If anyone ever died of a broken heart, it was Gunnar Widforss.

The Swedish artist, dubbed “The Painter of National Parks” for his watercolors of Zion, Yosemite and Yellowstone, loved the Grand Canyon most of all. During his first visit to the Canyon, he wrote, “I have never seen anything that can approach this in majestic beauty,” and by the time he traveled to St. Louis for a November 1934 exhibition of 52 of his works, Widforss had been working at the Canyon for 11 years and living at the South Rim for eight.

The show was a success: Widforss sold two paintings, and the museum board considered purchasing four more watercolors. A St. Louis Post-Dispatch art critic described Widforss’ purple and rose hues as “bewitching,” adding, “To get those flame-and-mist tones, Mr. Widforss must have dipped his brush in magic.”

But something was wrong. Because when Widforss went for a checkup in St. Louis, the doctor diagnosed him with a heart problem so severe that the artist was advised to immediately move to a lower elevation from the 7,000-foot South Rim.

Alone, Widforss slowly worked his way 1,500 miles back to Arizona, driving south into Little Rock, then along U.S. Route 80 and through Dallas and El Paso. He wrote his Canyon friends that he was coming home, if only for a few hours, to pack up paintings and play one final game of poker. Widforss was a below-average card player and even worse with money — so bad that he took payment for his paintings in installments to maintain a regular income.

He had turned 55 barely a month earlier, was just 5-foot-4 and had been described by one art critic as “a wholesome and altogether likable little man.” His friends called him Weedy. He spoke with a high, squeaky voice, and his ruddy, round face was made even rounder by the small, circular wire glasses he wore. A puckish smile came courtesy of the extensive bridgework Widforss had bartered for a portrait he’d painted of a Brooklyn dentist’s wife. He loved women, movies and dancing, too, but he never married, fearing a relationship would interfere with his work.

Widforss stopped in Phoenix, then stayed at Prescott’s Hassayampa Inn before reaching the South Rim on November 30, about a week after leaving St. Louis. He spoke with friends at Hopi House and stopped at El Tovar before driving off in his car, a Ford Deluxe Tudor sedan he’d purchased after selling a large watercolor for $700. Sadly, heading toward Bright Angel Lodge, Widforss veered off the road and struck a piñon pine. He’d died instantly of a massive heart attack.

It was a sudden end for a man who’d traveled the world searching for beauty, painting thousands of works and earning a reputation as the greatest of all Grand Canyon artists. Even if most people don’t know who he is.

Gunnar Widforss proves it’s possible to be immortalized alongside the gods of antiquity and virtually forgotten at the same time.

Grand Canyon place names skew toward the mythic, literary and divine. There are Norse gods (Wotans Throne and Freya Castle), Roman deities (Juno and Jupiter temples), the Egyptian (Osiris Temple and the Tower of Ra) and hints of the Hindu (Vishnu Temple and Krishna Shrine), as well as an Arthurian assortment straight out of Camelot (Merlin Abyss, Guinevere Castle and Lancelot Point).

Widforss is one of only three artists for whom Canyon landmarks are named. Moran Point honors English landscape painter Thomas Moran, who briefly joined John Wesley Powell’s 1873 expedition and produced the epic Chasm of the Colorado, which hung in the U.S. Capitol for 75 years. Millet Point memorializes Francis Davis Millet, an artist with no apparent Canyon ties who died on the Titanic.

For Widforss, there’s Widforss Point. It’s accessed via the Widforss Trail, which is 5 miles long and edges the abyss for about half that distance as it follows the North Rim geological feature known as The Transept. The trail drops into drainages and meanders through forests of ponderosa pines, white firs, blue and Englemann spruce, and aspens. Widforss would be pleased — he adored trees, once writing of aspens, “They fascinate me much more than the Canyon.”

He also would love the point that now bears his name. At an elevation of 7,811 feet, the limestone knob of Widforss Point takes in major Grand Canyon landmarks, including Zoroaster, Buddha and Brahma temples, as it looks beyond the South Rim to the San Francisco Peaks, 60 miles away. To call it the definitive Grand Canyon view would be a stretch: There’s too much competition and no defining the undefinable. But the point is a fitting tribute to Widforss, assuming hikers bother to read the trailhead placard that explains who he was.

For Alan Petersen, curator of fine art at the Museum of Northern Arizona, preserving Widforss’ legacy has become a mission. After moving to the Canyon in 1976, he bought the 1969 book Gunnar Widforss: Painter of the Grand Canyon for his mother, an artist. The book was written by noted photographer and river runner Bill Belknap and his wife, Frances Spencer Belknap, after the couple, fearing Widforss’ story would be lost forever, interviewed the dwindling cadre of the artist’s Canyon friends.

Petersen read the book before sending it off for Mother’s Day. “I immediately fell in love with Widforss’ work,” he says. “He has remained one of my favorite artists ever since.”

In 2005, Petersen went to work at the museum, which had an association with Widforss dating to the 1920s, as well as the largest collection of his paintings. Officials there decided to present an exhibition, but Petersen soon realized little, if any, scholarly research about Widforss existed. The painter popped up in surveys of Western art, meriting a few paragraphs and reproductions, but nothing beyond that.

Then, on a frigid Flagstaff day a few months after the exhibition’s 2009 opening, Petersen received a call from someone also named Gunnar Widforss — who turned out to be a great-nephew of the painter. He owned around 30 Widforss works that he needed help selling. As a curator, that put Petersen in an ethical gray area, but he agreed to at least assess the paintings’ market value. “I felt bad for Gunnar, the artist,” he recalls. “Because there was nothing happening for him.”

While examining auction records, Petersen says, he had an epiphany: “Nobody has looked up Gunnar’s market record. The next logical conclusion was, I have to do this. Meaning, create a catalogue of his work. So, in a nanosecond, my life pretty much changed. The journey began, and it has been an incredible treasure hunt.”

The resulting Gunnar Widforss Catalogue Raisonné Project is the most authoritative source on the painter, filled with photos and biographical details as well as images of nearly 1,300 Widforss works, from childhood drawings and unfinished works to masterpieces.

Petersen wasn’t the only one around that time to rediscover Widforss. Fredrik Sjöberg, an acclaimed Swedish writer, critic and naturalist, spotted Widforss’ 1917 Pine Tree at Roskar at an auction, only to get shut out of the bidding. But Sjöberg turned his newfound Widforss obsession into an extended essay published in his 2017 book The Art of Flight. He compiled lost details of the painter’s life while recounting his own Southwestern road trip from Las Vegas to the Canyon in a rented lime-green Ford Mustang. “Every man’s life is a labyrinth,” he wrote. “Once you have found the way in, you can spend countless amounts of time there.”

Sjöberg, too, was baffled by the paucity of details about Widforss and his obscurity in his native country. The artist was educated at a technical institute, not the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts. That training helped him earn a living painting whatever he sometimes needed to paint — signs, backdrops, fences, reproductions of masterpieces — but hardly gave him the pedigree of a serious painter.

Petersen says Widforss came out of an earlier Swedish tradition that emphasized light and clarity, which put him out of step with the modernism of the time. “There were even some people who said he wasn’t an artist at all,” Sjöberg wrote. And one critic dismissed Widforss by saying he “functions as a sort of human camera.”

Widforss may have lacked an academic pedigree, but art was in his DNA. His mother was a talented amateur painter, and he descended from several generations of artists, including an ancestor who in the 1800s became the first woman to design coins and medals for the Royal Swedish Mint. “I would say he had some prodigious innate skill,” Petersen says. And, as unassuming as he may have been, he never lacked ambition: He aspired to be an artist — a serious one — and pursued his career with discipline and determination.

Widforss first came to the United States around 1905, living in Florida and Brooklyn. Before that, he’d worked as a decorative painter in St. Petersburg, Russia, and later, he traveled extensively in Europe. By 1912, King Gustav V of Sweden owned several Widforss works — as did Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand, whose assassination triggered World War I.

Widforss lived along the French Riviera, then spent much of the war in Sweden and Scandinavia. After that, he journeyed to Tunisia, developing an affection for desert landscapes and light, before sailing for New York in 1920, bound for Japan. But he never got past California. At Yosemite National Park in 1923, National Park Service Director Stephen T. Mather encouraged Widforss to focus on the parks. A show featuring 72 Widforss watercolors opened in 1924 at Washington’s National Gallery of Art, and the gallery’s director, W.H. Holmes, declared, “These are the finest things of their kind that have come out of the West. [Widforss] is possibly the greatest watercolorist in America today.”

When Widforss moved to the Canyon, Petersen says, he faced an artistic challenge akin to “walking into the next bigger room.” It typically takes multiple attempts to get to the essence of a new subject, he adds. “But Gunnar didn’t start out with an isolated butte or temple in the middle of the Canyon. He didn’t start with a view down a side canyon. His very first painting was a big, classic North Rim panorama. He went for it, the whole enchilada. And it’s spot on.”

No mere overlook artist, Widforss frequently hiked down to Phantom Ranch, carrying his brushes and watercolors in a worn leather knapsack. Dressed more for a stroll around Stockholm, he donned breeches, knee-high boots and a fedora, sometimes even sporting a necktie.

Legendary Canyon photographer and adventurer Emery Kolb recalled that Widforss, while painting the masterwork Plateau Point, trekked down to the point and back for 10 consecutive days — a round-trip of 13 miles, with a climb of more than 3,000 feet. His pack-a-day smoking habit undoubtedly added to the challenge. (He enjoyed his whiskey, too.)

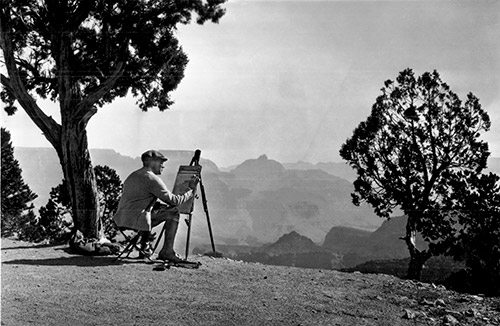

Committed to his plein air technique, Widforss rarely painted indoors. “It’s so much better to sit out in the middle of a scene,” he told a friend, and he not only captured the monumental geology but also mastered the evanescent, sometimes nearly invisible haze that gives the Canyon its depth.

Petersen says Widforss could work on a painting for only an hour or two each day before the light changed and he switched to another subject. His skills as a draftsman meant he could create a highly detailed drawing, then spend 10 to 12 days completing a large painting.

“He developed his technical ability to the very highest level, so he could get to the heart of the matter very quickly,” Petersen says. “And despite the complexity of the subject, the paintings themselves are not that complex. There are really only four or five layers of paint. He didn’t labor over them and knew how to get to where he was going.”

Widforss never did solve his money woes. He lived for a time in a fold-up trailer along the rim and worked out an arrangement with the Fred Harvey company to trade paintings for a bed in an employee dorm and meals at Bright Angel Lodge. Sometimes he reluctantly churned out watercolors in a few sittings, then sold them unframed for $30. Petersen estimates Widforss painted 4,500 works over his lifetime.

Self-critical as he was, Widforss never lost faith in himself. “If I’m allowed to live for many more years and if times get better,” he wrote, “I’m sure that one day I’ll become famous as a painter of the Grand Canyon, and perhaps I’ll earn some real money. That’s what ought to happen.”

Fate would steal those years, but not before Widforss found his place in Canyon history. He revealed the intimacy within the immensity, evoking that moment when you gaze with wonder at the Canyon while anticipating what awaits around the next bend. If Moran commands the viewer to behold his God’s-eye vision, a Widforss painting is like going out on a hike with Weedy himself.

In the Belknap book, Hopi artist Fred Kabotie, painter of the murals at Desert View Watchtower, distilled Widforss’ essence: “When you look at one of his paintings, you always know what kind of day it was, just what the weather was like. You hear the aspen leaves and smell the pine needles. It makes you feel like you’re right there.”

For more information about the Gunnar Widforss Catalogue Raisonné Project, visit gunnarwidforss.org.