolish tinkering” and the misguided belief that anyone could be an engineer. Yet when Van Beuren returned to Prescott in March, he received a hero’s welcome. The Fort Whipple band serenaded Van Beuren at this hotel, and Arizona Chief Justice James Wright applauded the company’s efforts.

Just four days after the flood, the Arizona Weekly Journal-Miner opined, “The destruction of this dam … should by no means be used as an argument against the feasibility and complete practicability of water storage.” It hailed the dam’s builders as “pioneers.”

Van Beuren paid out some $6,000 (about $200,000 today) in claims to contractors and employees, yet despite the quality of construction being roundly condemned by trade publications and most newspapers, a court ruled against a group of 14 flood victims, including pioneer Henry Wickenburg, who collectively sought $93,000 (about $3 million today) for property damage and loss of life. According to some accounts, the victims were ordered to pay the company’s court costs.

Arrested for manslaughter, Burke was released because the law made no provision for his negligence. A newspaper reported that he immediately celebrated his release by “drinking and carousing.” Amid calls for his lynching, he left the area and was never heard from again.

A witness said the 100-foot-high wall of water glowed spectrally “with a million phosphorescent eyes” as it moved down the canyon.

Soon after the dam’s collapse, Van Beuren immediately made plans to rebuild it, and at his deathbed in 1906, his daughter promised to continue those efforts. Her husband took up the cause after she died. But for various reasons, the dam was never rebuilt.

Preserved as a state historic park, California’s Malakoff Diggins remains a moonscape. Arsenic and mercury used in the mining process continue to contaminate the groundwater, soil, rivers and lakes. But the Hassayampa River flows clean and clear through the ranchlands of the Walnut Grove area, and the site of the lower dam is now part of a Bureau of Land Management wilderness area.

In 1986, The Nature Conservancy bought the land that had been Frederick Brill’s farm and cattle ranch and turned it into the Hassayampa River Preserve. It’s now operated by Maricopa County’s Parks and Recreation Department. The river corridor supports a population of native longfin daces, a key indicator of the waterway’s health. It also nourishes a habitat that supports gray and red-shouldered hawks, threatened yellow-billed cuckoos and endangered Southwestern willow flycatchers, as well as lowland leopard frogs, 17 species of bats and 50 species of dragonflies.

And the folly that was the Walnut Grove Dam is seldom thought of — when it’s remembered at all.