When the Yavapai and Tonto Apache tribes agreed in the early 1870s to give up the fight for their homeland and settle on the Rio Verde Reserve, they thought the worst was finally behind them.

As part of their surrender to the U.S. Army, the indigenous people, from two distinct cultures that collectively occupied a traditional homeland of 200,000 square miles, agreed to live on an 800-square-mile reservation along the Verde River. The years of battle against General George Crook and the Army had left the Yavapais and Apaches sick, starving and exhausted. The reservation was much smaller than what they wanted, and the two tribes did not like being lumped together, but they were ready to call the Rio Verde home.

“My great-uncle Billy Smith told me when I was a little kid that after my people came to surrender, they talked to the Army general,” says Vincent E. Randall, an Apache elder and the longtime Apache culture director for the Yavapai-Apache Nation. “Billy’s father told him that the general had pointed to a large rock next to the river and made a promise. He said: ‘As long as that rock is standing, this land will be yours forever.’ ”

The Yavapais had traditionally lived west of the Verde River, hunting and gathering over a massive expanse extending all the way to modern-day Wickenburg. The Tonto Apaches had lived on land east of the Verde, along drainages such as Fossil Creek and West Clear Creek. They called themselves Dilzhe’e, which means “the hunters.” And even though the Yavapais and Apaches were enemies, they attempted to make the best of their situation on the new reservation, which occupied some of the most fertile land in Arizona.

Following the instructions of the federal government to take up farming, the tribes built more than 5 miles of irrigation ditches along the Verde for growing crops. Their harvests of vegetables, melons and hay were so plentiful that they could feed themselves and sell the surplus to soldiers at nearby Fort Verde. Unlike other Arizona tribal lands, where indigenous people were dependent on meager government rations, the Yavapais and Apaches were largely self-sufficient. But according to Randall, this success raised the ire of European immigrants. White farmers and ranchers moving into the Verde Valley wanted the fertile land for themselves. And a group of Southern Arizona businessmen called the “Tucson Ring,” which sold overpriced tribal rations to the federal government, didn’t like losing money on the Rio Verde’s self-sufficiency. To increase profits, the Tucson Ring petitioned the federal government to move the Yavapais and Apaches to less fertile ground.

In 1875, not long after the tribes had been told the Rio Verde land would be theirs forever, President Ulysses S. Grant signed an order breaking the promise. The Rio Verde Reserve was abolished, and Grant instructed the Army to relocate the tribes to San Carlos Apache Tribe land in Southeastern Arizona.

Randall’s great-great-uncle told his son Billy: “Well, I guess that rock next to the river must have somehow disappeared.”

Randall describes the San Carlos Reservation during the late 1800s as a “concentration camp” where the Yavapais and unrelated Apache tribes were forced together and made to live on poor-quality rations supplied by the Tucson Ring. “The move was very devastating,” Randall says. “According to Apache philosophy, the creator puts people and animals in specific places. We call this Shi Keeyaa, which means ‘homeland’; it is where we belong. The Verde Valley is our home.”

But in February 1875, the federal government wasn’t worried about how the forced relocation would affect the indigenous people of the Verde Valley. The goal was simply to move the approximately 1,500 Yavapais and Tonto Apaches living on the Rio Verde as cheaply as possible. Crook and William Corbusier, an Army doctor serving the reservation, proposed that wagons be used to transport the elderly, pregnant women and children. They also said the most humane route would be to go south on an established wagon road toward Phoenix, where it would be much warmer for a winter crossing. But Edwin Dudley, the Indian commissioner in charge of Arizona at the time, would have none of it.

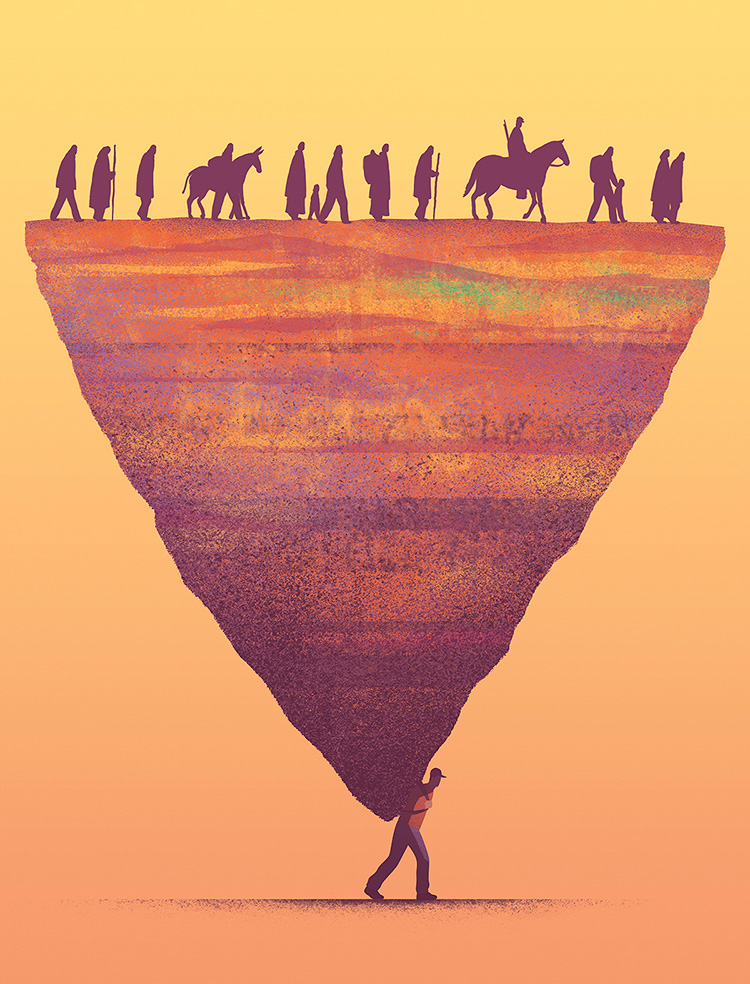

Some four decades after American Indians in the eastern United States were driven from their homeland on the Trail of Tears, and 11 years after the Navajos were forced to endure the Long Walk, the Yavapais and Tonto Apaches marched to San Carlos.

“They are Indians,” Dudley said, according to Corbusier’s journals. “Let the beggars walk.”

Some four decades after American Indians in the eastern United States were driven from their homeland on the Trail of Tears, and 11 years after the Navajos were forced to endure the Long Walk, the Yavapais and Tonto Apaches marched to San Carlos. Under the orders of Dudley, they were sent on a direct but dangerous route: 180 miles over snow-covered mountains and raging rivers. Nighttime temperatures were often below freezing. The tribes were accompanied by 15 armed cavalry and an anguished Corbusier, who tried to offer help where he could.

Corbusier recalled the treacherous march in his memoir, Verde to San Carlos: “The band was composed of all ages, from babes in arms to old men; the sick and the lame, and pregnant women — all with burdens, on foot and discouraged. All of these with inadequate clothing — worn-out shoes or moccasins or none at all — and snow and rain and floods at every turn. It was a cruel, cruel undertaking.”

An estimated 115 Yavapais and Apaches died along the way. The Army would not allow the tribes to perform traditional burial ceremonies, so the bodies of loved ones were left behind in the snow.

In December 2016, about 140 years after the forced march to San Carlos, Jordan Lewis was literally walking in the footsteps of his ancestors.

Lewis and several other tribal members were part of a digital mapping project to document the cross-country route that the Yavapai-Apache Nation calls the Exodus Trail. They purposely went in winter to do the trek under the same harsh conditions that their ancestors experienced. The trek had not been repeated since the forced march ended in 1875, so Army journals and tribal elders were consulted on what would be the most historically correct route from modern-day Clarkdale to the site called Old San Carlos.

Lewis was a recent high school graduate working in the tribe’s culture office. He was overweight and out of shape, and he’d never been backpacking before. But his supervisors recruited him to participate in the epic walk.

“It was the hardest thing I had ever done,” recalls Lewis, 24, who said sometimes, when he had to hike long stretches, his pack weighed 65 pounds. “But I was glad I got to go. I wanted to see what our ancestors went through for us.”

With a Yavapai mother and an Apache father, Lewis is committed to learning about the history of his people. He proudly introduces himself in the traditional American Indian way, first in the Yavapai language and then in Apache.

“When I was growing up, my grandmothers had already died, and so I never heard stories about the march,” Lewis says. “And in public school, I found it shocking that there were no accurate teachings about history or what actually happened to our people in the Verde Valley.” Lewis thought that by helping map the Exodus Trail, he could bring that forgotten history back to his tribe.

The first leg of the trek, between Clarkdale and Camp Verde, was nothing like what the Yavapais and Apaches experienced in 1875. Lewis and his partners walked down paved highways, through shopping centers, past restaurants and around housing developments. But as they headed southeast, into the Mazatzal Wilderness, the terrain became remote and rugged, virtually unchanged from 140 years before.

As Lewis trudged up 5,800-foot Hackberry Mountain and across Hardscrabble Mesa, he thought of his ancestors and how different his life is today. “They had such a strong mindset,” he says. “They never knew when they were going to stop. They could only rest when the cavalry let them. But I got to walk without anyone looking over my shoulder. I am free. I have shoes.”

In his memoir, Corbusier describes one particularly strong and determined tribal member: “An old man placed his aged and decrepit wife in [a “V”-shaped burden basket] with her feet hanging out, and carried her on his back. … Over the roughest country, through thick brush and rocks, day after day, he struggled along with his precious burden — uncomplaining.”

It was near Fossil Springs — not even halfway through the 180-mile march — that the cavalry-led expedition ran out of food. The provisions for such a large group were inadequate and disappeared quickly, and cattle driven alongside the American Indians had all been slaughtered or wandered off. Hunger made the marchers desperate. When a soldier shot a deer for food, the Yavapais and Apaches fought over the meat. Four tribal members were killed before the soldiers broke up the battle.

Lewis and his partners hiked an average of 10 to 15 miles per day to cover a 200-mile route. Lewis got blisters on his feet, and his tennis shoes were always covered in cactus spines. Many days, it snowed or rained, and the hikers often woke up to discover frost on their tents. On two different occasions when the group was hiking on U.S. Forest Service land, ranchers accused them of trespassing on private property. And once, they had to hide from two men who were harassing them and attempting to chase them on ATVs. When the hikers reached Theodore Roosevelt Lake, which they crossed by boat, members of the Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation came and sang prayer songs to ensure a safe remainder of the journey.

After 16 days of walking, Lewis and his crew made it to Old San Carlos, next to the often-dry Gila River. “I thought about how this land would have looked to my people when they first arrived,” Lewis says. “In the Verde Valley, it is lush with trees to lie under. But San Carlos is dry and sparse. And our people were forced to live there for 27 years.”

An entire generation born on San Carlos land had no direct memory of their true home in the Verde Valley. But the desire to go back to Shi Keeyaa never waned.

An entire generation passed before the Yavapais and Tonto Apaches were allowed to leave the San Carlos Reservation. Many of the tribal members who came from Rio Verde died of old age, influenza or other diseases. And an entire generation born on San Carlos land had no direct memory of their true home in the Verde Valley. But the desire to go back to Shi Keeyaa never waned.

“From 1875 through the early 1900s, we were constantly asking about going home,” says Maurice Crandall, a Yavapai-Apache tribal member who holds a doctorate in history and teaches Native American studies at Dartmouth College. “I have read the Bureau of Indian Affairs records from San Carlos. The petitions to return started immediately and continued year after year. Every Indian agent and officer who was there reported groups of my people asking, ‘When can we go home?’ ”

By the turn of the 20th century, the Apache Wars were over and the federal government was no longer interested in funding the large concentration of American Indians held against their will at San Carlos. Around 1902, Yavapai and Tonto Apache tribal members discovered they could simply wander off the reservation without repercussions. They trickled out in family groups and slowly made their way back toward the Verde Valley, often working at mines and dam construction projects along the way. But when the people arrived in their traditional homeland, European-American immigrants had taken over their previous dwelling sites and springs. “We lived as squatters in camps around the mines,” Crandall says. “We could not get back our ancestral lands.”

In 1910, the federal government purchased 18 acres at the old Army barracks at Camp Verde to give the Yavapais and Tonto Apaches a place to live. And in 1934, under the auspices of the Indian Reorganization Act, the Yavapai-Apache Nation was created — along with federally recognized tribal land in Middle Verde and Camp Verde. Today, the Yavapai-Apache Nation’s land encompasses more than 2,000 acres in five communities — Camp Verde, Middle Verde, Clarkdale, Rimrock and Tunlii — and the tribe has grown to more than 2,000 members.

The Yavapai-Apache Nation saw its economic conditions improve when its Cliff Castle Casino opened in 1995. Gaming revenues have allowed the Yavapais and Tonto Apaches to become self-sufficient again, supporting programs for the elderly and youths, along with a cultural center that teaches members traditional practices, such as basket weaving, and lessons in the Yavapai and Apache languages.

A towering bronze statue sits at the entrance to the center. It depicts the elderly man who carried his wife in a burden basket on the march to San Carlos. And every year, at the end of February, the Yavapai-Apache Nation celebrates Exodus Return Day, which commemorates the tribe’s return to its homeland from San Carlos. But the trauma of the march, and of the violence that preceded the exile, lingers for many tribal members.

“The results of historical trauma affect the lifespan of our people,” says Randall, the Apache culture director. “It is sad that the elders are all gone. They should be around right now in their 80s and 90s, but alcoholism killed them off.”

However, Randall points to the statue as a symbol of his people’s resiliency and capacity to rise above trauma. “We can survive hardships and pain and still have the heart and desire to live and love someone enough to carry them 180 miles,” he says.

When Lewis hiked the Exodus Trail, he says, he learned a lot about resiliency — not only of his ancestors, but also in himself. The trek made him more connected to the land and determined to educate fellow tribal members about their traditional culture and connection to their home.

As a reminder, Lewis periodically rereads a journal he kept during the trek. One of his favorite entries was recorded at Theodore Roosevelt Lake, when he was camped next to a pond that was bustling with ducks. He wrote: “Definition of strength: Having the power of physical and emotional strength to overcome within yourself what seems unbearable.”